Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

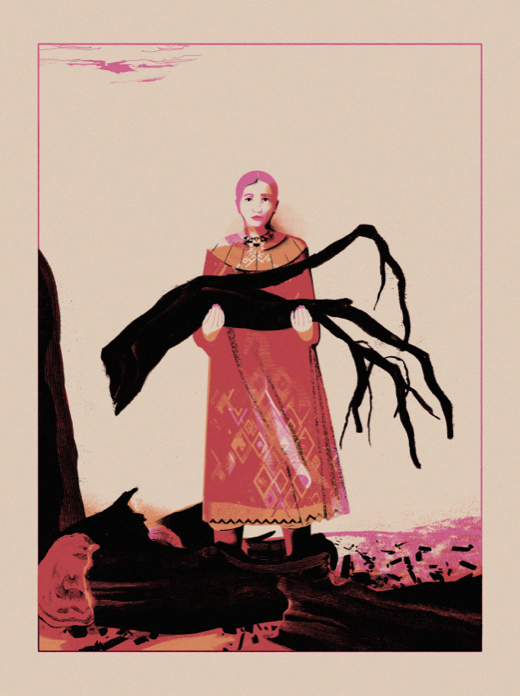

Azadeh Elmizadeh is a Toronto-based visual artist who works between painting and collage, striving to capture the dynamic process of becoming. She holds an MFA from the University of Guelph and a BFA from Ontario College of Art & Design and Tehran University.

As her daughter learns to speak, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder meditates on how to listen for a language of mothering that is in service to all of life’s beings.

My first fragment of memory is of my mother. We are standing together in golden, waving grass. There is the sense that the sun is setting behind us, because what I see in the memory is not our physical bodies but our shadows, cast before us, wavering as the grass bends and circles in the wind. My mother and I are holding hands, and in our silhouettes there is no distinction between where she ends and I begin. And the grass of the rolling plains grows and reaches through our conjoined image.

I’m not sure that this memory is of a “real” moment. Probably something like this did happen, whether or not my impression of it is true. When I was one and two years old, we lived on a Nature Conservancy preserve: tens of thousands of acres along the Niobrara River in north-central Nebraska—a landscape of Sandhills prairie, bur oaks, and bison; a landscape of restoration situated within a wider, fraught history of colonization and displacement.

Real or not, this image has been with me for a very long time. It has had different things to say to me at different points in my life. We all have these: encounters or experiences that not only stay with us, but take on more meaning and power over time, thus becoming fixed points around which parts of us will always turn. This memory of my mother is, in its way, a hierophany: a manifestation of the sacred. It is an axis—perhaps an axis mundi—one way of organizing my relationship to sacred space.

Since my own daughter’s arrival into the world, this particular manifestation has returned to ask me a question: What is it to be a mother in a time of ecological collapse?

It’s an early morning at the beginning of April, the day still dark—darker still with a steady rain falling. I turn on the lamp and open the window in my office. It’s in the mid-forties, but I love the sound of rain on the plexiglass roof that covers our porch, slanting between my office window and the backyard, where the grass is waking from its long slumber. I welcome the rush of cold, damp air and the gentle, pattering hush of water that smells and sings of spring. In the other room, my husband and daughter are listening to John Denver’s Rocky Mountain High, a record that we recently recovered from my father-in-law’s attic. We’ve listened to it over and over. In his “Season Suite,” on side two, Denver sings these lines that I haven’t been able to get out of my head for weeks:

And oh, I love the life within me

I feel a part of everything I see

And oh, I love the life around me

a part of everything is here in me

Maybe it seems a bit frivolous, given everything that is going on in 2021, to have been so fixated on this piece of Americana from a 1972 country album. But in this time of spreading disease, with a new baby and our loved ones kept at a painful distance, I think I’ve needed Denver’s unapologetic and joyful affirmation of our connection with something greater than ourselves. Or perhaps these lyrics are pointing me toward this inner-outer aspect of motherhood that I’m struggling to understand: How the boundaries of my individual body have blurred. How Aspen’s gestation began a mysterious process of osmosis that I can’t fully comprehend. How her arrival expanded my understanding of ritual as something ancient, bodily, animal, as, together, we underwent the initiation of birth.

My desire to untangle my felt sense of interconnection from my entrenched mental concept of individualism has continued into motherhood, albeit in a variety of new ways. At six months old, I muse to myself, Aspen is the only one in our small family who truly understands Denver’s lyrics. In this time of ecological unraveling and cultural disorientation, the present, trusting attentiveness of this child intuits that which I only experience glimpses of, before I then think about it, my critical mind taking things into the realm of abstract thought. I always have to stop and remind—or re-body—myself; my senses have to chase this intuition through a fog of conditioning and concepts. Aspen is this intuition. Every morning she wakes to greet a world that greets her back. She takes it all in with generous attention and curiosity. She is startled, she is awed, she is frightened, she is patient. There is a fluidity to the boundaries of her being. She is a willing pupil of a world that, in every moment, rises anew to meet her.

In my mid-thirties, I have come up in a Western culture that has taught me to look back on my life with the reverse perspective: the world does not continually rise anew; it is already there, almost a foregone conclusion, with the inevitable, linear drive of human history behind it. “Nature,” Western culture tells me again and again, is separate from “me” and operates apart from my enlightened, rational, human reality. I am the doer; the Earth is acted upon.

The A:shiwi (Zuni) elder and farmer Jim Enote tells the story of how his great-grandparents awoke every morning before dawn to say a prayer to help the sun rise. He expresses regret that the science-based mindset of our time makes it extraordinarily difficult to be a twenty-first-century person and still hold such beliefs. It’s not that Jim is anti-science. It’s that he mourns the loss of this infused intuiting of reciprocity.

The widespread loss of the belief that the world needs our prayers and attention—and might not rise to greet us without them—is a tolling bell for the species and ecosystems that have vanished or been pushed to the brink. I’m remembering Jim’s story as I hear Aspen babbling away in the other room. I mourn how violently Western culture has stomped out this intuition … But then I am struck: Aspen’s world is coming into being. My god, I realize, she has not yet been taught to forget.

I attend a workshop in which cultural ecologist David Abram speaks about animism as the “spontaneous experience of how the world reveals itself to us.” He says: “If you allow that everything has vitality and agency, then you notice that everything is expressive.” Everything, he says, has meaningful speech.

The sound of this morning’s rain enters Aspen’s consciousness. What does she hear? What is the sound of rain without the word for rain? I don’t know. I hear this sound, and while I want to stay present, I find myself led from the word “rain” to fretting about a winter that was too warm and a spring that came too early. As Charles Foster says: “When I think I’ve described a wood, I’m really describing the creaking architecture of my own mind.”1

In a Western capitalist culture that feels so irreversibly conditioned to its own internal logic, its own seemingly unstoppable momentum, its own ego, its own monied tongue—all of which have wrapped their threads around me, too—I can hardly believe that thirty feet away from me in the other room, beneath the rain that runs down the roof, is a human being who is currently free of this conditioning. I wonder how, as a mother, I can nurture this freedom.

We read books to Aspen and sing to her. I speak to her in my halting, intermediate French, hoping she might have some sense of another (human) language, even if my pronunciation is rusty. But listening to the rain this morning, I feel a little tug of resistance in giving her these human words at all.

Aspen has started making what seem to be her first intentional attempts at language. All day she says, “na-na-na-na … ba-ba-ba,” which Andrew and I of course interpret as “ma-ma” and “da-da.” But mostly she makes these sounds without any particular attention to either one of us. She spontaneously expresses herself as she explores, discovers. The sounds she makes are mostly in conversation with something other than us. She, like all infants, is a little animist in an animate world.

On mornings like this, I remind myself to be silent. I remind myself to give her ample space to listen to a much wider, deeper, more complex language than that which emerges from my own trained tongue. It is within this wide space of silence that I can witness the way my daughter meets Rain. It is in stillness that I can ask, What realities are possible at this meeting place of the world and our perception of it?

And I suppose that what is possible is this: that the meeting place itself might blur, and then disappear.

In a moment, I’ll close my computer and turn off the light, and I’ll bring her out to the porch. I’ll try to pull myself out of my mind. We’ll stand under the plexiglass roof and listen to the birth of spring—as dynamic as the drops that are falling in ever new patterns from the gray sky like little prayers. Together, we’ll witness a world coming into being.

So many of the stories we hear today are about a world falling out of being. Falling away. Falling from grace. Twenty-three more species declared extinct. Floods and fires. Vanishing topsoil. Climate refugees. These are stories of the mass-scale unraveling that is taking place as we pull more and more threads out of the Earth’s great pattern to weave something that is entirely of our own making, an image that reflects only ourselves. We continue this hungry work even as the stunted design we are creating spells our own demise.

In Linda Hogan’s book Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World, she travels to the Boundary Waters, where a group of ecologists is working to study and help restore a slowly recovering population of wolves. Linda is there with some visitors who have come to tour the region, with the hope of glimpsing a wolf in its native habitat. But the first glimpse of a wolf that they get is in the form of a carcass, pulled out of the back of a pickup truck. Many of these visitors are neither ecologists nor what one might classify as conservationists. Some hunt and trap wolves, others are afraid of them. But Linda is struck by the fact that every one of them cannot resist the urge to reach out and stroke the pelt of this animal, to “touch a lost piece of the wild earth.” To connect with something that we have severed from ourselves.

On the last night of their tour, the group is out in the woods and it has turned dark. They still have not seen a living wolf. And then a long howl breaks through the moonlight. A hush falls over them as they seek the source of the sound. They realize it’s coming from one of the men in their party. He howls again “in a language he only pretends to know,” and the group of people surrounding him—as well as the woods, and the world beyond—answer with silence. Linda writes: “We wait. We are waiting for the wolves to answer. We want a healing, I think, a cure for anguish, a remedy that will heal the wound between us and the world that contains our broken histories.”

Is it possible, I wonder, to build a bridge between these broken histories and an uncertain, deeply troubled future?

Here are the paradoxes that I hold as a new mother: I believe that the world can simultaneously fall out of being and come into being. I believe that the cracks and chasms of our fragmenting civilization will widen and deepen in my lifetime and certainly in our daughter’s; and I believe that bringing new life into a world in collapse is still a morally sound choice (and that the decision not to bring new life into the world is morally sound, as well). I believe that even our limited languages might lead us—if we continue to listen and reach for knowing—to a truer expression. I don’t believe there is any cure for our anguish that will stop our present downfall; but I do believe there is a cure.

The cure, the healing, is that which will bring us back into a deep, loving, entwined relationship with the living world. And this, I believe, is the work of mothering.

By “mother” I do not mean the noun that refers to females with a uterus and children. I mean everyone—of any gender, any age, any species. I mean people, trees, robins, and rivers. As Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass, “A good mother … [knows] that her work doesn’t end until she creates a home where all of life’s beings can flourish.” I mean “mother” as a verb, and “mothering” as the good work of being in service to “all of life’s beings.”

I don’t pretend to know what the future will look like. But I believe that, more than anything, the apocalypse will need mothers.

What is a mothering orientation and practice in a time of great uncertainty? There is no one answer of course. There are spaces of stillness and silence. There is the annual flood of nutrients that washes over the riverbank and into thirsty wetlands. There is ritual and ceremony. There is the spider who carries her hatchlings on her back. There is listening. There are the Mother Trees that Suzanne Simard studies, who recognize and care not only for their kin, but for “strangers too, and other species, promoting the diversity of the community.” Notably, the Mother Tree, “facing an uncertain future, [passes] her life force straight to her offspring, helping them to prepare for changes ahead.”2

As a writer, I tend to gravitate toward practices of words and stories. This is often where my mind goes when I think of mothering my daughter. Sometimes, when that memory of my mother and I standing in the grass returns to me, I can’t stop thinking about shadows.

A recent article in The New Yorker, “Green Dream,” yanks a knot in my stomach that has been tightening for some time. Is limitless clean energy finally approaching? reads the subtitle. It’s a story about nuclear-fusion energy which promises, among other things, “a carbon-free way to power a household for a year on the fuel of a single glass of water”—if only scientists could at last figure out how to safely unleash this unending source of energy.

I won’t pretend to understand nuclear fusion. Perhaps it could in fact be a “solution at the scale of the problem,” as one aerospace engineer says. (Though I suspect not. This is a telling misunderstanding: that the climate crisis is wholly a problem of science with an as-yet undiscovered scientific solution. But it is our separation from the Earth herself that lies at the heart of our crisis, and thus, in my opinion, the work of healing must primarily be the work of spirit. But these are the gospels of our scientific age: “Clean” alternatives mean we can keep living like we’re currently living. We can keep consuming. We can keep ignoring that separation, that collective lack of center.)

No, what is troubling me is not nuclear fusion, but that word: limitless. What is troubling me is a language that is entrenched in anthropocentrism. These are the shadows that can sometimes paralyze me: shadows that impose, shadows that are dark sides, shadows that block the light, shadows that desire to cast our own image onto the land. As a writer, I see the way that those sorts of shadows often take the form of words. I notice the way that I, too, employ them.

A mothering language is one that strives to bring the world into being through story.

In Myths to Live By, Joseph Campbell writes that it was the Greeks who shifted the center of our collective awe from the greater-than-human world to man himself. Thus drama and myth in Western storytelling came to revolve around the plight of the individual human being, and this became the accepted frame of our myths. David Abram convincingly claims it was the alphabet that broke the animistic bonds that had kept us in constant dialogue with the nonhuman beings around us and instead placed us under an utterly self-referential spell through which we came to express ourselves in ways that only we could understand, thus closing ourselves off from that wider, woven conversation. With the Enlightenment came a parade of thinkers and explorers who parsed the world into its rational parts and used words to document, explain, and justify that parsing. Obviously, a great deal of scientific knowledge is unquestionably valuable, astounding, lifesaving. I certainly depend upon it. But, along the way, our collective knowing forgot that we are beings of, among, and dependent upon a living Earth and oriented itself around human supremacy (leading to, among other things, white supremacy and patriarchy). Language perpetuates such consciousnesses.

“The English language can wield our collective shadow like a weapon,” I write. And that feels like a very satisfying thought. The critical part of my mind likes to sink my teeth into words like “limitless” and shake them around, asserting that such notions of hubris will only result in our self-destruction. But this is only another violence. This is my own shadow at work. It’s a frame of the problem that is built by the very forgetting and separation that plague our collective consciousness.

Many have thought and written about this and there is no need to go into great detail here. But the questions I’m concerned with are: How and where within this structure do we locate a language of mothering? Can mothering utilize Western languages toward another end? Are there different ways to think about shadows? Different dimensions?

And this is when the image of my mother and I in the grass returns to me again.

With a profound lightness, with a shushing wind, it asks me to look closer. Look again at your shadows there in the grass, it says. So I look.

And here is what I see:

That when my mind is critical, it is prone to forgetting—even resisting—love. Because loving a world that is collapsing can be too painful. But, there in my memory, I see that our shadows have lain down ahead of us, not to shade out the grass, not to make our mark, but to be with the grass, and the grass is dancing through us. There is no pain. There is no imposition. Instead, there is an easy and full love between my mother and me. And I can’t see where my mother ends and I begin and where I end and my daughter begins; and I think this melding must be true, too, for where our shadows end and the grass begins.

And when the word “limitless” comes to me this time, it alights softly and waits.

Aspen, too, continues to teach me about ways of using language that open us to that which is beyond language. She turned one in early September. Her first human word is Hi!, which she says, every time, with that exclamation point. (Her other first word was a dog-word: woh woh! in response to dogs barking). “Hi!” she says to the willow tree as she pets its bark and shakes its leaves. “Hi!” she says to the neighbor’s sheep, bleating in their pasture. “Hi!” to ants, crows, stuffed animals, fruit flies, and our Portland Seadogs novelty bobblehead. “Hi!” she says, occasionally, even to people. Everyone thinks this is very cute—which, of course, it is. As her mother, I can confidently say that just about everything she does is cute. But other people often think it’s cute because, in her endearingly naive way, she doesn’t yet know that, in our culture, we don’t say “hi” like this to anything that’s not a person.

But her father and I think that her greetings are, in fact, radical. This wasn’t something we taught her. And it’s something we’ve seen plenty of other children do. Their innate intuition ascribes personhood—thou, not it—to every being they encounter. Aspen does not discriminate. She delights in the inherent being of all creatures. What a simple act that carries so much awareness and recognition! For me, that this inclination is still present in the open minds and imaginations of children, even twenty-first-century Western ones, holds so much more promise and potential for our salvation as a species than the theories of nuclear scientists who are working on fusion.

“Hi!” is now a family practice—together we greet crab apples, blackberries, the osprey that dives into the churning sea, the quiet shell on the beach, each other, the dewy morning, and the brisk evening.

There is a lot of talk today about the ways in which our modern, Western stories are not working. Certainly not the stories of capitalism and progress. Not even the stories of environmentalism. I agree. But I stumble a bit when there is talk of the new stories we need. I mostly agree with this, too, but I wonder how to tell stories—new or old—from a rooted, grounded place.

Where are these stories when you come from such a malnourished culture? We have a great deal to learn from our Indigenous teachers: whose voices we ought to center. But even with our best intentions, we also ought to be very cautious of plucking Indigenous stories from their own cultural ecosystems. There is a difference between learning and transplanting. I don’t know that we can simply pull stories from others’ rooted traditions and fold them into our own.

We might turn to our own wisdom and religious traditions. After a few years of studying comparative religion, it was abundantly clear to me that our diverse faith traditions each carry stories, symbols, and rituals that, as Joseph Campbell says, speak to us “of matters fundamental to ourselves, enduring essential principles about which it would be good for us to know; about which, in fact it will be necessary for us to know if our conscious minds are to be kept in touch with our own most secret, motivating depths”:3 i.e., the makings of myth. Of course, the expression of that wisdom—and the way in which myth works on our conscious and subconscious minds—is influenced by the present-day culture in which it is situated. But part of the power of ancient traditions is that they speak to something archetypal and evergreen within the human experience and can be drawn upon again and again. I have seen many recent examples of people doing the work of healing our separation from the Earth, specifically through the myth, symbols, and rituals of their religious traditions: Buddhist monks ordaining trees in Cambodia to protect them from logging; my dear friend Steve Blackmer’s Church of the Woods, where the eucharist is offered to people, ferns, and black bears alike; the Kanaka Maoli in Hawai‘i protesting development on the sacred mountain of Mauna Kea, the firstborn child of Wākea and Papa in the Hawai‘ian creation chant; examples abound.

But again, these symbols and rituals can be difficult to fully access if we are not of these traditions.

This is, I think, when we can turn to place itself: the places that have shaped and molded us. The places that we are in deep relationship with. The places that are, or can become, our axis mundi, our sacred centers.

A mothering language is one that strives to bring the world into being through story. It reaches for a space in our collective imagination where all of life’s beings find their home. This means that in addition to listening for the human stories that root our traditions, and in addition to listening to the stories that come through the innate knowing of our children, we must also seek out and tell the stories of the land itself. As creatures born of this Earth, we must tell the stories of the landscapes that have shaped and held us. As mothers, we can practice listening to the voice of the land and allow ourselves to be vessels that share that voice with others. If we are to make a home for all of life’s beings, both in our actions and in our stories, then we must listen not only for our human stories, but for stories of land and place. Where does the story of the land intersect our own histories?

These stories will always be deeply imperfect as they are translated through human language. We will fret about how they are prone to our projections and our biases, our egos and our limited minds. But I hope we will not allow these worries to silence us. Telling these stories through a language of mothering can stretch us toward something greater.

Let us end, then, with one such story from this mother:

Once, there was a river.

She came into being, found her form, sixty thousand years ago, fed by Great Plains springs and groundwater. She wended and braided. She carried silt and sand. She flowed west to east, carving gently into the land. Through this weaving of water, River came to be.

Who was River as she found her shape so many millennia ago? She was, for one, a home for many different waters. Meltwater. Rainwater. Stream water. Aquifer water. These waters came from many different places: Sky. Stream. Dune. And the dark, damp of the Belowground.

But the true majesty of River was this: as she welcomed more and more water, and as that water flowed faster and faster, River became a time weaver.

Picture in your mind: River’s waters were always flowing, flowing. Sometimes as steady and wide as a soft line of cloud. Sometimes tumbling, cascading, and splashing over stone on her way. As these different dances of water were moving over the land, they picked up and carried with them, bit by bit, little pieces of the land. They took sediment and sandstone, chalk and ash, shell and bone. As they did, as the water carved its valley, River etched her way through ancient layers of the past and thus reached further and further back into time: Through the sand dunes that were laid down and shaped by wind. Into the sand and ash of the Ash Hollow formation. Next into the soft, off-white sandstone of the Valentine formation, where the water uncovered the bones of saber-toothed deer and giant tortoise. Then through the siltstone of the Rosebud formation, until the waters reached all the way down to Pierre Shale and its millions-year-old fossils of uncanny beasts, like the ammonite and the thick-bodied plesiosaur. All of these layers of time were folded into the current and carried away. And thus, River wove the past into the present.

But here is something even more extraordinary: as River’s waters surfaced the past and pulled it into the current, the stage was simultaneously set for the future.

The exposed siltstone of the Rosebud became home to a bur oak savannah that was able to grow because of spring seeps that emerged from the south canyon wall of River’s valley. Ponderosa pines took root on the particular shape of the bluffs that River carved into the Valentine formation. Mixed grass prairie spread across the top of the Ash Hollow.

And when the ponderosa pine had taken root, and the bluestem had gone to seed season after season, and the leaves of the bur oak unfurled their emerald green in yet another spring, then, one day, a mother and her daughter came to the river.

In the evening when the sun was setting, they stood, hand in hand, admiring River and her shining water, their shadows stretching before them, swaying in the grass.

River’s waters flowed past them, on and on across the land, in her snaking, rolling dance, until she dispersed into the open mouth of a delta, and at last vanished into the wide mystery of the sea.

- Charles Foster, “Against Nature Writing,” Emergence Magazine, July 21, 2021.

- Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (New York: Knopf, 2021).

- Joseph Campbell, Myths to Live By (New York: Viking, 1972), 24.