Ben Okri is a Nigerian poet, novelist, and playwright. His many books and poetry collections include: Prayer for the Living, The Freedom Artist, and Rise Like Lions: Poetry for the Many. His novel The Famished Road was the recipient of the Booker Prize for Fiction.

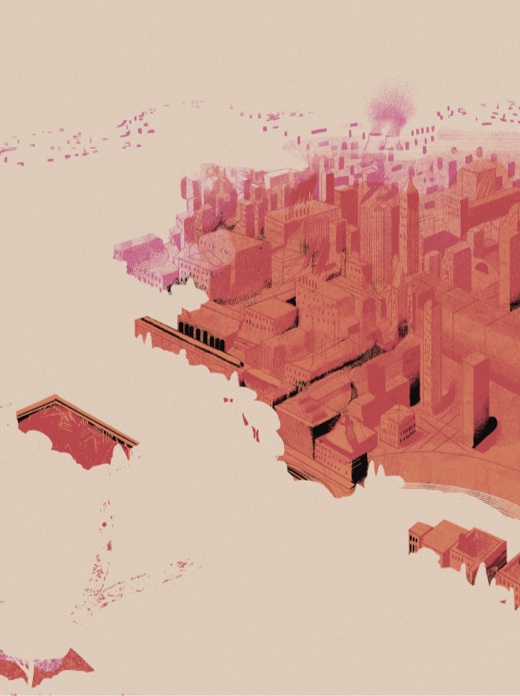

Once upon a time, in a world that no longer exists, there was a planet with vast seas, abundant forests, splendid continents, polar regions, and civilizations that evolved from remote beginnings to an age of skyscrapers and digital revolutions. Those who lived on this planet seemed to have the idea that no matter what they did life would continue there. In fewer than ten thousand years, they transformed their societies from rough conditions to ways of life so sophisticated that practically everything they did directly or indirectly contributed to the death of their planet and the devastation of human beings. They had ample evidence of the daily destruction they were wreaking on themselves, on their environment, and on their own lives, but they did not heed it. They fell into the “invisible effects” fallacy. This holds that though we do things which add up to a catastrophe, we are unable from moment to moment to see the effect of what we are doing. And because we don’t see the effect from moment to moment, we therefore think that there isn’t an effect. This fallacy enabled people to continue their suicidal relationship with the earth right up to the very last moment of its devastation. More than any other fact, this is perhaps the most startling.

On our journey across the earth—which has been silent now, according to our calculations, for twenty thousand years, and which at last is showing signs of the quiet regeneration of its forests and its seas—we came upon scattered notes and half-worked stories left behind by the last human beings in the very twilight of their history. It seems, from their notes, that their gods died a long time ago. Then towards the end, they declared the final death of God and ascended the throne. The results are unedifying. It does perhaps show that it is easier to kill off the gods or dethrone one than it is to be one. They conducted the final catastrophe of the human race as gods of an earth devoid of mystery. What is most strange is that, as you will see from these notes, they carried on through their last days in the same way they had over the years and decades prior. They altered nothing in their thoughts or behavior to try and avert the disaster that they saw coming, and which was evident every day. Maybe the final suicide of humanity was not really some momentous event that happened in the last days, the drowning of the cities and the poisoning of the air and the detonation of nuclear bombs, but was a condition caused by the mesmerism of a people chained to their past, the fatalism of a race that had accepted for centuries that it was simply unable to change. In this at least they were consistent. They perished, little by little, every day. They were killing themselves and it didn’t seem to trouble them. This is perhaps the most unheroic tragedy of all the vanished species we have encountered across the immeasurable galaxies.

The Last Solitude

The first story was found in a half-submerged house in a city that was once so flooded only spires remained visible above the waterline. We surmise that over the next three thousand years the waters receded, as the earth, with its unerring instincts, rebalanced itself in the luxury of a world without humans.

The manuscript was found intact, with some pages missing. It showed no evidence of having suffered from the detrimental effects of being submerged. Perhaps some members of the species had perfected the art of writing on a kind of paper that resisted water erosion. This could mean that there were some among them who wanted something to live beyond the universal catastrophe.

Today I woke late and observed the light fading early into the darkness. I spend my days reading. On the television it seems the masters of the earth have won complete control of the world. Everywhere they have gained power. They now form one unified chain of control across the main centers of the Western world. They control the news channels, most of the newspapers, and have penetrated our digital life and spy on our every move and listen in on our every conversation. And how did I vote in the last election? Did I vote against their candidate? Did I vote for the other candidate who wanted to make modern life more transparent and had a good program for the environment? No. And why not? Well, all the newspapers made any alternative sound like the end of the world. They frightened me. So I voted with my fear. Afterwards I regretted it. But if it were to happen again, they would get to me again. I now accept that I am a prisoner of something, but I don’t know what it is.

I wake up and drink green tea and go to the gym. I work out hard to keep my body fit and to keep my weight down. I starve through the day and measure my calorie intake and do a little yoga and breathe deeply by the window.

No matter how much I try I can’t avoid breathing in the daily death of the world. I try to avoid the news. It seems to me now that every news item brings one ever closer to death. I don’t think they mean to, but every story they report seems to help us die a little. Sometimes it is death by hopelessness. Other times it is death by despair, or indifference, or obsession. For a hundred years now, they have been saying there are too many people on the planet. At night I cannot sleep. I wonder where we will fit all the people jostling on the limited space of this earth. In my dreams I sometimes see them crowding over me, people standing side by side with nowhere to move and no air to breathe. I eat less each day because I fear that there won’t be enough food to go round. I am aware that this does not help the situation one bit, but I can’t help it.

I work at home. There are days when I do not speak to another human being. I admit that I find human beings frightening. I think that they are the most frightening thing in the whole world. They are scarier than cancer, diseases, wild animals, ghosts, or monsters. I can’t think of anything scarier than us. The world existed for hundreds of thousands of years before we came along. Then we evolved and created civilizations, and in the last hundred years, we have done more to destroy our habitat than our own worst enemies could ever have done to us. You meet a human being and they seem normal and fine and even quite harmless. But all the evil in the world has come from humans. It didn’t come from anywhere else. We hate our own kind and would leave them to die if they threatened us. We hate those who are different from us and would get rid of them if they intimidated us in any way. We have eaten this planet to extinction. I joined an organization to help save the planet not that long ago, but I found many of the people so secretly obnoxious and judgmental that it seemed to me they were part of the problem too.

Now when I meet human beings, something in me flinches. I do not know who I am meeting. I do not know their heart. People frighten me because of the things they passively allow to happen, the things they turn a blind eye to, the things they can’t be bothered to care about. We should be the blessing of the planet, should add our beauty to the earth’s beauty. But all we have done is add pollution, and waste, and evil, and destruction. We make filth everywhere with our ambitions. Everest was pristine till, with our ambition for conquest, we turned those rare heights into one of the dustbins of the world. Dolphins gag on our plastic waste. Sea turtles choke on it. The radioactive stuff we have accumulated will be toxic for thousands of years after we have vacated the earth. Day by day we believe in less and less.

My father had nothing to teach me about life except getting ahead and looking after myself first. I grew up in the aridity of that philosophy, till a day came when I had no reason to go on living. I did not care enough about looking after myself, and it got too exhausting and stressful living only to get ahead. I was not so sure that number one was how I should refer to myself. Why should I put myself ahead of others? Isn’t that what everyone else is doing, making the world a constant battleground between individuals, between states, between races, classes, age groups? We are raised with war in our hearts, with war at the depth of our dreams, and war is what we reap every day.

I watched my father grow old in the dryness of his philosophy. Nothing flowered from him. His insight didn’t get richer. He said the same things at eighty that he had said at thirty-five. He seemed to have learned little in his long sojourn on this planet. I think the philosophy we are living by is choking the life out of us. We are now barely alive as people. This is perhaps why it is easier for us to spread death in our politics and our foreign policies.

I watch the world every day and wonder what went wrong with those fine dreams that the race had in its infancy. We have over-complicated ourselves. I now have more allergies now than I had when I was a child. There are more sicknesses around, more than there ever were fifty years ago. Where are they coming from? We are proliferating diseases and illnesses. I think it is nature’s revenge for strangling her, for tampering with her, and for being divorced from her. We are isolated and rootless in our lack of belief in anything, our world ripe only for rapists and serial killers and mass murderers and the murderers of children in their schools and people in their mosques and churches. The murder at the heart of our culture has been unknowingly sanctioned by our philosophy. Meanwhile we refine our food and our tastes, we kill ourselves trying to join the rich one percent, and we despise the poor; and if we are poor ourselves, we live without hope, in council estates, succumbing to the consolation of drugs and too many children.

It’s why I have decided not to have children. Whenever I see a child, I can’t stop myself crying afterwards. I love them so much. There’s nothing I want more than a child. We human beings have abdicated the responsibility of being human. We claim the status of gods without being as wise as horses or as intelligent as flowers. Our bloated egos make us as stupid as fleas. How can one entrust a child to such a species? How can I bring such a precious being into—

Children’s Games

This one was found in a house in a big city, among the pages of a disintegrating book.

My daughter came home from school today and wanted to share the song she had learned at the nursery that morning. It was evening and we were in the living room, my husband and I. He was trying to read something, but a persistent drill somewhere outside kept making him look up. Then our daughter bounded into the living room and said:

“Shall I tell you what I learned today?”

“Yes,” I said, while thinking it was time for her to be in bed. It was nine o’clock, and still she showed no signs of slowing down.

“Okay,” she said, bright as a bell. She’s only three and has the linguistic skills of a six-year-old and more imagination than one thinks possible. Sometimes with terror I look upon her and wonder if she’s a genius who’s been born to us, some kind of freak of the mind, the blessing and the judgment of a new generation, whom we have brought forth at the most perilous time in the history of the world.

“I’ll be the teacher and you the student,” she said, and my husband and I exchanged glances. It is like this every day. Each new day she does something strange and unusually intelligent for her age, and sometimes she says something that makes us wonder if it isn’t a god speaking through her.

“All right,” my husband and I say.

Then she held a rattle in her hand. It was a blue rattle. She was smiling. She shook the rattle and started to sing. She sang with a strange smile on her face, as if she knew what she was doing, as if there was going to be a twist to it, and we had no choice but to follow her to where this journey would take her.

“What’s your name?” she asked her father.

“Daddy,” he said.

“Daddy came to school today,

Daddy came to school today,

Daddy came to school today.”

She sang the same song for me, for Mummy. Then she looked at the spot next to me. There was nothing there but the table. She looked around and saw a favorite doll whose name is Doby, and so she entered the song, and Doby came to school today. Suddenly she expanded the game, and Mozart came to school today, then it was Da Vinci came to school today, then it was Che Guevara came to school today. These figures “came to school” because pictures of them, or books with their faces, were all around, and she would pick one up and put it beside me and go back to her spot and shake the rattle and incorporate the new figure into the song. In this way Shakespeare came to school today, and Van Gogh, and Alice in her wonderland, and Winnie the Pooh, and Paddington Bear, and Picasso, and Vermeer. She stood there with an odd look in her eye, shaking the rattle and singing in the new name that had come to school today…

“I like this school,” I said, “with all these wonderful people attending.”

But she paid me no mind and with a strangely stubborn will went on shaking the rattle and seamlessly finding a new painting in the house, or a new book, each with the names of someone who came to school that morning. Then it was “that ballet came to school,” “Frida Khalo came to school,” and her imaginary friends, of whom there are about twelve—and they grow in number every day—all were obliged to come to school today. I delight in these precocious displays of my daughter, for they confirm the sense that this child of ours is some sort of a genius, whether a genius reincarnated or a genius newly born into these twilight times it is hard to say, but it is clear she is a phenomenon of some undefinable kind.

She was still in the center of the living room, the rattle shaking less and less, as she found more people who were coming to school. Her father watched nervously. He always felt about his daughter some magical condition. There were times he watched her as nervously as you might watch a seismograph recording unprecedented activity. Her sensitivity to unexpected impulses was a regular part of her personality and daily she absorbed into her mythology all the people she met and all the characters in books she encountered. She became them, she took on their names, and her assumption of personas became her diary, as it were.

Her father watched her with a mixture of wonder and nervousness that kept him on tenterhooks, with a nameless expectation arising every other moment, a state that was exhausting to him and wore him down, so that he was almost numb at the end of the day; and yet there was an electric fascination for this wunderkind of his. Never more so than today, as she stood there with her rattle and her knowing look and sly smile, singing new characters into school.

Then it seemed she had run out of people who came to school that morning. She paused, and her smile became more mysterious as she said:

“And guess who else came to school today,

Guess who else came to school today?”

“Who else came to school today?” my husband and I asked with one voice, sitting on the edge of our seats.

“Death came to school today,

Death came to school today.”

My husband and I looked at one another, in consternation, in terror. But she was shaking her rattle, with that odd look, that sly smile on her face. She raised her hands up, and the rattle now seemed to sound from above. We looked up at the ceiling.

“The death of the world came to school today,

The end of the world came to school today…”

“Honey, dear one,” I said, with a strangled note of distress in my voice, “who taught you to say that?”

“Yes, darling, who taught you that?” my husband said, standing up.

But our strange daughter held out her arms, palms facing us, commanding us to stop. We froze. It was as if she were indeed the teacher and we were the students.

“No one is going to school again,

No one is going to sch—”

We stopped her and carried her off to bed. It was the sense that she was talking prophecy that got to us. You know, out of the mouth of babes…

Two days later the flooding began in the city. Water rose suddenly, flooding the first floors. On television the politicians still denied that climate change had anything to do with it and blamed it on terrorists and socialists…

Suddenly in Venice the Ravens Sing

This was found in a house in a place once called Venice.

[Some pages are missing.]

… The barriers came down, and the waters of the world crowded in upon us, and above the ravens were wheeling. Officially the city is closed to the outside world. The lagoon is swollen so high, and its color is no longer that blue it was so famous for. It is now the color of corpses and refrigerators and the floating bodies of dead animals. We watch as the lagoon invades the streets, conquers our houses. The bells are tolling for the bodies being found. Here our deaths are lonely. We are shut up in our houses, without electricity, without water. With nothing to eat. I watch the water rising high up the houses.

But it has been rising for years, and we did not pay attention. We have been like the frog in the story, the frog in the pot who was very slowly boiled to death without knowing it.

Every day the city got hotter, the water rose micro-inch by micro-inch, and still we said there was no conclusive evidence of anything we should worry about. The scientists were divided, and their interpretations varied depending on who was sponsoring their research. I took no interest in these things. I had ceased watching the news, not wanting to be depressed by the negative things that helped sell newspapers and television programs. I thought the whole climate business was above my head, and I left it to the specialists.

But even I could see that the temperatures weren’t right. When I walked across the piazza to see my boyfriend, I would notice that the pigeons were dropping from the air, sometimes in mid-flight. I would see someone collapse near the door of San Marco. The heat was sometimes so unbearable that I wondered if I had somehow been transported to the Sahara Desert. I couldn’t make sense of the apocalyptic paradox of things: the water rising, changing color, turning a dark, sluggish green, and the heat becoming muggier, till priests were said to have expired in the midst of their sermons, and were carried out feet first to the vestibule.

Last June it snowed for a whole day. Gondoliers froze on the canal. The hospitals received at least a hundred cases of spontaneous pneumonia. Two days later it was boiling again, and many old women perished, and old men were seen crumpling over their walking sticks near the depot and all across the city. One day, not long ago, dead fishes appeared belly upwards in the canals and the lagoons. The fishermen’s nets were crammed with fishes that had been dead for some time. The odor of the lagoons became unbearable, and still no one believed that these biblical signs were in any way sinister.

Our capacity for denial is stronger than our capacity for belief. We find it easier to not face the truth. We go on living our ordinary lives while refusing to believe the overwhelming evidence that our way of life is self-destructive. A prisoner of the past, we go on doing things which we know are killing us. Worse, we believe that the inevitable conclusion of all our deeds will not come to pass. We think that somehow, at the last minute, there will be a miracle, a magical solution. We possibly even hope that factors in nature we hadn’t considered will somehow wipe clean the slate of our cultural and environmental crimes.

The trouble is that there were normal days amongst all these flashes of abnormality. There were more normal days than abnormal ones. So we went on believing that normality was the norm, and that anything abnormal was just a minor aberration. We didn’t realize then that normality was an unseen equilibrium whose condition had altered. But the dire results of that alteration weren’t apparent to us yet.

In those normal times, we watched weddings in the square. We watched brides skipping over the rising runnels of water, their white bridal dresses hitched high.

As the months went by, fewer tourists came to the city. Solitude surrounded us. Day by day the sea levels rose. At first our politicians denied it. Then they hinted that it was all the work of saboteurs. Rats grew bigger and also grew bolder. They scuttled around in daylight and didn’t run away when people appeared. It was as if they had finally claimed possession of the city. But they were not the real menace. The real menace were the smells, the politicians smoothly denying there was anything to fear, and us. We were the worst menace of all. The way we kept trying to live normally.

Our addiction to normality might be our most pernicious quality. In the mornings, when I wake, I mutter a few lines my mother taught me. I bathe, have a coffee, and walk to the office. I work as if it were the only thing in the world that mattered. In the evening I walk home. On the walk to work, I always pass the cafes in the square. I watch the waiters laying out the tables. No one is coming, but they lay out the tables as if a horde of tourists might descend on them within the hour. I read in the newspapers that yet again the American government has refused to take part in any climate change conferences and has declared, as an official statement, that climate change is a myth. I read also that all across America cities are sinking beneath the rising sea. In many cities people are having to move their possessions to higher ground; they’re living in tents and hastily constructed abodes. Apparently, the nation is in trauma. People can’t seem to believe that their normality can be so radically altered. The papers say there’s no rioting, no protesting—just a sullen mood everywhere, like a people unwilling to wake from a long dream of certainty. Reports come in from other lands. The facts are too strange to relate. Sometimes it seems as if journalists are trying to outdo each other in the strange things they report. Weirdness has become universal reality.

But each day, as I walk to work, there is a waiter I always wish to catch a glimpse of when I pass the cafes. He is not tall, like the man of the average female fantasy, and he is not thin, and his eyes are not blue. He is slight of build, and quiet, and he notices things. I saw him talking to a stray cat once. Then on another day I saw him feeding the cat. Such quiet sympathy is rare in these times, when we’re all pulling up the drawbridges of our lives…

The State Department Denies

Scattered documents floating in the capital, in which only the tips of skyscrapers are now visible.

We have put out our official statement today about the myth of climate change. The president himself, who is fundamentally and temperamentally opposed to the idea of climate change, gave the statement—with significant modifications—from the oval office. It was repeated by the news media. He especially wanted to make this statement to kill off all the wild speculation that has been driving the people into frenzies of despair. He made it clear that the wild fluctuations of nature, the persistent flooding, the accelerated number of typhoons that blast our shores, and the forest fires that devoured half of California are all natural acts and in no way suggest anything out of the ordinary. They’ve been going on for years. Strange occurrences in no way suggest Armageddon.

There was a research project set up in the department to study reports on bizarre events over the years. It turns out that every year has had its share of strange occurrences, and this is true going back a hundred years. It seems that we exaggerate the significance of the strange occurrences of our own times. We think them unique. The report was a much-needed corrective to the doom-mongering that has become fashionable. Compared to past eras abundant with terrible events, our times are very normal, even under-performing in the field of disasters. Just think of Vesuvius erupting, of Pompeii, of forest fires that used to rage for weeks, of the earlier ages of global warming that helped create the conditions for Homo sapiens to appear on the world stage; think of the climactic conditions that wiped out the woolly mammoths. It is not fashionable for scientists to say this now, or they would be crucified by the public, but in their private reports they maintain, on the whole, that fluctuations in weather conditions, fires, storms, have been part of the history of the earth for millennia. When they had religion, they blamed natural catastrophes on the wrath of God or the gods. Now they blame governments and corporations. We are the new gods. And we have decreed that there is no global warming. And even if there is, so what? We are planning our relocation to Mars. There, we’ll start again—with the chosen few. Why do people think that the earth is eternal? It is merely a coincidence that of the million planets in the universe this one is the only one stable enough to be a home for life. That stability was always fragile. Humanity was always going to evolve, and evolution means destruction. It is the law of evolution itself. We always kick the ladder from beneath us. That is the way we go forward. Pollution was the by-product of evolution, the price we paid for civilization. Those who somehow wish we had evolved differently not only deny history but also deny the tremendous benefits they have enjoyed. Can’t stand those teenage doomsayers who live in the luxury of the West, and all that implies in the destruction of other cultures, and the vast undocumented crimes of Western civilization? Do you now want, in the last moment, to somehow be absolved of all history and turn the clock back?

But what if the doomsayers are right? What if the president is leading us into the end of time itself? What if we are fiddling while the world burns? And the world is burning burning burning. It’s burning in the Amazon, burning in Australia, burning all over the United States. Cathedrals are burning and monks are setting themselves on fire and the icecaps are evaporating and the cities are aflame and there are heat waves in places where there should be snow.

What are we doing supporting a president who may be leading us to the death of all things? What kind of a job is this that obliges me to obey what is going to destroy us all? Are there no limits to duty? Deep down I do not believe this program of denial, but I am well paid, am one of the best at what I do, and here I am using my skills not only to tell what I think is a lie but to collude in the greatest lie of all, the terminal lie, the doomsday lie, the lie to end all lies.

For I can see with my own eyes that all is not well in the world. I was taking my daughter to nursery yesterday when an iguana fell from the sky right at my feet. My daughter, who is five, and still sees everything with a touch of wonder, said:

“Daddy, why are iguanas falling from the sky?”

What was I to say? Was I to give her the president’s lie, that it is nothing unusual, that it happens all the time? I tried silence, hoping her mind would find something else to interest her. But I had forgotten the unnatural persistence of a five-year-old.

“Why, Daddy, are iguanas falling from the sky? One fell just now. Look at it. But why…”

“It happens from time to time, sweetie,” I said.

“Is it God who is throwing them down? Is God angry with iguanas, Daddy?”

“No,” I said, “God is not angry with iguanas.”

“Is God angry with us?”

This stopped me in my tracks. It hit me in my solar plexus, winding me, like an unexpected Houdini punch. The kind that kills you two days later.

“What was that, sweetie?”

“Why is God angry with us?”

“I don’t think God is.”

“What have we done to make Him so angry?”

“Why do you say that, sweetie?”

She had pulled her little hand out of mine and stood there looking up at the sky. Then she screwed up her face into a puzzled frown.

“Because of the way He is throwing down the iguanas.”

I stood there at a loss. For the first time, I felt trapped in a lie that I had been spinning for the sake of raising this very same person who was exposing it with her innocent questions.

“It is not God who is throwing them down.”

“Then who is?”

I was silent again.

“And why are there so many people without homes, Daddy? Why do they all sleep in the streets?”

“Because their homes have gone under the sea,” I said, without thinking, partly out of exasperation at my own powerlessness.

“But why did the sea rise so high?”

“It’s hard to explain.”

“Are we all going under the sea, Daddy?”

For the first time I became aware of the strange, frightening intelligence of my own daughter. She seemed to be speaking with a hidden knowledge, and she was looking at me as if I knew something but wasn’t saying it. Maybe it was just the natural scepticism of children.”

“Of course we’re not all going under the sea!” I said, almost explosively.

She caught her breath. Then she gave me a strange look.

“Where did you get that funny idea?” I said, as soothingly as I could manage.

“The other kids at school.”

“Pay them no attention. They don’t know anything.”

“And do you, Daddy?”

I broke out in something of a sweat as another iguana landed at our feet. She didn’t flinch this time, just went on staring at me.

That’s when it happened.

That’s when I suddenly burst out crying and didn’t know why and couldn’t seem to stop it.

I was crouching low now, down to her level, sobbing my eyes out. People were watching us. That made it worse.

“Now, now,” my daughter said, patting my back, touching my face. “Don’t worry, Daddy. We’re all going under the sea. We’ll just have to learn to live like fishes.”

Those Deep Mines

Fragments found in what was Africa. This was a scrap from the faded pages of a magazine.

The only time I remember being happy was when I was coming out of the mines. I’d be covered in bauxite dust, my eyes rimmed with it. We went down in our ordinary clothes and canvas shoes. They would drill and the powdery stuff would be all that we would breathe, and later, up above, when I would blow my nose, it was blood that I would blow out. I thought it was all normal, and I was making money to feed my family, and no one ever told me there was another way. I always wanted to go to school, but my mother died when I was young and my father who loved her so much did not last long after she went. We had no one to look after us, and soon all seven of us found ourselves in the streets. Our relatives didn’t want to know us. Some of them tried to look after us, but they had problems of their own. Then slowly my brothers scattered, and my sister became pregnant from some man she worked for, and I never saw her again. One day a man I met asked if I wanted easy money, and I said yes. And he took me to this place far out of the city with other people on the back of trucks, and they put us in this shaft, and before I knew it we were going down into the earth. On that first day I thought I would die. I thought I was going down into hell. All the others with me were also going down for the first time. I don’t know where they found them. They all looked pale. Stray dog humans who had no homes and no families. If they died no one would notice, no one would care. We were mine-fodder. I remember the day, not long after I started, when the mine collapsed while we were inside. They didn’t come to rescue us. All the rocks and earth collapsed over us, and we had only the air of the red dangerous dust to breathe. The few of us who were alive had to dig our way out. It took almost a whole day. When we came out into the light, they fined us and then jailed us for the collapse of the mines. We were in jail when we heard about the collapse of four other mines. Then we heard about the earthquakes in the northern provinces. We heard tales of the earth splitting open and whole villages falling through the gaps. We heard of the land shifting and forests disappearing and the tides rushing over the cities and burying the tractors and the offices and the flowers. We heard of the storms that blew houses into the air. Cities were swirling in the storm, rising to the sky and scattering before crashing back down to earth. We heard of trees upside down in the wind and of the people panicking and the churches smashed by the fist of the hurricane. Then we heard that the world we knew was gone. It had all vanished into the white hole of the storm, and no one knew where it went. And it seemed that those of us who were trapped down in the mines and rotting in prison were the only ones saved. The storms blew off the roof of the prison, and for a moment the sky revealed to us our limitless freedom. Then we went out into a world in which there were only stones…

And the Gods Departed

This fragment was found wedged beneath a giant rock, a page from an unidentified book.

We were singing on the way to the shrine in the baobab forests, where the spirits are taller than the trees and where at night a blue mist hangs from the leaves of the irokos. The chattering voices of the spirits could be heard. They buzzed from below, as if speaking from the earth, but it is a trick they have, of throwing their voice, of making it take on the sound of leaves or lizards, just to confuse those who are not supposed to come into the forest. We stopped singing as we entered the forest. We had been singing of our grief. The world had gone upside down and inside out. Nothing made sense anymore, and we had been charged by the elders and the grief-stricken people to find out from the oracle and from the spirits what was going on in the world.

The rivers had gone mad, the sky no longer behaved like a sky. The rivers were boiling, but the sky sent down white powder. What did it all mean? Sometimes it was suddenly very cold and ice appeared on the ground. Then the next day it would be so hot that every living thing would be burnt, and human beings would begin dropping to the ground, and birds would crash into walls as if they could not see or as if they were dizzy with the strange changes in the air. The world was not normal anymore, and everywhere the churches were praying and singing, and things were getting worse.

Then the elders said we should perhaps go back to the old gods and the shrines and the ancestors and see what they had to tell us. So they chose me. I am one whose head was shaved by the terrible things of life. My eyes were peeled by pain and trouble. I am a penitent at the feet of a terrible life. I was surprised when they chose me. I led the procession, beating a gong through the night to drive away unwanted spirits as we walked into the depths of the forest. We went deep into the sacred forests, to where the old gods still dwell, deep in the forests where no one has ever been since the days of the shrines, which are now lost and tangled in mangrove roots, embedded in the thick forest.

We went in there fearing that the old gods and the spirits were angry with us for having abandoned them all these decades. No one could remember the last time we had come to the shrine. No one could quite remember where the shrine was. We only found it again because of clues left in children’s songs and in stories half-forgotten, which we pieced together from our different memories. In this way we made our way back to our abandoned shrine. The path was closed off and overgrown, and we had to cut out the way anew. There were large turtles there, and the mangrove swamp nearby had grown, and there were wild red flowers among the roots. They looked like blood scattered everywhere.

After much hacking at vines and climbers that had grown thick, after finding the old trail, after baulking at the strange flowers and the smooth-skinned mottled pythons that were clearly descendants of the pythons of the old shrines, after making our way through, we found that the space of the old shrine was pristine and protected, as if in secret the priests of the old gods had been coming here to keep things fresh. But this had not been so. We beheld the shrine, its freshness, with a mixture of horror and wonder.

All at once the herbalists who were with us rushed to this forest-preserved shrine and fell in prostration at the bronze images of Ogun and Eshu, the father god and the trickster god. The herbalists and priests began jabbering at once. We stood back and watched this weird transformation. The herbalists became different people, their voices much deeper, and it seemed they were in a light sleep, their faces wearing a distracted smile. Then, while we were still recovering from the shock of finding the place so intact, the shrine began to speak. The shrine spoke through the herbalists. We watched them begin to contort, to twist, to scream and howl, as if taken over by a sudden and unbearable agony. At first we feared they had been struck by snakes or bitten by vicious insects of the forest, or by scorpions: they began to thrash on the floor, their faces twisted. But then, each one began to drool and to shout out these words that no one had heard before. We were transfixed. Then my body received the communication. I don’t know how. I received it. The earth was howling through these herbalists. Then the howl of the earth seized me, and I flung myself against a tree and began to scream as if someone had plugged an electric cable into my intimate parts. Then just as suddenly, the pain stopped and a flattened moment of calm came over me. It seemed like the calm of death. And then I saw them, in their procession away from the earth. The gods were leaving. They were all leaving, and they did not look back. It was a very long procession, and I watched as they took everything with them, the secrets of the land, the icons of the ancestors, the threads and beads and links to the spirit world; they took them all with them as they steadily left our realm. Then I knew that the end had come. The beginning of the end. I wanted to join them in the procession, but I was too much a thing of the world to achieve such aerial lightness. If there was ever a moment I wished myself dead, that was it; for now that they were going, we would be marooned here—the useless witnesses of a world about to pass away—till the last breath of air. And all we could do was watch them leaving. And they left without any gesture of farewell, as if they had known for a long time that chief among our many gifts as human beings was a genius for obliterating the future…

A Vision Once I Saw

Found half-stuffed in a bottle in the forests of Peru.

We came here because we wanted a vision that would surpass the deadly negativity of the daily news. Every day some new horror. So we came out to Peru, to see some shaman a friend had recommended and took part in this rite, which culminated with the ayahuasca ceremony. Daily life was so weird, and the facts that poured at us from the papers and the television were so bizarre, we wanted to get out of it. We wanted a new vision. Everyone else just seemed to be sinking into despair and drink and drugs. Many suicides among my mates. People were just checking out before the world checked out on them. A kind of preemptive strike against death. Too much death around. Large deaths and small ones. We wanted to make a pitch for life.

The shaman was a small man with green-yellow eyes. He spoke very little, as if he distrusted words. Would that I could write this with silence. He got us to sit in a circle and took us through a ceremony that he made us swear we would not pass on. Then we each drank the potion. I lay on a large feather cushion, and at first nothing happened. Then the fabric of time and space bent, and reality altered, and I found myself on a boat on the vast sea.

It was the last boat in the world. It had a golden sail and a reddish-gold and an orange-gold sail. Three in all. The sea was vast and tinged with purple and green, and the sky was a reddish dust haze. The sky seemed to be bent over the curvature of the world. The boat had three levels, and I found myself exploring it for the first time. On one level of the boat were the last children left in the world, nine boys and nine girls. They were kept apart in separate compartments on the same level so that they wouldn’t meet and have any intercourse. They had to be kept pristine. They were the last children left in a world that had gone wrong.

On a deeper level of the boat were all the animal species left in the world, two of each. It somehow did not seem possible that all the birds and beasts fitted into that space. And in the deepest level of the boat, at the very bottom, there was something which I didn’t know. Something that was like a sound, or a light, an energy, and it was both infinite and small; and it was the secret force of the whole world, but I did not know what it was or who had put it there. The boat was being drawn by swans. Through the greatest storms, the swans drew the boat with a calm that was almost supernatural. At the side of the boat, helping the swans at their tasks, were eight octopuses.

On the third day of the boat’s journey to the place where we’d all be saved, the children started making love to one another. This was a bit horrifying, as they were not supposed to do that. They were meant to arrive at the place where we’d be saved, pristine and innocent. The sea was a purple color, and the sky was of a form never seen before, and I had no idea where we were going or what it was we were fleeing from. All I knew then was that time had altered and that perhaps time was no more.

It came to me that disease and fire and the rising sea, despair and atmospheric poisons, had overwhelmed the earth. History was over. The time of narrative was gone. All that was left were the frail dreams that floated in solitude upon the sea.

In the boat could be heard a child speaking.

“And at the end of the world,” the girl was saying, as if she were making up a new story of her own, “peace will return.”

Then the voice drifted away upon the wind.

There were some of the things we found. In a way, the girl was right. Peace had returned to the planet. It was the most peaceful and the most beautiful of the planets that we had seen in our explorations across the galaxies. It was certainly the only one that showed evidence of life having been there recently. We collected many artifacts and scraps of machines. They seemed to have used plastic, glass, and metal in most of their daily activities. From all the evidence we have, they seem to have worshipped things. They did not seem very capable of great thought or ideas as a species. They seem to have been oddly limited in their philosophy. Their images were of themselves, and they saw everything only through themselves. Unlike older civilizations we have encountered in the universe, civilizations that died out hundreds of thousands of years ago, this one showed, in the magical interlude of its existence, no especially astonishing conception of the universe, of the almost infinite possibility of it all. They seemed, on the whole, a rather parochial and tribal species, bedeviled by ideas of race and gender. Not for a single moment during their relatively short history did they grasp themselves as part of a universal order. This sense of a cosmic nobility entirely eluded them as a species.

It is perhaps this inability to rise beyond the limitation of how they saw themselves, this passionate identification with what was smallest in them, rather than what was greatest, that explains how they were unable to transcend the doom that they saw approaching them, a doom which they contributed to every day, without being able to alter it.

Perhaps a people’s capacity for change is only as great as their true conception of their spiritual patrimony. They thought themselves dust, and to dust they returned.

It gives one a pang of inexpressible sadness to know that this planet was once the home of the glory of their lives.

On this 5xxxxx eon of retrograde progress, we leave the astonishing earth behind and resume our cartography of planets in the universes that once bore witness to the serenity and the magnificence of being…