Kiliii Yüyan is a photographer and storyteller who has spent years immersed in the polar regions, documenting Indigenous lifeways, marine ecosystems, and remote landscapes. Of Chinese and Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous) descent, he works through a cross-cultural lens, exploring how humanity—inseparable from nature—lives in relationship with land and sea. Kiliii is an award-winning contributor to National Geographic and other major publications, including TIME, Vogue, and Wired. His work has been recognized by Pictures of the Year, Leica Oscar-Barnack, PDN, and ASMP, and is held in museum collections across the US. In 2023, Kiliii received the National Geographic Eliza Scidmore Award for Outstanding Storytelling. He also builds traditional kayaks, maintaining a living link to his northern Indigenous heritage.

Photographer Kiliii Yüyan visits Utqiagvik and Kotzebue in Alaska, where he witnesses how climate change is remaking the Arctic tundra and shaping the future of wilderness.

Well suited for frigid conditions, musk ox will stand steadfast against thirty-knot winds and temperatures well below freezing.

Musk ox in this region were driven to local extinction by the early 1900s. Herds like this were reintroduced from Greenland.

A red fox near an expedition camp in the Alaskan Arctic. Red foxes have moved north where they are displacing—and likely driving to extinction—their smaller cousins, the Arctic fox.

The northern lights flash and fold outside the town of Kotzebue, Alaska. With more and more development, the light pollution from this tiny town has begun to overshadow the aurora’s light.

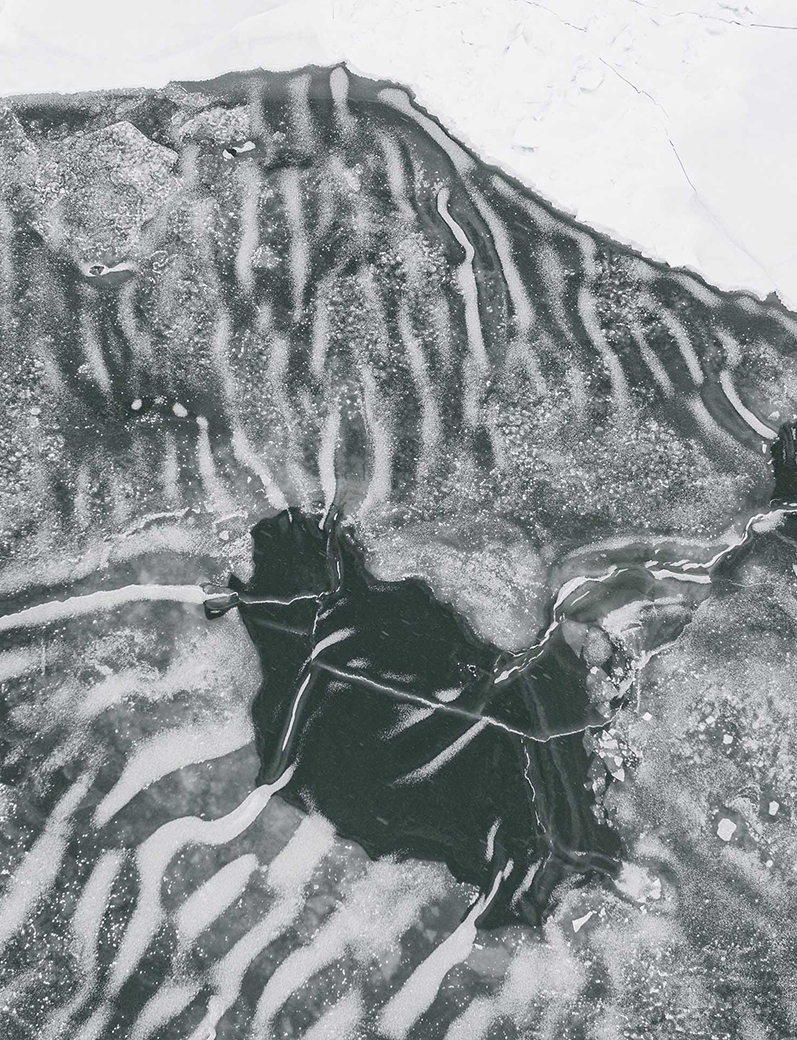

Sea ice has become terribly thin in the past decades. In the Alaskan Arctic, the condition and quantity of sea ice affects all life, from the migration of beluga whales to the ability of ancient human communities to secure food.

Andrew George, an Inuk from Kotzebue, Alaska, jigs for sheefish on the Bering Sea. Sheefish have become a critical source of subsistence since the caribou changed their migration patterns.

Iñupiaq subsistence hunters scout an enormous crack at the edge of the thinning sea ice.

Wildly fluctuating temperatures have caused the Arctic Ocean to be covered in a thin layer of newly formed ice, coated by a layer of hoarfrost.

(left) A deep wound in the sea ice shows signs of having healed and then flexed apart again in late winter.

(right) Newly formed sea ice, as seen from above. At this time in the spring, temperature swings have created unusual sea ice formations.

A rare formation of multiyear ice. Most sea ice no longer lasts through summer, shortening the season that polar bears can hunt.

Light from a blazing sun reflects off the sea ice, forming a halo in the icy mist.

As permafrost disappears, the river eats away at this eroding riverbank, altering the flow of water and the surrounding landscape.

The surface of Esieh Lake appears to boil as permafrost thawing beneath the lake releases methane.

A thermokarst pond on the tundra shows the telltale signs of thawing permafrost: “drunken” trees, formerly rooted in stable soil, list and fall into the water.

Drunken trees atop an eroding riverbank. In this infrared image, organic material shows as bright yellow—including the exposed ancient material that was once encased in permafrost.

This wide and shallow bend in the Noatak River is a typical pattern in regions with thawing permafrost.

A spire of rock rises out of the tundra near Hugo Mountain, evidence that the movement of giant glaciers from the last ice age was not uniform. Sites such as these became refuges for some species as other places became inhospitable.

Drunken spruce trees tilt at various angles above a hidden stream that moved underground as the permafrost thawed.

A brand new beaver lodge. The population of beavers has exploded in the past decade, indicating that beavers will greatly alter the landscape above the Arctic Circle.

“Thermokarst” is a term that refers to areas of pooling water and marsh formed by melting permafrost. These formations create difficult terrain for caribou migration.

A lake created by beavers contributes to the melting of permafrost in this thermokarst landscape.

Though they negatively affect caribou, thermokarst lakes can provide habitat for nesting migratory birds.

The Arctic occupies a paradoxical space in the Western mind: it is simultaneously conjured as a timeless, unpopulated, pristine wilderness; and as a place where time is running out—an hourglass in which the landscape embodies the rapid acceleration of the climate catastrophe. Though I come from a family of two distinctly non-Western cultures, I was raised in America and grew up holding this dual notion of wilderness as both idealized and disappearing.

As a photographer, I understand the urge to freeze a perfect moment in time—an echo perhaps of the conservationist’s desire to return the wild to an idealized state, sans people. But as I spend time documenting the dynamic Arctic, I am repeatedly reminded that wilderness is ever-shifting and that humans have always played a part in that change. Yet where we once were stewards and reverent participants, we are now impacting ecosystems beyond our horizons.

These images—taken in Utqiagvik, Alaska, in winter and Kotzebue, Alaska, across many seasons—offer a glimpse into how climate change is remaking the tundra and shaping the future of wilderness. The sea ice is becoming thin and unstable, creating landscapes that Iñupiaq elders no longer understand; the permafrost is thawing and altering the shapes of rivers and the paths of caribou. Landforms, animals, and humans alike are adapting to unprecedented change.

In this time when transition is coming faster than ever, we must relearn how to see the wild as it really is: Our home. Ever-changing.