Jake Skeets is Black Streak Wood, born for Water’s Edge. He is Diné from Vanderwagen, New Mexico. His debut collection of poetry, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, was a winner of the National Poetry Series and the American Book Award. He won the 2018 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Contest and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His honors include a 2020–2021 Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellowship and the 2023–2024 Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi. His research explores Diné poetics and aesthetics, ecopoetics, Indigenous queer theories, and critical Indigenous feminisms. He currently teaches at the University of Oklahoma.

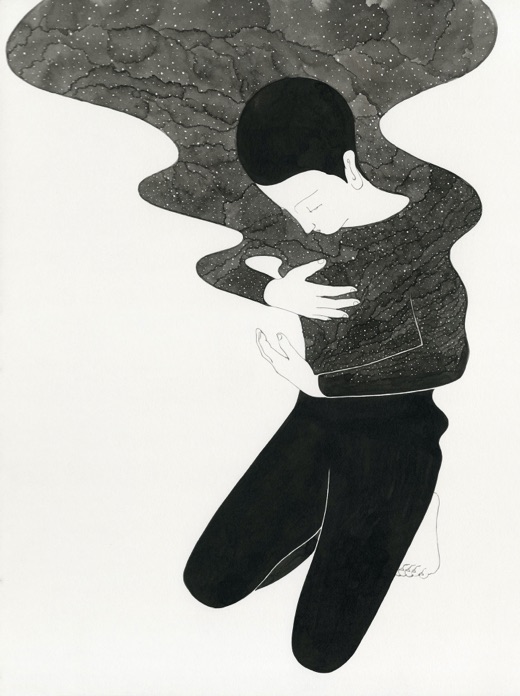

Sydney Cain, aka sage stargate, is a visual artist born and raised in San Francisco, CA. Through the mediums of graphite, powdered metals, lithography, dye, and chalk, their work reflects encounters with unseen realities and considers the intersection of urban renewal and displacement on the psychic, spiritual, emotional, and physical well-being of marginalized communities. Sydney’s work has exhibited at Rena Bransten Gallery, SOMArts, Betti Ono, Ashara Ekundayo Gallery, San Francisco Arts Commission, and the African American Arts and Culture Complex.

As a Native scholar and poet, Jake Skeets considers the necessary interrogation of colonial naming and narratives, and how the Indigenous application of writing as a technology can reshape our world.

One understands the universe through language. English commands my tongue like it commands soldiers to bombs, police to triggers, and poets to poems. But one is unlike the other. My poems are unlike bombs and triggers.

At least, I hope.

Every day, one reconciles the truth that spoken words carry with them the capacity for displacement, death, and erasure. It’s widely believed that words are not violent; that words are somehow two-dimensional, inorganic, flat against a blank piece of paper. However, one’s language carries with it life and energy that move through space and time as if a cosmic force, a matter of physics and not social construction. Is language inherent, organic, a natural force, much like gravity? The answer, I believe, could become the beacon toward a future, a new world, where one is more cognizant of the weight carried every time one speaks, sets words to page, or keys language into the datasphere.

Ron Silliman argues that because one understands the universe through language, one can look to poetry as a site to interrogate the way language constructs our experience of the world. As a poet, I am inspired by this interrogation. I look for ways to interrogate language in my daily life. One key finding within Silliman’s argument is that through this interrogation, one encounters the meager fact that one is left with only “metaphors, translations, tropes” instead of clear windows into the universe. Silliman states, “That these models have a use should not be doubted—the relationships they bring to light, even when only casting shadows, can help guide our way through this terrain.”1 So one is left with shadows to guide one’s way toward this new future, this new light, this new world. Shadows, however, are often perceived through the lens of horror and mystery. What lurks in the shadows is seen as there to cause harm, to take one away from the light. These shadows have been baptized in language through the process of naming that has occurred within the United States and other imperial countries across the world: terms associated with slavery, displacement, and bordering, such as “plantation,” “reservation,” and “borderland.” Today these names have evolved into the various shadow sites that BIPOC communities continue to call home. As a result, the people populating these sites are then left vulnerable to violence because they lurk in the shadows. They pose a threat to the conventions of US daily life: a life of whiteness, a life in the light. The conventions, this light, associated with whiteness require protection through any means necessary (like triggers, bombs, and maybe even poems).

Nature and our environment also fall victim to this naming. The idea of nature has long been used to define what is other than human. Within the United States, one of the names given to this out there is “wild frontier.” Scholars Nick Estes, Melanie K. Yazzie, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and David Correia write:

The “frontier” in the settler imaginary is depicted as a geographical location freely available for the inevitable expansion of settler society. But “the frontier” in the settler imaginary is a people not a place. The frontier is defined as an uninhabited wilderness only through a very specific kind of settler alchemy in which Native people, living in a “state of nature,” require the settler. And this is true whether we are talking about the violent dispossession of Native land by armed settlers or the romanticized notions of Native spirituality celebrated and practiced by New Age wealthy white people sweating in lodges in Sedona, Arizona.2

The dynamic between the frontier and the home shares the relationship of masculine and feminine spheres found within gender construction. The frontier is positioned within the masculine sphere, and the home is positioned within the feminine sphere. Masculinity, then, exists external to the home, within the out there. Positioning masculinity within the external sphere automatically posits violence as a natural and inherent behavior. After all, the frontier needed taming, and this called for violence. In an interview with Seth Meyers, author Ocean Vuong discusses the way we use a lexicon of violence to celebrate masculinity. For example, “you’re killing it” and “you are making a killing” are normal phrases that exist in the external sphere as a way to celebrate destruction. In the same interview, Vuong discusses the way that names can operate as shields for weaker children. This belief informed the mother in his debut novel in the naming of her son.

My mother, too, felt the names she gave her sons were shields. For as long as I’ve known her, she’s kept a Bible next to her bed or elsewhere in her room. She isn’t at all religious in the sense of a specific identity. My mom takes small steps into faith. One of those steps was an intention to name her children after the disciples Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Being the oldest, I received the name “Matthew,” or gift from God. The brother who followed me was given “Mark,” a name associated with war. With our younger brother, my mother broke from her initial purpose: rather than naming him “Luke,” she kept the theme of M and named him “Mitchell,” meaning like God. I imagine the way she named us was her attempt to protect us, one of her small steps into faith. It all begins with names and the language one uses to step into the universe.

So if naming influences violence, each name should be interrogated. Therefore, this essay is not an essay. This essay is not a poem. My name isn’t my name. Natalie Diaz attempts this very unnaming or renaming in her poem “From the Desire Field.” She writes, “Let me call my anxiety, desire, then. / Let me call it, a garden.” Reflecting on this poem, Diaz comments, “In these ever-green wind-bent star-strewn blades of worry and field, spinning until lost, I can rename the burdens of my heart—and offer the body back to language, to be carried, to be grinded into love and what is good. What if I call my anxiety desire? What if I rename this terrible thing as wanting and blossoming with touch? Why not let all bodies—my own body included—be the beloved and possible of offering me a smooth place to rest?” The possibility of giving ourselves back to our bodies through language is worth visiting and revisiting in our desire for the future. So rather than call our current anxieties anxiety, we should attempt to embody ourselves again and dare to call what we feel desire, hunger, want, but also proclivity, capacity, possibility. It is through language that Diaz is able to make this declaration of self-love. Diaz’s interrogation of language within the poem is something to be desired. How can we find an opening, a door, a way in? How can we move toward rethinking the way we use language?

Let me call this essay an opening.

One primary function of language is communication. In my first-year composition courses, I often tell my students about the way classrooms have been a mechanism of removal for Native people. I also talk about the way English rhetoric is passed down to us and forces us into molds. As Jaquetta Shade-Johnson notes, this rhetoric often consists of besting your opponent, winning the debate, dominating the field. English composition teaches students that argument is the basis of rhetoric.3 The entire purpose of these composition courses is to teach students college-level communication, which primarily involves research and argument. As such, the process of research is grounded in the spirit of dominance. It’s no secret that research projects have been awful and predatory for Native and Indigenous people across the country and the globe. The essay becomes a container for domination and destruction, and still I teach it to my students.

Native scholars have been interrogating the essay, and it often starts with naming and language. G. Lynn Nelson, in the introduction to his textbook Writing and Being, states:

This is not a book about writing. This is a book about people writing. It is about writing as a tool for intellectual, psychological, and spiritual growth. It is about our language and our being and their powerful interconnectedness, which have often been taken away from us without our even knowing what we have lost. This book is about taking back the miraculous gift of our language and using it as an instrument of creation.

The point of making a textbook not about writing but about people writing is to help students understand that writing is a human act. Communication is a human act first and foremost. While rhetoric is grounded in dominance, communication is inherently universal and powerful. Nelson’s renaming and relanguaging of the composition course is an important first step to rewiring reality. Language becomes the opening.

The essay is a still lake. Hear frogs talk with the sunset.

Scott Richard Lyons asks the question, “What do American Indians want from writing?” He then renames writing as a technology. Indigenous people can use this technology to remember and reclaim the losses of colonialism.4 As the world furthers itself into ruin, advancements in technology do not seem to slow or plateau. Each year, it seems, something makes us marvel and moves us closer to the sci-fi realm we’ve enjoyed in books and on screens. Robin Wall Kimmerer, in “Corn Tastes Better on the Honor System,” talks about ancient technology and the way Indigenous people engineered agricultural systems before the rise of modern science. I think of Diné weavers, as I tend to do, and their knowledge of the mechanisms of the upright loom and the advanced mathematical considerations needed to produce concise and brilliant rugs; again, all before modern science. If, in the past, our ancestors engineered and manufactured sophisticated systems of expression, wouldn’t ancestral narratives be part of that technology? Technology is defined as the application of knowledge through engineering and industry with a focus on machines, equipment, hardware, software, coding, data, and the language of computers. Technology is often seen as an inorganic thing. However, Lyons’s renaming of writing as technology opens technological space to universal processes. It makes technology organic. Bojan Louis, in defining the Diné concept of Hozhó, talks about the “machination of existence” and the way the Diné universe provides order and balance to all things in a kind of machine.5 Language is a tool of upkeep for that balance. Language becomes equipment, then. Language becomes machine.

Diné weavings are also machines, in a way. At least, their production is factorylike, crafted by organic machinery. I think of weavings as a technology in that respect because they have a function. People were meant to use weavings. Today weavings are considered art, but their intended existence within the world is rooted in function. Storytelling is also rooted in function. I believe that art and function can exist together. A thing can be both function and art, both machine and beauty, both manufactured and organic. It’s like breathing. We inhale and exhale in a systematic process designed over millions of years of evolution. Technology gave us life, and one shouldn’t fear to reclaim technology as an organic thing. While I’m not ignorant of the injustices that exist within our current climate, I have faith in language’s capacity to change the world, even the English language. Lyons argues that Native people have often had to rely on written language in their pursuit of sovereignty because that’s the coding of our reality. However, in this pursuit of sovereignty, Native people are free to change the coding and determine their “own communicative needs.” Language becomes the primary way to open up one’s world. Each word becomes a cog, an exhaust pipe in the machination of existence. Language doesn’t require coal, natural gas, or nuclear power. It’s an inherent gift and can be used to venture out into the unknown.

My name isn’t my name. My name isn’t just my name.

My name is about beauty, something more.

Viola Cordova defines the concept of cultural relativity in her essay “Language as Window” as the way Western constructs constrict worldview to one single thing and dismiss differing worldviews. However, Cordova, through an analysis of the work of linguist Benjamin Whorf, states that language is the key to interpreting the world in different ways. Using an egg paradigm, Cordova asks us to imagine the Earth not as a physical rock in space but as the yolk of an egg. She asks us to imagine ourselves swimming through air rather than walking, and to consider ourselves within something, not on something.6 Seen this way, the Earth becomes a womb, a nest, an embrace.

Beauty is often interpreted as utopian, but beauty is actually the progression of one’s life. It’s the way we move through the world. It’s the dinners we cook, the way we scrounge for our transit pass, the asymmetry of our faces, the way we stretch, the tears, the way we take deep breaths.

Our landscapes are often considered part of the frontier, the out there, the sphere related to masculinity and violence. An early United States needed to name the wild frontier as opposite to American progress and used the landscape and its Indigenous inhabitants as scapegoats and necessary sacrifices. The necropolitics that inform this naming place both the Native and the natural landscape as other and, consequently, marked for death. Our language today is still much informed by this structure. One can see phrasings such as “the wild west” as reminiscent of the termination era of federal US policy. The very notion of the US pursuits of liberty, life, and happiness requires the displacement and disappearing of Indigenous people. I use “disappearing” purposefully here because not even death is an escape from US myth. Native imagery often requires the reanimation of Native ancestral identity. Today, Native ancestors are often paraded around as rhetorical tools. As Cordova continues in her essay, the context of being Indian is displacement and erasure because of the language we employ. Language matters: it matters to our reality. The very constructions by which we design our lives begin and end with words.

I’ve talked before about how the land often acts as memory field, forever holding on to space and time as resistance to conquest. As stated, the conventional US daily life requires displacement and disappearing. It requires the naming of land as the frontier, as out there. This naming leaves the land itself susceptible to violence. Recently, I’ve been thinking about the ways we can rename land as a domestic space. In doing so, I believe we can begin the process of relanguaging our reality. Nature and environment are often considered opposite to domestic spaces. Capitalism requires this imagery to sell outdoors-related items. Labeling land as domestic may seem like a hard sell, but it has been done many times in the past. If one looks to suburbia in the US as a privileged movement from cities to the fields outside cities, one can see the way US markets already control the narrative of land. Prior to that, Abraham Lincoln renamed frontier lands as seed money when he signed the Morrill Act, which developed endowments and foundations for many universities and colleges in the US. Today the United States continues to control the narrative of land as it permits pipelines and drilling to continue despite the current climate crisis.

There have already been attempts to relanguage the narrative of land. Land acknowledgments have risen in popularity as many begin to acknowledge their occupation as part of a continuum of expropriation, theft, (un)cession, and legislation. While flawed, land acknowledgments do recode land’s existence within the US. Further attempts at renaming are possible. Writing, as an act, becomes one way forward if we follow Lyons’s argument that written English is a technology of reclamation.

My name is beauty.

I know how all of this sounds, and it can really be misconstrued by new age spiritual movements. I have a huge fear that someone will run to Sedona, Arizona, with my essays and words and create cultlike prayer circles and make millions. However, that’s the risk we take with language: it creates reality. In my Introduction to Poetry course, I asked the class to watch a scene from The Matrix through the lens of language as code: the scene where Neo is able to see the matrix as it is—lines of code, capable of manipulation. I used this as a very weak metaphor for the job of the poet. There is a certain kind of manipulation that happens on the page. Poets are unlike novelists or essayists in that way because they suffer over the smallest alignments and misalignments within language. Some call it code, some call it magic, some call it cryptic, some call it magnificent. In my poetry workshops, I call it the extrinsic materials of a poem: the production, manipulation, experiment, interrogation of language. It’s a matter of looking for beauty. But what is beauty? How do we feel beauty in the shadows? How do we make time to seek beauty?

John O’Donohue states, “Beauty isn’t all about just nice loveliness, like. Beauty is about more rounded, substantial becoming. So I think beauty, in that sense, is about an emerging fullness, a greater sense of grace and elegance, a deeper sense of depth, and also a kind of homecoming for the enriched memory of your unfolding life.”7 Beauty is often interpreted as utopian, but beauty is actually the progression of one’s life. It’s the way we move through the world. It’s the dinners we cook, the way we scrounge for our transit pass, the asymmetry of our faces, the way we stretch, the tears, the way we take deep breaths. It’s the becoming we do, the emerging, the arriving. In a way, naming ourselves in beauty, for beauty, and about beauty recenters the self. We unburden ourselves of utopia and call the way we move through the world utopia. We ooze beauty.

As an undergraduate, I launched the Rez Condom Tour, a DIY community project dedicated to increasing access to sex education on the Navajo Nation. Informed by my courses in body sovereignty, I tried to find on-the-ground ways to enact some kind of change. Today, the Rez Condom Tour is led by Faith Baldwin and Keioshiah Peter, who continue to spread body positivity on the reservation. I started the tour because I noticed how sex education wasn’t seen as a priority for students on the reservation. I looked to my own experiences in high school and college, attempting to buy condoms with no money. The tour was funded through our own money, and we sought donations and volunteers to hand out condoms to the community. Then, during my years as a writing tutor for Diné College, before I was hired as an instructor, I organized a daylong festival called “My Name Is Beauty.” I wanted the day to be filled with discussions on body sovereignty, including sex education, consent, and self-defense, as well as a workshop on traditional foods. Again, running on personal funds and volunteers. I wanted participants to see the way their bodies are inherently beautiful, full of wonder and surprise, hence the naming.

In titling this essay, I wanted to again convey the way our existence is rooted in beauty and how beauty is sustained by the way we engage with the universe. Like gravity, like language, beauty moves through space and time. It’s impossible not to live with, in, or about beauty. A Diné prayer, “walk in beauty,” has been popularized as a mantra across the internet. A simple Google search will show you the numerous ways this teaching has been appropriated and redefined through many lenses of being. The mantra tends to go like this:

In beauty I walk,

With beauty before me, I walk

With beauty behind me, I walk

With beauty above me, I walk

With beauty all around me, I walk

With beauty within me, I walk

In beauty, it is finished

This blessing, of course, does have many functions within Diné traditions, prayers, and stories. While its meaning is more intentional in Diné, the idea remains consistent: beauty exists and we exist along with it. And that is an odd way to perceive the world when so many voices teach us to view the world through shadows. But what is shadow if not the language of light? And darkness, the language of morning; grief, the language of time; body, the language of Earth; and beauty, the language of the universe? And language is still an invented thing: a spark on a cavern wall, the tongue dancing beneath teeth, a click of a pen or keyboard, a tap on the microphone.

So in our reach for a new world, let’s think of language with intention: the word as seed, the sentence as cornstalk, the paragraph as bloom, the essay as body; and the period as an emergence, the comma a hope, and the question mark a sunrise.

- Ron Silliman, The New Sentence (New York: Roof, 1977), 3–4.

- Nick Estes et al., Red Nation Rising: From Bordertown Violence to Native Liberation (Oakland: PM Press, 2021), 31.

- Jaquetta Shade-Johnson, “Writing Our Stories: Constellating the Field, First-Year Writing, and Tribal Colleges” (lecture, Still Sacred: First-Year Writing at the Tribal College Virtual Conference, Diné College, May 12–13, 2021).

- Scott Richard Lyons, “Rhetorical Sovereignty: What Do American Indians Want from Writing?” College Composition and Communication 51, no. 3 (February 2000): 447–468.

- Louis, Bojan, “Nizhoní dóó ‘a’ni’ dóó até’él’í dóó ayoo’o’ni (Beauty & Memory & Abuse & Love),” in Shapes of Native Nonfiction, eds. Elissa Washuta & Theresa Warburton (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019), 55.

- Viola Cordova, “Language as a Window,” in How It Is, eds. Kathleen Dean Moore, Kurt Peters, Ted Jojola, and Amber Lacy (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2007).

- From Krista Tippett’s interview with John O’Donohue, “The Inner Landscape of Beauty,” On Being, 2017.