New Life in Spring

Pregnancy and the Coronavirus

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

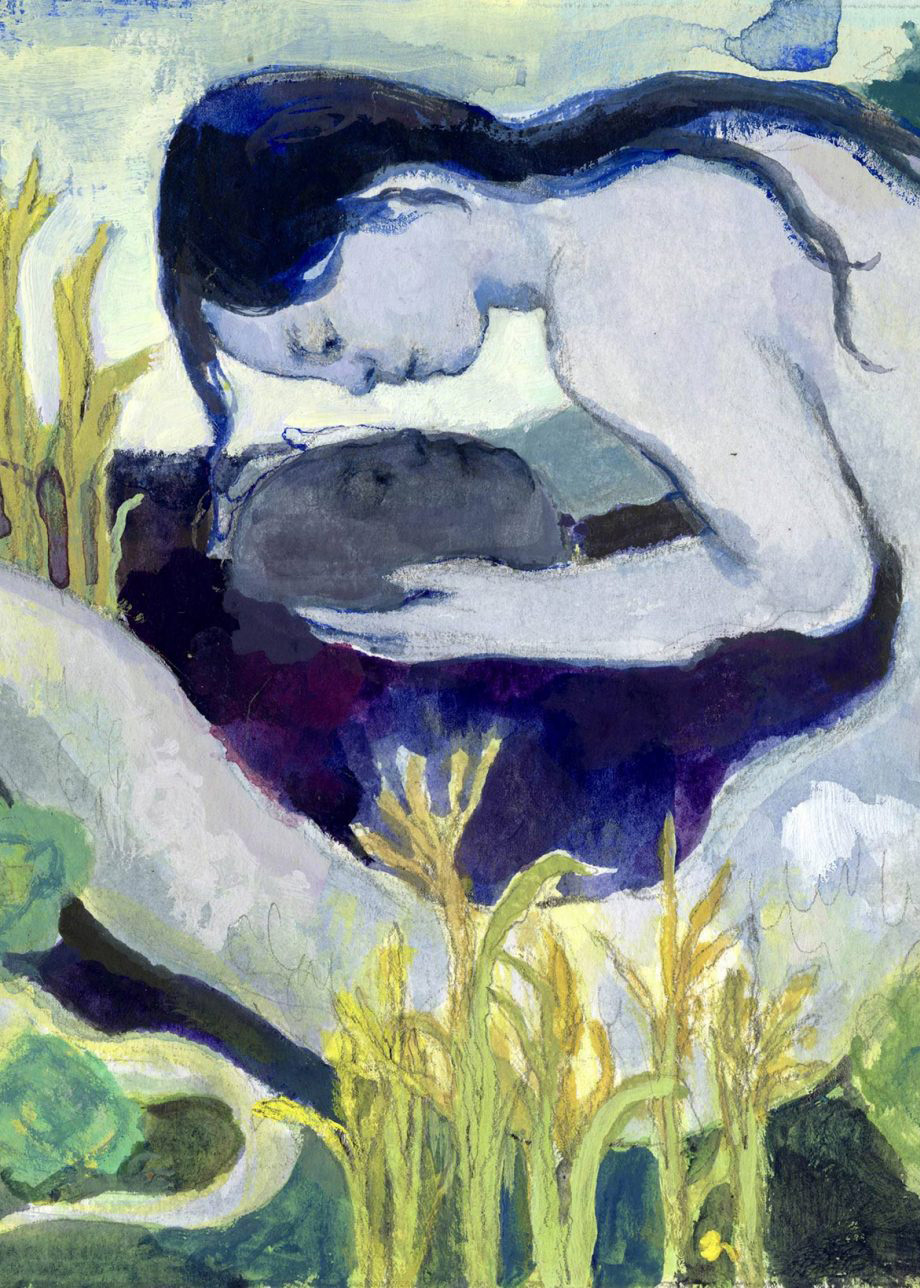

Holding a spring bud in her hand and new life in her body, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder navigates the blurred lines between uncertainty, vulnerability, and joy.

Each year when the last of the snow has melted, I begin my ritual of walking circles around the yard in the mornings to see what is growing. A little over two weeks ago, I noticed that buds had appeared on the weeping cherry tree. This week, the dogwood, the apple tree, and the lilac have followed suit. Given the weather of late, they are all right on time: mid- to high forties at night and high fifties—even sixties—during the day. The sun shines down like a siren song beckoning the sap to run again through their veins and bringing signs of life to the tips of their branches.

Every morning since, as I make my rounds, pausing at each tree to examine the buds—fuzzy on the apple tree, elegant and scaled on the cherry, sharply pointed on the dogwood—I rejoice. And then I begin to worry.

I live in Maine, and when the cherry tree budded, the calendar had barely tipped from February into March. Too soon. This morning there are snow flurries in the air, and when I checked the trees a few minutes ago, they appeared unchanged to my untrained eye. But I wondered if they’d already been damaged. I closed a hand gently over a few of them, as if a temporary transfer of my own body warmth could make some sort of difference. The temperature dipped down into the twenties last night; it was eighteen degrees the night before.

I try not to worry. However many tree buds I manage to briefly cup in my palms, I will not change their fate this season. It will be what it is, I tell myself. Sometimes that helps.

Still, even on this cold morning in the snow, the sight of those buds prompts a bound of joy. And I never attempt to talk myself out of rejoicing.

It’s possible that I’ve been thinking so much about the budding trees because there is a baby growing in my belly; a new life that seems so tender and miraculous that it makes me catch my breath. For a time in the early weeks of my pregnancy, this life was a secret, both quiet and jubilant, between my husband and me. Fifteen weeks in, this presence has made itself outwardly known. I recently attended a school event for my husband, and one of the teachers he works with approached him afterward and whispered, “Chelsea’s pregnant!” It wasn’t a question.

It’s too early to feel any kicking or wriggling, but if I sit still, I can feel this new life inside of me. Something I can only describe as an energy, an expanding light. In such moments, rejoicing seems the only response I am capable of.

But when I bring my attention back to the world, there is an unmistakable sheen of worry. It’s been five days since my husband’s school event, and the world has changed. He is now teaching from home. My brother is “indefinitely” out of a job and a paycheck at the restaurant where he’s been working for several years. We canceled our trip to visit my grandmother in Nebraska. With predictions of hospitals running out of space, we breathed a sigh of relief that a close family friend who recently had a heart attack will be able to keep his scheduled date for coronary bypass surgery.

None of these things were questions in February. We were passing our phones around to anyone who would ask to see a picture of my first ultrasound.

Then, I was trying not to touch my phone—much less my face—if I was in public.

Now, I try not to be in public.

In the best of conditions, pregnancy is a vulnerable time. There is a long list of things you shouldn’t do, shouldn’t drink, shouldn’t eat. This being our first child, we are doing our best to keep up with a growing stack of books and articles, learning as we go about the stages of development of a fetus, keeping up with the numerous appointments on our calendars, deciding which optional tests to have done, seeking advice about birth plans. My body is changing—my weight, my energy level, my ability to focus, my appetite, my mood—often with little discernible pattern or consistency.

Until now, in the midst of all of this change, there has been useful information readily available. Our questions have generally had answers, in part because many aspects of pregnancy are well-charted territory, and in part because I am fortunate so far to have had an uncomplicated pregnancy, where the standard answers and expectations tend to apply. The very fact that vulnerability is expected and normal for pregnant women has meant that I can reach out to family and friends who have children for advice and comfort, and thus a sense of safety.

There are few answers, expectations, or comforting words when it comes to COVID-19. Two studies indicate that the virus is not passed from mother to child just before or during birth—good news. But those studies have involved just nine and four mothers, respectively.

And so, the line between joy and worry, vulnerability and safety, becomes blurred and confused. One follows the other follows the other. The trees are budding and beautiful, and it is snowing outside; my child is growing in my belly, and the world is screeching to a halt. I am having trouble locating the difference between common sense and paranoia.

We saw our obstetrician yesterday, and I hoped she would tell us with confident expertise that our social distancing measures were likely to work, that by taking extra precautions we had a good chance of riding out the storm and staying perfectly healthy. She didn’t. Instead she told us that social distancing is just to keep the hospitals from getting overwhelmed. “You should prepare for the fact that you will likely get the virus in the next twelve months,” she said. “And you will likely be just fine. The latest information suggests that there’s no indication that pregnant women have any higher chance of complications or death.”

My husband and I sat there somewhat stunned. I couldn’t tell if I felt better or worse. I hadn’t truly considered the possibility that we could do everything right—for the sake of our new child, for ourselves, for the most vulnerable members of our community—and it might not make much difference in terms of, at the very least, our chances of getting sick.

Then she asked, “Do you want to hear the heartbeat?”

And there, as I was lying on the table, the worry dissipated completely for a long moment. All I could hear, at 156 beats per minute, was joy, joy, joy.