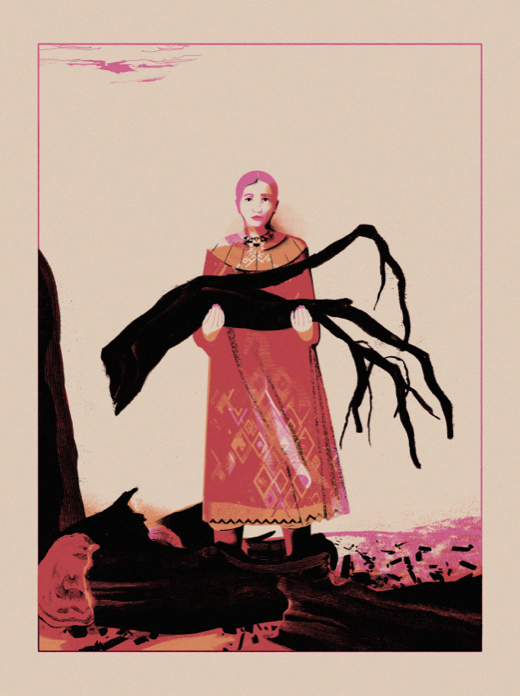

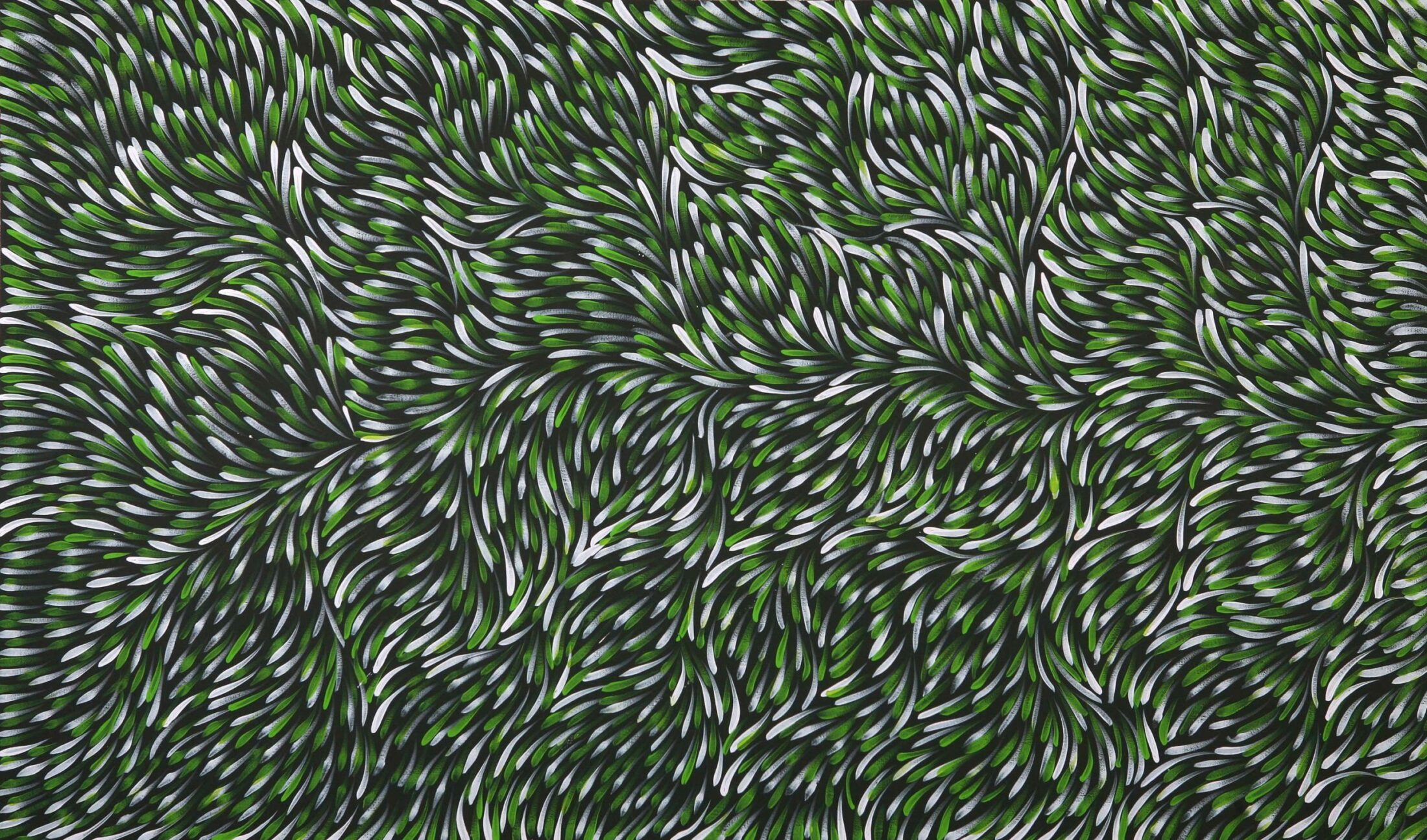

Bush Medicine Dreaming by Gloria Petyarre

© Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd

The Inward Migration in Apocalyptic Times

Alexis Wright is a member of the Waanyi people from the highlands of the southern Gulf of Carpentaria in Australia. She is the author of the novels The Swan Book and Carpentaria, winner of the Miles Franklin Award, Australia’s most prestigious literary prize. Wright has published three works of nonfiction: Take Power, Grog War, and Tracker, a collective memoir of Aboriginal leader Tracker Tilmouth and winner of the Stella Prize. Her most recent book is Praiseworthy. In 2017 she was named the Boisbouvier Chair in Australian Literature at the University of Melbourne.

Gloria Petyarre is an Aboriginal artist who creates nature-inspired paintings using delicate brush strokes and elements of her Aboriginal culture. She is the custodian of several Dreaming stories, including the Pencil Yam, Bean, Emu, and Mountain Desert Lizard. Gloria is the recipient of the prestigious Wynne Prize and has been selected as a finalist in the Telstra Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award in the Northern Territory. Her works have been featured in the Robert Holmes à Court Collection, The National Gallery of Australia, and the Museum of Victoria. She lives in Utopia, an Aboriginal homeland located in the north of Australia.

As the world falters, threatening native ecosystems and Indigenous lifeways, acclaimed Australian Aboriginal author Alexis Wright turns inward to the dwelling place of ancestral story. From here, she considers how her ancient culture has responded to ongoing destruction—and how to bear witness to the creation of a post-apocalyptic world.

A buddhist monk and Zen poet named Huineng once wrote a gatha, or poem, over a thousand years ago. The poem, “There Was No Tree to the Bodhi,” was essentially about how the purity of enlightenment would not be corrupted by the dust particles of life. The four-line poem ends by asking, “Where then was the dust?”1

The essential truths of my people, held within our land and within the knowledge of country, have endured great storms of dust—cultural oppression, drought, fires. As I was thinking about this at the turn of the century, two questions arose: How far would we as Aboriginal people go to survive? What is the future of the planet?

Seeking answers to these questions, I ended up writing The Swan Book, a novel that imagines an apocalyptic future and shows how Aboriginal people are tied through globalization to the inequalities and suffering experienced by millions of others across the planet. I could not foresee the global pandemic emergency, nor how it would link all of humanity in a global tragedy and an urgent worldwide fight for our survival, but I was drawn to write about our struggle in the worst conditions.

The book is also about swans. I felt a great sense of comfort in being able to lose myself in the world of swans while working on this book. I did this in a kind of obsessive way, through contemplating how their universally felt beauty shone through the ages in poetry and epic stories. I felt the joy and wonder of their existence by imagining being in their presence during times of extreme drought, then rain, and in different parts of the world, while also feeling the sadness of how their fate has become tied to ours amid the growing emergency of man-made climate change.

The swan offers an image of something incorruptible amid the dust. While in their presence, metaphorically speaking, I tried to capture the beauty dancing in us still, even in the worst of times, and I began imagining stories like this:

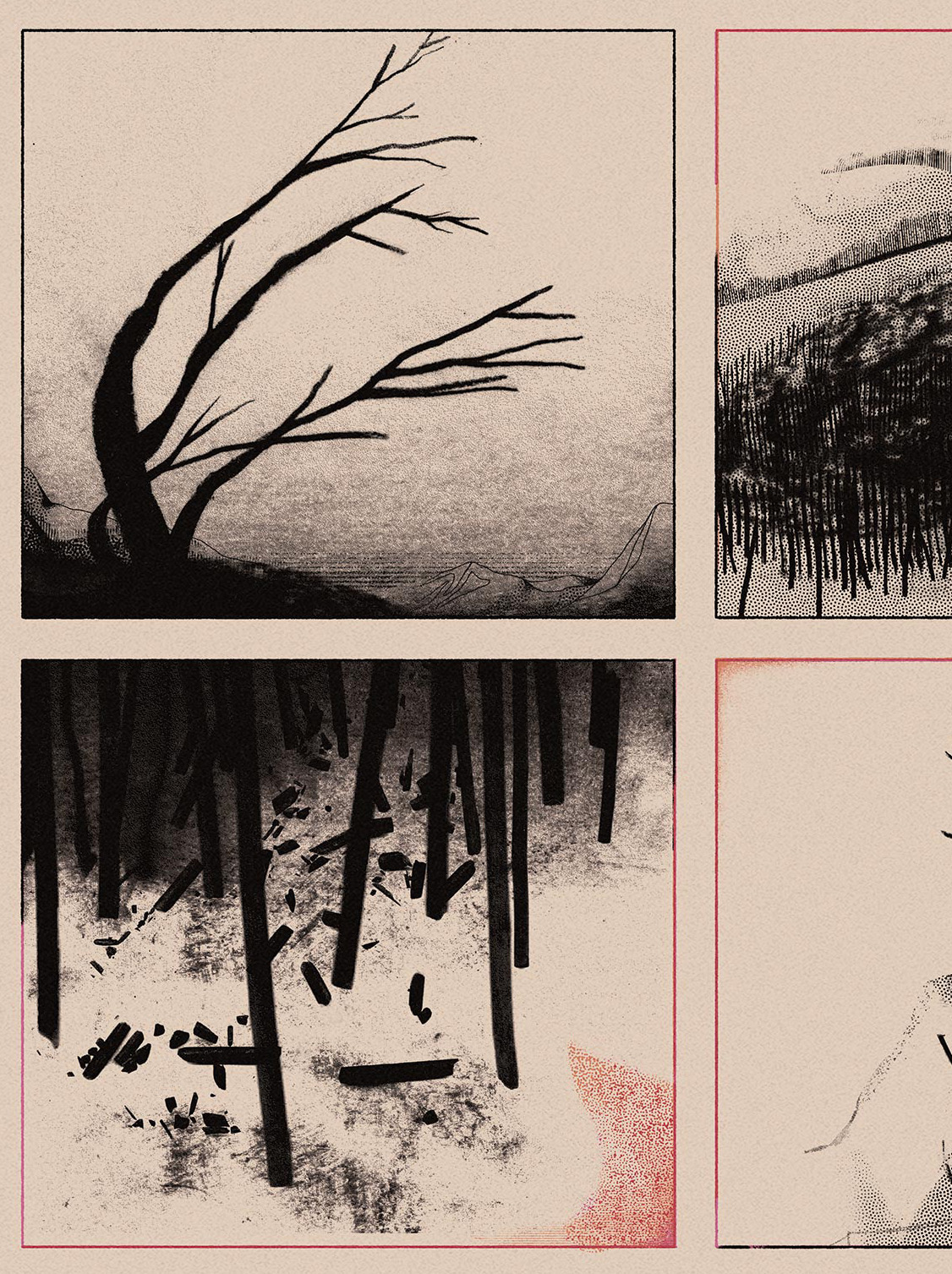

Its journey took the black swan over the place where hungry warrki dingoes, foxes and dara kurrijbi buju wild dogs had dug out shelters away from the dust, and lay in overcrowded burrows in the soil; and in the grasses, up in the rooftops, in the forests of dead trees, all the fine and fancy birds that had once lived in stories of marsh country, migrating swallows and plains-dancing brolgas, were busy shelving the passing years into a lacy webbed labyrinth of mud-caked stickling nests brimmed by knickknacks, and waves of flimsy old plastic threads dancing the wind’s crazy dance with their faded partners of silvery-white lolly cellophane, that crowded the shores of the overused swamp.

When The Swan Book was published in 2013, the Australian literary critic Geordie Williamson described the book as a curse poem, comparing it to Ibis, a poem that Ovid composed in exile—a period during which he considered himself to be buried alive and created poetry that reeked of sadness, isolation, pride, self-pity, and anger. Williamson felt that my novel, like Ibis, emerges from the experience of exile: “in this case, the physical displacement and inward migration of Indigenous Australians since European arrival in 1788.”

This inward migration can be described as being locked in a prison of the mind. It can also be described as retreating to the dwelling place of stories: a return to country, going home to where the stories of our culture are kept in the mind—for the mind that knows how to read country. The inward migration is most often a solitary journey, a turning away from the bombarding speed of reality hitting your very sense of being and destroying your soul. Returning to the place of country held in the mind is a way of figuring out how to deal with the powerlessness we sometimes feel from having to continually hold back the end-of-the-world times and confront ongoing realities. It’s where we go to slowly pick things apart, to reimagine our world in new ways, and sometimes we come out the other side with a map of how to make some sense of our world.

An inward migration can also be thought of as closing one’s country, closing the door, sealing off the home place in the mind from others. It is through an inward gaze that we go back to country in thoughts and in dreams. We return to talk with the spirits about how the deep feelings of culture can be thought through, cared about, and compared with our knowledge of the world. It is where we examine truth, and it is through our soul-searching that art and beauty can grow, regenerate, deepen the connections—just as country renews and fulfills its own stories. “Catch the beauty before it fades away,” said Mandawuy Yunupingu, the beloved singer of the band Yothu Yindi from the Yolngu homelands near Yirrkala in Arnhem Land. You can see the power of this beauty, of being in the precise place of vision, running through all of our art and stories, in both traditional and contemporary forms.

This inward place is where we work with our own thoughts—our own sovereignty of mind, our own sovereignty of imagination—and where we keep our own knowledge safe. This is where we fashion, and refashion, and imagine the stories we want told, where we catch the essence of a story before it drifts away, or before it is overrun by the power of those other stories, created by the score in this country to distract our thinking. In the inward place, we can speak the truth more easily, and often with humor, because of the ease we feel being in the family home of traditional country. This is also where we flourish by making new stories: bringing new sagas of the “all times” into our world and dealing with the stories of consolation, redemption, and reckoning.

It is through an inward gaze that we go back to country in thoughts and in dreams.

At the beginning of this new century, Australian governments were waging a vicious narrative war against the dignity and rights of our people. The result of our long battle to achieve a self-determined future during this time was disastrous, and the ground that our remote communities lost then has not been regained.

As the backward policy direction called the Intervention was being implemented against the will of Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, I kept asking myself whether we had the strength to continue fighting. We were already severely affected in our ability to survive in terms of culture, tradition, laws, our soul, and spirit. How could we endure if our children continued to be faced with such threats? This led to further questions. I started to wonder what the very last Aboriginal person standing in this country would be like. What kind of people were we becoming? I felt the full weight of this question.

In the Aboriginal world, we know the apocalyptic realities of two and a half centuries of continual invasion, an invasion informed by the Enlightenment project of colonization, which has been driving the major environmental disasters of the Anthropocene and the harmful realities of globalization. As Mozzie Fishman states in my novel Carpentaria: “‘You know who we all hear about all the time now? … International mining company….’ Now even we, any old uneducated buggers, are talking globally.”

In the movement toward progress and modernity, the importance of ancestral knowledge was forgotten. The deliberate severing of this link—humankind’s oldest knowledge, its oldest wisdom—from the so-called modern world was not a good idea when you think of the Anthropocene, now termed omnicide, or our collective suicide.

The Swan Book, which is set in a postapocalyptic world of climate refugees adrift on the sea, was a way of visualizing global politics in the future and what landlessness will mean for greater numbers of people—epitomized in the story of Bella Donna, who is actually not a black or brown person but a white woman from Europe, presently at the top of the human tree in terms of wealth and land security. Through the character Oblivia, an Aboriginal woman, I wanted to imagine how climate politics would affect my local landscape, how it would dig deeper into the lives of Aboriginal people living at the front line of oppression and dispossession. I wanted to imagine where we were heading—considering not only the apocalyptic circumstances stemming from this dispossession, but also how our lives would become far more difficult over the next hundred years—by putting a story to the scientific facts of global warming.

Since I wrote this book, the world has been changing far more dramatically than I could have imagined at that time. Millions of people have died from COVID-19, while the pandemic has exposed vast inequalities at the global and national levels. You need only look at the distribution of vaccines to appreciate the disparity and the threat it poses to humanity. And we no longer have to try to imagine a changing climate, because we can see the major catastrophes of the climate emergency unfolding around us. Our vulnerable and fragile Aboriginal communities are already experiencing greater difficulty surviving on the land and sea of our traditional country. The summers in arid Australian lands are now longer and hotter, and it is becoming much harder for our people to live and thrive in their communities and homelands. What will this mean for our culture? What will it mean for the health of our people? What will it mean for the oldest stories of ancient knowledge in the world today, held safe by the knowledge keepers in the archives of the land?

Through our stories of country, we know how closely related and interconnected we are, not only to each other but to everything else in the continuous cycles of life. We are taught resilience through the stories of regeneration that have ensured the survival of our culture—a culture that has always remained central in our sovereignty of mind. This sense of sovereignty and self-governance is embedded in our spirit and drives our awareness and insistence that all times are important, and no time is resolved.

In the movement toward progress and modernity, the importance of ancestral knowledge was forgotten.

How far will we go to survive? In writing The Swan Book, I answered my question. Of course, we can never truly know the future. Our people continue to say that we have always governed ourselves. Indeed, our resolve has grown stronger. We create new ways of facing our challenges and of telling our story. Some of this renewed strength can now be seen in the thinking and actions of many of our brilliant young people, who lately have been engaged in the global Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

All I know is that we have survived tens of thousands of years on this continent through the strength of our resilience, the strength of our responsibility, and just as importantly, the strength of our desire to live. It may well be proved one day in scientific terms that we have been here for half a million years or more; but whatever the case, it does not matter if we have been here forever. We say we have been here since time immemorial, and the Aboriginal world values this knowledge because we understand that our resilience is intrinsically linked with the stories that tell of the ongoing, regenerative cycles of the world in which we live. In the “Song Cycle of the Moon-Bone” from East Arnhem Land—one of the ancient song cycles of deep, sacred knowledge looked after by the custodians in the traditional land where the stories originated—we can see the regeneration lessons in this small public part of the story:

The old Moon dies to grow new again, to rise up out of the sea.

Up and up soars the Evening Star, hanging there in the sky.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ………

The Evening Star is going down, the Lotus Flower on its stalk…

Going down among all those western clans…2

I can only believe that we will survive until the end of time, just as we have since time immemorial. Tracker—my collective memoir of Tracker Tilmouth, the Eastern Arrernte political leader, economist, visionary, and former director of the Central Land Council in Central Australia—tells a story about the power of being alive. Tracker called the future the “vision splendid.” His vision was to secure the future of our culture by building a highly sophisticated, multilinked, independent Aboriginal economy based on traditional principles of economics. All of Tracker’s visionary ideas, and there are plenty, were drawn from the enormous architecture of Aboriginal economies that he had built in his mind. He saw possibility everywhere and worked hard at it. He would often say “dare to dream” to the great number of Aboriginal people who came to him for guidance. Tracker had learned from the powerful red ochre law men of the Western Desert of Central Australia when he was a young man. I once asked him what they taught him, and he said it was perspective: “I learnt that you have got to put everything into perspective.” He said they never changed, “so why should the country change?”

Our traditional lands are full of stories: everything has a story, people are tied to stories of all times, and there are numerous important, traditional law stories of ancestral beings, such as Rainbow Serpents. Many of these stories hold deep, sacred knowledge and power and are protected by a strict system of safekeeping that connects people to ancestral stories in various parts of the land and keeps them in kinship with the eternal ancestors. There are numerous epical stories that travel in storylines, some over long distances in the country. One of the longest known continuous songlines extends approximately two thousand kilometers from Port Augusta to the Gulf of Carpentaria. These sacred texts—their stories and songs containing a great depth of knowledge—are honored and preserved through ceremonies and sacred practices which recognize that the ancestral beings are alive in the country, though they may be sleeping, or resting. We say that the land is a living system of harmonious laws for the safekeeping of country and understand that these laws need to stay strong, because once they are broken, so, too, is the harmony, and the ancestral beings will respond by punishing the wrongdoer. There are many stories about what this punishment can look like, including death, sickness, and catastrophic climate events such as cyclones that chase across the country those who need to be punished.

Our ancestors lived through many changes in the country in the ancient past, and in adapting our culture to these changes, they continued to follow the annual cycles of the land, of the seasons, the flow of rivers, of tides, of waves, of currents, of stars, noting that nothing remains static. This understanding of caring for country arose from eons of residing on our traditional lands, and it comes with an acceptance that life goes on but Aboriginal law does not change. Another way of seeing this type of reasoning can be found in Graham Swift’s novel Waterland, where he writes: “There’s this thing called progress. But it doesn’t progress, it doesn’t go anywhere…. It’s progress if you can stop the world slipping away.”

Waanyi country is Rainbow Serpent country, and we say that we are freshwater people. The ancestral stories of Rainbow Serpents tell of the movements, creations, and resting places of these ancestral beings in our country. All of the Lawn Hill Gorge area in Waanyi traditional lands is collectively referred to as Mumbaleeya, or Rainbow Serpent country. One of our important and revered elders once said that no water holes or permanent water bodies had existed in this place before the coming of Boodjamulla (Rainbow Serpent)—who created the deep gorges and keeps them full of water to keep his body wet—and that if he ever leaves, the water holes will dry up. Some of the ancestral beings, such as Rainbow Serpents, are depicted on rock walls in paintings left by our ancestors. We know that some of the most important elders of Waanyi in our memory have said that these paintings were made by our people so that the stories would continually be told and never forgotten.

The catastrophic Australian bushfires that engulfed the traditional country of Aboriginal people early in 2020 burned for months, scorching 12.6 million hectares of land. These horrific fires might have been mitigated, or at least would have been of a lesser ferocity, if Australian authorities had acknowledged and been prepared to use Aboriginal land- and fire-management practices, which were commonplace before colonization. The fires affected millions of people, and the Royal Commission on the bushfires was told during a hearing that the smoke from these fires killed hundreds of people. A billion native animals perished in the fires, and billions of trees were destroyed. In our culture, when someone dies, a smoking ceremony is part of the mourning; but after these fires, there was no national ceremony of mourning for what we lost.

Every September in the Gulf of Carpentaria, across the homelands of the Gangalidda—the northern neighbors of the Waanyi—a natural phenomenon of great significance, the Morning Glory Cloud, travels at the speed of sixty kilometers per hour and rolls across the skies early in the morning, usually when there is dew. My northern countryman Murrandoo Yanner said the Gangalidda believe that the Morning Glory, which can be up to one thousand kilometers long and one to two kilometers wide, was created by Walalu (the Gangalidda name for the Rainbow Serpent). Murrandoo explained: “The general principle we believe is that the spirits of all our dead ancestors are watching over us and travel on that cloud to check out the lower Gulf and go across all their country.” He said that the cloud is a source of energy in this cycle of renewal and regeneration: “It’s turtle season … so it signifies a change in us for our fire practice—we can start burning.” Murrandoo’s ancestral Gangalidda story causes me to wonder about the smoke cloud that came from the 2020 bushfires, a pyre of close relatives and all that was lost on traditional lands. Billions of trees and a billion animals were transformed into 434 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This huge smoking mourning ceremony was still circling the globe four months later: a plume five kilometers high and hundreds of kilometers wide.

Our system of interconnectedness is kept strong through constant and deep respect for the traditional laws associated with ancient story knowledge. We know that many of these ancient stories, passed down through the ages, have deep associations with events that occurred a very long time ago. This helps us to remember the power of the world we live in, that it can change and will go through cycles of renewal, and that new stories of the land will also be composed. This careful system of storykeeping through story practices keeps the stories strong, and it helped our people survive long enough to become the oldest living culture in the world. This is the Aboriginal system of enlightenment.

In The Swan Book, the main character is a troubled young girl named Oblivia who survives the end-times. Even after a long and difficult psychological and physical journey through the apocalyptic, broken world of the novel, Oblivia’s mind retains a template of country. We know that country always calls its people back, because everything in our world tells us that we are connected to our traditional country. I recall an elder from Wadeye in the Northern Territory once explaining that the pull back to one’s traditional country happens because “traditional spirits and magic and totems do not move, even if humans do.”3 The great Irish poet Seamus Heaney explained something about this connection to place while examining the poetry of William Butler Yeats. Heaney explained that country already exists, and it is usually country that creates the mind, which in turn creates the poems; although Yeats, in his later poems, “created a country of the mind.”4

What remains for Oblivia on the other side of apocalypse is her sovereignty of mind, a governance that is premised on the idea that we do not own country, country owns us. There can be no other place for her. When I think about Oblivia now in terms of what the last Aboriginal person standing might be like, I see her as an ancestral traveling hero of extraordinary strength whom you might expect to find in the ancient law stories. It feels as though she is creating a new story track in the climate-changed world of a century from now, or perhaps she is following an old spiritual journey extending thousands of kilometers across the country. It is Oblivia’s resilience that gets her home, back to traditional country. In the end, she has time to sit around in the dust, while nursing the old swan that survives the journey with her, and argue with the spirit of the drought woman, who had caused a century of catastrophic, unprecedented weather. Perhaps they need to argue about the poor state of the swan, to find ways to exist in each other’s company in the future.

This understanding of caring for country arose from eons of residing on our traditional lands.

Although I have learned from writers all over the world, I always think of my writing as having grown out of the everyday stories, dreams, and voices of our people, our communities, our thinking; and these stories are entwined with the ancestral stories that all of our people safeguard in what I call the world’s oldest library—the land, seas, skies, and atmosphere of our traditional home. Writing about the fearlessness of our people, I could see how they were imbued with the strength of the ancestral beings of country. I felt the exceptional powers arising from place, from relationships with traditional lands. It was a comfort and joy to hear characters telling me straight, as some of our wise elders would:

“Did he tell you I take fish from the ocean and make them dance in thin air? I bet he didn’t tell you I am the best fisherman that ever breathed, or that I can talk to the birds for company, and I follow the tracks made by the stars so I never get lost, and sometimes, I go away fishing and never come back until people forget my name?”5

Some of our best wisdom teachers, philosophers, great people of respect and honor, great thinkers from our culture, and master storytellers—descended from those who safeguarded the oldest stories—helped shape my life, and guided and influenced much of my thinking. Among them is my great storytelling grandmother, who gave me the freedom and space to think and to imagine for myself. There were many phenomenal elders who authorized and oversaw many of us in our campaigns for the return of traditional lands; for Aboriginal self-government in Central Australia; for the safeguarding of country from mining, and of sacred sites from desecration; and for building a self-determined and sustainable future for our communities based on traditional economic values. They were all story people who could sit around telling stories all day.

In my work as a writer, I have endlessly thought about the depth of ancient cultural knowledge and how to create a more enriching, self-governing literature that is totally inspired by and built from our own thinking and belongs to this place. When you move into the realm of your own sovereignty of mind by shielding yourself from the kinds of interferences that rob you of the ability to think straight, that sap your spirit, or block you from seeing and making your own judgment, then you are able to govern your own spirit and imagination. This is where a writer must dwell, within the storehouse composed from your own thinking and creativity, where you can develop strengths that will not be defined by how others believe you should think. This is where you can visualize and work with knowledge more imaginatively, and relate to and grow the complexity of all that you have carried within you, which was originally nurtured in your heart, mind, and spirit by your elders, family, and communities.

This inward migration—removing oneself to a place of concentration, imagination, and wondering—is the mind working and sifting through the essence of things; it’s where you begin to try to comprehend the complexity of the endless interconnectedness of place, and what it means to be in place with your homeland, and to visualize faraway places and all of the ideas that arise from curiosity.

The world desperately needs powerful storytellers to help us make sense of the unfathomable events taking place. Where are these future writers? Perhaps they will once again learn from the ancestors—the old ones from all over the world who kept the wisdom with them. We need to call the ancestors back, to bring forth the wisdom of the ages, to help us figure out how we can be saved from ourselves. These future writers need to build, as Rainer Maria Rilke writes, “a temple [for our] hearing” to break the poor shelters “nailed up out of [our] darkest longing.”6 I imagine that we will need ancestors from every part of the world to communicate with those who are perhaps already sitting in solitude, each using some old discarded cardboard box, dragged out of the dump of our consumption-addicted minds, for a writing table—any of those billions of cardboard boxes that have carried the tin cans, the plastics, the technology, the machinery. And while sitting in eternity, the very old ones will be impressing into the minds of these future writers a way of figuring out how to bring life back into the laws of the creative beings in the sand desert and the seas; how to bring life back into the waters, the mountains and skies, the flatlands and plains, back into the bushlands, the forests, the thunder and winds, back into the trees, and the animals.

We will need the bravest of writers, those who will search ceaselessly through the backwaters of their minds, hearts, and souls to find ways to powerfully articulate the new stories, the new sagas, the new imagination, and the new epics of the world, inspired by their doubt, fear, love, longing, and wondering. They will need to see beauty despite the destruction, experience deep sorrow, and find that incorruptible truth amid the growing dust storms.

These visionaries must be capable of seeing that all time is intertwined, important, and unresolved, just as Aboriginal people see time immemorial in our culture. The literary mind of the type of storyteller I am talking about will be borderless and bountiful in the way it creates the world anew each and every time it tells a story; it will work with the unimagined, or unimaginable, to build on what we know, and to rebuild what has already been imagined in the stories we tell of ourselves. By this I mean their stories will tell of all life being of equal value, how the light shines not just on ourselves (and our own personal address) but on the whole.

We—all of us—can do this in the dreamlike state of imagining by being continually curious about the wonder of the world and by shifting and reshaping the positioning and influence of what we have known, or understood—just as our ancestors did.

- Wu Yansheng, The Power of Enlightenment: Chinese Zen Poems, trans. Tony Blishen (Shanghai: Shanghai Press, 2014), 51.

- “Song Cycle of the Moon-Bone,” trans. R. M. Berndt, in The Thunder Mutters: 101 Poems for the Planet, ed. Alice Osward (London: Faber & Faber, 2006), 101–209.

- Chris Johnston paraphrasing Jules Dumoo, in “Going Home: The Great Aboriginal Dream,” The Sydney Morning Herald, July 13, 2013.

- Seamus Heaney, Finders Keepers: Selected Prose 1971–2001 (London: Faber & Faber, 2002), 252.

- Alexis Wright, Carpentaria (Sydney, Australia: Giramondo Publishing, 2006).

- From Rainer Maria Rilke’s The Sonnets to Orpheus, trans. Stephen Mitchell (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985).