Sjón is an Icelandic poet and author whose novels have been published in over thirty-five languages. He is the author of The Blue Fox, winner of the Nordic Council’s Literary Prize; From the Mouth of the Whale, shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize; Moonstone—The Boy Who Never Was, winner of the Icelandic Literary Prize; and CoDex 1962, published by MCD Books in the US. In 2001 he was nominated for an Oscar for his lyrics in the film Dancer in the Dark.

Philip Roughton is an award-winning translator of Icelandic literature. He earned a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and has taught medieval, modern, and world literature. His translations include works by Halldór Laxness, Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, and other prominent Icelandic writers.

Ink

—an essay by Valur Sveinsson, Chargé d’Affaires

When I was a child, I was sometimes led to think that I had the gift of second sight. It was never stated directly, but I remember remarks such as: “He’s seeing something, the dear.” Or: “I wonder who he’s listening to now, the little one.” I would then be regarded with a mix of interest and worry.

That was in the days of the old Experimental Society, when the city’s elite still actively searched for the world beyond and attempts were made to approach the matter of the afterlife in a sensible manner—before the society’s board was overrun by poets, pastors, and speculators’ wives, and its name changed to the Psychical Research Association. My parents were pioneers in that remarkable experimental activity. My father was trained in law and my mother home-taught in Latin and Greek: educated people and spiritually minded. Still, I have little memory of anything that might be called a transcendental experience—at most, I remember having once stood alone in the doorway of the dark dining room, looked into it and felt a presence in the shadow of the big cupboard, where nothing should have been. Many people have similar memories from their childhood. But from within the drawing room behind me, I heard my mother’s voice say: “Well now, it appears to me as if someone has made contact with him.” Her statement was followed by silence, and I knew that my parents were leaning forward in unison on their armchairs to get a better look at me. This talk about my “gift” stopped around the time that I started elementary school. But until I moved away from home at the age of twenty, my parents sometimes spoke of me as being “a special kid.” Then it was forgotten, having burned up on the fire of the Great War, like most other things from those wonderful years. Many people of my age don’t remember anything that took place before nineteen hundred eighteen.

I bring this up now, to begin with, because I believe that those “lost moments” of mine saved me when I first witnessed the phenomena told of in the essay that follows. For it is almost certain that anyone who encountered such phantasms unprepared would have been shaken to the core. Despite my having little but a veiled memory of being considered clairvoyant as a child, the notion was still somehow deep-seated enough that I already expected such a thing might happen to me, that it was even unavoidable that I would one day encounter something resembling the supernatural beings my father and mother considered me to be in contact with when I was a child. Despite, however, the experience that I describe hereafter being a baptism of fire that I wouldn’t wish on anyone, I also would not want it never to have happened. As difficult as the experience has been for me, I cherish it. For it confirms that my parents’ belief in my special gifts was not misplaced, and now I feel as if I better resemble the good son whom they longed to have but did not get to know during their lifetimes.

You see, it was after my first encounter with those apparitions, which I have chosen to call The Inkborn—an encounter that should have driven me mad but didn’t—that I began to ponder my own lack of fear in the face of them, and realized whence it came:

When I was young, I was told that I was psychic by people who loved me.

* * *

The first one that I saw was a young man. It was at the start of the second week of December in the year nineteen hundred fifty-two, on the corner of Eccleston Street and Belgrave Road, three streets east of my workplace, the Embassy of Iceland in the United Kingdom. The pavements were always crowded with people during rush hour, many waiting to cross the wide, heavily trafficked streets from four directions, some on their way to Victoria Station or the Underground, others coming from there. The traffic lights controlled the flow of people, as though transferring herring in a mass from one tank into another, and then a third, and a fourth, in equal, alternate portions, until the late-afternoon dusk deepened into the darkness of night. This is how I still see things: with the eyes of someone from a fishing village.

Despite having grown up in a sparsely populated place—where a car had never been seen until the only straight road through the centre of the village was widened specially for one, shortly after my eighth birthday—I’ve always felt comfortable in crowds, amid the din of traffic. Toward the close of the workday, I start looking forward to leaving the building at Eaton Terrace, walking from there out to the main road with its speedy vehicles of all shapes and sizes, breathing in the sweet exhaust fumes and listening to the symphony of the auto engines. For these reasons, I made it my habit while returning home not to hurry, and instead of immediately joining the crowd waiting at the intersection to cross quickly as soon as the light turned green, I hung back, sticking to the pavement in front of the restaurant on the north side. From this excellent spot of mine, I could undisturbedly observe the coordinated movements of people, traffic lights, and vehicles.

And there I was standing, that afternoon in the final month of the year, when the young man came walking out of the crowd of people waiting, backs turned toward me, to cross over to the opposite corner, as if he’d remembered something that he’d forgotten to bring with him from the office and therefore decided not to accompany the crowd over the street but instead to go and get it. I found that the most likely explanation, having myself sometimes needed to take work home with me.

Judging by his clothing, I guessed that he was an employee of the government, perhaps the Ministry of Transport, which wasn’t far from there. He was wearing a long woollen coat and a Scottish scarf, the hem of his well-pressed dark trousers touching the tops of his black leather, ankle-high shoes. On his head he wore a speckled flat cap, its ear flaps hanging down. The cap clashed with the rest of his attire but suggested to me that he was more likely an expert advisor at the ministry than a clerk, perhaps a natural scientist who did studies of the impact of laying highways through the breeding grounds of wetland birds. In his gloved right hand, he held the silver-coloured handle of a briefcase, probably a gift from his girlfriend or young wife; it looked to be a finely made thing of foreign design, either French or Italian.

It may perhaps raise some eyebrows as to how I can precisely describe a person whom I’d basically only caught a glimpse of, on the corner opposite Victoria Station, at seventeen minutes past five that eighth of December, nineteen hundred fifty-two, as he turned on his heel in the throng and walked quickly past me. Let alone considering how unusual the conditions were.

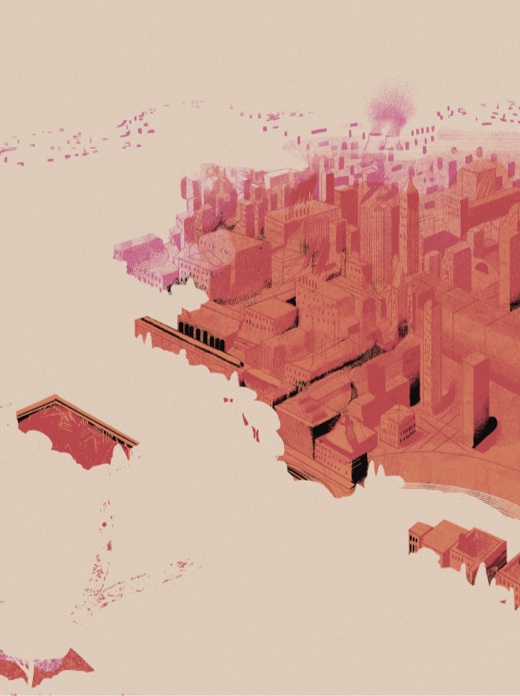

A dense smog had lain over the city for three days. The streetlights, which had barely managed to oppose the winter darkness, had no chance now that the pollution teamed up with it. In the city’s narrow streets, people could see the space of only three steps ahead. Radio London delivered news of horrible accidents and deaths. Thieves took advantage of the situation, raiding homes as much as warehouses, and violence was committed against women and children. Hospital casualty departments filled with citizens, old and young, who had difficulty breathing when the particulates began accumulating in their lungs. Policemen put themselves in mortal danger trying to control the traffic from within the cloud that covered the intersections, and blew their whistles as hard as they could in the hope of both preventing collisions and being run over themselves.

Government experts were in no doubt about the cause of this nearly impenetrable haze. In the extreme cold that clamped itself onto the capital city, the citizens responded by heating their homes more zealously than usual. The coal-fired power stations could barely keep up, and spewed more smoke in three days than during the three preceding months together. A warm-weather lid trapped the bitterly cold air and prevented even its slightest movement, condensing it with each passing moment—the coal-smoke particles that were ordinarily imperceptible to the human eye now overwhelmed it. Later, it was stated that the exhaust from the diesel buses that had recently replaced the electric trams also played a part in it.

By day the smog turned an ochre colour. In true British fashion, the tabloid wags gave it a mocking nickname:

“The Pea Soup.”

Yes, so you see, there was an unusually small number of people out and about on that fourth day of self-imposed suffering, at the moment when the well-dressed young man stepped out of the dense haze on the corner of Eccleston Street and captured my attention. Unlike the rest of us, he didn’t have his scarf wrapped around his nose and mouth to filter out the bad air. However, even though he headed straight toward me, I was unable to see his face. It was as if he were looking away, despite his head clearly facing straight forward. And just like that, he walked past me, so close to me that his left shoulder brushed against mine.

On my way home to my bachelor pad in Chelsea, I recalled a photograph from my childhood home. It was of my grandmother and her two sisters, taken when they were teenagers. The photographer was the first professional one in Iceland. He had studied photography in Copenhagen, but after attempting to slit his own throat in desperation over how poorly he was doing at mastering its techniques, he was sent home to Reykjavík in the fall of eighteen hundred sixty. He didn’t make any progress after coming home, and the photo of the sisters, which he took a few years later, was a witness to that fact. The only thing that was left of the models were my grandmother’s eyes—but because she had moved them while the lens was open, the poor man had decided to draw her a new pair of eyes in brown ink. It was those two eyes that looked out from the pink blur that had once been three girls in their Sunday best.

The situation in London improved two days later, when the smog was finally dispersed by wind. Human intervention had no say in the matter. The dirty-yellow pollutant soup disappeared as if a hand had been waved, leaving nothing behind but soot in the residents’ respiratory systems. Around six thousand people died in the years following from diseases that could be traced to their having breathed in the toxic “pea soup.” Mainly it was people vulnerable from underlying medical conditions: for instance, former tuberculosis patients who had undergone hard struggles to recuperate and numerous men of my generation who had survived the mustard-gas attacks in the trenches in the First World War, but not without permanent damage to their lungs.

I didn’t suffer any side effects from the smog, having never taken part in any wars apart from those fought on the carpets of export companies and ministries. First as a business secretary for the fishing company run by the Ásgarður brothers, close cousins of mine on my father’s side, and later as a business and cultural representative, after the big brother (Úlfur) became a government minister and had his little brother appointed ambassador to Iceland’s main trading partner, the United Kingdom. I followed Ásgeir into the foreign service, rather than take part in politics along with Úlfur. But that’s another story.

The only memento that I had of those murky days in the capital was a dark, palm-sized stain on the left shoulder of my dapple-grey winter coat. I hadn’t given any thought as to how it had gotten there until the owner of the dry-cleaning service mentioned it when I went to pick up the coat. In the poor visibility of that awful smog, one was always brushing up against walls, light poles, or newsstands.

“It was ink,” he said affably as he took the coat off the rack on the wall behind him and laid it between us on the counter to bag it. “Writing ink. But she came out easily, see.” He stroked the material with his fingertip, which he then turned over to show me that nothing was on it. I leaned forward to take a closer look under the strong light of the fluorescent bulb. It was perfectly clean.

Two thoughts flew through my mind:

a) The relationship between fingertips and ink.

The cultural, centuries-old one: the closeness of the fingertips of writers and illustrators to the tips of quills, penholders, and fountain pens, which often leak. The black smudges on the fingers of people working in print shops.

The social, modern one: Scotland Yard’s collection of fingerprint cards.

b) The owner had said that “she” had come out easily from the coat. So “ink” must have been a feminine word in his mother tongue. I’d never been able to determine where his accent originated, other than it being from mainland Europe, but this slip of the tongue might have held a clue.

“You can’t rule out that some of it’s left in the stitches. They’re cotton, rather than wool. You’re lucky they’re dark.”

He finished bagging the coat. I paid the stated price and thanked him for his services, and we said our goodbyes.

Then, on the Monday after the city had cast off its poisonous cloak, I saw the young man again. He was standing on the pavement in the midst of the crowd, which was on its way home at the end of the first day of the work week. I was at my vantage point on the corner. As I happened to be a bit earlier than usual, he was still in the middle of the throng, which gave me an opportunity to take a better look at him from the back. He was taller than most of the people around him and stood very straight, with the same coat as before covering his broad shoulders. On his head he was wearing the same speckled cap with its ear flaps hanging down, revealing wavy, dark-red hair where it ended at the lower back of his neck. So, he was an Irishman or a Scot, possibly Hebridean—a Celt with a Nordic physique, in any case. A moment later he turned around, just as he had done the first time.

I was seized by a longing to walk over to the young man and look up, in order to get a definite look at his face. But just as I was about to take my first step toward him, this longing quickly gave way to the memory of how our shoulders brushed against each other in the smog, and with it came the irrational thought that that was how I got the ink stain on my coat.

Prompted by this thought, I stepped quickly aside as he passed me, and before I knew it, he was already some distance up the street. But just before I lost sight of him at the intersection of Eccleston Street and Chester Square, the winter sun managed to slip in between the buildings and glint off the silver handle of his briefcase. And now the briefcase appeared to me even more exotic than when I noticed it on the eighth of December. Not only did it look to be a product of high fashion from the mainland but also, or more so, as if it belonged to a different civilisation than our own modern one, an unfamiliar civilisation that seemed to bear strong marks of having a common origin with the Western one, but to have then developed under different, unknown premises. How the wife or girlfriend of the young man found such a unique object was a mystery to me, as I imagined her to be ordinary in every respect.

It also caught my attention that her husband or boyfriend headed in a northwesterly direction, rather than eastward, where the Ministry of Transport was situated. So he wasn’t returning to his workplace. And I doubted that he lived in such an upscale neighbourhood as Knightsbridge, whither he was marching with his mysterious briefcase.

* * *

As can be inferred from all of the above, at the end of the year nineteen hundred fifty-two, my senses and ability to draw conclusions were unusually strong.

* * *

Part and parcel of the job of a chargé d’affaires is an unavoidably full social calendar, and even if you prefer solitude by nature, you must push that preference aside and attend banquets, lunches at private clubs, premieres, annual receptions held by the British Parliament, “parties,” dinners and all sorts of other festive gatherings—this particularly applying in the case of a small delegation, such as the Icelandic one, in which every person counts.

Every now and then, the embassies held events involving their countries’ authors, and if I were lucky enough to be seated next to one of them at a restaurant afterward, it could be quite enjoyable hearing more from that person about his or her life and work. Otherwise I found most of this to be boring obligatory work, and it was rare that I met interesting people.

The only events that I attended voluntarily were the extremely interesting lectures held by the Swedenborg Society, to which I was invited as a special guest of the Swedish ambassador. There, the ideas of Emanuel Swedenborg, the great scientist, philosopher, and mystic from Stockholm, were discussed and analysed. Not least, the fundamental principle that he elucidated in his chief works: that the natural world is an imperfect image of the spiritual world. And not only in the larger context but also in the tiniest of details. Everything that exists in earthly life can be found there in a more sublime version; it is from there that created things derive the beauty that the poets sense lies behind their material manifestation.

“I have seen the spirits, and they wear hats,” he writes in one place—and this is a good illustration of the principle.

However, it is not just the sweet sides of existence that have their model in the spiritual world, but all that is ugly and evil as well, as implied in the title of one of Swedenborg’s most famous books, Heaven and Hell.

The uninitiated might think that the society’s activities in connection with an eighteenth-century thinker had mainly to do with old, tired ideas. But this was far from being the case; the society was constantly examining the contemporary world under the light of the lamp that was lit by Master Emanuel and still burns—as witnessed by the lecture “The Latest News of the Veil,” which was delivered at a closed meeting for a select group of society members, on Sunday the twenty-first of December in the year of the Great Smog.

This lecture was delivered by a true successor of Swedenborg, a man who was both a trained physicist and a psychic. (At his request, I will not mention his name here.) The lecture’s subject was an event that weighed heavier on most of the attendees than the recent air pollution catastrophe. It was the hydrogen bomb “Ivy Mike,” which the Americans detonated on the first of November on Elugelab Island in the Enewetak Atoll. The explosion so powerful that the island vanished beneath the surface of the ocean, along with everything on it, living or non-living.

By means of the integration of his knowledge of the latest advances in science and his ability to travel to the border of material reality and the intangible, the lecturer was able to confirm what many of us feared, that the divide between this world and the other had been subject to such trauma from the explosive yield of the superpowers’ thermonuclear weapons tests that the delicate, gossamer membrane that stretches over it—like the dried cauls used for panes in the windows of Icelandic turf houses—was in great danger, having thinned so drastically.

And now he announced, to the trepidation of his audience, that the intense heat of the new, giant bomb had caused a tear in that membrane.

* * *

Shortly after the “secret” meeting at the Swedenborg Society, I had my third and final encounter with the young man at the intersection. As before, he turned on his heel and left the group of people waiting for the green light. Alert to the possibility that he might be “a visitor” from the spirit world, I noticed that his movements were the same as before, down to the smallest detail.

It was as if I were re-watching a scene from a movie, in which nothing changes now that it’s been caught on film. Even the slightest movement was the same as before. And his head was still turned in that peculiar way that allowed no glimpse of his face. I stepped nimbly aside to allow him to pass, but this time I decided to follow him.

It was easy for me to follow him without his noticing it—all chargés d’affaires are given training in what we shall call “information gathering”—and before I knew it, we came to the place where I’d lost sight of him last.

He continued on to Chester Square and went directly to house number twenty-four. There, he knocked on the door and was let in. I lingered for a moment, and then walked past the house. Without slowing down, I peered through the window facing the street. In the yellow light of a crystal chandelier, I saw a group of people, and from their body language I could tell that they were greeting the young man as he entered the room.

Without knowing how I’d gotten there, I suddenly found myself standing in the house’s entryway. A babble of voices carried from the room with the crystal chandelier. I was going to move closer to try to hear what these people were talking about, but then a small bell was rung somewhere within the house and all the voices went quiet. Next, I heard the shuffling sound of footsteps. I hid behind a tall houseplant standing on a low column and watched as the group came out into the hallway. In it were people of various ages, classes, and races. I watched them disappear into a parlour at the end of the hall. Last to go in was the young man, who walked beside an older woman wearing a shoe-length, flaxen skirt. The skirt’s hem dragged along the floor, and it looked to me as if it were soaking up black ink from the thick, wine-coloured carpet. The ink was drawn up into the fibres of the skirt’s material and had reached as high as the woman’s calves by the time they walked through the door of the parlour and the door was closed behind them.

Then I slipped into the hallway. The carpet squished beneath the soles of my shoes, as when fingertips are pressed one by one onto an ink pad for fingerprinting. The next thing that I remember is being behind the parlour’s window curtains. I slipped my finger between the curtains, separating them just enough for me to see what was going on.

In the middle of the room was a lectern. At the lectern stood the older woman, and the young man next to it. The woman’s mannerisms made it clear that she was the hostess in this house. She introduced the young man by name and stated that he had come to tell them a story, whose name or author I can’t recall. Then she stepped aside, and he took the floor.

He opened the briefcase with the silver handle and from it removed a folder. After informing his audience that the story he was about to read would not be written until the year of the great pandemic in two thousand twenty, he began. His audience listened attentively. The room was dead silent, apart from a cough or two from those who were still under the weather from breathing in the harmful contents of the pea-souper, which persisted in their respiratory systems.

I couldn’t begin to describe the story in detail, but it was in fact about “the pea soup” and how he, John Victor Johnson, an employee of the Ministry of Transport in the year nineteen hundred fifty-two, would in the wake of that calamity put together a report or long-term forecast in which he concluded that if nothing was done about pollution issues on Earth, the same sort of situation as had occurred in London would become a global problem and eventually the cause of human extinction. No one would listen to his ideas. He would be seized with ever-deepening despair, be forced out of his job, and lose his young wife—so, there was a beloved involved!—and end up alone and abandoned in a room in a filthy guesthouse in the eastern part of the city. From there, he would write one letter after another to persons in authority, the BBC, newspapers and magazines, former colleagues of his in the ministry, but without success, until finally taking the desperate measure of sabotaging the coal-fired power plant in Battersea. There he would be arrested, just as he was planting a homemade bomb. Subsequently he would be jailed and charged, but finally judged not guilty by reason of insanity, and sentenced to lifelong confinement in the Bedlam hospital. The young man finished his story by saying that he would become one of the last patients in Britain to undergo a lobotomy. Then he fell silent.

He was applauded, though rather sparsely, given the tragic conclusion to his story.

All of this apocalyptic talk had made me drowsy, but now I forced my eyes back open to see how the audience had taken it. I widened the gap between the curtains slightly and looked from one person to another, but everyone in the room was turned from me in such a way that I couldn’t see their faces. The hostess complimented the young Johnson on his reading and said that the story was skilfully written; just one detail bothered her, which was the avant-garde design of the briefcase. Otherwise, the writer had researched his chosen time period well.

A chill ran down my spine. I stifled a scream; these were The Inkborn.

Suddenly, I felt as if I were back in the drawing room of my childhood home, at the conclusion of a séance held by the Experimental Society.

“Valur? Valur, is that you behind the curtain?”

It was my mother’s voice calling to me.

I looked up. On the wall opposite me was an ink-black mirror.

My reflection tilted its head down and to the side, as if avoiding looking into my eyes.

* * *

Written and attested as true and accurate, to the best of my knowledge.

London, 23 March 1953.

V. S.