Andri Snær Magnason is an Icelandic writer and filmmaker. His latest book, On Time and Water, has been published in thirty languages, and his work has been published or performed in more than forty countries. His numerous awards include the Green Earth Book Awards Honor Book and a Phillip K. Dick Special Citation for his sci-fi novel LoveStar. His feature-length films include Dreamland and The Hero’s Journey to the Third Pole.

Philip Roughton is an award-winning translator of Icelandic literature. He earned a PhD in Comparative Literature from the University of Colorado, Boulder, and has taught medieval, modern, and world literature. His translations include works by Halldór Laxness, Jón Kalman Stefánsson, Steinunn Sigurðardóttir, and other prominent Icelandic writers.

Juan Bernabeu is an artist and illustrator trained in Valencia, Berlin, and Italy. He communicates through line and drawing, using patterns and color to bring images to life. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Smithsonian Magazine, This American Life, and elsewhere.

I’m fascinated by time. Sometimes whole years pass evoking only a few memories, while some moments are captured at such high resolution in my mind, I could zoom in and uncover endless split-second details. One such moment is happening right now. I’ve just picked up a concrete paving stone, swung it with my right hand, and let it fly in the direction of a 2020 Range Rover Vogue. I watch it spin slowly as it approaches the driver’s side window. Time is so interesting—how it’s possible to zoom in on a single moment. One corner of the stone is now touching the window, which is still intact. It will inevitably break and there will be consequences. But I did not throw the stone in haste or panic; it was a well-considered decision.

As I’m thinking this, it’s as if the paving stone has formed a small depression in the car window, not unlike how the water in a geyser expands into a sphere at the surface before it shoots into the air.

I’m not an extremist. I’m very ordinary, just to make it clear. I’ve never gotten into trouble with the law and never broke windows during my time at Árbæjarskóli, my elementary school—probably the only one in my group of friends who didn’t dare do it. I’m critical but not unfair, and sometimes I’m far too cooperative. I say “mmm-hmm” to this and that, when I should be setting clear boundaries, professionally and personally. So it wasn’t exactly like me to hurl a big stone at the side window of this car. Something major must have happened, and yes, a great deal has happened. The stone is now touching the window, and although it’s a rather new Range Rover and the damage could be considerable, I didn’t throw the stone on a whim. I threw it trusting that the damage would be worth the cost. But, because this is one of those moments I can cut down into split seconds, no harm has yet been done. The stone is perched against the window; it’s traveling at high speed but the window is still intact. There’s a man just inside the window. I can zoom in on him and see how he’s looking at the stone.

Paving stones under the brand name Jötunsteinar® (Giantstones) were first produced in Iceland in 1989 and are still being made. They’re about the size of bricks and made of durable concrete. They were used extensively around Reykjavík Harbor and later as roadstones on Austurstræti, our main street. The sturdiest ones, designed for heavy traffic, were 10 cm thick; but the paving stone that has not yet passed through the car window is 5 cm thick, as it was intended for the sidewalk in front of an apartment building.

I designed the apartment building, and it’s probably one of the ugliest apartment buildings in the country. Six others have been built using the same design.

Giantstones are directly linked to my decision to become an architect. My interest in architecture was sparked while I was working as a gardener for Hitaveita, Reykjavík’s Geothermal Power Company, when I was nineteen years old.

My foreman was a rather special man. In those days we found him strict, but today we would call his behavior “passive aggressive.” He never wanted to be asked anything; he would explain the work to us, and then we’d tiptoe around him and try to read his thoughts instead of asking questions.

One day, the foreman came and picked me up from the banal task of overseeing a group of unbearable teenage boys on a summer work program. He drove me to Vesturbær, a neighborhood on the west side of Reykjavík, and stopped at a giant, gray, clunky-looking building, one of those mysterious windowless pumping stations run by Hitaveita that one finds here and there in town. Around the building was a large uncultivated lot covered with northern dock, dandelions, broken glass, and mayweed, and the foreman explained that the time had come to get down to business and finish paving it. He pointed out a 200 m2 area at the station’s entrance that would need to be laid with the kind of paving stones that could withstand heavy loads. After that, a pathway and steps would need to be built at the building’s back entrance. I listened but didn’t really pay him much mind; I had never laid pavers before, had never been responsible for a serious project. But then he turned to me and said: “You’ll have a truck and can choose four kids to help you, and you can buy all the materials with this purchase-order book. Buy only what’s needed and nothing more. You have three weeks to finish the lot.”

I asked for the plans, but he complained that he’d been waiting for half a year for them without any sign of them being delivered and that there was no profession more useless than architecture.

“What am I supposed to do, then?”

He snapped, “Didn’t I just tell you?”

“But the pavers and sod and truckloads of other materials?”

“You have the purchase-order book! I can’t spoon-feed you everything!”

I was assigned a gray Toyota Hilux pickup truck, then went and fetched four boys who should have been picking weeds but were sleeping under a bush. I explained the project to them.

They asked, “Where are the plans?”

“We have to draft them ourselves,” I told them.

Next, I went to the concrete factory and after careful consideration decided to pave the lot with Giantstones in a fishbone pattern.

That summer changed my life. I developed a burning interest in paving and man-made environments in general. I can call to mind the walkways outside of Reykjavík’s main buildings and what paving stones were characteristic of different parts of the city, depending on when the sidewalks were laid. I can easily envision the large concrete slabs flaked with obsidian around the University of Iceland, the small cement slabs surrounding the columns of Reykjavík City Hall, the big slabs in front of the National Theater, the 30×30 cm blocks of Austurvöllur Square, the broken and ugly 40×40 cm blocks of Lækjartorg Square, and the deplorable 50×50 cm slabs that were laid all over the city for a time, backbreakers of around 40 kg each. I can also call to mind the paving in other countries: in Leeds or Palermo; the concrete-block sidewalks of Tribeca in New York City; the pedestrian streets of Copenhagen, so smooth they were practically moppable. I was like the masons in the Gary Larson cartoon strip with the caption: “Although history has long forgotten them, Lambini & Sons are generally credited with the Sistine Chapel floor.” (Everyone looks up at the ceiling. Get it?)

This happened the summer I started seeing Lilja. She took an Interrail trip with her girlfriends, having bought her ticket before we got together, and it was hard for us to say goodbye. She wandered around Europe while I worked on the paving project, and came home tanned and cuter than she’d ever been. I picked her up at the airport, and we drove the Reykjanes highway in the August night; we’d been separated for three weeks, and it was only natural that we go straight home and kiss properly. Still, I simply had to make a detour to Vesturbær to show her something unexpected and remarkable. With a twinkle in her eye, she asked, “What is it?” I drove onto the newly paved lot outside the pumping station and said, “Look!”

“What? What? What?”

“Isn’t it nice?”

“What?”

I pointed at the paving, 200 m2 of Giantstones in a fishbone pattern.

When she realized I was pointing at the pavement, she laughed so much I blushed, then she kissed me. Some girls would have just left me high and dry, but not Lilja.

“Yes, I see it now. Well done!” she said.

“Look closer,” I said. “Can’t you see? The fishbone pattern is like an endless series of hearts!”

The following year I attended the university in Aarhus in Denmark. I had intended to study landscape architecture, but I found the courses too narrow and decided to enroll in general architecture. It is of course ironic that I went into architecture because of a foreman who believed that all architects were idiots.

It all started with Giantstones, and it seems as if my interest in them is going to come full circle with the one that is now on its way through the car window. Now the window has formally broken, although the Giantstone is only halfway through it. The vehicle is parked outside a block of twenty apartments that I designed.

Lilja didn’t know that I had drawn the blueprint for this building. I didn’t flaunt it. She’d seen the building from a distance and had pointed at it and said:

“Yuck. Who designs such disgusting things?”

“I designed that disgusting thing.”

The owner of the SUV with a Giantstone crashing through its window is named Birgir, a contractor and cousin of mine who happened to have built that apartment block. Birgir, called Biggi, was the son of Birgir Sr., of BJB Contractors. Biggi contacted me soon after I returned home from my studies. We aren’t just cousins; Dad and Biggi Sr. are also old schoolmates from Reykjavík Junior College. Dad hadn’t been keen on my decision to study architecture, but now he was eager for me to get projects. I went to meet the father and son, Biggi Sr. and Biggi Jr., who were full of grandiose ideas; in fact, they dreamed of building an entire neighborhood. Biggi Sr. knew all about the contractors and the business, the politics and the building lots, whereas Biggi Jr. talked about the market, the demand, and ways to finance it all. Their idea was for twenty luxury apartments that would go for thirty to forty million krónur apiece, amounting to six hundred to eight hundred million in total turnover, and this could potentially lead to a larger business plan for three hundred apartments at eight to ten billion. After the meeting, we agreed that I would draft the blueprint for a block of twenty apartments. I went straight to my office, where my colleague, Stebbi, and I toasted and talked enthusiastically about hiring more staff; two hundred apartments was a fantastic prospect. I was very eager to land a good project and brag about it to one of my professors back in Copenhagen, to prove that it wasn’t a “professional dead end” for me to have moved back to Iceland.

Stebbi and I had just opened our architectural firm and were discussing how twenty-first-century homes might be and what it would be like to live in one after seventy years. We brainstormed: “If Corbusier had known what we know today, what sort of apartment building would he have designed?” We looked at houses built around 1930 and wondered why such dwellings were still in demand eighty years later. We explored all sorts of scenarios. Would people work more at home in the future? Would there be more or fewer TVs? And what about garages? How many garages are actually used for cars now? Couldn’t the spaces be defined differently? And what about the sharing economy? Could we have a storage room for things that people could share with an app that would go with the building? We got an artist to sketch a form that would distinguish the building’s gable. We took great pains with the details—it was the details, after all, that made the Alvar Aalto houses so long-lived. No form was used for form’s sake alone; the purpose determined the form. The roof tilted slightly, and the balconies, which captured the sun so that everyone could enjoy them better, created an interesting pattern when viewed from a distance. Practicality served the aesthetics, and vice versa. I also drew up a plan for the building lot that highlighted the environment: we used stonework, turf, and rocks, and around the entrance Giantstones would be laid in a fishbone pattern. It was a personal reference, just for Lilja.

I showed Lilja the draft. She was impressed, and we entertained the notion of moving in ourselves. We prepared a brochure and a detailed presentation for the BJB fellows. “It’s a big responsibility constructing a building that serves as infrastructure for twenty individuals or families,” I told them. “If the home is sacred, then designing such buildings is sacred work. Buildings represent public health, community; they’re the greatest monument to who we are at any given time. They’re a declaration of our culture and level of education; they’re the framework of our lives. The corner window facing Mt. Esja orients our lives, the door facing the sunny square sets the tone for the day, the arrangement determines how you meet your neighbors, how you meet people in the hallway and whether they become your friends. It matters whether the hallway is dark or bright; colors, textures, everything matters. Buildings should support people, nurture them, lift their spirits. We want those who grow up in this apartment block to go out into the world and then choose to return and raise their own children here.” It was all very lofty, and everyone at the meeting was extremely positive.

Biggi Sr. and Jr. were elated. I went with them to give presentations to the bank and the local council, and with very positive results. Biggi Jr. was so happy that he came to the architectural firm with his wife, Gugga, to ask me to design a single-family home for them. They had their eye on a particular lot and wanted to build an elegant 200 m2 house. I sketched an idea for an interesting, airy house, which they were quite happy with.

I was immersed in a proposal for a competition for a new kindergarten when Biggi Jr. called me wanting to discuss the apartment block. He had good news: they’d secured the funding and could build ten such blocks in the first phase. My heart beat fast. This was a complete game changer for our architectural firm; it would mean almost ten times our expected turnover for the coming years, and I would probably need to hire new staff. But Biggi went on: some of the building lots were in another neighborhood, in a place that I had previously said would be a ridiculous site for new construction. There were no services in the vicinity, and people would have to drive a long way to get what they needed. I asked him about the lots and when I should design these new buildings.

“We already have your blueprint,” he said.

“But the building I designed was for a specific location,” I said. “What direction will the plots be facing?”

“We don’t have much time,” said Biggi. “We should be able to use the blueprint without many changes.”

Biggi Sr. then called me and said he wanted to whittle down the design since the project had expanded so much. They’d landed a deal on windows from China that were already being shipped, so changes needed to be made. I answered professionally: “Light and shadows are a fundamental element in design considerations,” I said. “I can’t confirm anything about the windows until I know which direction the next block is going to be facing.”

But Biggi was in a time crunch and the market was growing, so he got his way. The windows from China wreaked havoc on the proportions. The units that were given floor-to-ceiling windows at the original location because they faced north toward Mt. Esja now faced west onto the motorway and toward the industrial area opposite.

Biggi called back in the middle of the week and told me that the dwellings had to be built with concrete, not with prefabricated wood elements.

“But wood was an essential part of the design,” I said. “Otherwise, the building won’t be carbon neutral. The production of concrete makes up 8 percent of global carbon emissions.”

“We’re following standards and regulations,” he replied. “We’re not going to bear the cost of saving the world.”

The wood cladding I had envisioned was out because they decided to finish the building with black transverse corrugated iron instead, and the artwork on the end wall didn’t go with it. Then he came up with a new proposal for balconies made of cheap, rough galvanized iron. I wasn’t happy, to put it mildly, and explained at length that the balconies had more than just a morphological value. But he interrupted:

“If you want to express yourself morphologically, paint a picture. We’re in competition with the nearby buildings. All that people are looking at is the price per square meter. I’m not going to lose a million on an apartment to satisfy your whims.”

“We can’t throw it all away on some imaginary plebs!”

“Árni, let me give you a little advice. Don’t talk down to me. Don’t be arrogant.”

“I’m not arrogant.”

“Morphological value?”

“Sorry, that’s just professional lingo.”

“An apartment block is an apartment block. A building is a building. We’re going to build a good, solid building. I’ve built more buildings than you’ve designed. You’ll paint yourself into a corner if you’re going to be one of those.”

“One of those?”

“Yes, one of those architects who make people chase after some bullshit. I need to build fast and sell fast. The lot is paid for and interest is ticking. If one link in the chain fails, I’ll lose everything.”

“I’m just pointing out things that people who build buildings should know.”

“This building is not your personal expression. It’s my building. You’re either with me or you’re not.”

I was looking for an answer or a way out, but Biggi Sr. beat me to the punch:

“By the way, I met your dad the other day. He’s worried about you. He says you’ve been terribly angry. You need to relax a bit.”

He patted me in a fatherly manner and spoke to me as if I were a child. I couldn’t deal with it.

“Icelanders can’t tolerate professionalism,” I murmured.

“I’m not giving you a warning,” he said, “but this is a small line of business, and if you’re hard to work with, you’ll find yourself out of luck.”

I really wanted to respond to that, and now, five years later, the Giantstone has gone halfway through the window of Biggi Jr.’s car.

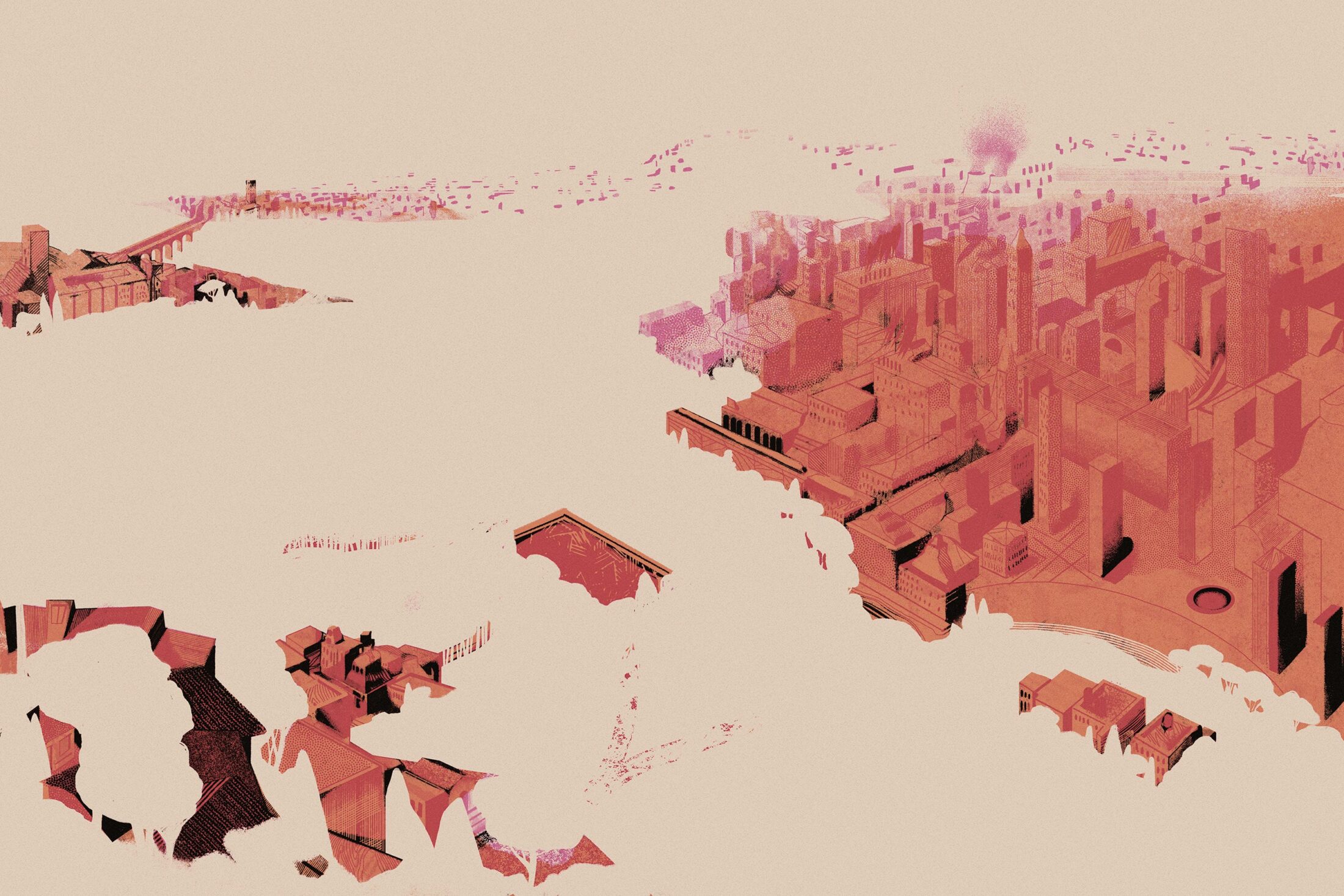

I drove around the new neighborhood, looked at the buildings emerging from the old lava field, and saw that they were as cheap as regulation standards would permit. I didn’t understand this neighborhood, why the streets were where they were, why the main road wrapped around the neighborhood, completely separating it from the surrounding nature. I didn’t understand the ideology behind it. I had studied architecture, and there were always ideologies behind everything: they characterized the periods of urbanization. All around me gray boxes rose from the ground. What was this? What was the underlying idea?

I asked the interns at the firm to change the drawings to accommodate the Chinese windows. They were furious, but I said bitterly that it would do them good to see how a dream can meet icy reality, how we need to adapt to financial realities and the demands of the client. They removed the eaves and the balconies. A week later Biggi Sr. sent me a photo of an external staircase via email, and I replied, with some surprise, “Does the building need a fire escape?”

He replied, “We want more living space in relation to the area of the building. We need to sell more square meters; we need to take the stairwell out.”

“Are you joking?”

“People pay per square meter for apartments, and no one is willing to pay for common areas. Sorry, all the buildings in the neighborhood have external stairs.”

“People pay for quality, people pay for good planning, a beautiful building, a good neighborhood.”

“Are you in this business, or am I? People fight over everything that comes on the market, and some barely manage to see a place before jumping on it. That neighborhood is popular, and there’s a shortage of housing.”

“Buildings with stairwells aren’t like buildings with external stairs. This is a totally different living space.”

“Either you do it, or we’ll send it to somebody else.”

We took the stairwell out and hung the metal staircase on the outside of the building, and in place of balconies we put an external walkway leading to the entrance of each apartment. The balcony doors were converted into main entrances, while the storage spaces in the basement were converted into an additional apartment, with a little manipulation. I asked Biggi Sr. if this was an improvement, to lug groceries, and maybe a baby carriage, up a cold, iron staircase.

“People today want to be left alone. They don’t want to have to argue about cleaning the common areas. Common areas were a socialist idea from the sixties that failed.”

The last modification was to the building’s gable: they decided to make it completely windowless. It should have had a glorious view of Bláfjöll (the Blue Mountains). I flew into a fit of rage. “Stupid crooks! The January light over Bláfjöll stays with you for a lifetime—even in hard times!”

The first apartment block arose from the wastelands on the outskirts of town. I went to the construction site only once. An Icelandic foreman was directing a group of Eastern European migrant workers, who appeared to be living in shipping containers on the lot.

I was ashamed of the building’s design, but it seemed to be in keeping with the neighborhood: incomprehensible, unambitious, and poorly conceived. Those lots didn’t appear to be subject to any particular consideration in terms of light or open areas. The parking lots were placed where I would have put gardens, the balconies faced the wrong direction, the playgrounds were barren without any shelter, and the main roads cut the neighborhoods off from nearby natural treasures. I was told that the municipality was in a hurry to sell lots as quickly as possible to fund a soccer stadium. I couldn’t point to a single building I would have liked to have designed.

A few months later we were invited to a housewarming party for friends who had just moved into a semi-detached house in that same neighborhood. I deliberately took a different route so that Lilja wouldn’t see the apartment block. We found our friends’ place. A diligent carpenter had bought the lot and sold them only the shell of the house: using a thirty-year-old blueprint drawn by an engineer, he built the main frame, added windows, and sold it to them unfinished. I had a hard time celebrating with them—“Yes, awesome, congratulations.”

We came home late that night. I lay awake and Lilja held me.

“Oh, my poor dear, you take everything so seriously,” she said.

“I know.”

“Did you find their house ugly?”

“It was so awful I could hardly stand being there. Did you see how it was placed in relation to the lot? Did you notice that the garage stole all the sunlight with a windowless wall and the living spaces were dark and narrow? Did you see how it joined with the yard, almost directly behind the TV? Did you get a feel for the acoustics?”

“They seemed happy—isn’t that what matters?”

“Is my job meaningless, then? Did I get a degree in architecture just to be at odds with everything? Imagine if you were a proofreader and the text you were checking was chock-full of mistakes, and no one noticed them but you. And nobody really cared. The new neighborhoods are full of grammatical errors.

“I can hardly name a building erected in the last ten years that I find truly important. Our generation is failing. We’re destroying the Reykjavík city center, destroying the highlands, the climate, the health care system, and the education system. We’re building ugly roads. Everything is ugly. Everything is pointless.”

Lilja held me silently.

“You need to relax,” she said finally. “Your dad’s worried about you.”

I didn’t see the apartment block with my naked eyes until after it was built, and I didn’t attend the ceremony when it was opened up to potential buyers. I saw a photo of it in a magazine ad. The Chinese-factory windows glinted, the stairwell was bleak and faced north, the railing along the new external walkway and the aluminum cladding made the building look like a prison. My name was on the ad: “New luxury apartments … by Árni Axelsson, architect.” I threw it away before Lilja came down for breakfast.

The apartments all sold immediately. I was disappointed. It didn’t seem to matter to anyone what the building looked like. Most buyers got loans of 90 percent, so Biggi and Biggi probably got the six hundred million they were aiming for. They invited me out to dinner and toasted our successful business partnership. They were happy with me; I was resourceful and my changes to the design were very efficacious in terms of construction costs. “The market seems happy with it,” said Biggi Jr. “The bank is satisfied.”

I said I wasn’t sure I had time for two hundred more apartments. They said that loading me with extra work wasn’t in the plan. They had a blueprint now that suited them and the market very well. With this project a new standard had been set in construction speed and efficiency. All I had to do was position the building on a new lot, sign the papers, and send them an invoice for 40 percent of the initial design cost.

“You’re selling content now,” said Biggi Jr. “This is of course a low-end job; later we’ll do something crazy high-end, and you can have at it. Still, you can be happy that we’ve set the trend. The market will follow us. The other contractors are still in the starting blocks with their own Árnihús.”

“Árnihús?”

“Yes, your design is called an Árnihús. I would have called it a BJBhús, but the industry likes to name buildings after their architect. Like a Sigvaldihús or a Högnahús. You’re becoming a brand. It was a triumph how we got it all approved.”

I felt sick, but didn’t say anything.

I had my partner, Stebbi, adjust the designs. One evening I found him in the conference room, scribbling away at the blueprints.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“You don’t want to know.”

“Tell me.”

“I’m still whittling down.”

“For BJB?”

“Yes.”

“They’ve gotten hold of three more lots.”

I looked over the design. “Still whittling down? More than last time?”

“Yes.”

I looked again at the design. The building was a disaster.

“What do we call this?”

“An Árnihús!”

My temper flared. “Never say that again.”

“Sorry Árni, but what are you asking?”

“What’s this style? What do we call it? It isn’t functionalist.”

Stebbi scratched his head.

“What’s the name of our period in architecture? Where are we in a historical context?

“Why was this lot chosen? Why is the building situated that way? Why are there three staircases? Why is there no window facing Bláfjöll? Can you explain that?”

“You think too much.”

“All buildings can be placed somewhere in history. The turf-and-stone cottage, the Breiðholt apartment blocks, the Norwegian timber-frame house; neoclassical, functionalist, postmodern. But what is this? Why is this building like it is, and not otherwise?”

“There’s no ideology behind it,” said Stebbi. “Build fast and cheap. Sell fast and expensive.”

“When they whittled down our design, the building became 20 percent cheaper, but housing prices have risen by 20 percent since then. It was possible to build the original block based on the price people would pay for the apartments. The difference is purely profit for Biggi and Biggi.”

“Probably.”

“We could have built the dream apartment block. With all the endowments, artwork on the end wall, wooden cladding.”

“Probably,” he said.

“It would have lasted a hundred years. This is just pathetic,” I said. “They must be making a hundred million per building. But we’re still whittling it down. What a deal—earning a lifetime’s income from twenty apartments that took half a year to build.”

Most of my dad and grandpa’s generation had no money; they built their houses themselves, had them designed and then put them up with their bare hands with help from family and friends. Even the twelve-story apartment blocks erected around 1960 were built by trade unions—printers and teachers. They did the construction themselves and put care into their work; they were building homes for themselves. BJB’s first apartment block, on the other hand, was built by a team of Polish migrant workers. For the next block, it was a few Poles but mainly Romanians, because they were cheaper. The third time, there were a few Romanians, but the majority were Moldovans. The workers are increasingly being brought in from poorer countries farther east; they’re shown little respect and care nothing about what they’re building. Biggi and Biggi don’t care either. The town council doesn’t seem to care.

I needed a concept to understand what we were doing. I needed to see my work in a historical context. In my studies, my favorite architects and those who introduced new schools of thought and new concepts abroad, as well as here in Iceland, had labels—but who was I? I had learned that architects give shape to the dominant ideology of the time—the philosophies, ideals, and new scientific discoveries—and put them into permanent form, whether in marble, wood, or metal and glass. The Breiðholt district of Reykjavík—cheap, high-quality housing built for baby boomers—was developed in line with a well-conceived social ideology that went back to the 1930s; the Workers’ Blocks on Hringbraut Road, built around that time, were the most modern apartments in the world for the poorest people in Europe. When the functionalist and futuristic ideals of the Bauhaus School were unfolding in Germany, many Icelanders were still living in turf-and-stone cottages. With the arrival of functionalism to Iceland—which came almost straight from Bauhaus—the Norðurmýri neighborhood was built, and many who moved there took a leap into the future, skipping eight hundred years of European architecture. “Turf House to Bauhaus” was the name of my final thesis in Aarhus. I understood the architect to be an influencer of societies, manifesting change and progress, the one who designs the outlines of society.

I looked over the neighborhood that was now under construction and tried to get my head around it. What ideology prevailed now?

The Giantstone is still on its way through the window, moving very slowly: so slowly I can see the expressions of the people inside the car. To Biggi’s right is Gugga, his wife. She’s a bit wide-eyed and open-mouthed—as if someone had just thrown a paving stone through the window of her car.

The high-end project Biggi Jr. promised me had just arrived on my desk. “A project that would satisfy my ambition.” It was the house he had been planning for himself and his family, but the design had swelled a bit. Biggi Jr. came to me after the fourth apartment block was finished, a good deal more confident than last time. He was in a light mood, and his clothes were more expensive than when the first block was built.

He came with his wife, Gugga, whom I knew. She grew up in the same neighborhood as me. She was called Gugga Truck when I was in elementary school. She was no truck; she was rather delicate and pretty. But her family had just moved from the village of Raufarhöfn, and her dad shuttled her to school in a huge truck. He only had to bring her once and the name stuck with her throughout elementary school.

Biggi Jr. and his wife had great ambitions for their single-family home. In my original draft, the house was just over 200 m2, but now they wanted it to be 650 m2. It was to be built on an oceanfront lot, and they’d just bought and demolished the house that had been there.

“We hope we can make a house that will be featured in Dezeen,” said Gugga.

She was very sincere about this. Maybe she was eager to show that she was successful; it must have really hurt her, having been called Gugga Truck.

“This should make up for the fact that the block didn’t turn out as you requested,” Biggi Jr. said cheerfully.

For the next few months, I was in constant contact with them. As apartment blocks seven and eight were going through the municipality’s approval process, Biggi Jr. kept me informed of the details so I could adjust the blueprint to the lots; meanwhile, Gugga called me to go over concepts and materials for their new house.

Biggi called me that morning to go over the seventh apartment block one more time. He had learned from his experience with the other buildings how to be more cost-effective. They could, for example, reduce the number of electrical connections by 10 percent, or use plastic parquet floors instead of wooden ones.

“Plastic is much more durable for families with children,” said Biggi.

The bathrooms should be painted instead of tiled. Buyers should have the “freedom” to have a wardrobe in the bedroom instead of a closet. One run-through with me for fifteen thousand krónur per hour would spare him maybe two million in construction costs.

Later that day, Gugga called to discuss some rare tiles for the bathrooms that needed to be special-ordered from South America, and also how to position the bathtub in the third bathroom so that it would look out toward Snæfellsjökull. She asked if I could go with her to Denmark to choose a special faucet and then to Italy to have a kitchen custom-built for the house—all expenses paid, of course. For the vestibule, she wanted custom-cut stone from Morocco that she’d seen in a magazine, and leather tiles from Spain on the walls to improve the house’s acoustics. She also had a special wood in mind for the floor, a rare Asian variety, and asked if I knew where it could be ordered.

“But you have children. Isn’t a plastic parquet floor what you want?”

She laughed, finding me very funny.

As I was writing up invoices, I noticed that I’d spent more time on their bathroom than I had on the entire apartment block, and most of that time had gone into cutting out elements the two Biggis felt were unnecessary expenditures.

I had designed all kinds of homes—single-unit houses, townhouses, apartment buildings—and I was aware that there was a certain growing inequality in our society, but this was the first time I had the same client for such extremely different buildings.

I was like a thief. I had gone through the apartment block and practically emptied it: reduced the wiring, thinned out the walls, installed cheaper doors, went over everything with thinning shears. Meanwhile, Biggi and Gugga wanted to be able to control the lights, heating, and curtains in their new home with an app on their phones.

I’d never seen my job so clearly. I was a cat’s-paw, transferring quality from one person to another. As I was gutting the apartment block, real estate prices were rising, and in the end only a skeleton remained: that’s what was left when the apex predator, the contractor and the investor, had eaten their fill.

And suddenly I realized the context. The apartment block wasn’t a building, but an ideological system specially designed to transfer wealth from one person to another. There was nothing remarkable about this block, no reason why Biggi was better at building it than anyone else: the poorest workers in Europe could build it easily. There was no reason that Biggi, a temporary middleman, should be allowed to walk away with a hundred million in profit. “My” apartment block was specially designed to make one person very wealthy off the backs of twenty families. Everything that could have been in it had been stuffed into a 30 m2 bathroom or a gold-plated kitchen in a house with a view of the Snæfellsjökull glacier. I serve the prevailing ideology and give it form; I create the space. If society is based on inequality, then it’s I who make inequality visible. I plunder the apartment blocks of the common people while stuffing as much luxury as I can into a 650 m2 single-family residence and create an untouchable elite, of which Biggi and Gugga Truck will be members as soon as I get them into Dezeen. I’m a tool. In the Middle Ages I would have designed castles, servants’ quarters, and moats. In the Soviet Union, it would have been residential buildings and Stalin’s Palace of Culture and Science. In Egypt, pyramids. In Sweden, I would have designed public housing and concrete brutalist cultural institutions. In Germany, it was Albert Speer who actualized these ideals. In the United States, Raymond Hood designed the Rockefeller Center, and Yamasaki designed the World Trade Center—but he also designed the Pruitt-Igoe complex in St. Louis, which became a breeding ground for unhappiness and despair, like Blok P in Greenland, where people were piled when villages were emptied in the interest of efficiency and colonial “kindness.”

I think I became quite depressed around that time. Lilja and I were starting to drift apart. We had to pick up something at the Smáralind shopping mall, and I told her I didn’t want to go.

“We need to buy a present for your father,” she said. “You’re lucky I’m going with you.”

We drove along the Reykjanes highway and I looked at the road, the interchanges, the rows of cars, the structures that had sprung up all around in recent years. And I saw it all as just a shell.

“The Smáralind mall looks like a penis from above,” I said.

“Yes,” she said. “That’s an old joke.”

“Do you think the architect was in revolt? Do you think he knew in his heart that the mall was badly designed, a lousy idea?”

“I find that unlikely,” she said.

“The first suburbs were built to bring people out of dirty cities and closer to nature; folks were longing for beautiful green spaces. This ideology was based on a dream of a healthy society with access to nature and the outdoors. But here, a suburb has been built without any sign of nature. The local government didn’t want to lose good building sites to greenery. Instead of a forest or pond or garden at the center of the neighborhood, there’s a shopping mall that looks like a penis from above. They’ve arranged gray boxes around the mall. That’s the ideology. People should be consumers, they should owe the bank, they should keep the economy going, settle for things stripped of quality, and provide profit to a small group of rich people. That’s the zeitgeist of our times. Utter futility. People should shop until they’re fat, depressed, and sick, and then let the pharmaceutical companies and private hospitals take them in as raw materials for further profit.”

Lilja listened silently, then sighed heavily. “You don’t need to teach me anything.”

“I design inequality, I design buildings for neighborhoods that are made to create social isolation, increase private car traffic and consumption. I’m destroying my city and destroying the earth. The world we see is not the whole world. Everything has been whittled away so that someone can shit in a gold toilet—if not here, then somewhere in the world. And it’s all built with raw materials plundered from the earth, which we’re stealing from our children.”

“Just let me out here,” said Lilja. “I’ll have my mom pick me up. You go buy your dad’s present.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Just let me out,” she said.

I let her out at the bus stop and drove off in silence. Biggi called me and asked if I could meet him at apartment block number seven.

“The building is going on the market. It’s time to get a photo of you in front of an Árnihús. And I have a PR person who’s going to send photos of our villa to Dezeen.”

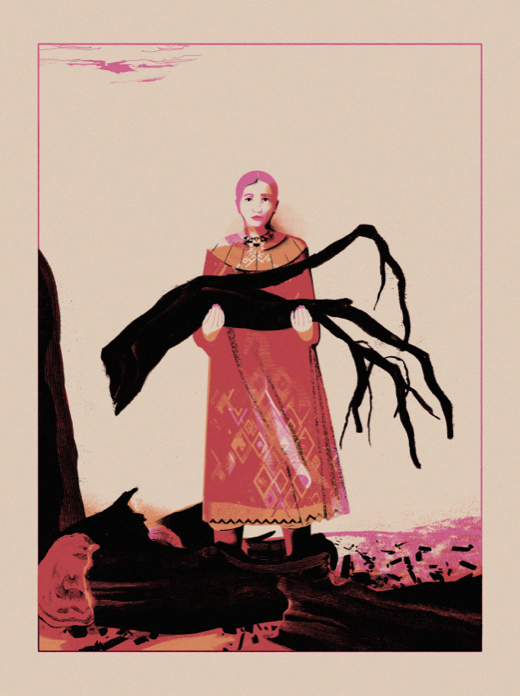

I drove aimlessly around the neighborhood in search of the building, but it wasn’t hard to find. It pained me to see the balconies, the corrugated iron; to think about the people who would take a forty-year loan to live there. The building clearly provided no shelter from the north wind; I pitied the children who would grow up there. Outside, workers were paving the lot. A pallet of Giantstones stood there in front of the building. They had begun laying the stones, but not in a fishbone pattern. I stopped the car and walked over to them, trying to explain that the pattern should be different. They didn’t understand me and obviously didn’t care. Why should they care? I took one of the Giantstones and was going to show them the pattern, how it was actually heart-shaped, but then thought it would be inappropriate: there was no heart in this project.

I was holding the stone when Biggi Jr. drove up. It was so logical to release it into the air, letting gravity take it on its natural course. And now as it’s passing through the window and licking the tip of Biggi’s nose, I can’t say what will happen next.