Melanie Challenger researches and writes on environmental history, bioethics, and philosophy of science. Her books include How to Be Animal: What It Means to Be Human; Animal Dignity: Philosophical Reflections on Nonhuman Existence; and On Extinction: How We Became Estranged from Nature, which received Santa Barbara Library’s Green Award for environmental writing. She has written for several publications, including New Scientist, The Guardian, Aeon, Nautilus, and BBC Science Focus, and has participated in documentaries and film for the BBC, CBC, Arte, and ZDF. Melanie serves as deputy chair of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a vice president of the RSPCA. She was part of a team who drafted the first Declaration on Animal Dignity in 2024 and is a founding member of Animals in the Room, a project that seeks to expand democratic imaginations to explore how animals can be present, participate, and be represented in the decisions that affect them. In 2025, she became a National Geographic Explorer.

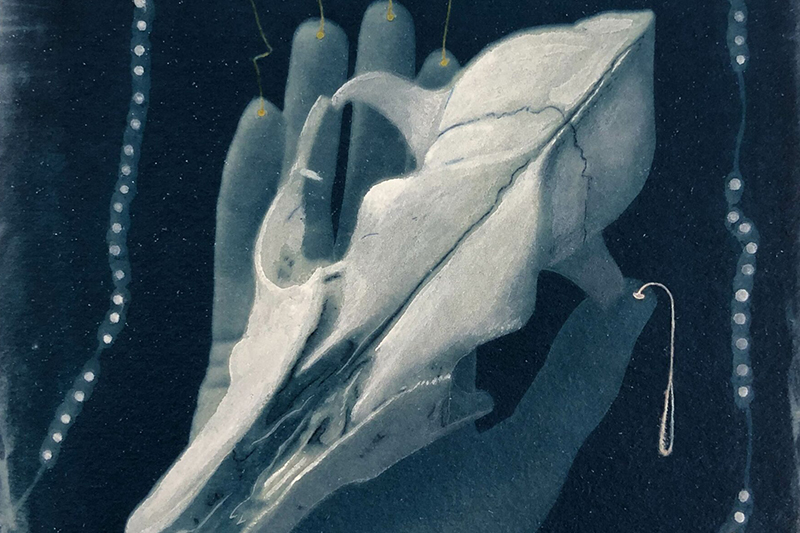

Annie Marie Musselman is a photographer whose work is inspired by a belief that true kinship with animals can transform our lives for the better. Her award-winning photo books include Finding Trust, Wolf Haven, and Lobos: A Mexican Wolf Family Returns to the Wild. Anne Marie’s work has appeared on the covers of Audubon, Smithsonian, and Outside magazine, and inside The New Yorker, Rolling Stone, National Geographic, and The New York Times, among others.

Listening closely for what her nonhuman neighbors are communicating, Melanie Challenger considers what it would take to expand the democratic imagination to include and represent animal voices in the decisions that affect them.

Come with me into the forest that is now only a forest in my dreams. And it is often in my dreams these days. I return some nights, walking, unthinkingly, because I know every landmark, every turn. In these dreams, I reach my old home, deep in the forest, a small house we rebuilt from a state of near ruin, where I raised my two young children. The sensation is like that which accompanies the appearance of ghosts in dreams. At first, all is familiar, then comes the creeping sense of distortion. Despite the seeming absoluteness of the dreamworld, somewhere in me I know this is not my home anymore, just as one comes to realize, looking into the face of a lost loved one, that they aren’t really alive, and with that awareness the uncanny skew as the sleeper, briefly tricked by their own double reality, senses the mirage and falls through to the solidness of a world in which what seemed a moment ago to be material is now only chemical memory locked inside the grief of the body.

It is hard to admit, when you have left your home of your own volition, that you are homesick. Especially when you know you can’t return.

But I don’t want to give the wrong impression here. I don’t really miss the house itself. What I miss is the community. Every morning, I woke to the sound of trees. Forest-sound is like an ocean that has been suspended above the ground. And I woke, too, to the scratches of rodents in the attic, the telltale scrabble of nest-making. Sometimes I could hear the bats that gathered in the eaves. In the summer, I would leave the window open just to listen to the chittering of the swallows on the cable outside, their voices like air squeaked through impossible holes.

On the drive to school, especially in the winter months, we would greet the old hare who lived at the tree line of larches above our home. If he threatened to run on and on, we would stop the engine and turn off the lights to let him bolt into the trees. In spring, we would greet the green woodpeckers, their undulating flight tugged and lowered by an invisible master.

We didn’t live among humans, you see. We lived among other animals and plants. And we miss them. Acutely. And that feeling has grown over time and surprised us. I remember the first time it hit us, while the kids and I were out walking another strip of woodland by the village where we now live. As we ascended the slope, my youngest son said, “I think I miss the animals.” And I found myself stifling a sob, which was unexpected, especially as I’d done my best to bury all feelings about the move. But I knew I missed the animals too. And it was hard.

I had never had a strong sense of belonging. In fact, I’d been a deeply fidgety kind of person, always seeking out new places and experiences. I grew up on a housing estate in a small town. I couldn’t have put my finger on it at the time, but it was too human. And I don’t mean that unkindly. It’s just a simple fact. The other species that must have once lived in that landscape were mostly gone. And at some ambient level, I was missing them too.

When, in adulthood, my husband and I bought the house in the forest, in all its shambles, we hadn’t banked on the way our nonhuman neighbors would come to matter to us. Yet ordinary, everyday proximity to other life-forms makes plain that they have vivid experiences of the world around them. The wild lives of other species are punctuated by the dynamism of the unexpected. They aren’t endlessly running on algorithms, strung to nature’s deterministic loom. Animals hesitate if something grabs their attention. They take advantage of a sudden outbreak of sunlight, or not, as they see fit. Some individuals are more curious than others. They make choices between alternatives, in ways that are not always predictable and directed by individual character. And this is only possible in beings with agency and feeling. In simple terms, they are gloriously, staggeringly, idiosyncratically alive.

And so, what an idiot I was not to have understood this until that moment. “I think I miss the animals.” Of course you do, my love.

Because, we don’t miss the forest and the animals as a painting or a backdrop. We miss them as familiars, as kin. We miss that rich, diverse community of beings. And we miss them not because of some fanciful, sentimental anthropomorphizing, some intellectual weakness in our characters. We miss them because anyone who develops deep knowledge of other species by living alongside them for years realizes something both obvious and essential: we are not the only lives that matter.

And yet, in so many parts of the modern world, other animals are treated as objects rather than as subjects. In nearly every postindustrial country on Earth, from the USA to the UK to China to India, other animals have almost no legal protection whatsoever, except that which is conferred through us. By that I mean unless an animal is our property or gains status as a member of a protected species. Animals are not subjects of justice, but objects of human impulse. And one of the chief reasons we starkly divide the world between humans that matter and nonhumans that don’t is that animals can’t speak for themselves.

It is often said that animals are, in some sense, silent. They grunt, yes. Or call. Or cry. Some of them sing. Some hiss. But they have no voices. They do not speak. They are silent because they lack both language and the minds that structure and generate meaning. Even those who argue for compassion towards nonhuman beings have historically perpetuated this idea. Consider one of the landmark publications in the animal advocacy movement. Our Dumb Animals was the title of the magazine published by the Massachusetts Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals from 1868 through to 1970. As the motto went, “We speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

Sometimes we consider other animals silent because we can’t detect their communications. The research of zoologist Gabriel Jorgewich-Cohen hit the news recently when he and his colleagues released a study of fifty-three species previously considered nonvocal. The research was focused on turtles, which, through painstaking recordings and analysis, were found to communicate vocally across multiple species. Encouraged, the scientists expanded their study to other species of choanate vertebrates—vertebrates with lungs—and found further evidence of vocal ability among previously “silent” species. The assumption now is that vocalization—the ability to push air through the lungs, creating sounds in the structures of the throat—has an ancient history stretching back to the origins of choanate vertebrates, and probably even earlier. For hundreds of millions of years, then, thousands of different species have deliberately harnessed their breath to communicate with mates, aggressors, offspring, and strangers.

Of course, not all communication is vocal. Even in a highly expressive animal like us, large quantities of information are conveyed through facial expressions, body position, eye contact, and hand or limb gestures. I once found myself peering into the clear waters of a research tank, watching the chromatophores of the Humboldt squid flash and freckle with deep pinks and red wine colors as the males challenged one another for access to a female. For some animals, then, color is connection.

For others, such as silk moths, communiqués come in the form of pheromones. And this sort of chemical signaling is not all about sex. Other insects, such as ants, have alarm pheromones, as described in the 1960s by E.O. Wilson, that warn the whole colony of an approaching danger.

Yet many of us argue that only humans have language, and so only humans can speak (or think) for themselves in any meaningful way. The uniqueness of our communication, it is claimed, lies in the combinatorial quality of human language, made possible by certain cognitive capacities. In other words, our ability to bring together novel and abstract meanings to an infinite degree.

It is undeniably true that our communicative strategies are unique across the tree of life, but human language is also reliant on a range of adaptations that have continuity with characteristics or properties common to many other species: both unique and continuous—the hallmarks of evolutionary process. Why must we always center our attention on what we believe is special or distinctive rather than what is shared?

Most often the obsession with our linguistic uniqueness begins with our need to justify the exclusive moral and legal standing of humans. But while language matters to humans, it isn’t what makes humans matter. Some humans lack the ability to communicate with language. Some of us lose the gift along the way. None of these individuals are considered any the less human for it. Language gifts are understandably significant, but they don’t make the lives of other species either silent or insignificant.

A better question is a simpler one: why do life-forms communicate in the first place? Any life-form’s expressive or communicative strategy is an extraordinary reminder of the consequences of evolutionary processes on beings that are going about their lives with purpose. At some point, several billion years ago, a sequence of molecules combined and self-replicated such that evolution kicked in and some of the materials of our planet began to move and do things in pursuit of their persistence. Life looks like chemistry with a plan. And living beings have since inherited many capacities to pursue their interests with guile and sensitivity because such capacities gave them a crucial edge over those without such smarts. Communication systems, even poetic, recursive ones such as ours, were inherited by lucky descendants because they are useful to organisms.

This foundational truth is the reason we are so good at intuiting what another animal seeks. Other animals, in turn, keep a watchful eye or ear on us too. It pays to figure out another animal’s intentions either first or fast. It pays to be able to read cues and signals, even from a very different kind of organism. And this holds just as well within species. We often learn most efficiently what another person needs through their physical action and facial expression alone. When speed is of the essence, a quick glance is more effective than a chat. Sure, it’s delightful to chew over the complexities of Wittgenstein’s theories on language, if you’re so inclined, but when disaster is coming, the best thing to do is scream.

So, consider the following. A raccoon dog is taken from the wild by a rural farmer and brought to live inside a ramshackle cage, where it awaits the day it will be skinned for its fur. This animal happens to carry a virus it picked up from another wild animal it has recently eaten. But because this animal now lives in unnatural proximity to hundreds of other raccoon dogs, this virus spreads and mutates. And this virus can pass to humans. Days later, the now infected farmer boards a train. He enters a densely populated city unaware he is shedding a new virus among his fellow countrymen.

We don’t know if this is what happened with SARS-CoV-2. But we do know that a scenario like this caused the first SARS outbreak in 2002, which spilled into humans from bats via the Himalayan palm civet, farmed and slaughtered for the perfume industry, and the raccoon dog, killed for its fur. And we also know that most emerging diseases of the past century have originated from our exploitation of nonhuman animals.

China isn’t alone in experiencing spillovers of pathogens from captive animals. Around the world, billions of wild and domesticated animals experience brief, unpleasant lives, far removed from the ecological conditions to which they are adapted, because they have become part of the economies of humans. In the UK, we’ve had bovine spongiform encephalopathy, or mad cow disease, from feed contaminated with a prion agent. The 2009 swine flu pandemic likely began on a pig farm in central Mexico. The opportunities, from the perspective of the millions of pathogens in the world, are rife and global.

According to Germany’s leading virologist, Christian Drosten, animals killed for their fur are sometimes skinned alive. “They emit death cries and roar, and aerosols are produced in the process.” Drosten was one of the scientists who uncovered the original transmission pathways of the first SARS outbreak. He notes that the animals’ screams likely made it easier to infect the humans doing the skinning. That is a sobering thought. What is a “scream” for, if not to communicate the interests of that animal in the moment?

We have heard so many voices throughout this pandemic. There are ongoing demands for justice. There are enquiries. The apportioning of blame. And hundreds of protests have taken place. In March 2021, over thirty thousand individuals even marched London’s streets to protest for the right to protest. Protest is a means of demanding change for those without other forms of power. Of course, protests are blunt tools. But they can work. They make use of physical presence, along with songs, yells, or chants, to communicate defiance of the status quo.

In their presumed silence, other animals, we imagine, can’t protest in any political sense. And therefore, they can’t dissent in ways we might recognize. But in the winter of 2020, a team from the Humane Society International captured footage of animals farmed for their fur in China. Using covert cameras, they secured evidence of wild animals housed in rough brick and wire cages, caked in filth and fur. One investigator from an associated organization said that a fully skinned animal on the pile was conscious and able to raise its head for ten minutes before dying. The footage makes it clear to anyone that animals use their bodies and their voices to protest their conditions: they protest the miserable lives they are experiencing and their deaths. Just imagine for a moment if we listened to them.

Anyone who develops deep knowledge of other species by living alongside them for years realizes something both obvious and essential: we are not the only lives that matter.

Now step with me into another memory of the forest. It is spring 2020. My sons and I are out hiking one of the trails. The pandemic has created a new kind of quiet here. We stand still and listen as if our whole bodies are instruments of purpose. We listen not as logic machines but as Tibetan singing bowls. We let the silence strike us and we let the silence persist.

We stand like this for ten or fifteen minutes. This is highly unusual. My young sons are full of pent-up kinesis, like a sprung trap. Normally, they run about the place, kicking up the dust in a hullabaloo. But they restrain themselves today because the world has changed. And they want to listen.

We hear a ten-thousand-year-old silence. A wild silence. An ice age hush. A silence through which we might catch the outbreath of a mammoth. This is history without the combustion engine and without domestication and perhaps even without God. It is a truly old-timey quiet and all three of us know we will probably never hear silence of its kind again in England—or perhaps anywhere. The uncanny quiet of the pandemic allows us to hear our neighbors with a new clarity. Close by us an adder samples the air. Its biblical silhouette, slow and impossible, moves between the grasslands like a feral current. Rabbits, young and old, play in the grasses unconcerned, flicking in the air in that electric way. A roe deer stops a few feet from us and stares for five minutes or so. The lightless pools of its eyes move over us, weighing, as if to get a proper look for once. There are peacock butterflies and small tortoiseshells praising on the grass tips. The glow of a single green hairstreak on a coltsfoot. How quiet does it have to be to hear butterflies? In the hush, we can hear their old-skin crackle. But we aren’t the only ones that sense the change. The voles and hares and lizards have noticed. The wrens and meadow pipets have noticed too. And the long-tailed tits. Each of these different beings—going about their private necessities, processing their unique erotic or gustatory lifeways—has been listening whether by ear, by tongue or by the cock of their heads. They know, just as we do, that the sound-world has shifted.

For that briefest of spells during the first lockdown, many around the world could suddenly hear those with whom they share the Earth. Our towns and cities, our countryside, and our nations aren’t only human worlds. They are mixed communities of thousands of different species.

In the 1960s, political philosopher Hanna Pitkin wrote that to “represent” those who might be marginalized or ignored within a community is fundamentally to “make [them] present again.” By her definition, representation in this political sense makes the voices, perspectives, and interests of the less visible members of a community present in the decision-making spaces where they are otherwise absent. The pandemic made other species more present to many of us. But, like others, I began to wonder whether this re-presentation might be possible on a larger and more formal scale. Not just possible but necessary.

But how do we represent the voices of nonhuman animals? It was that challenging question that kept me awake at night during the pandemic. And it led me to fire out a series of emails in the winter of 2020 to colleagues and various scholars already doing significant work on animal welfare or political representation. My hope was to convene a group of experts to attempt to listen to nonhuman animals in situations where we are making choices and decisions that might cause significant harm or transformation to them. The function of this listening would be to recognize any “political” signals that might emerge from the voices or behaviors of nonhuman agents.

What has resulted from that first email is a collective of international scholars who have been engaging in a series of robust, open conversations about how such representation might come about and in what contexts. The ideas that emerged from these conversations (which were themselves reliant on patient listening of different views across different cultures and experiences) are now being put into practice in our first proofs of concept.

Erin Ryan, one of the members of this group, came up with the name for our project, Animals in the Room, provoked by a transformative moment she’d once had when witnessing a cow-calf separation during her veterinary studies. “I watched the cow give birth, and we had to take her calf away. And it was profoundly obvious that she had a relationship to that calf, and to us, that she articulated in the barn before, during, and after the event. I didn’t want to do it or be a part of it again.” From then on, it became Erin’s dream to represent the lives of animals in a more fulsome way. Animals in the Room is now an international collaboration of philosophers, scientists, and animal welfare specialists working together to devise and test the best ways of representing nonhuman animals in decision-making. Crucially, this representation is founded on working with the animals to communicate their interests on their own terms. In other words, we act from the belief that animals aren’t remotely “dumb.”

Today, when humans think about what’s right for a nonhuman animal, either ethically or legally, the ideas start and finish with us. “Procedural justice requires that in a democratic community everybody that is going to be affected by a law or action—the ‘all affected principle’—has to be included in the construction of that law, however we end up instituting that,” explains Danielle Celermajer, another of our collaborators and a professor at Sydney University. In theory, if the process is just, then we’ll reach more just outcomes. Of course, the obvious difficulty is that our decision-making systems have been designed around human language. To overcome that language hurdle, one of the fundaments of our work is to allow other animals to define their own good. This requires us to recognize that animals can both express themselves and determine what’s in their best interests. Once animals are empowered to speak for themselves, they become subjects of justice. The trick is in re-presenting that “speech” inside the halls of power.

What might the content of such representations be, and how could they work in context? Cary Wolfe, professor of English at Rice University, argues that the first step is to pay attention to the particularity and singularity of each life-form. “The first thing we have to do is de-genericize nonhuman life and listen to the vast differences between a bottlenose dolphin and dog,” he says. “The science shows that the more we learn by listening about these creatures, the more the heterogeneity of the nonhuman world has just exploded before our very eyes.”

The forest we lived in was an industrial forest, with large sections of woodland logged on rotation. This was a large part of the reason that we left. We began to dread the felling of whole stretches of trees with which we had intimate memories, from childhood parties to the traditional fungi surveys that dominated our autumns. (One of my youngest son’s first words was an approximation of “mushroom,” which shouldn’t surprise anyone who has lived in a forest.)

When a felling operation was due to take place, we would receive a formal letter, detailing the times and areas that would be affected. And we often received a visit from the forest manager too. As residents of the forest, with shared access across the government’s land, there were various lines of communication open if there was a problem or if we encountered any issues because of the work. The Forestry Commission employed ecological surveyors, and they were sensitive to managing stretches for biodiversity, which included the marking of anthills with pink, fluorescent sticks so that the loggers would avoid them when the machines came in.

Still, we knew where many of our neighbors lived. And we often wondered what it must be like to return home and find everything gone.

For three years in a row, for instance, usually on the first warm day in late February or March, we would see an adder basking in a particular spot close to our driveway. We placed a small cairn by the road, so we knew the spot. And, sure enough, each spring, an adder would emerge from the hibernaculum that must have been close by, maybe the same male, and sun itself. This would continue for a week or two before the animal would move off in search of opportunity.

But one day we returned home to find that the Forestry Commission had regraded the roads. This was a welcome event for us because the miles of dirt track could become almost impassable without occasional regrading, but we could see that the whole area favored by that adder was gone. We never saw it on that spot again.

Adders have remarkable abilities to sense their environment and each other. For one thing, they have keen eyesight. For another, they “hear” through their skin and the tiny bones of their jaw, carrying and interpreting the drumming messages of the outside world through their body. And they “smell” with their tongue, gathering the molecular traces of others through miniscule openings in the roof of their mouth, tucking them into their olfactory centers. Their communication with each other is largely chemical, a calligraphy of pheromones that can stretch for miles.

My suspicion is that the regrading of the road disturbed the hibernation site from which that adder routinely emerged. There can be dozens of individuals hibernating together under the earth in such spots. After the roadworks, as far as we could tell, there were certainly fewer adders in that area for several years.

Adders are a protected species in my home country because they’ve been persecuted and have lost habitat through human expansion. And so, disturbing the lives of adders matters up to a point. Yet, protection largely comes in the form of mathematics: we protect adders as a homogenous whole from going locally extinct, which means that there are some limitations on what can be done to them and their homelands. But, if a road needs repairing, there’s no missive for the adders. No effort to decode their language and confirm their presence. The assumption is that the adders will just move elsewhere. Who would dream of consulting them first? Absurd, right?

But what if we did? There has been a recent swell of interest in the communicative strategies of other species. In her recent book on animal languages, philosopher Eva Meijer argues that the fear of anthropomorphism has led us to underreport what we can know from other animals. “Only an entrenched belief in a biological hierarchy set by a Christian God,” she writes, “prevented us from listening to other species properly.” Other species, Meijer points out, employ forms of imitation, light displays, movements, sounds, gesture, chemicals, and scents to convey information to others. Each day, we are learning more about the significance and complexity of these expressions. As such, the weight of scientific evidence allows us to recognize that other animals can communicate their presence and their needs and interests. This ought to suffice for us to recognize other animals morally. The question is: would “listening” to these animals make a difference to the outcome of a decision that might affect their lives?

The first hurdle, once we recognize other animals morally, is to facilitate representation. Another of my colleagues, the political philosopher Alasdair Cochrane, uses the word “intertwined” to convey the fact that we live in multispecies communities. These other beings are part of what it means to be a citizen of the United Kingdom or a resident of New York. But while the human residents of our communities have many well-established methods of political and legal representation to ensure their interests are sufficiently present when life-altering decisions are made, there is no such recognition for other animals.

In the past few decades, philosophers and social scientists have focused on democratic process, and on forms of “political listening” that encourage us to pay attention to the voices of those that will be affected by major decisions. Something like the concept of political listening was put forward by political philosopher John Dryzek as a potential way of acknowledging and addressing the needs of nonhuman animals. More recently, Martha Nussbaum has suggested the use of “ethograms”—a catalogue of behaviors and needs of an organism based on observation—to identify a fundamental threshold of necessities and capabilities that establish an animal’s basic rights. Many of our members have also called for special representatives of other species as a necessary step for global justice. But how do we attempt to bring these ideas into practice? Who, for instance, is going to represent the voices of adders?

What might happen if, instead of just counting local adders, someone actually listened in on those pheromonal missives and established the places that mattered most to those individuals? What would the process look like if it was necessary for those voices to be heard, for evidence to be presented on their behalf, before a decision could be made?

In most situations, it’s not possible to bring other animals into the decision-making room physically. But we can use image, video, and audio files as forms of testimony. Snakes aren’t often associated with their vocalizations, but, just like the turtles that Jorgewich-Cohen studies, across different snake species there’s a surprisingly wide range of sounds, from the pine snake’s shriek to the infamous growls of the king cobra. As someone who has lived alongside dozens of adders, I’ve been hissed at a fair few times. Like most other vocalizations that snake species produce, these are unmistakable in their meaning: stay back. Would it hurt us to listen or consider the impacts of repeated disturbance? And then there is a wealth of information that animals emit from their bodies, from secretions to facial expressions to bodily movements, that spell out everything from fear to desire. Why not acknowledge them?

We already do something similar in cases where a human individual, by age or disablement, can’t directly communicate their interests. If the right person interprets these testimonies and has no conflicts of interest, we feel that the voice of such vulnerable individuals has nonetheless been heard.

To really listen to other animals, you must gain their trust, and that requires spending time with them. And slowing down.

Like Erin, welfare scientist Becca Franks started out wanting to be a vet, but she, too, realized that she needed to help other species through a different lens. Becca came to animal welfare via a background in psychology. “Up to now, in animal welfare and rights, we’ve had good intentions, but if we don’t make a serious move to have animals speak for themselves,” she told me, “then we risk asking the wrong questions.”

When all’s said and done, we can have a room full of people strategizing how to advocate for animals, but there’s a lack of seriousness if the animals themselves aren’t there. Allowing animals to speak for themselves “means bringing them into the room, and into the deliberations, and trying to quiet our own narratives down and just sit with the animals and be observant.” Fundamentally, it takes time. Currently, Becca is working with koi fish. Through many hours of painstaking observation, she now knows that water flow is incredibly important to them. This is the kind of specific, intimate insight that is necessary.

Our group has now started down the path of working with partners to trial and evaluate representations in different contexts where decisions are being made. Through these trials, we will gain valuable insights into the specifics of “how” and “when” we should represent other species. And we can also test empirically the impacts on decision-making in science, industry, deliberative, and community settings.

Another priority is to evaluate what these models of representation might look like in different regions and cultures. One of our collaborators is Zambian philosopher Julius Kapembwa. There are some large and active animal welfare groups in Zambia, but the animal welfare landscape there is distinct from that of the UK or North America. That is why we need globally minded but regionally designed ways of approaching the inclusion of animal voices in decision-making processes. In Zambia, for instance, the contexts in which early work could apply involve snakes, human-elephant conflict, and stray dogs.

It is likewise important to frame dialogues in terms that are sensitive to cultural nuance. There is an ethics renaissance in Africa at the moment, seeking theoretical frameworks that are African in emphasis. Sensitivity to and knowledge of the specific landscapes in which human politics play out will be essential to any successes in representing nonhuman members of a community. Likewise, different cultures have distinct lived experiences with nonhuman animals. There is much to learn from First Nations communities, for instance, that already have some significant strategies for listening to other species.

Will it make a difference? None of us know yet, but even if there isn’t a measurable change in outcome for the animals, this isn’t a reason to continue making decisions without them. As Becca notes, there’s a principled reason they should be there. “If we’re going to say nonhuman animals have interests in the world, have the ability to communicate those interests, are agents who deserve our respect, there’s no way you can have all those values and not have them in the room for the decision-making.”

Still the obstacles to really listening to other species are formidable, not least because capitalism rests on the capacity to treat nonhuman animals as resources. All large, industrial societies exploit other species in colossal and growing numbers. As Danielle Celermajer told me, our current systems, most especially our food systems, would need unraveling. “It’s tremendously difficult to pull it apart.”

But something that may make the difference is the pandemic. Given the consciousness shock of a global health emergency, and the soul searching it has inspired, especially around how we are treating animals and their habitats, it seems that people are more willing than ever to contemplate a rethink of our relations with other species.

When I think back to that eerie silence at the start of the pandemic, I remember the rich beings whose voices the children and I heard so distinctly. But I’m also reminded of something that Becca said to me. To really listen to other animals, you must gain their trust, and that requires spending time with them. And slowing down.

I realize that it was the slowing down that really made the difference during that strange spring when the pandemic hit. We are a family of obsessive naturalists. Even so, our lives are so fast and so noisy much of the time that we don’t always settle into the right frequency to capture a generous sense of the agency of the other life-forms around us. But that year was transformative. And we were not alone in hearing our wider community so acutely.

As we rebuild a world “after the pandemic,” imagine if the measure of a good and democratic society was one that truly acknowledged other animals and made animals “present” again in our lives? The year 2020 may have been an annus horribilis. But that year, the other, often invisible, members of our communities and our homes made their presence known to us. Let them never be silent again.

On Death and Love

As Melanie Challenger examines the belief in human exceptionalism that has devastated life on this planet, she wonders if our desire to outrun death is hindering our capacity to love.