Practice 07

Playful Listening

by David G. Haskell

For billions of years, our planet has been alive with sound. When we listen playfully, we can still encounter sonic vibrations older than terrestrial life, layered with the harmonies and cacophonies of the modern world. This practice by David Haskell invites you to immerse yourself in the web of connections created by sound. To hear what the ancient Earth might have sounded like, listen to David’s companion sonic journey “When the Earth Started to Sing.”

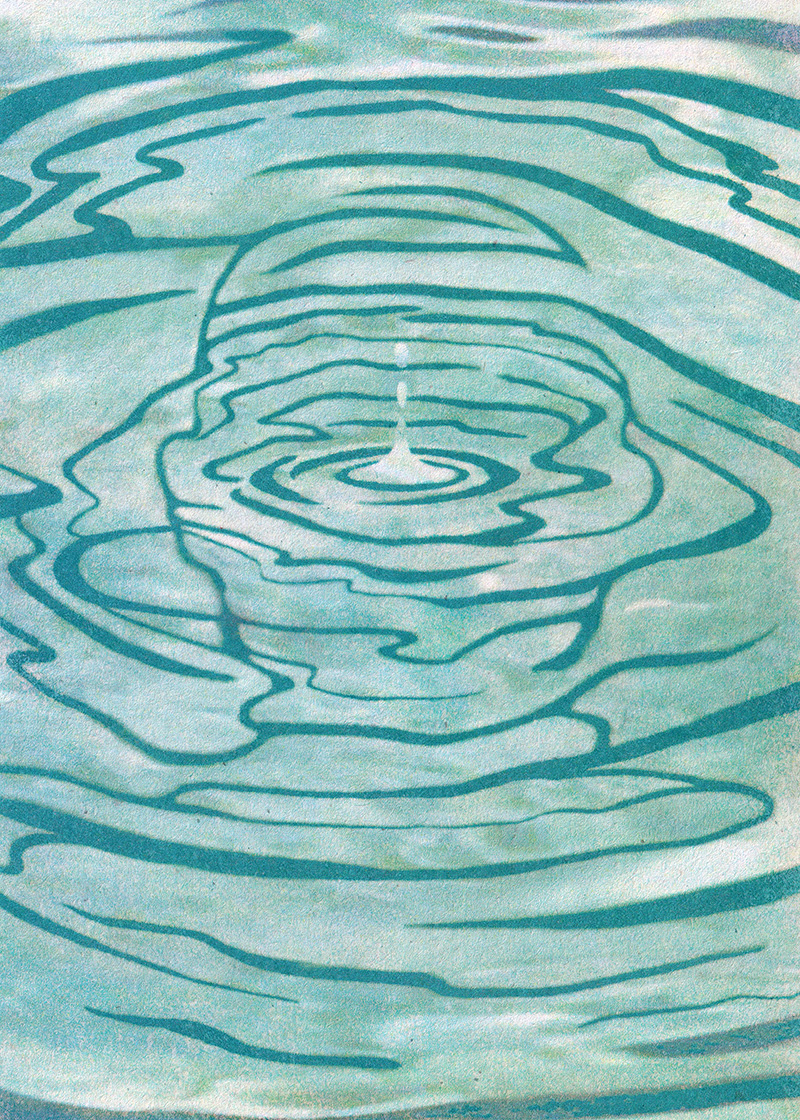

Sound is ephemeral, gone as soon as it arrives. Sound is tiny, too. A typical sound wave makes air molecules vibrate by only about a micrometer, the size of the smallest smoke particle. Yet, despite its fugitive and insubstantial nature, sound is a great connector and revealer. Sound passes through obstacles. It links vibrating beings even in the dark or in dense foliage. Listening therefore opens us to what is hidden or unappreciated. Sound also carries within it the imprints of deep time. Listening roots us in the stories of the ancient Earth.

In the midst of landscapes that are shifting on often unimaginably large scales, what might it mean to witness the tiny and ephemeral? How might we cultivate our listening? The practices that follow are intended as invitations to play. Their aims are the cultivation of spontaneity, curiosity, and grateful appreciation.

Spontaneity: Openness to the sensory qualities of the moment.

Curiosity: Every sound has a story. Follow it.

Grateful appreciation: Accepting the wondrous and bittersweet bequest of sensory consciousness, in all its beauty and brokenness.

Illustrations by Daniel Liévano