The goddess Durga stands as a protector at Bhuna Bai ji ka Oran—a sacred grove in central Rajasthan.

One Hundred and Eleven Trees

Photos by Diane Barker

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

Diane Barker is a photographer and artist, based in Worcestershire in England. For the past twenty-five years, her work has focused on the Tibetan people and, in particular, Tibetan nomads. Diane has shown her work extensively around the UK, as well as in India and New York, and has work in private and public collections around the world.

When a marble mine began to strip a village of its forests, the people of Piplantri, India, developed a tree-planting project that reclaims a vital and ancient relationship between trees and women.

1 Goddess of wild and forest who seems to vanish from sight.

अरण्यान्यरण्यान्यसौ या परेव नश्यसि

How is it that you seek not the village? Are you not afraid?

कथाग्रामं न पर्छसि न तवा भीरिव विन्दती.अ.अ.अन

2 What time the grasshopper replies and swells the shrill cicala’s voice,

वर्षारवाय वदते यदुपावति चिच्चिकः

Seeming to sound with tinkling bells, the Lady of the Wood exults.

आघाटिभिरिवधावयन्नरण्यानिर्महीयते

3 And, yonder, cattle seem to graze, what seems a dwelling-place appears:

उत गाव इवादन्त्युत वेश्मेव दर्श्यते

Or else at eve the Lady of the Forest seems to free the wains.

उतो अरण्यानिःसायं शकटीरिव सर्जति

4 Here one is calling to his cow, another there has felled a tree:

गामङगैष आ हवयति दार्वङगैषो अपावधीत

At eve the dweller in the wood fancies that somebody has screamed.

वसन्नरण्यान्यां सायमक्रुक्षदिति मन्यते

5 The Goddess never slays, unless some murderous enemy approach.

न वा अरण्यानिर्हन्त्यन्यश्चेन नाभिगछति

Man eats of savory fruit and then takes, even as he wills, his rest.

सवादोःफलस्य जग्ध्वाय यथाकामं नि पद्यते

6 Now have I praised the Forest Queen, sweet-scented, redolent of balm,

आञ्जनगन्धिं सुरभिं बह्वन्नामक्र्षीवलाम

The Mother of all sylvan things, who tills not but has stores of food.

पराहम्म्र्गाणां मातरमरण्यानिमशंसिषम

—Rig Veda, Book 10, Hymn CXLVI. Aranyānī1

The Indian subcontinent was once a vast sea of green forest intersected by the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra rivers, whose waters ran down from the high mountains, weaving and running through the trees.

Many of these primeval forests have been severely depleted or have entirely disappeared in the last three hundred years. After the arrival of the East India Company in 1757, the British Empire began seizing land to create a “commons,” a way to bring India’s natural resources under state rule, which permitted vast tracts of forest to be cleared for timber, railways, and agriculture. After India’s independence in 1947, the new government launched a process of economic expansion and rapid development. More trees were felled to make way for industrial projects, farming, grazing, and mines.

Through it all, rural communities in India have protected small groves of trees: evergreen forests in the Western Ghats, tropical jungle in the south, desert shrubland and Himalayan forests in the north. India’s forest dwellers are mostly tribal people who are indigenous to the subcontinent, referred to as “scheduled tribes” within India. Though the areas around their groves may have been widely cleared, these communities have kept small pockets of green safe from felling and other forms of environmental destruction. These increasingly isolated pockets of forest are often sources of both food and livelihood. Today, one-fifth of India’s population—approximately 275 million people, most of whom live on fewer than two dollars a day—relies on forests for clean water, wood for fuel, fodder for livestock, and timber. Some rural forest dwellers receive as much as half of their daily caloric intake directly from forested areas.

But the people who live among these groves do not merely see them as sustainably managed practical resources: communities relate to these groves as sacred and as the abode of local deities.

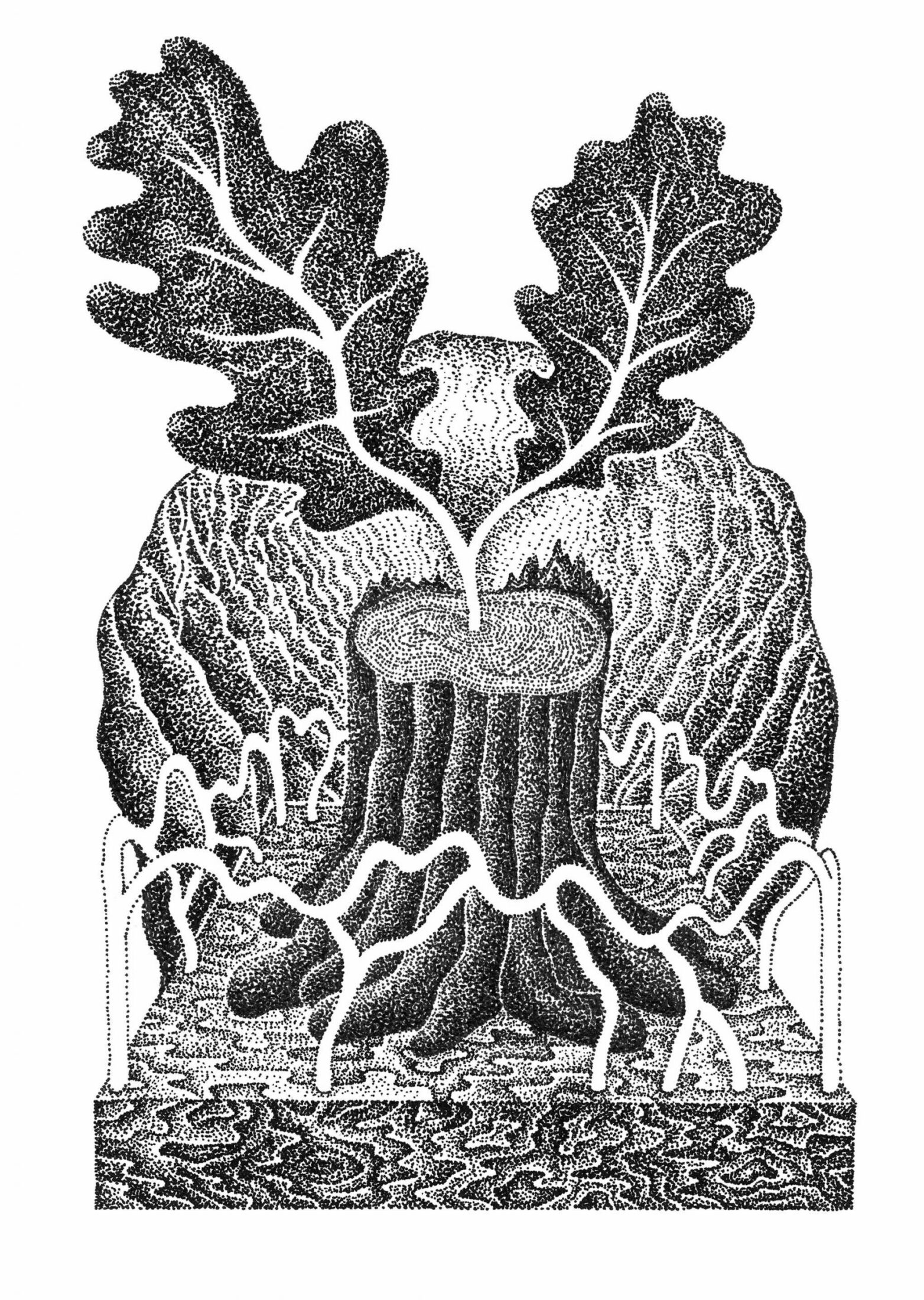

For thousands of years in India, trees have been entwined with divinity—a relationship that permeates Hindu mythology. The peepal tree—Ficus religiosa, sacred fig—is the tree of creation. A broadleaf evergreen native to India, it is known as the dwelling place of the trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh. (This tree holds a deep significance in Buddhism as well—known also as the Bo tree and Bodhi tree—it is the tree the Buddha sat beneath when he reached enlightenment.) The peepal is an epiphyte: if a seed is deposited (by a bird, perhaps) in one of the tree’s upper crevices, it can germinate and send out roots that grow to the ground from above, take hold in the soil, and become new trunks. In Hindu mythology, the peepal, also referred to by the name Ashwattha, is often depicted upside-down, with its roots stretching into the heavens and the branches of its crown reaching toward the earth. The fifteenth chapter of the Bhagavad Gita opens with the lines: “With its original source above (in the Eternal), its branches stretching below, the Ashwattha is said to be eternal and imperishable; the leaves of it are the hymns of the Veda.”

There is also the neem, Azadirachta indica, with its lush crown of narrow leaves, which is inhabited by Shitalā, the goddess of smallpox. It is a healing tree, sought for its curative properties. Lord Krishna played a flute made of green bamboo, whose name in Sanskrit, vansh, means “clan.” There is the banyan, Ficus benghalensis, with its many trunks, the tree of immortality; mango, Mangifera indica, whose branches are used in sacrificial rights; bael, Aegle marmelos, associated with Lord Shiva; and amla, Phyllanthus emblica, whose fruits are divine medicine.

Often, these protected sacred groves surround a temple, and following local spiritual traditions, the community takes from them only what is needed for firewood or food. The protection of these forests has, in turn, helped to protect local sources of water and places where diverse species find needed refuge.

In the last twenty years, India has lost as much as 1.5 million hectares of tree cover to agriculture, development, and industry. The sacred groves are increasingly isolated. And the whisperings of industry are there, moving closer to the forest’s edge, wondering how much these sacred trees are worth.

A banyan tree at the Bhuna Bai ji ka Oran grove.

Within India, much of the religious and cultural recognition of the divinity of trees pertains to trees’ relationship to women. “The tree-woman relationship dominates Indian myth,” writes Kapila Vatsyayan, a leading cultural scholar of India. “The most functionally meaningful and inspirer of countless myths and the richest treasure of Indian sculptural motif is the Vrishkika, also called by other names—Yakshi, Sursundari and many others. They stand against trees, embrace them and thus become an aspect of the tree articulating the interpretation of the plant and the human. The tree is dependent upon the woman for its fertility as is the woman on the tree.”2

The Bishnoi—a sect of Vishnu worshippers—was founded in Rajasthan by a sage named Jambheshwar in 1485 following his apocalyptic vision of humanity’s destruction of nature. Located throughout the state, the Bishnoi take the protection of forests and the wildlife within them as the crux of their religious tradition. They forbid cutting green trees, carefully manage grazing, and extend the rule of taking no life all the way down to insects.

The most revered and devastating story of the Bishnoi and their trees occurred in the year 1730, when the women from the village of Khejarli in Jodhpur district heard that the king of Jodhpur planned to fell their sacred Khejri trees. When the king’s soldiers arrived to carry out their orders, four women wrapped their arms around the trunks of trees and refused to let go. The king’s soldiers beheaded them, along with another 359 members of the village who followed the women’s example. And then they felled the trees. The king was so distraught upon receiving word of the community’s fate that he forbade any further cutting of trees in Bishnoi territory.

Though the vast majority of Rajasthanis today are not as explicitly ecological in their beliefs and actions as the Bishnoi, the existence of hundreds of sacred groves in the state—the abodes of as many deities—is evidence of a widespread recognition of forests as an embodiment of the Divine.

Located in the northwest corner of the subcontinent, Rajasthan is India’s largest state by land area, though it is relatively small and sparse in terms of population, with just 68 million people (compared with Uttar Pradesh’s population of nearly 230 million). Before India achieved its independence from the United Kingdom in 1947, Rajasthan was divided into two dozen princely states, all of which were slowly consolidated into a unified India post-independence.

To the southeast of Rajasthan’s great Thar Desert lies a curving band of green hills that run northeast across the state. At over one billion years old, the Aravalli Range is one of India’s oldest. While the Himalayas continue to rise to the north, the tectonic plates beneath the Aravalli hills have long ceased their collision, leaving these ancient mountains to weather and erode. The highest peak, Mount Abu, reaches a height of 5,600 feet, and most of the Aravalli hills are several thousand feet lower still.

To the northwest of the Aravalli Range, the climate is arid and largely unproductive, and the land becomes entirely barren once it reaches the sand dunes that lie at the heart of the Thar. The areas to the south of the range are more fertile and benefit from the range’s watershed, which gives an eastern flow to Rajasthan’s only major perennial river, the Chambal.

More than half of Rajasthan is covered by sandy plains with shrubland ecosystems that consist of drought-resistant trees and sparse grasslands. Less than 10 percent of land in the state is covered in trees. Scattered forests are found primarily in the Aravalli hills and constitute critical habitat for tigers, leopards, sloth bears, and sambar.

Within and between Rajasthan’s scarce forests are 560 known locations of sacred groves. The majority of them are made up of fewer than one hundred acres of land; many cover far fewer than ten acres. Filled with cutch tree, Indian mesquite, myrrh, salvia, neem, Indian plum, banyan, and peepal, almost all of the groves house either a shrine or a temple.

Many of these groves can be found within the Aravalli hills. Five kilometers outside the pink city of Jaipur in east-central Rajasthan, nestled in the center of these green hills, is the sacred Bheru ji Ki Bani grove. The grove and its temple are housed within a forest that is protected as a leopard preserve. While the narrow dirt road that winds through the trees does not offer a sighting of these great cats, a sense of their presence follows the road in the form of a high chain-link fence that runs unbreaking on either side. Monkeys look down from the trees; black hogs rummage along the roadside.

The road leads to a sixteen-hundred-year-old temple at the preserve’s center, where a bell is ringing. Several dozen newly planted saplings rise from the sandy soil, each protected by a metal cylinder around its trunk. Nearby, a man is pouring an offering of rum onto the base of a much older and well-established tree whose trunk has been wound with red thread, the branches draped with blue and gold and purple cloth. A flock of pigeons rises into the trees and descends back to the ground, again and again. A woman is sweeping the petals of yellow and red flowers from a marble floor. Out beyond the fence, the peacocks are calling into the hills, fanning their great tails.

Two hours further south, past small farming communities, tiny villages, and water buffalo basking in the temporary ponds delivered by the monsoon, lies the Bhuna Bai ji ka Oran grove in Rajasthan’s Ajmer district. Here is the place where a woman, for whom the grove is named, achieved enlightenment and then protected the villagers from the ill effects of a demon.

The feminine is often at the center of sacred groves. In her book Belief, Bounty, and Beauty: Rituals Around Sacred Trees in India, Albertina Nugteren writes:

The deity or deities worshipped [in a sacred grove] may be male or female, but female deities appear to be in the majority, being local representatives of wood spirits, earth-mothers, clan-mothers, fertility goddesses, and snake-deities. [Others have made] an explicit connection between the goddesses of the sacred groves and the Vedic goddess Āraṇyanī, the lady of the forest who is praised as the mother of all beings … She is often seen as some form of Bhagavatī or Bhadrakālī, known by such names as Amma(n), Mariamman, Devi, Durga, Sitala, and Gauri.3

At the Bhuna Bai grove’s entrance, a wide circle of stone and plaster has been built around the trunk of a banyan tree. A statue of the goddess Durga stands in front of it. With her eight arms and her foot resting on a lotus flower, she sits atop a lion. Durga embodies the shakti, the feminine power, that protects followers from evil and keeps them safe from harm.

Past the goddess, a steep set of stone stairs leads up to the temple building, which is in the final stages of construction. Around it, green and pink flowers are blooming; the cacti stand six feet tall. With the welcome growl of thunder in the sky, the temple grounds are quiet. Beneath the gray clouds, the hills that reach far beyond look all the more green in the dim light.

Devnarayan ji ki Bani—a sacred grove in Rajsamand district, Rajasthan.

Nearly three hundred kilometers southwest of the Bhuna Bai grove, in Rajasthan’s Rajsamand district near the southern end of the Aravalli Range, there is a different low rumble in the air, coming not from the sky, but from the earth: blasts from sticks of dynamite.

India is one of the world’s largest producers of raw stone. The country’s growing mining industry has excavated thousands of mines, many of which are run by companies that have carved out territory in previously untouched rural areas.

Rajasthan contains the vast majority of India’s marble, used most famously in the building of the Taj Mahal. Throughout their range, the Aravalli hills are known to be rich in marble, sandstone, granite, and zinc. The mining industry has dismantled an estimated 25 percent of the Aravalli Range since the late 1960s. The marble industry has brought several mines to the district of Rajsamand—and thus to the doorsteps of previously quiet and isolated communities, like the village of Piplantri.

When Shyam Sunder Paliwal was growing up, he and his family lived near the top of one of the Aravalli’s low hills, just outside the center of Piplantri. Shyam’s family had long been farmers, growing most of their food for subsistence and some to sell in the local markets. When he was a child, the branches of Piplantri’s trees were filled with birds, and Shyam would occasionally encounter leopards roaming along the dusty roads. Once, he and his grandmother witnessed a tiger taking one of their cows, and his grandmother warned him not to cry out. There was little distinction between the village and the jungle; the landscape was green and filled with wildlife.

When Shyam was a teenager, marble was discovered beneath his family’s home.

The mine company had already acquired enough property to begin their excavation, but they gave Shyam and his family a choice: keep their home and stay where they were and thus be exposed to constant noise, the known dangers of inhaling marble dust, and contaminated water; or sell. They sold, as did the other families nearby.

“Because of the marble blasting, there was so much dust in the house, which could [have] caused many diseases. So we had to leave,” says Shyam. “It’s still very painful.” Some families moved into the center of the village and found new land to farm; many others went to work in the mines.

The industrial saws used to cut marble can require as much as forty-five thousand liters of water per hour. As the marble is processed and polished, the waste is transported away from the site in the form of a slurry: water mixed with fine particles of stone, which contaminates soils. Thus, the mine drew much of the local water from the ground, lowering the water table. And with no roots left to hold water in the soil, rainwater would run down the hills out of reach.

As he grew up, Shyam witnessed his village quite literally drying up. Trees disappeared. Wildlife and birds retreated to the jungle beyond. Farmers and their crops suffered. Eventually, people began to leave the village, no longer able to farm, or sought better working conditions than could be offered in the mine. Those who remained often had little water that was safe to drink.

People in the village had long been cutting down trees for firewood or to make coal, but as the mine brought jobs to the village and more opportunity for profit, the population rose, as did the need for trees and the land on which they grew. As the mine expanded its operations, previously forested areas became covered with mounds of debris and waste. Some of these slag heaps, which are prone to sliding, are now as tall as the native hills that surround them and cover land that was meant to be held in common for the people to live on and farm.

Workers pause to look into the depths of the RK Marble mine outside the village of Piplantri.

As an adult, Shyam was elected sarpanch, or mayor, of Piplantri. He was intent on improving conditions in the village to counteract the destruction of the mine. As the hole in the mountainside continued to widen on one side of the village, Shyam, now a father of three, helped to create irrigation systems in the village center, and plumbing to improve sanitation. He built a well to hold water in a centralized place and encouraged the farmers to build terraced fields for growing their crops so they could better capture the water on the hillsides.

Conditions in the village began to improve. And though people were still felling trees and the blasts from the mine were echoing through the village streets over the course of every day, Shyam felt as though he was making a difference.

The focus of Shyam’s efforts shifted unexpectedly and dramatically in 2006 when his sixteen-year-old daughter, Kiran, fell ill. Before the family could seek help in the city, she died from heat stroke and dehydration.

Filled with grief from the loss of his daughter and bewildered by the suddenness of her death, Shyam began to realize something else was wrong in the village, something apart from the mines, apart from the water loss and the deforestation—something which he had not yet been able to fully see. For the first time, Shyam looked around and began to realize the extent to which girls and women in his community were invisible. Though India had begun to create space for women as social, economic, and political leaders, this was not apparent to Shyam as he walked the streets of Piplantri; rather, he saw a more common narrative of absence.

Girls and women in the village could not ride bicycles or go to college. They did not publicly participate in village life or in any decisions that were made. They could not earn their own money and could only venture outdoors with their faces covered, and even then, only with the permission of their families and husbands. In small villages like Piplantri, where people are poor and resources are scarce, the dowry that a family is expected to pay when a daughter gets married can, in some cases, create a financial burden that the family may not recover from. And it is often the girls, therefore, who are perceived as the burden.

Within Piplantri, girls were not required, nor often expected, to complete their education. In Rajasthan and in many places across India, aborting female fetuses and female infanticide have not been uncommon—painful, dark truths, too daunting and deeply rooted for one person to address.

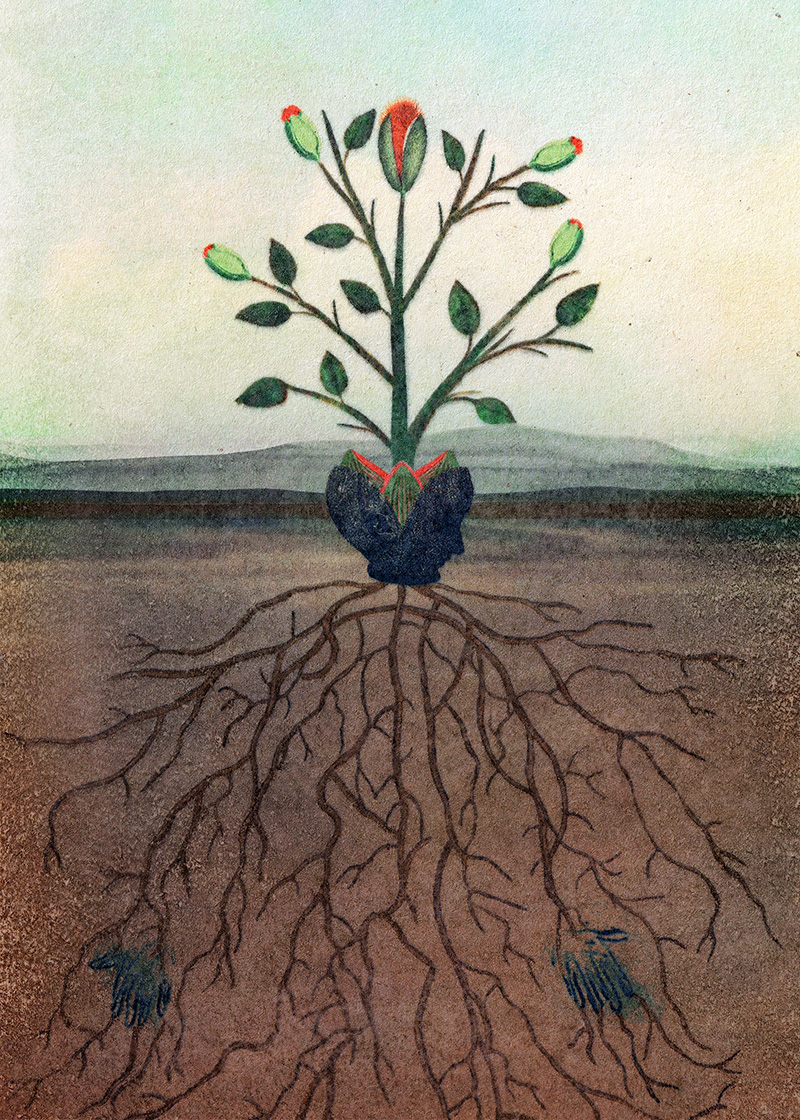

But beneath the excavations into the earth that were draining away the water in the village and tearing open the hills; beneath the long-standing, rampant dismissal of the importance of girls and women, there was an ancient tradition from before the time when the Vedas were written down: a current of cultural memory that still held and recognized the vital, fertile, living connection between women, trees, and the earth.

11 O Prithivī, auspicious be thy woodlands, auspicious be thy hills and snow-clad mountains.…

12 … I am the son of Earth, Earth is my Mother.…

13 Earth on whose surface they enclose the altar, and all-performers spin the thread of worship;

In whom the stakes of sacrifice, resplendent, are fixed and raised on high before the oblation, may she, this Earth, prospering, make us prosper.4

To honor Kiran’s memory, Shyam planted a burflower, or kadam, tree. The kadam is widely revered for its medicinal properties and is associated with one of the twenty-seven stars that make up the main pantheon in Hindu astronomy. He encouraged other villagers to plant trees for her as well, and a small grove soon took root around the burflower. As the grove expanded, the villagers understood that these trees should be protected, that no one should cut them down. People acknowledged the meaning in them.

Shyam stands with a tree that bears a photograph of his daughter Kiran.

“I thought that if they all cared [about these trees], then they should [plant trees] for all of their daughters,” says Shyam. “But they quickly forgot.” Village life soon went back to normal. People continued to cut the village’s other trees, and the standing of girls and women remained diminished. But Shyam kept his vision alive—if the village planted a grove of trees for every girl, things would somehow change.

He spoke to several women in the village who he thought would be receptive to his idea.

“I came to the village after my marriage,” recalls Kala, a direct, light-hearted woman, quick to poke gentle fun. “I wasn’t allowed to leave my house, unless it was to take care of the cows or to look after my children.” Kala had married a man from Piplantri and moved to his family’s home. “There was a lot of destruction because of the mines … there were no animals here … And the people in the village wanted boys. If anyone had girls, they would be very sad and disappointed.” Kala was raising two young daughters.

Shyam’s thought was to ask the villagers to plant 111 trees every time a daughter was born: 111 because “one” is a sacred number in Hinduism, and because three “ones” coming together constitutes a community.

When he arrived at Kala’s door and asked her to be involved in the tree planting project, she said yes. For the first time, Kala and the other women in Piplantri were invited to attend and participate in meetings. They were offered paying jobs. Shyam asked for their help in reaching out to families, planting the trees, and building fences around the new planting areas. Many of their husbands were opposed to the project and were particularly against their wives’ employment, but with the blessing of Shyam, the village sarpanch, the women ventured out and began the work that would come to define their independence.

When a baby girl was born, this group of women went to the girl’s family and helped them to acquire and plant the young trees. Shyam began to receive small grants to provide the families with saplings. Some families donated their own money.

“This project called us out of our houses,” says Kantu, sitting with her grandson in her lap. “It took a long time to stop being afraid of going out. At first, we would hide on our way to work. Now we’re not afraid of anyone. We belong to the same village.”

Parvati and her daughters, Puja and Nikita, have come to water the trees that Parvati planted.

Parvati stands with one of the trees that she planted for her daughter Nikita.

Piplantri is surrounded by the green hills of the Aravalli Range. In this small rural community, people get most of their food from local and neighboring farms. Many still cook over open flame. Life, in many ways, remains traditional and formal.

But for thirteen years, the village has been planting 111 trees every time a baby girl is born. Papaya, mango, neem, burflower, banyan, peepal, bamboo, and other species. To participate in the project, families must sign an affidavit that promises their daughters will care for their trees, will complete school, and will not be allowed to marry until the age of eighteen. In exchange, every daughter is given a stipend of thirty-one thousand rupees—either raised by the family or, increasingly, given through sponsors and grants—enough for either a dowry or college.

Dipika Paliwal, fifteen years old, attends the Piplantri village school in the center of town. She wears two French braids that fall behind her shoulders and a beige school uniform. She has excellent posture and a frank gaze.

“Trees give us oxygen. They give us fruit. They make the world more beautiful,” she says. “Earlier, because of the mines, there was a lot of destruction in the village; there was a lot of dust. After this initiative, the whole village is turning green.”

Shyam estimates that two hundred thousand trees have been planted. Every year, families across India celebrate Raksha Bandhan—a holiday in which sisters tie rakhi, cloth bracelets, around their brothers’ wrists as a symbol of familial love and unity. The girls of Piplantri follow this tradition along with the rest of the country, but they also tie bracelets around the trunks of their trees.

Dipika’s mother planted trees for her when she was three years old, as the project was getting started. “My mother planted those trees, and my mother also gave birth to me, so according to that, the trees are my brothers. Every year, I go there and tie rakhi, and I pledge to protect the trees. In return, the trees also protect me.” As the girls grow up, they are responsible for taking care of their growing trees. Several times a month, Dipika waters her trees; she harvests their fruit and checks to make sure no one is taking any of the wood.

Sisters Deepika and Seema Prajapat perform the rakhi ceremony, tying colorful bracelets around the trunk of a tree and making offerings of rice, coconut, and sindoor.

Girls practice yoga in class.

Girls are attending school now at the same rate as boys. Many intend to go to college. As part of their curriculum, the schools in the village teach the children about the project and the importance of trees. Anita, thirteen years old, wants to be a doctor when she grows up. “In our honor the trees are planted, so we feel like there’s something we [can do] in their honor. We feel proud of that.”

Wildlife is returning to the village. Birds are in the trees. Visitors are warned not to venture too far on the dirt paths that lead into the hills: leopards and panthers have been seen in the vicinity.

People have started coming back to the village from the city, or are choosing to stay. Jutsna, a woman in her mid-twenties, married a man from Piplantri and moved to the village from Rajsamand. Usually, she tells me, women are unhappy if they marry into a rural village and have to leave the city. But she says she is proud to live here. Four years ago, she planted trees for her daughter, Daksheeneh. “When we go to the trees,” she says, “Daksheeneh plays with the trees and the birds. I hope for my daughter that whatever she wants to become, she can be.”

The project employs an average of forty people from the village. Kala now runs a women’s group that plants aloe vera around the trunks of the trees to ward off termites. The women then harvest the aloe and make lotions, shampoo, and face wash to sell. They keep the profits for themselves and set aside a pool of money to give to any woman who needs a loan. In the meantime, their daughters are being raised at home and in the schools to understand the importance of trees and the importance of their role in caring for them. The headmaster at the primary school says, “Girls are the most powerful people in the world. They are no longer a burden to their families. They can do anything.”

“My mother planted those trees, and my mother also gave birth to me, so according to that, the trees are my brothers.”

In the nearby city of Rajsamand, the roads are lined with businesses selling white marble—miles and miles of disassembled mountains and hillsides, stacked neatly along the pavement in polished squares or carved into statues.

The RK Marble mine has been operating for thirty-five years and is estimated to have several decades of excavation left, which will likely bring the mine closer to the village center. The mountain is now inside-out and exposed; one climbs hundreds of meters down it, into the earth.

Shyam’s family’s old home now stands at the brink of the chasm. The roof is gone; small trees and shrubs are growing out of the floor; pigeons are nesting in holes in the walls. The ceaseless roar outside heightens for brief moments with the sound of blasts in the rock far below, or when a straining truck whose bed is loaded with stone rumbles by.

The house directly across from Shyam’s still stands but is bare and crumbling. A security guard lives here. He works twelve hours a day, seven days a week, for the equivalent of five dollars a day, or forty-one cents an hour. Many of the village’s men continue to work in the mines or sell marble at the stands along the road in the city. It is still one of the few available ways to make money to support a family.

Rajasthan has the highest number of mine leases in India: 1,324 for major minerals, 10,851 for minor minerals, and 19,251 for stone. In the course of just a few decades, large swaths of the Aravalli Range have been hollowed out or turned to rubble, the rivers that run down the mountains have been inundated with slurry, soil erosion is rampant, and the water table is lowering.

Many of the mines and quarries operate with little accountability for the environmental destruction that comes in their wake and its toll on human health. The Indian government is struggling to both stop the rise of illegal mining—largely controlled by the mafia—and effectively regulate and oversee the mining that has been permitted.

Since the 1980s, the national government of India has made several widely well-received attempts to mitigate the environmental impact of a rapidly growing industry and population. India’s National Forest Policy of 1988 acknowledged that:

Over the years, forests in the country have suffered serious depletion. This is attributable to relentless pressures arising from ever-increasing demand for fuel-wood, fodder, and timber; inadequacy of protection measures; diversion of forest lands to non-forest uses without ensuring compensatory afforestation and essential environmental safeguards; and the tendency to look upon forests as a revenue earning resource.

This policy was passed and was generally lauded for its outlining of protections for India’s dwindling forests. According to the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change, the act was intended “to ensure environmental stability and maintenance of ecological balance, including atmospheric equilibrium which are vital for sustenance of all life forms, human, animal, and plant.”

The 2006 Forest Rights Act subsequently recognized the rights of rural forest-dwelling communities to legally participate in the protection of their forests:

Whereas it has become necessary to address the long-standing insecurity of tenurial and access rights of forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers, including those who were forced to relocate their dwelling due to State development interventions.

But in the last thirty years, fourteen thousand square kilometers of Indian forest have been cleared to make way for 23,716 industrial projects. Since the passing of the Forest Rights Act, less than 3 percent of community forests have been officially recognized. Now, the latest draft of the National Forest Policy, released in 2018, seeks to replace its 1988 counterpart. This new policy calls for a public-private partnership to meet the country’s growing demand for timber and has been widely criticized for its focus on “forest production” for the timber industry. The report largely fails to mention any role for traditional forest-dwelling communities.

Deforestation from industry continues to wreak havoc on ecosystems like the Aravalli hills and the communities that rely on their forests.

One of Piplantri’s few stores, on the way to the government school.

A woman in Piplantri prepares dinner over an open flame.

Piplantri and the mine coexist in an uneasy relationship. The mine donates funds to the tree planting project. The floors of the new guest houses are built of huge slabs of white marble. One of the women who cooks food for the visiting guests who come to see the tree planting project lost her husband to silicosis, a respiratory disease caused by inhaling marble dust. This is not uncommon.

The owners of the mine use their participation in the project to advertise their dedication to environmental stewardship. They’ve planted trees on some of the slag heaps, and so these false mountains made of rubble that sit at the edge of the village now bear scatterings of green.

Shyam and his family entered the marble business themselves many years ago—they own a small marble trading business in Rajsamand. Though he is no longer sarpanch, Shyam is spending the vast majority of his time in Piplantri working on the tree project, and less and less running the family business. But he courts the sponsorship and support of the mines.

His son, Rahul, is expected to move to Rajsamand and take over the family business when he’s old enough. But Rahul has been helping his father in Piplantri, and he wants to stay in the village and find a way to make the trees project more self-sustaining.

Shyam seems to anticipate that it will be difficult for some to not see their cooperation with the mines as complicit and counterproductive, even hypocritical. But, at least for now, the tree planting project can only employ so many people, and even then, they cannot pay as well as the mines do. The people are very poor; they are afforded little choice in how they make their living.

Shyam has managed to stake a stand that is practical and still idealistic. “We have understood that there is no point fighting with [the mines], or arguing with them,” he says. “[We just let] it happen the way it is going, so that we can compensate the loss by doing what we are doing here … It saves our energy … Earlier, we used to fight a lot and stand against them, but there was no point in doing that … They are making destruction; we are covering that loss. We can work that way … Maybe this example will transform their hearts.”

“They are making destruction; we are covering that loss … Maybe this example will transform their hearts.”

In the early morning of August 13, women begin to arrive at a cluster of buildings set in the midst of hundreds and hundreds of trees. These were constructed recently to serve as a central location for the project to host visitors and guests. The story of Piplantri’s tree project has begun to get national and international attention. It is monsoon season, and the day is growing hot and humid. The appearance of the sun promises to make the day even hotter, but everyone is relieved to see it. It’s been raining for several days.

The women are dressed in reds and oranges and yellows. And in their arms they are carrying their daughters who were born within the last year. Today is the annual tree planting ceremony, in which families bring their baby girls—an average of sixty are born every year—to plant their first tree.

Women process with their daughters atop their heads to the site where the girls’ first trees will be planted.

The women lay their daughters in wicker baskets, lined with red cloth and set in the shade, as the men play music, wrap each other in orange turbans, and smudge each other’s foreheads with sindoor, a red powder. As the drums beat faster and faster, one man is possessed by Vandevi, the village deity, goddess of the jungle. He hands a blunt sword to another man who strikes him repeatedly on the back. He is unscathed; the goddess has made him invincible.

As the infant girls wriggle and stare up from their baskets at the trees overhead, Shyam moves down the line of mothers and drapes a scarf over each of their necks. He gives a speech. An official from the local government and his family have come to witness the ceremony. He, too, stops to greet each of the mothers. There are dozens of cameras flashing behind him—journalists have come from within India and beyond to witness the occasion.

And then, the mothers rise. The men help them to place the baskets that cradle their daughters—a precious cargo—onto their heads, and together, accompanied by live music and chanting, everyone processes to the planting site. This year, all of the ceremonial first trees are to be planted near a new statue of Kiran, Shyam’s late daughter, which sits atop a fountain.

Each family is given one sapling. The holes have already been dug in preparation. The trees are placed into the ground, each with a sign that bears the daughter’s name and the date. The family will plant the remaining 110 trees in the coming year. The new saplings stand in the ground as the families gather for a shared meal and then carry their daughters home.

A girl sleeps in her basket as the day’s festivities carry on around her.

The next morning, Piplantri awakes to an overcast sky and brief, scattered showers. The girls are at home, preparing for the village’s unique celebration of Raksha Bandhan. They will celebrate this holiday in the traditional way tomorrow, along with the rest of India, but today, the girls—not the boys, they are very eager to clarify—get the day off from school. They get their hair done, don new dresses, and have henna painted on their hands. Today they will tie the rakhi, not around the wrists of their brothers, but around the trunks of their trees.

Girls have come not just from Piplantri but from the city of Rajsamand and surrounding villages. Even though many of them don’t have 111 trees, they want to participate in the celebration. They, too, have learned about it in school. Teachers have brought their female students.

And so, several hundred girls, dressed in their finest, giggling and beaming with excitement, arrive in Piplantri. In pairs, they’re handed a tray, fitted with sindoor, a coconut, rice, an apple, a banana, and the cloth bracelets.

All at once they disperse. They find a tree and make offerings with the fruit and the rice, and then tie the bracelets. When they’ve completed the ritual, they extend their right hands and recite a pledge, promising that they will not cut down trees, they will respect the environment, they will take care of the forests in the places where they live.

In witnessing the girls standing amongst the trees, one might hear the echoes of a hymn from the Atharva Veda, composed more than three thousand years ago:

13 … may she, this Earth, prospering, make us prosper.…

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16 In concert may these creatures yield us blessings. With honey of discourse, O Earth, endow me.

17 Kind, ever gracious be the Earth we tread on, the firm Earth,

Prithivī, borne up by Order, mother of plants and herbs, the all-producer.

18 A vast abode hast thou become, the Mighty. Great stress is on thee, press and agitation, but with unceasing care great Indra guards thee.

So make us shine, O Earth, us with the splendour of gold. Let no man look on us with hatred.5

The Village’s Treeplanting project is in many ways redemptive, in some ways fraught. The miners will continue to mine; they will almost certainly continue to be involved in funding the project and planting the trees. An uncertain and contradictory understanding will remain between the vast destruction on one side of the hills and the rejuvenation and care occurring on the other.

Indeed, much of what any of us do, even with our best intentions, is tied to extractive industry, and environmental destruction. There may not be a marble mine a few kilometers away, but somewhere our lives are tied to companies who are making a profit at the expense of the land and of the people who are trying to make ends meet by digging up the earth, felling forests, draining away the water.

The tree project continues to be largely run and managed by men.

Even so, something is shifting. At the Piplantri village school, a group of eight-year-old girls is rehearsing a song for an upcoming holiday concert. The lyrics say, “Girls are just like boys. You should not discriminate. We can do anything.”

The girls of Piplantri and the surrounding villages are growing up in a world that is vastly more open to them than it was even in their mothers’ generation. They are not only dreaming of but are expecting a life in which they are independent, making their own choices. And by caring for the trees that were planted to celebrate their entry into the world, they have become caretakers—for the ecosystem and for the future of their community, of which they have become an active part.

Planting trees in Piplantri has become a catalyst for change—perhaps further reaching than the man who started this project intended. It has sparked a transformation that goes deeper than the tearing apart of mountains—a transformation that is ever more held by the girls who grow up with the trees as their brothers.

Girls attend class at the Piplantri government school.

Dipika Paliwal, the girl with the frank gaze, has her hand painted with henna, an elaborate pattern. Her friend did it, she says proudly. On Raksha Bandhan, she went to the grove where Kiran’s burflower tree was planted. This is where Dipika’s mother planted trees for both her and her younger sister, alongside hundreds of others planted by other families.

The best way to protect the environment, she says, is “to get the people not to cut trees. The people who think the trees are useless—you need to educate them to know that trees are the most important thing.”

Dipika plans to go to college and become a teacher so that she can educate students from poor communities who don’t have access to education. She wants to make sure that girls like her in other villages are sent to school.

The money in her stipend will more than cover her college tuition.

Forty-five minutes away, in the neighboring village of Tasol, Anurandha Vaishnar is implementing many of the same projects as Piplantri. At twenty-three years old, she is her village’s youngest ever sarpanch (and she adds that she’s already been sarpanch for over four years). Though the office of sarpanch is still overwhelmingly held by males in regions throughout India, it is slowly becoming more common for women to be elected to the post. Anurandha spends her mornings at college, where she is studying geography, and returns home in the afternoons and evenings to tend to her projects in Tasol.

When Anurandha was growing up, her mother had to walk miles every day to collect water. She and the other women in the village would leave in the morning and not return until evening. “I would cry for my mother,” Anurandha says.

While the population of Tasol does not currently face any threat from mining, for many years the village was dealing with water scarcity and poor roads. Women had to cover their faces and could not attend meetings. Anurandha thought that if she were elected, not only would women be permitted to uncover, but, she hoped, they would also feel safe coming to her with their problems. This has proven true. She also hopes that her example will encourage the girls in her community to have confidence in seeking out an education.

In the meantime, she has started a water conservation project and has received enough money in government grants to equip every home with tap water. She is educating families about the importance of girls. And she is hiring women to plant trees. “I don’t want women to be dependent on their husbands,” she says through a translator. “I want them to reach their own independence.”

She looks at me and smiles.

“Girls are power,” she says in English.

- Rig Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith (1896), book 10, hymn 146. Modernized version accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Kapila Vatsyayan, Ecology and Indian Myth, India International Centre Quarterly 19, nos. 1–2 (1992), 173.

- Albertina Nugteren, Belief, Bounty, and Beauty: Rituals Around Sacred Trees in India (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Pub, 2005), 425.

- Hymns of the Atharva Veda, tr. by Ralph T.H. Griffith (1895), book 12, hymn 1. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Hymns of the Atharva Veda, book 12, hymn 1.