Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

The poet W.S. Merwin spent the last four decades of his life on Maui, restoring a plot of abandoned land that would become one of the most diverse and expansive palm tree gardens in the world. His poems are living witness to the care he offered to this land.

I want to tell what the forests

were like

I will have to speak

in a forgotten language

—W.S. Merwin, “Witness”1

In 1976, when William Stanley Merwin first visited a three-acre property for sale on the north shore of Maui, he did not yet know its recent history. In the early nineteenth century, it had been extensively logged to provide lumber for whaling ships. After much of the forest was gone, cattle were put out to graze. The water of the stream that once flowed down among the trees had been diverted to the agricultural fields in the center of the island. Most recently, a pineapple plantation had been started and then failed some years later, after the farmers plowed the land vertically—up and down the slope instead of across it—causing what little remained of the topsoil to wash away. For decades, the land had largely been left alone—abandoned and assumed to be beyond use or value.

This small parcel had been pronounced agricultural wasteland, and as William walked through the property, he could see that things were in poor condition: a dry streambed; soil that supported only sparse grass.

He climbed up to the high ridge and encountered a view that looked down on just one building and then out across the great expanse of blue ocean. He walked along the rocks of the silent streambed and then down into the small valley, where he stood in the shade of a stand of mango trees that had been left to grow to their full height. Here he heard the melodious laughingthrush, singing from the trees, a bird that “never repeats itself but sings variations from an inexhaustible source,” he wrote.

“I stood there hearing the thrush and wanting to stay there.”2

On the day he signed the escrow papers, he set about planting trees.

William’s poem “Rain at Night” begins with the lines:

This is what I have heard

at last the wind in December

lashing the old trees with rain

unseen rain racing along the tiles

under the moon

wind rising and falling

wind with many clouds

trees in the night wind3

Maui—the second youngest of the major islands in the Hawai‘ian archipelago—began its rise from a volcanic hot spot in the Pacific Ocean about 1.6 million years ago. The island consists of two shield volcanoes—Kahālāwai in the west at nearly six thousand feet and Haleakalā in the east at ten thousand feet—joined in the middle by a central isthmus.

When the volcanoes cooled and quieted over the ensuing millennia, the early ancestors of what would come to be the endemic flora of the islands were dispersed by migrating birds, wind, and water from across the Pacific. Through hundreds of thousands of years of adaptation and evolution in great isolation, and from an estimated 250 to 300 species of originally deposited seeds and fruits that took root on the islands, there came to be approximately 1,030 unique species of flowering plants and 162 species of ferns across the islands.

Polynesians were the first humans to set foot on the islands, sometime between 400 and 1000 CE. They, too, had carried seeds and fruits across the ocean: taro, breadfruit, coconut, sugarcane, sweet potato. Eventually the four larger islands—Maui, Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, and Hawai‘i—were divided into sections called moku and then organized into ahupua‘a, smaller wedges that ran along the natural boundaries of a watershed, starting from a narrow point at the ridges of the mountain’s summit and widening along a descending valley, out past the shoreline to the reefs. As small streams carried rainwater swiftly down steep forested slopes and into larger streams that ran down the center of valleys, each ahupua‘a held within its bounds the resources that a community needed to survive. One Kanaka Maoli, or Native Hawai‘ian, family might have grown sweet potatoes on the upland fields. Farther down, another would have planted taro, harnessing stream water to fill the lo‘i, or terraced patches, before returning the water—now suffused with nutrients from the taro—to its natural course. Along the coast were the fishponds and fishing villages.

European contact commenced in the last quarter of the eighteenth century with the arrival of Captain Cook, who was soon followed by wave after wave of settlers from Europe and the Americas, seeking to capitalize on the islands’ riches or to convert the Kanaka Maoli to Christianity. The whaling industry and grazing cattle were responsible for much of the early destruction of the rainforests, but it was sugarcane that would prove to be far more devastating to the native ecosystem and the islands’ original inhabitants.

“Rain at Night” continues:

after an age of leaves and feathers

someone dead

thought of this mountain as money

and cut the trees

that were here in the wind

in the rain at night

In order to grow one of the world’s thirstiest crops, growers of sugarcane needed an abundance of water. One acre of sugar can require a daily intake of as much as ten thousand gallons. Nearly nine gallons are behind every teaspoon of sugar. In 1876 construction of Maui’s Hamakua Ditch began. Over nearly half a century, the Hamakua Ditch Company built a network of ditches and tunnels to divert the rainwater coming down the mountains to the plantations in the central valley. As the streams dried up, the taro patches failed and many Kanaka Maoli—already enduring often fatal epidemics of introduced disease and the widespread loss of their language and way of life—were forced to abandon their livelihoods and homes.

American sugar merchants orchestrated the overthrow of the Hawai‘ian monarchy in 1893. As the demand for sugar soared throughout the world, plantations continued to surge across the islands. More forest was cut. By 1917 nearly 130,000 acres of Maui had come under the ownership of sugar plantations and factories.

it is hard to say it

but they cut the sacred ‘ohias then

the sacred koas then

the sandalwood and the halas

holding aloft their green fires

and somebody dead turned cattle loose

among the stumps until killing time

East Maui Irrigation, the successor to the Hamakua Ditch Company, manages fifty miles of tunnels and twenty-four miles of open ditches that pull water from watersheds spanning an area of fifty thousand acres on the eastern side of Maui.

The wasted land that William bought in 1977 is part of an ahupua‘a called Pe‘ahi—the valley and watershed of the Pe‘ahi Stream. When he arrived, the stream had already been dry for over a century, and the land around it stripped of its trees.

“I had long dreamed,” he wrote, “of having a chance, one day, to try to restore a bit of the earth’s surface that had been abused by human ‘improvement.’ I loved the wind-swept ridge, empty of the sounds of machines, just as it was, with its tawny, dry grass waving in the wind of late summer.”4

In the ensuing decades, even when the number of trees he planted here reached into the thousands, he would always refer to the land, not as a forest, but as a garden.

“Rain at Night” concludes:

but the trees have risen one more time

and the night wind makes them sound

like the sea that is yet unknown

the black clouds race over the moon

the rain is falling on the last place5

William was born in New York City in 1927 and grew up in Union City, New Jersey, and Scranton, Pennsylvania. He recalls, as a child, remarking on the grass that grew through cracks in the sidewalk, and his subsequent wonder when his mother told him that the whole earth was there, just below.

His father, a Presbyterian minister, was an unforgiving and repressive man. But it was through his father’s church that William found poetry at an early age, in the form of hymns from the King James Bible. As a boy, he took to writing and illustrating his own hymns, and though his father wouldn’t use them in church, William had become enamored with the power of words.

While in college at Princeton, William visited Ezra Pound, who told him that in order to be a poet, he must learn languages, for “translating will teach you your own language.” He took this advice to heart and did his postgraduate studies in Romance languages. He traveled and worked throughout Europe upon graduating. His first poetry collection, A Mask for Janus, published in 1952, was heavily influenced by his translations of medieval Spanish poetry. William would go on to translate in Latin, French, and nearly thirty other languages. His early poetry is formal and traditional—filled with Odysseus and Leviathan, classical imagery, and the language of myth—as we hear in “Dictum: For a Masque of Deluge”:

There will be the cough before the silence, then

Expectation; and the hush of portent

Must be welcomed by a diffident music

Lisping and dividing its renewals;6

William had discovered his love of gardening, particularly during the years he spent living in a rural village in the South of France. One year, he stopped to watch the farmers, who had gathered to manually separate the season’s harvest of grain from the chaff and stems. The next year, the arrival of the threshing machine brought with it the abrupt end of that ritual of community and cooperation.

While in France, as the war in Vietnam was claiming ever more lives, William wrote his 1967 collection, The Lice, an expression of his grief and pessimism in the face of the immensity of human destruction. The war and his growing understanding of the mark that humans were leaving on the earth had begun to shape the words that he put to paper, and his poetry quickly escaped the bounds of formalism. In “For a Coming Extinction,” he writes:

Gray whale

Now that we are sending you to The End

That great god

Tell him

That we who follow you invented forgiveness

And forgive nothing7

These were poems that “pushed their way upon me,” he said in an interview, at a time when he “thought the future was so bleak that there was no point in writing anything at all,”8—a sentiment reflected in “When the War is Over”:

When the war is over

We will be proud of course the air will be

Good for breathing at last

The water will have been improved the salmon

And the silence of heaven will migrate more perfectly

The dead will think the living are worth it we will know

Who we are

And we will all enlist again9

William had come to Maui in 1975 to study under the Zen Buddhist teacher Robert Aitken. He was living in New York City at the time and was growing weary of city life. Though he remained passionately opposed to the war in Vietnam, he was becoming disillusioned with the political outrage of others that easily spilled into hatred and unrestrained anger.

On Maui he found some of the quiet and anonymity that he had been longing for, along with a climate suited to year-round gardening. Seeing the dust blowing through the scraggly grass of his three acres, he planted a line of Casuarina, or ironwood, trees to serve as a windbreak on the ridge and to shade the ground. He had decided that he would attempt to restore a small piece of Hawai‘ian rainforest. He did not know where or how to begin, so he simply began by putting plants into the soil.

[W]herever I had lived I had tended gardens with no particular skill, and had loved them, and been fed by them, but most of my questions to do with them had been practical ones, for most of them were in places that had been thought of as gardens by other people, for a long time. It was here on a tropical island, on ground impoverished by human use and ravaged by a destructive history, that I found a garden that raised questions of a different kind—including what a garden really was, after all, and what I thought I was doing in it.10

In 1982 William and a woman he had first met in 1970, Paula Dunaway, were at a gathering of mutual friends during one of his stays in New York City. The story goes that he walked her home—seventy blocks; they were married a year later. Within days of moving into the house that William had built with the help of friends over the previous several years—an off-the-grid Hawai‘ian-style home with multiple lanais, or porches—Paula went to work in the garden.

Together they planted several hundred native koa trees. Nearly all of them died, meeting the same fate as the vast majority of native species that William had attempted to put into the ground thus far. A friend from the local arboretum told him he would never be successful in restoring native rainforest: Too much had already been lost and too much introduced that didn’t belong. The soils had changed. Nothing was the same as it had been nearly two centuries ago before the land was deforested.

Hawai‘i is referred to as the “endangered species capital of the world,” and nearly half of the United States’ endangered plant species are on the Hawai‘ian Islands. More than two hundred native plants are thought to have fewer than fifty individuals living in the wild; over one hundred species have already gone extinct. It’s estimated that a new species is introduced to the islands every eighteen days. Having evolved in near-complete isolation, Hawai‘i’s native ecosystems are susceptible to being overrun by aggressive, non-native species that thrive in the tropical climate.

“I said, ‘Well, I can’t restore native forest,’” William recalled in an interview. “I can’t restore native things very well at all. But palms are endangered all over the world.”11

There are an estimated 2,600 species of palm trees in the world, and the palm family, Arecaceae, dates back at least eighty million years in the fossil record. Two hundred twenty palm species are critically endangered, with habitat loss due to the encroachment of human development being one major cause.

And so William began to learn about palm trees. He researched palms from Hawai‘i, Madagascar, Cuba, Australia, Brazil. He began to raise them from seeds and plant them in places on the property that seemed best suited to their preferred climate.

Over the years, he and Paula came into possession of two adjacent properties, expanding their original three acres to nineteen. They planted trees and worked in the garden nearly every day.

It was becoming well known that William was planting palms, and he began to receive the seeds and fruits of different species from friends and visitors, or as gifts when he traveled. He would grow many of the palms in his small garden shed, half of which he built as a Zen dojo. When a palm was big enough, he dug a hole, filled it with a mixture of compost and fertilizer, and placed it in the ground, hand-watering it until it was strong enough to survive on its own.

Both poetry and planting were increasingly truer expressions of the same thing: reaching for the unknown and being in relationship to the world.

William’s days took on a rhythm of meditating, breakfasting on the lanai that extends off the kitchen, writing for the morning, having lunch, and spending the rest of the day in the garden. He did not find questions about the distinction between his time gardening and his time writing to be relevant. He grew dismissive of the labels that people were inclined to attach to him. (“Take them away, names like ‘Buddhism.’ I’m impatient with them,” he said in an interview.)12

Both poetry and planting were increasingly truer expressions of the same thing: reaching for the unknown and being in relationship to the world—from this particular place, its people, and its history. He began learning the native Hawai‘ian language from Dr. Pualani Kanaka‘ole Kanahele, a Kanaka Maoli woman and a widely revered scholar and kumu hula, or hula master.

William’s epic poem, The Folding Cliffs, spanning more than three hundred pages, follows the true story of Pi‘ilani, a Hawai‘ian woman of the late nineteenth century who had fled into the wilds of Kaua‘i with her husband and son as the United States government was seizing victims of leprosy for quarantine. William wrote it as an overlaying of the narrative tradition of Hawai‘ian chant and the Western tradition of epic poetry. Dr. Kanahele, who became a close friend of William and Paula, has been an advocate of the book and recently read excerpts from it to the protectors of Mauna Kea. The story unfolds as an interlacing of the truths of history and creation, of the birth of the islands, and of the love within a family.

The mountain rises by itself out of the turning night

out of the floor of the sea and is the whole of an island

alone in the one horizon alone in the entire day

as a word is alone in the moment it is spoken

meaning what it means only then and meaning it only

once with the same syllables that have arisen

and have formed and been uttered before again and again

somewhere in the past to mean something of the same nature

but different something continuing and transmitted

but with refractions something recognized in its changes

something remembered from what is no longer there

and behind it something forgotten as the beginning

is forgotten and as the dream vanishes the present

mountain is moving at its own pace at the end

of its radius it is sailing in its own time

with the earth turning away under it as the day

turns under a word and it came late as a word comes late13

As the land became healthier, year after year, it began at last to receive many of the native species that William and Paula had continued to attempt to plant.

Over forty years, William planted more than 2,740 surviving palm trees (and thousands more that did not survive), consisting of more than 400 species and 125 genera and nearly 900 horticultural varieties. The garden has come to be known as one of the world’s most extensive palm collections. Some of the palms that grow here are no longer known to exist in the wild and grow only in private collections, where they are often trimmed and manicured in relative isolation. Palm experts who have come to visit William’s garden over the decades have remarked that they’ve never seen fuller expressions of particular species, except in the wild.

The palms all grow side by side, an assemblage of native and foreign species that have come to share the same soil.

In gardening, as my wife and I go about it here, what are called concerns—for ecology and the environment, for example—merge inevitably with work done every day, within sight of the house, with our own hands, and the concerns remain intimate and familiar rather than far away. They do not have to be thought about, they are at home in the mind. I have never lived anywhere that was more true.14

William wrote his final book of poetry, Garden Time, as he was approaching the age of ninety, and with failing eyesight. He dictated the words to Paula, and the voice that rises from the page is one that has fallen deeply in love with the world, with his wife, and with his garden. As we see in poems like “The Present,” the book manifests a long life of learning to listen for the unknown and singing it back to the world:

As they were leaving the garden

one of the angels bent down to them and whispered

I am to give you this

as you are leaving the garden

I do not know what it is

or what it is for

what you will do with it

you will not be able to keep it

but you will not be able

to keep anything

yet they both reached at once

for the present

and when their hands met

they laughed15

The walls of the library on the bottom story of the house are lined from floor to ceiling with books. They are worn, their spines cracked, their pages folded. Atop one inconspicuous shelf sits a dusty jumble of awards—the National Book Award plaque and the glass prism of the Pulitzer Prize (which William was awarded twice: for The Carrier of Ladders in 1971 and The Shadow of Sirius in 2009), among others. In all, he published more than fifty books of poetry and translation and eight books of prose.

The Garden Time poems are free of punctuation, as all of his poems had become over the years, and the words ring clear like a bell—rejoicing in life, singing of loss, knowing both that the world will continue on and on and that time passes too quickly. We hear this in the opening lines of “The Morning”:

Would I love it this way if it could last

would I love it this way if it

were the whole sky the one heaven

or if I could believe that it belonged to me

a possession that was mine alone

or if I imagined that it noticed me

recognized me and may have come to see me

out of all the mornings that I never knew

and all those that I have forgotten16

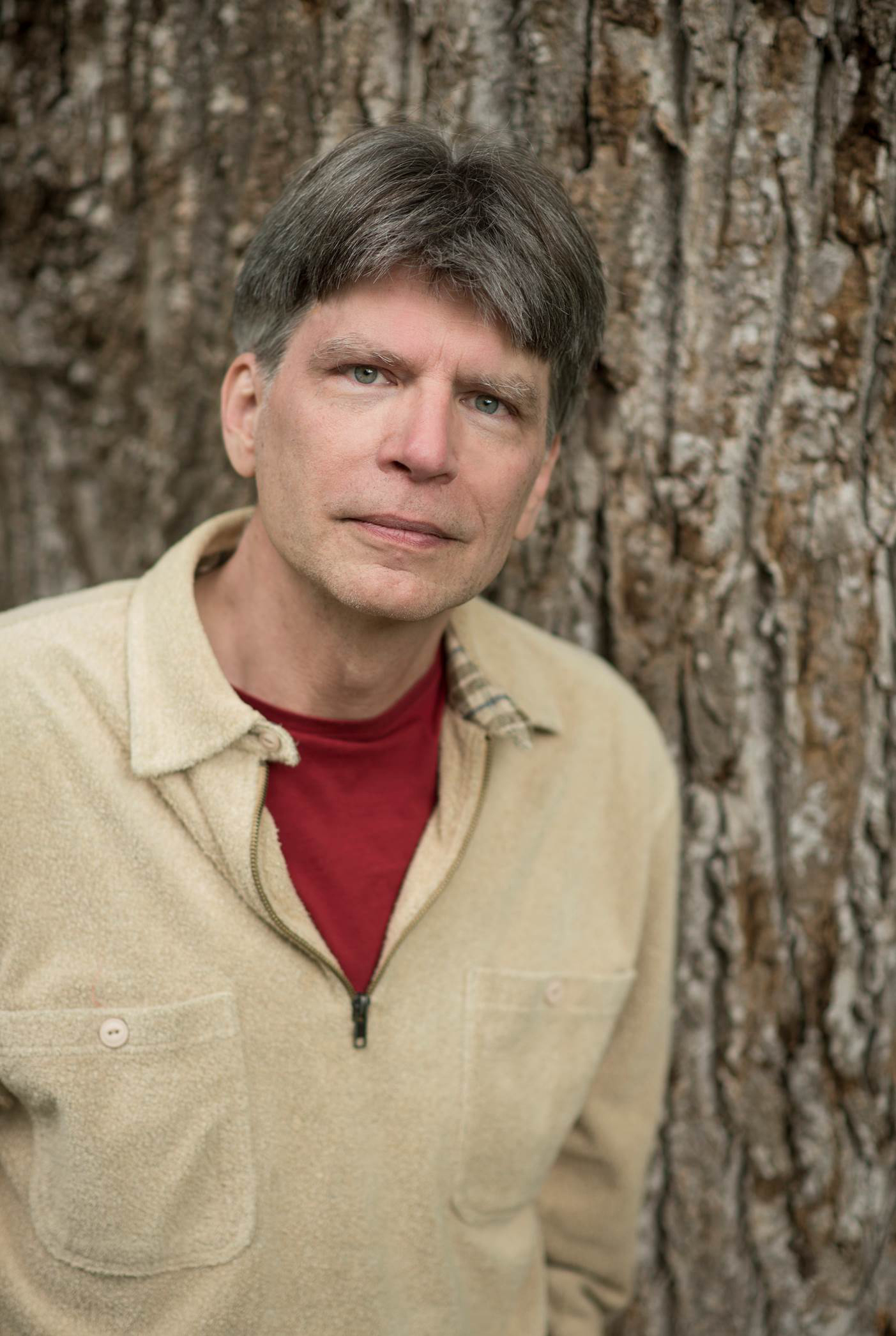

Paula Dunaway in the garden, 1987.

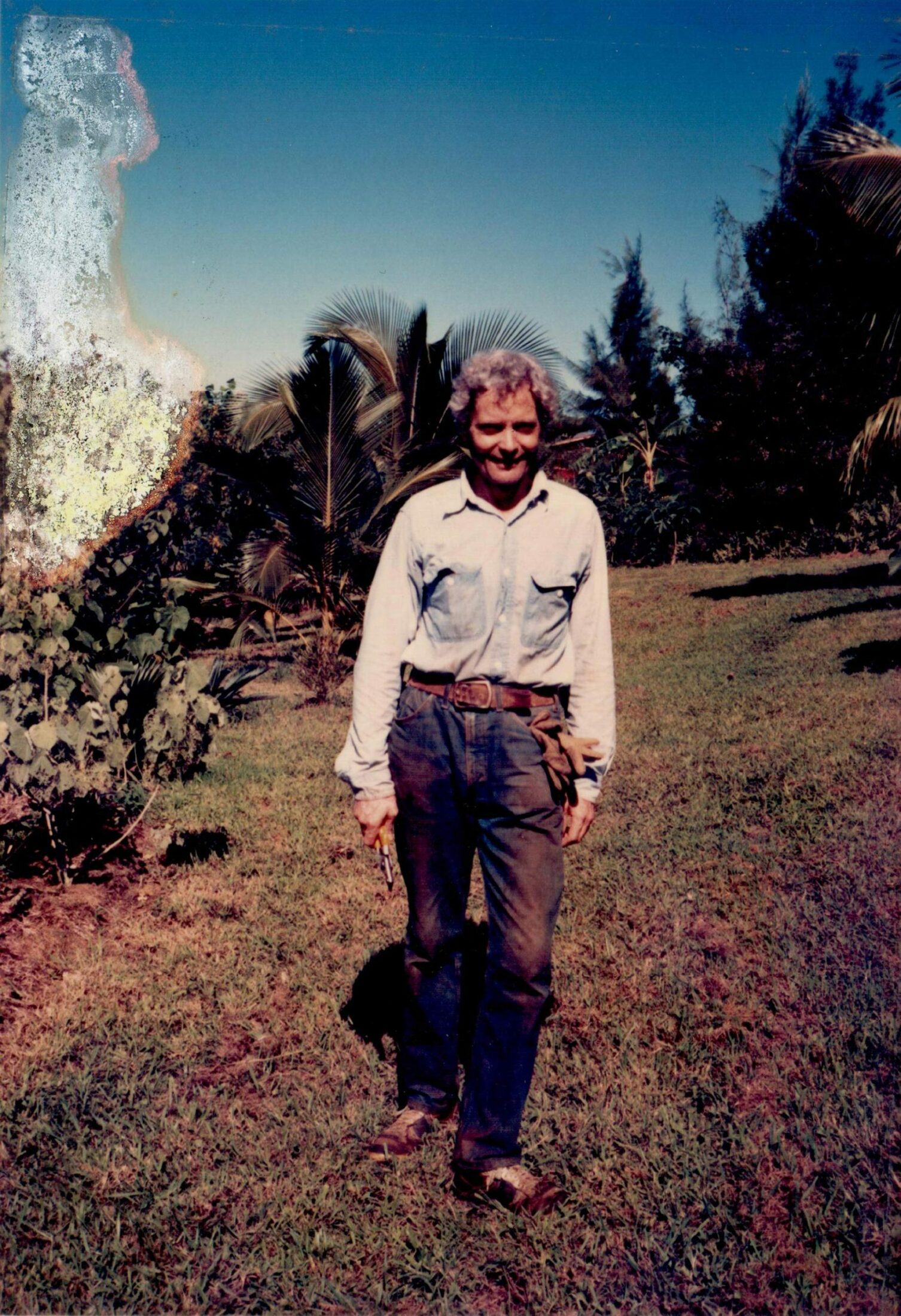

W.S. Merwin in the garden, 1987.

Photos courtesy of The Merwin Conservancy.

The golden vixen affixed to the bright-green door on the front lanai opens into a house that is beautiful and silent. Everything is in its place: a black-and-white photograph of William and Paula on the coffee table; the armchair draped with a blanket; the chandelier; the many, many shelves of books; the wide-brimmed hat on a peg with a dog leash hanging behind.

One book is off the shelf, resting at the corner of the dining table as if someone has just set it down: Red Pine’s translation of Tao Te Ching. The book opens easily to a page that has been read and read. There are notes scribbled in the margins and scraps of paper tucked into the seam. It is Tao Te Ching’s sixth passage, “Valley Spirit”:

The valley spirit that doesn’t die

we call the dark womb

the dark womb’s mouth

we call the source of Heaven and Earth

as elusive as gossamer silk

and yet it can’t be exhausted17

Just a few paces out the door and down one of the narrow paths, there is a polished stone, just beyond the graves that bear the names of William’s dogs, beloved companions to him throughout the years. On the polished stone, the Chinese symbol for the Tao’s sixth passage is engraved at the top. Below it are the names of William and Paula and the words:

Here we were happy.

Paula passed away on March 8, 2017. That same year, William wrote the poem “Wish”:

Please one more

kiss in the kitchen

before we turn the lights off18

He followed Paula on March 15, 2019.

Beyond the stone, their garden is growing. Deep into the trees, over the bridge that crosses the dry stream, past palms and palms, the path leads up to the sheltered ridge with the wide ocean beyond.

In 2010, William and Paula created the Merwin Conservancy. The nineteen-acre garden is permanently preserved under a conservation easement held by the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust. The conservancy formally came into ownership of the land—though the staff prefers the word “stewardship”—in December 2019.

On an afternoon in late November, I am walking through the garden with Walter, a slight man in his early sixties. He has been working in the garden William created for eighteen years, ever since a mutual friend of theirs suggested that the Merwins could use some extra help.

“It’s quiet here now,” he tells me. And then he tells me that he will go on tending this garden, that he has never loved a place as he loves it here.

The life of the land is long, and it continues on.

Somewhere in the canopy, the thrush is singing. His song is lyrical and complex, a whistling trill that finds its way through the broad fronds of palm trees. The sound is as sure and fitting as the overhead thrum of the brief afternoon rain, whose drops are caught and diverted in the trees and seem never to reach the ground. The thrush and the rain are elusive, their physical forms hidden in the trees, presences felt through melody.

The effect of looking out into the trees is one of a confounding array of infinitely layered green. The scene is like a fractal, the same intricate patterns recurring at ever smaller scales. Fanning-leaf green. Light-filtered green. Draping, curving green. On down to the veins of saplings and the moisture reflected on moss.

Up the Pe‘ahi streambed, in the direction of the mountain summit where the valleys begin to unfold in their wide fan, the demands of the Kanaka Maoli and their allies to return the water to its natural watersheds are beginning to be heard at last. Perhaps one day water will flow again into the many ahupua‘a and the taro lo‘i and into the Pe‘ahi Stream, through the garden that has grown around it.

Whether we direct our gaze to that which is small or cast it out wide, it will eventually touch a point that lies beyond what the eye can see.

In “Place,” William reminds us of our role as gardeners—of the presence and witnessing that lies at the heart of our relationship to the world:

On the last day of the world

I would want to plant a tree

what for

not for the fruit

the tree that bears the fruit

is not the one that was planted

I want the tree that stands

in the earth for the first time

with the sun already

going down

and the water

touching its roots

in the earth full of the dead

and the clouds passing

one by one

over its leaves19

- W.S. Merwin, “Witness,” currently collected in The Rain in the Trees (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988), 65. Copyright © 1988 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

- W.S. Merwin, “The House and Garden: The Emergence of a Dream,” Kenyon Review (Fall 2010).

- W.S. Merwin, “Rain at Night,” currently collected in The Rain in the Trees (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988), 26. Copyright © 1988 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

- W.S. Merwin, “The House and Garden: The Emergence of a Dream.”

- W.S. Merwin, “Rain at Night,” currently collected in The Rain in the Trees (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988), 26. Copyright © 1988 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

- W.S. Merwin, “Dictum: For a Masque of Deluge,” excerpted from The Essential W.S. Merwin, ed. Michael Wiegers (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2017), 5. Used with permission from the Merwin estate, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/the-essential-w-s-merwin/.

- W.S. Merwin, “For a Coming Extinction,” from The Lice (1967) collected in The Second Four Book of Poems. Copyright © 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1993 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/the-second-four-books-of-poems-by-w-s-merwin/.

- W.S. Merwin, “An Interview with W.S. Merwin,” interview by David L. Elliott, Contemporary Literature 29.1 (Spring 1988), 1–25.

- W.S. Merwin, “When the War is Over,” from The Lice (1967) collected in The Second Four Book of Poems. Copyright © 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1993 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/the-second-four-books-of-poems-by-w-s-merwin/.

- W.S. Merwin, “A Shape of Water,” in The Writer in the Garden, ed. Jane Garmey (Port Townsend, WA: Algonquin Books, 1999), 14.

- W.S. Merwin, “W.S. Merwin: At Home in the Garden of the Unknown,” interview by Noe Tanigawa, Hawai‘i Public Radio, April 30, 2019.

- Joel Whitney, “The Garden and the Sword,” Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Winter 2010.

- W.S. Merwin, excerpted from The Folding Cliffs: A Narrative of 19th-Century Hawaii (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1998), 47. Copyright © 1998 by W. S. Merwin. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

- W.S. Merwin, “Living on an Island,” Sierra Magazine.

- W.S. Merwin, “The Present,” from The Lice (1967) collected in The Second Four Book of Poems. Copyright © 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1993 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/the-second-four-books-of-poems-by-w-s-merwin/.

- W.S. Merwin, “The Morning,” currently collected in Garden Time (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2016), 3. Copyright © 2016 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/garden-time-by-w-s-merwin/.

- Lao Tzu, Lao-Tzu’s Taoteching, trans. Red Pine (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2009), 12. Reprinted with permission from Copper Canyon Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher, https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/lao-tzus-taoteching-tr-bill-porter-red-pine/.

- W.S. Merwin, “Wish,” from The Essential W.S. Merwin, ed. Michael Wiegers (Port Townsend: Copper Canyon Press, 2017), 323. Used with permission from Copper Canyon Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/the-essential-w-s-merwin/.

- W.S. Merwin, “Place,” currently collected in The Rain in the Trees (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1988), 207. Copyright © 1988 by W.S. Merwin, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.