Cal Flyn is a Scottish author and journalist. Her books include Thicker Than Water, a Times book of the year; and Islands of Abandonment, shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize, the British Academy Book Prize, and the Baillie Gifford Prize for nonfiction. Cal’s journalistic writing has been published in Granta, The Sunday Times Magazine, Telegraph Magazine, The Economist and others. She is the deputy editor of Five Books, and a regular contributor to The Guardian.

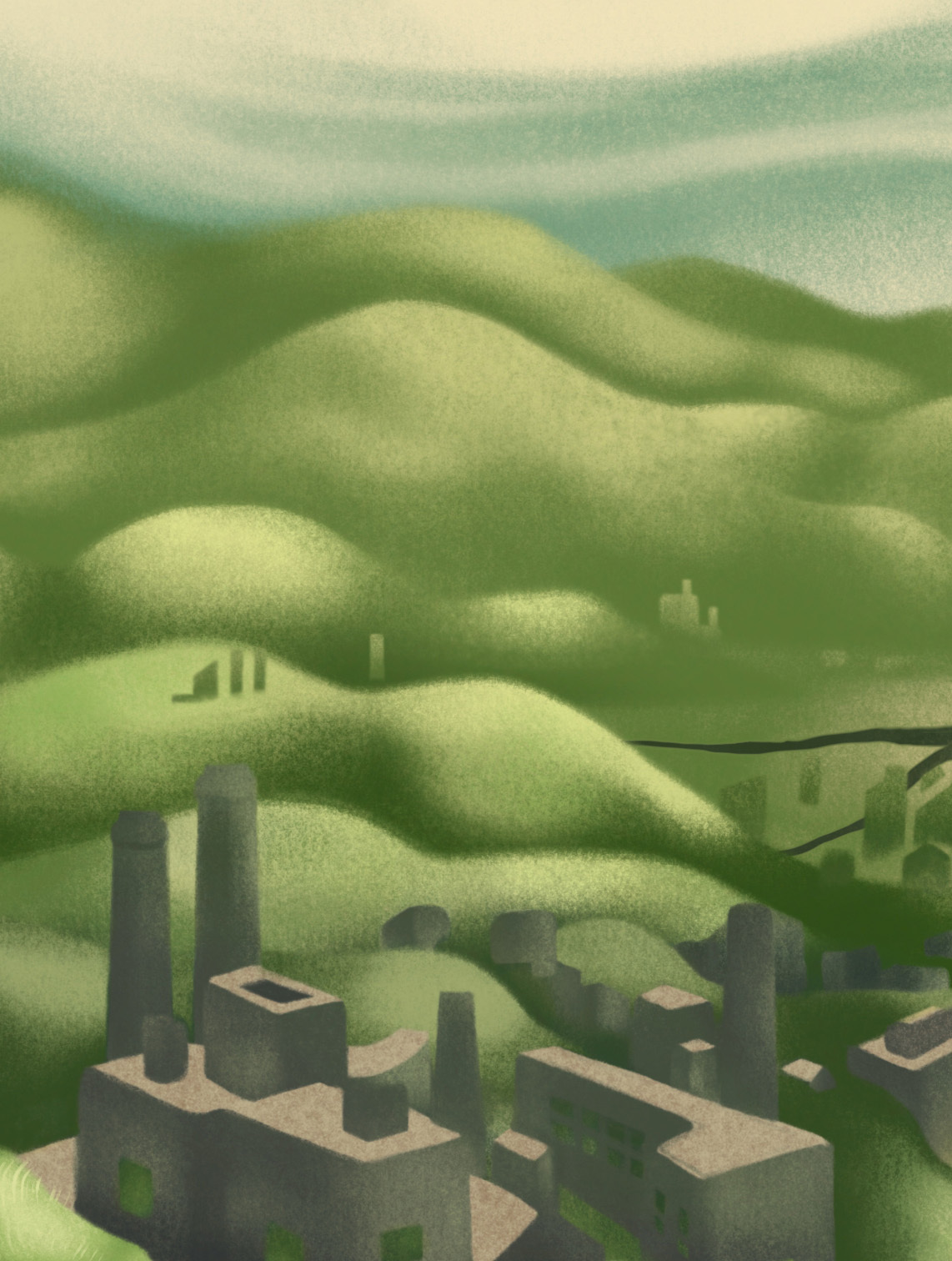

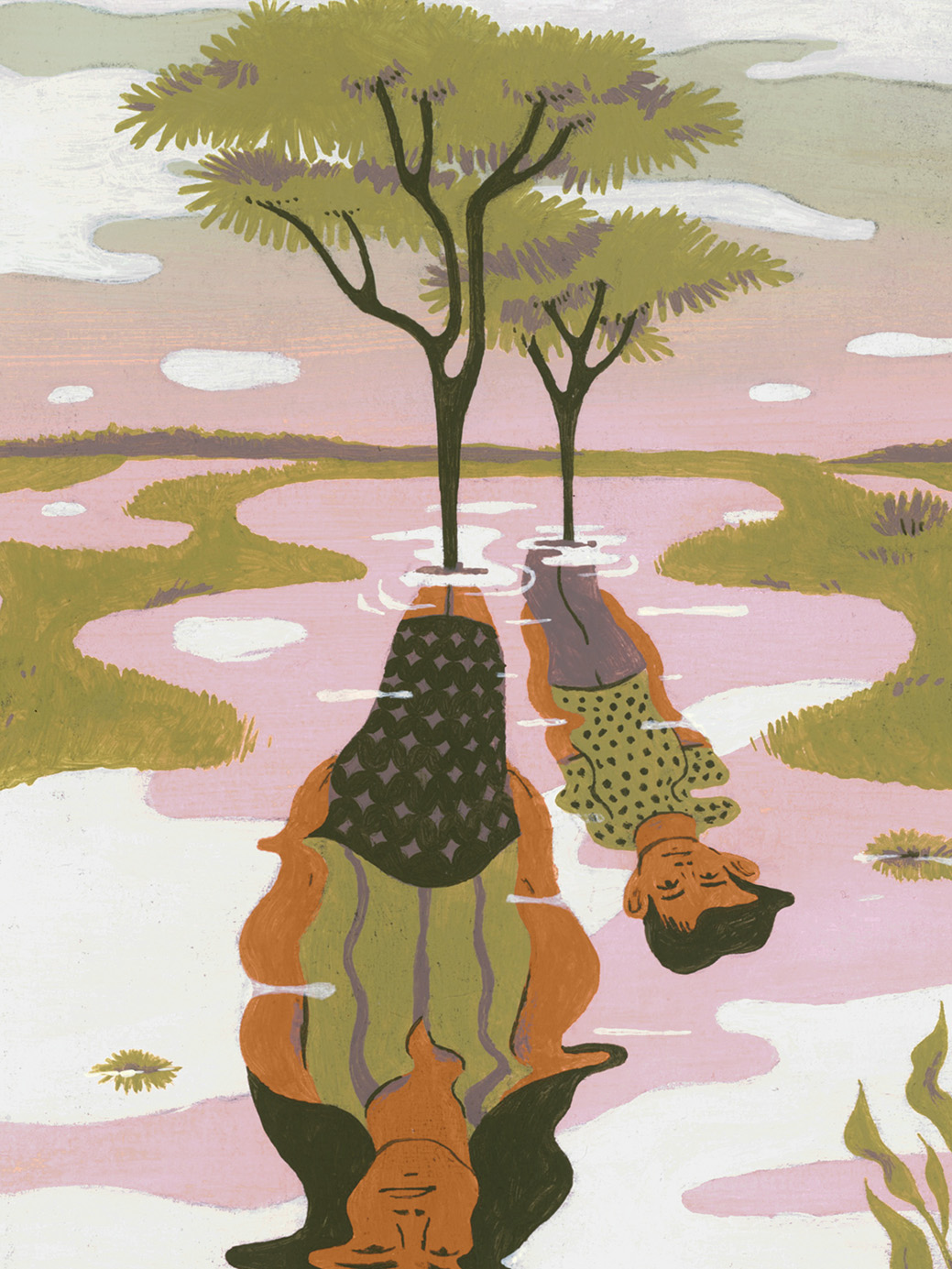

George Outhwaite is a painter from the Midlands, UK, interested in how nature and industry coexist in the countryside. His work has appeared in Protean Magazine.

As plants and animals migrate northwards on an unprecedented scale, Cal Flyn observes new species of butterflies arriving in Scotland’s Orkney Islands and faces the haunting knowledge that some voices are rising as others fade away.

Scotland’s Orkney Islands, where I live, occupy a kind of climatic border zone. I grew up only a hundred miles or so to the south, but the difference between the two points is marked. As one travels north, one passes from a landscape of rough pasture, woodland, and fertile floodplain into the smooth, rolling countenance of peatland and blanket bog.

The few trees that do grow here in Orkney tend to cower and hunch, braced against the wind. Fields are tussocked and marshy, rimmed with reeds. The higher ground wears a sack cloth of heather and thin grasses, sometimes a creeping willow that grows not up but across, wreathing the earth in catkins, clambering over boulders. Gardens, too, tend towards the spartan. The weather is cold enough and wild enough that many popular British bedding plants struggle to survive.

It is partly thanks to this harsher climate and partly due to our separation from mainland Scotland by the treacherous Pentland Firth, a six-mile strait notorious for tidal races and swirling whirlpools, that we have relatively few animal species too. There are no foxes, no badgers, no squirrels, no snakes. Our biggest land animal is the hare.

Though at first, when I arrived, I grieved for the loss of those not present, I’ve come to appreciate the more intimate relationship we have with those species that do live alongside us: our fellow islanders. These are our familiars. We see them in all their garb, note their seasonal comings and goings.

Among their number are seven resident butterflies. There is the large white butterfly, with strong, bleach-white wings, whose caterpillars feed on the sea kale that grows in silvered clumps along the coast. The green-veined white butterfly—similar but more delicate in form—with underwings of vivid lime. The large heath butterfly: a frequenter of peat bogs, in neutral tones of auburn and taupe. The dark green fritillary butterfly, with its mottled wings. The violet flash of the common blue butterfly, lover of clover and bird’s-foot trefoil. And of course, the ubiquitous meadow brown and small tortoiseshell butterflies, found all across the British Isles, but no less beautiful for that.

The technicolor peacock butterfly, with its bright sequined wings, fetches up here every few years, breeds perhaps, dies off again. A couple of glamorous, jet-setting migrant species—the red admiral and the painted lady—blow through on occasion too, on their way elsewhere. But these seven species are the Orcadian baseline, and one might count them off as if from an attendance list. In fact, people do. Here, as all across the UK, and in many countries around the world, butterfly enthusiasts are constantly recording the presence—or lack thereof—of butterflies in their local patches, like so many schoolteachers taking attendance.

These records, the compiling of which represents an act of environmental devotion on a grand scale, often serve as the basis of scientific inquiry. Through their analysis we might observe population-wide trends: the dates of first laying eggs, of hatching, of building their chrysalides. We might keep track of their total numbers, or at least make an educated guess at them. We might observe booms and busts, and thereby trace the effects further up or down the food chain.

Butterflies are highly sensitive to temperature, weather conditions, and other environmental facts. They have a short lifespan and are highly mobile. They are also easy to spot and identify and record on a map. As a result, butterflies have come to offer a useful proxy for scientists interested in how the world’s species as a whole are responding to the changing climate: the reshuffling of life as a whole.

Any changes in their locations or behaviors are interesting not only for what that says about their personal journey, as individual insects or species, but for what they might signify of greater, more universal changes.

In 2019, there was a new girl in town. She was a pretty little thing, with ragged amber wings speckled with cinders. This was the comma butterfly, spotted for the first and, so far, only time in these islands.

It’s not unusual for new species to pitch up here, unannounced. It happens among birds too: on a routine passage, they are blown off course and end up stranded on the nearest dry land. These lost souls are generally known as “vagrants”—that is, one who wanders from place to place, without permanent home—and are usually one-offs. But in the case of the comma butterfly, we have reason to suspect this might be the first of an incoming flood: a brave pioneer venturing into the unknown.

For, despite the comma’s delicate appearance, she and her kind have been staging a most audacious land grab over recent years. One can follow it through the records quite easily. In the 1970s, the comma butterflies were resident only in the southern half of Britain, with a range extending through central England but not farther. Two decades later, they had colonized vast tracts of new land, expanding their territory north by more than 130 miles to the Scottish capital, Edinburgh. And in the years hence, they have edged even farther—through Fife, Aberdeenshire, the Highlands. It was assumed they would come to a halt at the north coast, like so many others. But then, there she was: a comma butterfly in Orkney. Unmistakable. Just the one, so far. Or, one that we know of. But it only takes a few wandering vagrants to happen upon one another and there’s your colony.

And the comma has not been the only new arrival. Earlier this year Orkney recorded its first ever speckled wood butterfly: a neat, rather dowdy little insect wearing dappled brown wings with pale fringing along the edges. It, too, has spent an expansionist few decades, repossessing old lands throughout Scotland and laying claim to new ones. Butterflies, it seems, are on the march.

One summer’s day you might wander down to the archipelago’s southernmost reaches—South Ronaldsay’s rocky headland—to look out across the firth. On a clear day, you can see the shadow of the cliffs opposite, the crags picked out in black: mainland Scotland. With the wind in the right direction, it’s not such a leap. Even for a tiny, flittering insect. You might stand there for a while, in wait, like a welcoming party.

All around us, the natural world is in flux. As temperatures rise, countless species are marching northwards into new lands. Tree lines sweep the land in slow motion, whole forests hitching up their hemlines and advancing. Species of all kinds trade seats, jostle for position, abandon longtime homes in the hopes of a better life elsewhere.

Around half of all the world’s plants and animals are believed to be shifting their ranges in response to man-made climate change. Land-based species inch polewards at a rate of ten miles a decade—that’s four and a half meters a day—while others climb heavenward, up the nearest peak, thus gaining altitude and finding chill air at higher elevations.

Tropical ecosystems seem particularly affected; compared to the inhabitants of temperate regions, tropical species tend to live within narrow thermal windows, which do not vary with the seasons. In 2012, researchers revisited the site of an 1802 study by Alexander von Humboldt on a glacier-capped volcano in Ecuador; fifty-one species of plant had shifted upslope by an average of 675 meters during the intervening decades. Others have found a similar pattern in reptiles and amphibians in Madagascar, birds in the Andes, forests in Siberia.

Butterflies, it seems, are on the march.

Last year, scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, noted that myriad tropical species were already spreading northwards through the United States. “While some may welcome manatees and sea turtles,” they noted drolly, “few look forward to the spread of Burmese pythons.” A key disease-spreading mosquito, Aedes aegypti, has expanded 150 miles northwards per year through the US and is on schedule to reach Chicago by 2050.

The pattern is, if anything, even more notable in the sea, partly because the ocean absorbs most of the excess heat, and partly because sea creatures are more sensitive to temperature change. The Atlantic cod, just as one example, has shifted northwards by more than 125 miles in the last ten years. Researchers at Rutgers University have forecast that, if current rates of emissions do not slow, eleven species of fish will see their habitable range shift north by more than 1,000 miles by 2100; more than a hundred other species will see theirs shift by more than 500 miles over the same period.

This, among other things, will cause havoc for the fishing industry. Some fisheries in the tropics are expected to decline by 40 percent or more as fish populations flee for cooler waters. Blue whiting, capelin, and sea bass have all moved far enough already to have forced fishermen to change their patterns. And the North Atlantic right whale, one of the most endangered animals on the planet, has been changing its range—migrating north of Nova Scotia into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, right into the path of one of the world’s busiest shipping channels. One year, seventeen of them perished after becoming tangled in nets or being struck by vessels.

Among butterflies, climate change is considered one of the major drivers in the collapse of the Western monarch butterfly—known for its vast, shivering colonies of overwintering insects that amass as shrouds over trees in Mexico—just as its sole food plant, milkweed, also shifts in distribution.

Movement of species, in itself, is not a new phenomenon. Or, not exactly. If one zooms out, considers the passage of eons, then the world’s species have always been in constant motion, like an enormous game of musical chairs. There have always been winners and losers: once ubiquitous creatures who now cling on in only the tiniest pockets; the formerly meek now suddenly come into ascendance. What has changed is the timescale. Tree migration, or the gradually shifting patterns of forest across the landscape, has traditionally moved slowly; fossil and pollen records suggest forests shifted northwards after the last ice age at around 50 kilometers per century. Today, the contiguous United States might expect to see much of its aspen, maple, birch, and beech forests retreat beyond the Canadian border by 2070.

It may, too, transpire that the change will be too fast, too soon; that species and even entire ecosystems will fail to shift quickly enough to survive. Some findings already suggest that forests may be climbing mountainsides at only a fraction of the speed they might require.

And even those agile enough to move might find their way blocked. Cities, highways, rivers, ravines, oceans all get in the way—each might represent an impossible obstacle to breach. Arctic species may find there is, already, no farther “north” to retreat to. Montane species may have already topped out, arid plains stretching between them and their nearest alternative peak.

According to Chris D. Thomas, an evolutionary biologist at the University of York, we might expect 10 percent of all land species to perish due to the challenges of climate change. The only “realistic conservation option” we have for affected species, he argues in his book Inheritors of the Earth: How Nature Is Thriving in an Age of Extinction, is to pick them up and put them down again in a spot where the future climate might be kinder to them.

For every comma and speckled wood expanding into unknown territory, there are other species who are proving not quite so adaptable. In the UK, the pearl-bordered fritillary and the Duke of Burgundy butterflies are struggling to maintain even toeholds in a world where habitat loss, population fragmentation, and overgrazing have already seen their numbers decimated.

If anyone knows about the state of butterflies in the Orkney Islands, it is Sydney Gauld. Sydney is one of these faithful recorders of the natural world, a creator and keeper of precious data. He specializes in lepidoptera: winged insects like butterflies and moths. A year or two ago, I met him one blustery morning at his farm near Kirkwall to watch him open a moth trap and record its contents, an activity he does regularly throughout the year.

A moth trap is just what it sounds like. It’s like a lobster creel for insects. It takes the form of a box with a one-way entrance, with a light for a lure. Sydney will set his up in the evening, leave the beam shining up into the sky all night, and wait for the moths to flood in all through the darkest hours. Come morning, he will open the lid to reveal a casket of wonders: dozens of small, winged creatures waiting to be examined, then set free.

I watched him unpack the spoils: in the recesses of about a half-dozen cardboard eggboxes were nestled dozens of moths, groggy with the cold, their wings tightly folded. He scrutinized each specimen in turn, identifying them quickly, tallying their numbers, and occasionally transferring one into a small plastic vial for closer inspection. They were perfect, bejeweled: one glinting-gold insect was called, perfectly, the “burnished brass.” Others were named for soft furnishings: carpets, brocades, ermines, muslins. It was a lesson, for me, in the importance of close attention, and the beauty and plenty that might be found in the minute gradations of life.

The contents of these treasure troves change with the passage of the seasons. That morning we’d hit a rich seam of poplar hawkmoths: unusually large, cartoonish creatures with curling abdomens and outsized wings of a delicate taupe. Sydney lifted one gently with the end of a pencil and dislodged it with a flick onto my finger, where it clung on for dear life with tiny grappling hooks, which produced a faintly disturbing sensation when it moved.

Sydney’s been doing this since he was a boy. He has a good sense of how these various species rise and fall over the course of a year—what’s new, what’s notable. When I call him up now to ask him about the new arrivals, he’s more circumspect about the new butterfly arrivals than I might have expected—more hesitant to make grand conclusions from initial sightings.

There isn’t a year that goes by when a new species isn’t added to the regional list, he tells me. The problem is in the interpretation: “It’s difficult to be definitive. Have we only just noticed them? Or are they genuinely moving?”

A northwards expansion seems more clear-cut in some cases than others. Take, for example, the poplar hawkmoth that I’d admired at such close quarters. “It’s big,” said Sydney. “Its caterpillars are big. You wouldn’t think we’d miss them.” Bar the occasional vagrant, they didn’t show up in moth traps on the islands until the 1990s. Then, they appeared down in South Ronaldsay and only later spread across the other islands of the archipelago, one by one. A cut-and-dried example of a colonization, if ever there was one.

Illustration by George Outhwaite

But not every species is so bold. The dark green fritillary butterfly, once common across the islands, was nearly wiped out over the course of a single poor summer and now survives in the dunes of a single beach on the small island of Burray. They don’t like crossing water, says Sydney. Not ideal for an island land grab. “Others, if found in a particular area, won’t move more than a couple of yards. That’s how limited their range is. If they’re in a wee hollow, that’s it. That’s their world.”

Compare this homebird to the globe-trotting painted lady butterfly, which migrates en masse each year from North Africa to the Arctic Circle and back again, a distance so vast that no single butterfly could see both the starting point and end point. A migration is a multigenerational event, a hundred thousand insects blowing like a cloud over the land, for thousands of miles, each individual viewing only a tiny portion of its species’ great journey.

In other words: butterflies are many and multivarious. One has to be careful not to overgeneralize from a few sparse sightings. But it does seem that many species of butterfly are moving their home territory—and that those able to do so are likely to be the species that benefit most from the changing of the guard.

The butterfly and moth records tell us not only where certain species might be found, but when. As winter rolls into spring, and spring into summer, the assortment of species that turn up in a moth trap will cycle with the seasons. The December moth, for example, brushes shoulders with the winter moth and the mottled umber and the pale brindled beauty. By late summer, none of these are to be found, but instead perhaps rosy rustics, barred chestnuts, small phoenixes, canary-shouldered thorns.

This is the case not only for insects, of course, but for all forms of life. As the seabirds return to the cliffs to breed, we might look for the blooming of the sea thrift and the tiny white flowers of scurvy grass.

By taking note of the changing chords of the life around us, we might come to appreciate how the natural year functions as a fugue, a chiming in of voices in staggered succession, each season coming together in polyphonic crescendo before falling away: a chorus of summer replaced in turn with the growing cacophony of autumn. On it goes, in a never-ending cycle. We call this phenology: the study of the timing of natural events. To come into contact, species must neighbor one another not only in space but in time.

When species have evolved together over thousands of years, their codependence can be tightly intertwined with the seasons: Butterflies might emerge from their chrysalides just in time to feed upon a specific flower just come into bloom. A caterpillar might feed most efficiently on the sweet, soft growth of spring. The orange-tip butterfly, for example, feeds only on the flowers and seedpods of its host plants—the availability of this foodstuff forms a crucial, monthlong window, and the orange-tip will, as a result, fly relatively early in the year compared to other butterflies. Swedish researchers have found that the butterflies are flying earlier, in conjunction with earlier flowering seen in their host plants.

The orange-tip, in other words, is adjusting its body clock to fit in with its necessary counterpart species. But not all forms of wildlife will be so adaptable. In Hokkaido, Japan, for example, researchers have shown that early snowmelt can cause early flowering in wild plants, too early for their wild bee pollinators to have emerged from hibernation. Without pollinators, the flowers cannot produce seeds.

The onset of rapid climate change thus presents a second risk factor: species that rely upon one another might fall out of phenological sync. These are nature’s missed connections. Dire ecological consequences will follow for those lonely hearts who might lose their mutually beneficial relationships because they have turned up at the arranged spot at exactly the wrong moment.

Conversely, some species will brush up alongside others for the first time. Researchers have warned that this may bring us all into contact with new, dangerous viruses. Food chains, mutualisms, and other symbioses will have to be worked out anew. There will, inevitably, be heavy losses, as blossom bursts fruitlessly into bloom before the butterflies have arrived to feed on its nectar, or as herds of hungry herbivores arrive before the growth of spring grass. This is, in effect, a complete retooling of the planet’s complex workings. Over time, as Prof. Thomas has argued, the compounding changes of the coming centuries will effectively constitute “a new biological world order.”

That’s the signal we’re receiving. But for now, I can still enjoy the noise. While I was writing this essay, I traveled to the south of England for a work engagement. This required a journey of around 800 miles, and a forward jump in time—phenologically speaking, at least. Down in Devon, the daffodils were already long wilted, and the bluebells were in bloom, sweeping the wooded glades with a haze of blue-violet. In the evening, the low sun cast long shafts of sunlight between the trees, through which butterflies drifted like dust motes, confetti from a wedding. The air was fragrant with the scent of wild garlic, and percussive with the drumming of woodpeckers. Fallow deer shifted through the woodland at the end of the field.

Upon a cuckoo flower—a wildflower with petals of the palest lilac—alighted a small butterfly. Its outer wings were mottled with the mint green of lichen, but opened to reveal a swatch of bright color: an orange-tip butterfly. Common enough this far south.

A week later, on my way north, I see one for the first time in the field that neighbors my parents’ house. This is the Highlands of Scotland: 57º north. Hello, I say. Fancy seeing you here.

Tomorrow I will make the final stage of my return journey. It involves a ninety-minute ferry journey, an arduous trip for a small insect. We have cuckoo flowers in Orkney, but no orange-tips. Still, that might not be true for long.