Terry Tempest Williams is the author of numerous books, including the classic in environmental literature, Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place; Finding Beauty in a Broken World; The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks; and most recently, Erosion: Essays of Undoing. She is a recipient of a Lannan Literary Fellowship, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, and is currently Writer in Residence at the Harvard Divinity School. She divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Castle Valley, Utah.

Terry Tempest Williams searches for what is revealed when worlds unravel, tracing the entangled nature of undoing and becoming.

Unravel un·rav·el | \ ˌənˈravəl \

verb

gerund or present participle: unraveling

1. undo (twisted, knitted, or woven threads) Similar: untangle disentangle straighten out separate out unsnarl unknot unwind untwist undo untie unkink unjumble 2. (of an intricate process, system, or arrangement) disintegrate or be destroyed Similar: fall apart come apart (at the seams) fail collapse go wrong 3. investigate and solve or explain (something complicated or puzzling) Similar: solve resolve work out clear up puzzle out find an answer to get to the bottom of explain elucidate fathom decipher decode crack penetrate untangle unfold settle reveal clarify sort out make head or tail of figure out suss (out)

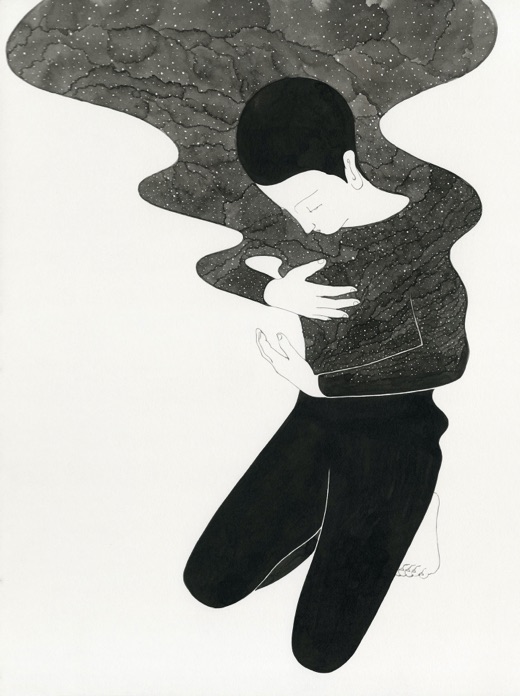

I am unraveling. I am unraveling like a rattlesnake in the desert tightly coiled, my tail issuing a warning I cannot yet decipher. My mind is unraveling as I move to free my thoughts from being held captive for too long in such a tensely wound space. For months, I have been in a defensive stance visible only to surrounding ghosts. Fear brought me here. Uncertainty brought me here. Two hundred and fifty thousand dead from the coronavirus brought me here. My capacity to strike, from one emotion to the next, frightens me. After isolating myself in a landscape of arid beauty for the past nine months during a global pandemic, why do I find myself in the process of unraveling now? What is waiting and wanting to come forth?

When I don’t know what something means, I do three things: consult a dictionary; ask someone I respect and listen; go for a walk.

The dictionary gave me definitions, but what caught my attention was the word “reveal” in the list of synonyms. To unravel is to reveal what has been hidden. And when I asked my father (now eighty-seven years old and weathering the pandemic at home with his partner and a borrowed dog named Sparky) what he thought it meant to “unravel,” he simply said, “I’m too bored to think about it.”

I understand.

An hour later, Brooke and I went for a walk. We found a small, unexpected pioneer cemetery, adorned with plastic red and blue roses, on a bluff overlooking the Dolores River. We stopped to watch a great blue heron fish the shallows. The long-legged bird was not unraveling; she was paying attention, focused on her task. Within minutes, she speared a trout, most likely a rainbow. We watched her slowly, deliberately walk back to the mudflats, toss her head back, releasing the fish into the air, and on its way down gulp the trout whole. The narrow body of the trout, now a bulge, was moving down her neck in a series of muscular swallows. The heron stood still for some time along the riverbank, then waded back into the depths of her perfect concentration.

What interested me in this particular moment was how the heron could live her life, as her species was meant to live, with an integrity of purpose in place—even as the ecosystem to which she belongs is unraveling around her. Climate change is affecting the flow of the Colorado River, with incoming tributaries like the Dolores waning. We are now in what climate scientists are calling “a megadrought.” Moab’s average annual rainfall is 10 inches. In 2020, we have received 4.9 inches, less than half the norm. Monitoring the health of the Dolores River, the nonprofit group Conservation Colorado gave the Dolores River a grade of D− in terms of its water quality. Why? Dams and reservoirs disrupt the natural flows and displace sediments, deeply altering the character of the river. Abandoned mines and uranium tailings continue to leach into the headwaters, carrying on a toxic history familiar to the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Increased fossil fuel development, including fracked gas, is affecting water tables and aquifers, all contributing to its failing grade.

Could we read the health of the great blue heron fishing along the Dolores River through this poisonous narrative now alive in her bloodstream? Like us, each species large and small—feathered, furred, or finned—carries the larger story of planetary health in their cells. The difference between our species and other species is that we are responsible for much of the demise of all the others.

As life on the planet is unraveling, in ways seen and unseen, we are also unraveling the natural consequences that these larger narratives of unconscious behavior are inflicting on populations, both human and wild. For example, the heinous, illegal wildlife trafficking infiltrating “wet markets” (where fresh meat, fish, and produce are sold) from Asia to Africa and across the globe is responsible for 75 percent of zoonotic viruses. COVID-19, the disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, is a zoonotic disease. That means it came from an animal or animals. SARS-CoV-2 is not the first novel coronavirus to infect humans—it’s the seventh.

A report from the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD) found “that the United States imported almost 23 million whole animals, parts, samples and products made from bats, primates and rodents over a recent five-year period. These animals harbor 75 percent of known zoonotic viruses—pathogens that spread from animals to people.”

We are Earth unraveling and reforming creation.

Wildlife markets in China—where animals are “kept in cramped cages for purchase and slaughter”—are believed to be the source of the global pandemic we now find ourselves in. The CBD goes on to say that “many researchers believe it originated from a bat, a scaly mammal called a pangolin (globally the most heavily trafficked mammal), or potentially both. The virus may have spilled over to humans from an unknown animal. Or it may have evolved after infecting people.”

We are unraveling in inexplicable ways given how tightly and mysteriously the world is woven together. Pull one strand and all the strands are disrupted, threatening the integrity of the overall pattern.

Along with dictionaries, scientists, and the land itself, I consult the Dead. I hear my grandmother telling me to focus on “the golden thread” that shows us “the through line” that weaves the world back together again. Where might this golden thread be found now?

In March, early in the novel coronavirus pandemic, a global prayer was held at a designated time on a Sunday morning for the Earth and all its inhabitants. Like so many collective rituals, this reached me on the wind by word of mouth.

I walked outside and faced Round Mountain, an ancient volcano plug in the southern end of the valley where we live. I held my grandmother’s “hand stone”—an egg-shaped, polished amethyst—in my right hand as I had seen her do repeatedly. It was her talisman, which she bequeathed to me in her will. She told me it calmed her heart and opened it. I closed my eyes in prayer—believing in the power and connectivity of people gathered together in the name of health and peace on the planet. My mind was quiet, receptive.

In time, I began to feel a heat rising in me from the ground up. To quell my fears and skepticism, I kept my attention focused on how the warmth was settling in my body. In my mind’s eye, I saw a flame coming toward me from the center of Round Mountain, gaining in heat and size and intensity, until it entered my heart, becoming “a burning core of care”—those were the words that came to me as this force burned with a ferocity of intent that I have never known. My grandmother’s hand stone was hot, almost too hot to hold. Opening my eyes, I opened my hand. The stone was shattered inside, with dozens of fracture lines appearing that had not been there before. It didn’t make sense. My eye focused on a particularly large and complex fracture that occurred at the intersection where the deepest purple merged with the brightest, clearest part of the crystal. Within that broken angle, it appeared brown, burnt. I lifted the crystal up toward the light, and therein, I saw a flame.

I have no explanation for this other than to say that what was burning in me burned through the gemstone in my hand, shattering it. The energy I felt rising from the Earth through the soles of my feet and from Round Mountain itself reached directly into my heart with the radiance of a million prayers circulating around the planet and in that moment created a fire in me of inexhaustible light.

In my desire to understand my own unraveling in this global pandemic, I could not have imagined that it would be my grandmother’s golden thread that would lead me to the source of both my undoing and becoming: isolation and engagement. The golden thread became the gilded sunlight woven into the wings of the great blue heron fishing along the banks of the Dolores River. This same shimmering thread exposed the facts that deciphered the toxic residues from abandoned mines and uranium tailings which are poisoning our rivers, poisoning us, and killing creatures. In a similar way, it cinched the illegal wildlife trade that taunted wet markets with “bush meat,” ripe with tainted blood, a spillover causing a global virus infecting us all, threatening what we have taken for granted: Life.

This golden strand reveals what binds awe and terror together, as it travels through shadow and light—illuminating the loose threads waiting to be picked up by each of us so we can mend, repair, and restore what has come apart. We can reweave the world anew, not from the places of fear and doubt, but from the intimate spaces of belonging we must retrieve for ourselves. We are Earth unraveling and reforming creation. We are meant to engage not isolate. These are difficult days. What causes us to recoil, strike, and retreat is also what allows us to reach out from the anxiety of unknowing and dare to trust what is to come—a reassembling of our humanity.

There is something deeper than hope. Between the hours of darkness and dawn, the voices of our ancestors are amplified in the dreamtime—warning us of our awakening wisdom—a blessing to behold and a burden to enact.