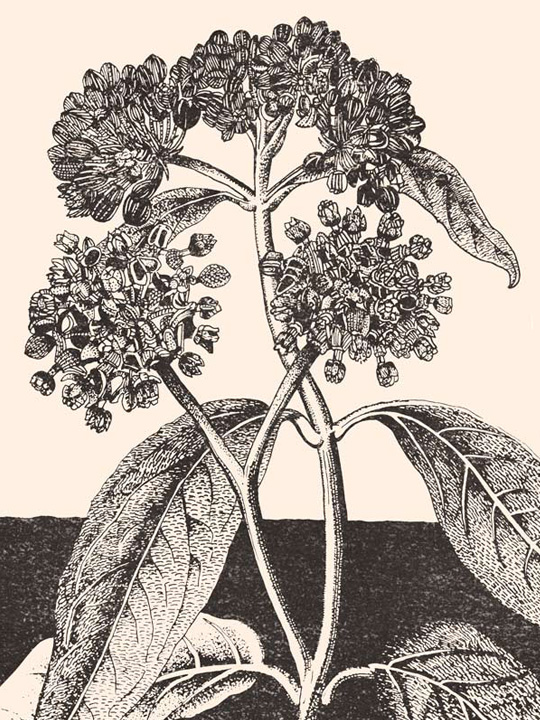

Artwork by Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder

The Way of the Goldfinch

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

Watching a goldfinch sway on a blade of grass, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder writes to her soon-to-be-born daughter about beauty, balance, and lessons of uncertainty.

It’s been thirty-one weeks and you are close to sixteen inches long and weigh up to four pounds. You are most active in the evenings, kicking much faster and stronger than I would have imagined. (I asked my doctor at my last appointment if it was possible that you were moving too much. She assured me no.) We love to feel you moving, your father and I.

This morning I sat on a damp bench beneath the big elm tree at Pleasant Hill Preserve. It was overcast and misting, and the meadow beyond the tree was full of birds: swifts, song sparrows, goldfinches, redwing blackbirds. The air smelled soft, of yesterday’s rain and the marsh and the last wafts of the multiflora rose, which has almost finished blooming. I sat as still and quietly as I could, hoping you could hear the birds singing, and imagining the day when I’ll get to bring you here to see them and smell the meadow, and how I will place your small fingers on the ridged leaves of the elm.

I spend a lot of time these days imagining you being in the world. We just finished a birthing class that quelled most of my fears about labor, replacing them with knowledge of what to expect and a better understanding of the process. We learned how to recognize early labor, how to breathe, what to expect at home and in the hospital, what will happen right after you’re born. Most helpful for me was the reassurance that my body will know what to do when the time comes—and so will you. This has surprised me again and again over the last seven months: that my body and you have known exactly what to do. My growing belly, your stretches and kicks, the sound of your heartbeat at every appointment: all feel like blessings that have occurred without any active doing on my part. I can only marvel.

Everyone I know who’s gone through labor has prepared me for the possibility of the unexpected occurring in the midst of it all. That feels all right; I don’t feel afraid of the process of birth. And most often what I imagine is not the birth itself but the long-awaited moment when they will place you on my chest and our hearts will beat side by side, and I will get to touch and hold you.

There is only one thing about the prospect of being in the hospital that has tied a knot of fear in my chest: I’m afraid of testing positive for the COVID-19 virus upon our arrival at the birthing center. If that happens things will be different. I may not get to have that moment with you. They will recommend that you be isolated from me immediately after your birth. (I will have the right to turn down that recommendation, but at what risk to you?) And instead of feeling you against my skin, I will watch them carry you away.

This fear feels overly dramatic—or, at the very least, unhelpful. Everyone I’ve confessed it to has rightly reminded me how unlikely this scenario is. We’ve been very careful; cases in Maine remain very low. We are fortunate. We are healthy. Even in the unlikely event that this did happen, we would get through it. We will have all the time in the world to hold and love you.

This fear still rises up.

I’ve been trying to practice better acceptance of the unplanned and unexpected, of things not going the way they’re supposed to. These lessons have come in varying degrees over the past several months.

The apple tree, whose early buds I’d held in the palm of my hand in the snow in late February, never bloomed, never displayed its pink-white flowers. Too many late frosts, and so no apples will grow from it this season. But it is full-leafed and green and growing taller, and there is next year to look forward to. The Earth is resilient. It knows how to mend.

The goose nest that I’d watched for nearly six weeks—that I had visited almost daily, with the mother goose there, every day, atop her eggs—failed. The first time I saw that she was not sitting on the nest, I rejoiced, assuming that they had hatched and she and her chicks were tucked away somewhere in the reeds. The next day, I saw her and the gander alone on the pond. I thought maybe they had left the goslings alone somewhere safe, but I knew that wasn’t true as soon as the thought formed. When I looked toward the nest with my binoculars, I could make out the white curve of an egg that had rolled down to the water’s edge: alone, untended, unhatched. I thought of how she had sat on those eggs for weeks, in rain and snow and sleet. I knelt in the grass and cried.

I cried for the goose and her eggs, but I cried, too, for the weight of things that don’t go the way they should; for all of the lives that come into this world carrying more of that weight than they ought to and that exist in a more dangerous world than the one you will because of it; for our failure to share and ease that burden or to make this world safer for all; and for the sometimes unbearable uncertainty that claims so much, even the quiet eggs in a bird’s nest, here on a small pond.

A close family friend died suddenly several weeks ago, not from COVID but from a fall and then a heart attack. He lived in Oklahoma, where I grew up. It doesn’t feel safe enough to travel to the funeral. We didn’t get to say good-bye. I wrote a letter to his family—a gesture that felt utterly inadequate. I keep seeing his face, failing to remember that he will not be there the next time we go back to visit.

I’ve been coming back to a line from a sermon that a friend of mine gave to her Unitarian Universalist congregation last year. She was speaking about how when her own daughter—now a teenager—was so small and so new, she would hold her and think, “This is as safe as I will get to keep you.”

I think this is the real root of my fear in imagining the world you will come into, from the moment of your birth: that this—these final weeks of pregnancy—is as safe as I will get to keep you, here in my womb, where you are warm and protected. Shielded.

Daughter, the world out here is so beautiful and so fraught. Your father and I have many conversations about how to raise you to watch geese and plant seeds and eat apples off the tree and listen to birds. How to raise you to respect and hold space for others who are different from you, how to be aware of and address the privilege that will come with your white skin as we continue to educate ourselves about our own privilege and complicity. We talk about how to raise you to be a listener, especially to those whose voices have routinely been silenced or dismissed—human and non—and the richness that listening brings.

When I start to feel fear creeping in—when I start to think about what it will mean to labor in a face mask, to quarantine with you for several weeks after you’re born, without visits from our parents and other family members, and from there to navigate a pandemic with an infant; when I smell the emissions from the oil tanks up the road from a company that has routinely flouted EPA emissions caps; when I read reports on how quickly the Gulf of Maine is warming—

—then I try to remember that the goldfinch this morning knew just where to land on a tall blade of grass so that the grass would bend just so, just enough to hold his weight a few inches above the ground, and how this bright little bird stayed balanced on the grass for a long moment, and when he departed, the grass righted itself again and the bird was gone in a flash of yellow in the mist.

I try to remember that my body knows what to do to bring you into the world. The goldfinch knows what to do. And the goose and the apple tree. And there are so many in the world who know to listen deeply, who are working to heal wounds. Humans, too, know how to do this work.

So, Daughter, I eagerly await your arrival. I imagine how you will look and smell and sound and how the world around you will be. We are preparing to introduce you to this world in all of its wonders and griefs, blessings and faults, where the songs of birds are so beautiful and the unexpected is there, always, to impart its lessons.