Sumana Roy is the author of How I Became a Tree, Missing: A Novel, Out of Syllabus: Poems, and My Mother’s Lover and Other Stories. Her poems, essays, and stories have been published in Granta, Guernica, Prairie Schooner, LARB, The Common, Catapult, The Journal of South Asian Studies, American Book Review, among other places. She is currently Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University, India.

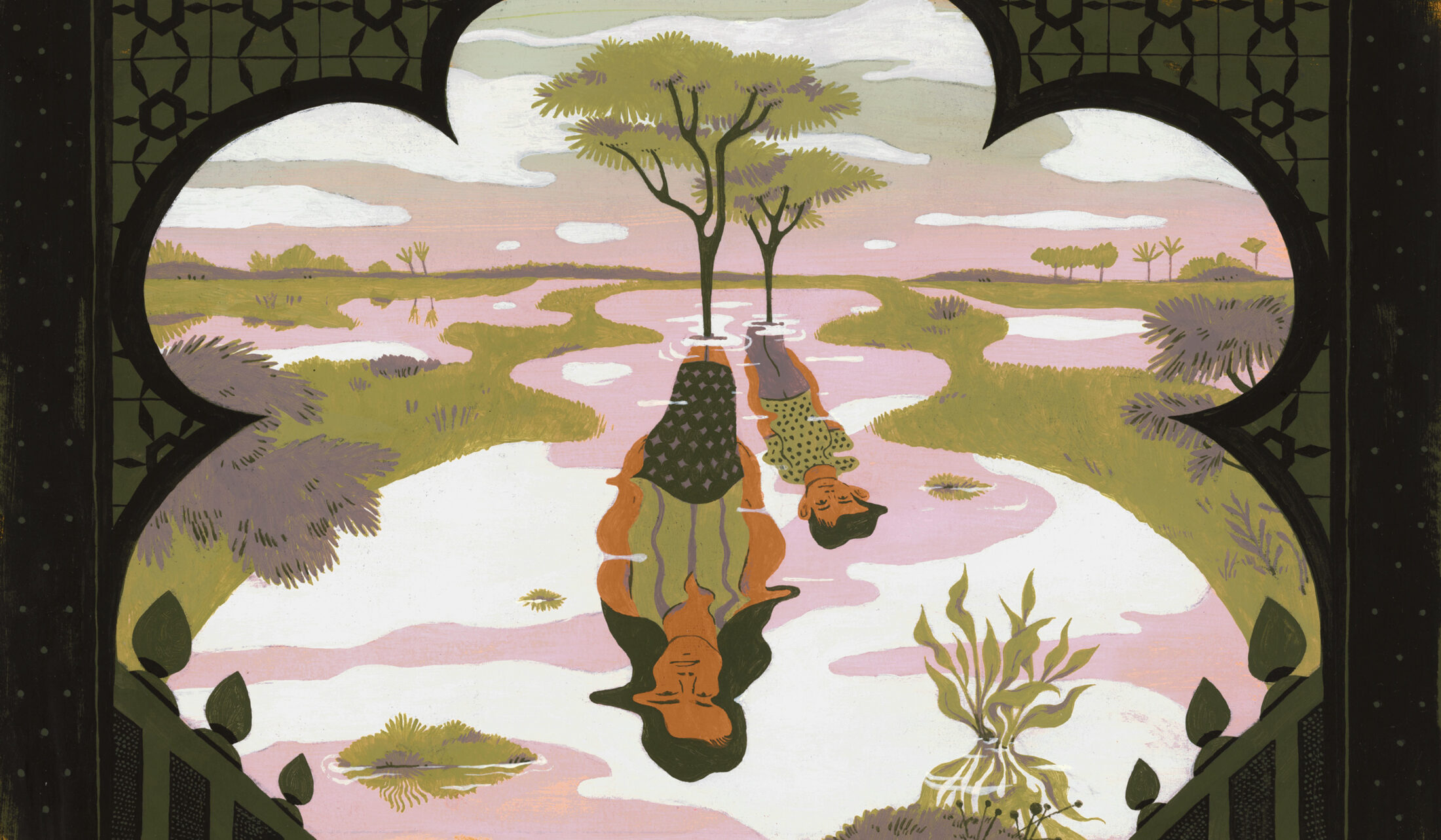

Celia Jacobs is a Portland-born illustrator living and working in Los Angeles. She works in technicolor with a focus on nature, music, and social issues. Her clients include The New York Times, The New Yorker, Google, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Penguin, and more.

At her home in Siliguri, India, Sumana Roy and her nephew reflect on the continuance of all that has vanished from our sight.

My nephew, nine years old, is watering the plants on the terrace with me. His two-year-old sister is playing apprentice—one must learn this too, how to water plants, a skill we take to be as naturally acquired as chewing or walking. She waters every potted plant I water, following me with her small plastic cup—a wholehearted second helping. I try to explain, and then stop. She is too young to identify thirst. Her brother is the opposite. He waters everything except the plants: the cane chairs and table, the tiles on the walls, a clay horse, a rock or two, clotheslines, and, quite often, just himself. He does this when I am looking away or am at a distance from him, watering the bougainvillea plants in the corner.

“Pi,” he tells me, “I just watered this.” He calls me “Pi,” his diminutive for pishi (aunt).

“Why?!” I almost scream.

He’s “watered” the pieces of dead trunks of trees that I’ve brought home over the last two decades of my life in this house. The three he’s watered are remainders from a very old tree in a tea garden where my mother-in-law grew up. The tree would have been much older than she was, and it died in a storm, uprooted and damaged by lightning, a few years after her death. I’d got its remains home. It wasn’t their beauty alone that had made me do this. Nor was this just my habit—people call it “habit”; I know it as affection—bringing abandoned dead trees home. In all the rooms in our house are dead trees I’ve found by the roadside, outside churches and tea estates, inside forests and forgotten gardens. My family has allowed me to give the dead a home in a way that houses and their residents are not conditioned to. I am aware that it is not only while they are alive that plants seem different from animals. Death, in fact, intensifies this difference—the aged dead tree can be admired in a way the corpse of an animal cannot. My nephew has watered three of them.

“If I can water the living plants, why can’t I water the dead trees?” he asks.

I have no answer. Water is useless to the dead … I could say that, but I don’t.

The elements are useless to the dead, as the living are useless to the dead. I do not know of anything that could be useful to the dead. It is to the elements that we return our dead—to fire or to the earth, to burn or to bury—as if acknowledging an intuition that it was from the elements that they were formed. And yet we force water on the dead even after we are made aware that life has departed from their bodies. Hindu rituals, for instance, call for a few drops of water to pass through the lips of the dying, and sometimes a loved one who’s arrived late will try to pour a few drops through the lips of the dead. As a child, I wondered about the water, its passage, where it stopped, how far it could reach, whether beyond the throat into the esophagus, and so on. The gardener’s rituals are not very different—even after we’ve seen all the leaves and branches of a plant dry into lifelessness, we will water them, at least for a few days, just in case they can be resuscitated. It is trust in water, of course, but also in the plant—that a part of it has kept open its lips to allow life in, as if life were a piece of cotton cloth with invisible pores.

The next day, my nephew waters the dead tree trunks again. If living plants need water every day, don’t the dead as well? I am annoyed at the prospect of the tree trunks beginning to rot, but I hide my irritation. The children are staying with me because their mother has COVID. I do not love anyone as much as I have loved them. I say this to myself without any real awareness. The one thing I am aware of is the conflict in my protective instinct—to care for the dead tree trunk as much as I have been doing for the little children. The perimeter of my care extends as much to the dead as it does to the living. And so, after this continues for a couple of days, I tell my nephew, “Do you think green leaves will sprout from a dead tree trunk?”

He shakes his head. His answer is ready: “A living tree will produce green leaves that are living. A dead tree will produce dead trees.”

I stand up straight and look at him from where I am tending fenugreek plants. Tending? No, not really. That I’m plucking to cook for dinner. He’s not looking at me. “Tuku,” I say, calling him by the name that only I use for him.

Tuku and Tuki, my nephew and niece. These are my names for them. The first happened naturally, when my nephew mispronounced the Bangla word for hide-and-seek, tuki, as “tuku.” Seven years later, when his sister was born, I began calling her “Tuki.” Tuku and Tuki, like the poet Shakti Chattopadhyay’s children, Titi and Tatar. Chattopadhyay is one of my favorite poets, and yet I didn’t notice the synchronicity in the names at the time. Tuku-Tuki, like Titi-Tatar. No other writer has written more about plant life in Bangla than Chattopadhyay. A misfit in the social world, Chattopadhyay, in his poems, revealed his desire to live in alignment with the morality of the plant universe. His questions are inevitably unexpected: Are flowers better and greater than leaves? Is the woodcutter a lover of trees? My nephew’s question reminded me of Chattopadhyay. What would he have thought about watering dead plants? No, he didn’t write a poem about that speculation.

My nephew asks about death when we are downstairs. Not once, but a few times. It might be due to the phone conversations he overhears—someone calling my parents or his to tell them about a relative or friend who’s died. “COVID”—we all say that word more than any other throughout the day. How can he not know about death intuitively? Perhaps understanding that life and death are opposites, he rests on “life.” This is without our assistance. He arrives at the difference between them without our nudging as well. To be dead is to be invisible; to be alive, its opposite, he decides. We don’t respond. It’s because we don’t know—we are as ignorant as he is.

We continue to water the plants. Sometimes the children ask about their mother: my niece, two years old and still breastfed, cries for her mother’s body, particularly at night; my nephew asks whether his mother is getting better. I say yes, though she is in another house, inside a room adjoining a terrace. Damage and repair are also invisible, I want to tell the little boy, but I stop myself—I don’t want to make his list of the invisible longer.

I sprinkle water on the soil in a few pots on the balcony. He laughs at me. There are no plants in them. Why am I watering the soil? I tell him about the coriander seeds that I’ve sowed in them. But he’s not convinced. His deductions are immediate—the unborn are like the dead, both invisible; perhaps the unborn are born dead?

All of this is to prove that he was right to water the dead plants. Why shouldn’t he, if I can water the unborn?

One night my niece wakes up at around 1 a.m. There is a power cut, a consequence of the ferocious thunderstorm that’s been beheading trees and blowing tin roofs off houses. Stunned by the darkness, the two-year-old begins screaming: “Ma, Ma, Ma!” My nephew wakes up and volunteers an assessment: if only their mother were visible, his sister wouldn’t cry. As we try to lull her back to sleep, it begins raining again—so hard that the raindrops slap the windowpanes and it feels as if the glass will break. It’s like the sound of schoolchildren walking down the stairs during an earthquake. A cyclone is flooding the southern parts of Bengal. We are in the north. Is it moving towards us? My nephew is not bothered by any of this. Energized by having had some sleep, he says, “Even the rains are watering the darkness, the invisible.” His words are in Bangla, of course: andhakar, the word for “darkness,” sounds scarier and more ancient. As he returns to sleep, shutting his eyes so as to invoke it, the sound of the way he says “andhakar” reverberates inside me—andha means “the blind,” and also the state of blindness.

I soak chickpeas and kidney beans at night. I will cook them the next day. Tuku asks what I am trying to do. When I explain, with the little energy that remains after another exhausting day, he asks whether I am doing the same thing that he was doing on the terrace—reviving the dead with water. I am slightly irritated with him—it’s as if he is stalking my movements to prove his point. He’s a good-natured child, deprived of competitiveness, and has, at least on two occasions, celebrated his failing—once in an exam, another time in a game of sport. He must be onto something in a way only a child can, with untutored curiosity. I tell this to myself and prepare to make the bed for the night.

His sister wakes up again, crying. Tuku is watching Laurel and Hardy on YouTube. We introduced Tuku to them and Chaplin a few days ago, hoping that these actors—so what if they are dead?—would share in some of our babysitting responsibilities. We try to include his sister in the fun—how else can we keep her from crying? The little girl is happy to be united with her brother—sleep had separated them. She laughs when her brother laughs, she stays quiet when he does, she looks at him from time to time, as if waiting for a signal. Then Chaplin falls down a flight of stairs or Hardy gets stuck inside a chimney—I can’t exactly remember now.

Tuku bursts out laughing. Tuki starts crying.

We soon realize that she was scared by the fall, possibly imagining the pain, drawn from her own memory of falling.

Much later, after we are able to put Tuki back to sleep, Tuku says, “The fall was hidden inside him. It was there all the time. Tuki began crying only when the fall became visible.”

It was a strange thing to hear, particularly from a little child. But then, perhaps it was only possible for a child to imagine this—that everything that will happen to us is already inside us, hidden, as a tree is inside a seed. My nephew does not bother to explain any of this to me. It is my adult mind, always trying to reconstruct fallen branches back into a tree. Falling is inside us, just waiting for a moment to become visible—just as death is inside us, waiting for a moment to make life invisible. The death of the flower is the birth of a fruit …

My nephew laughs, my niece cries. Hashi-kanna, laughter and tears, one of the many rhythmical pairs that keep the world in motion, as Rabindranath Tagore’s song, with its beat set to the pattern of breathing, reminds us. The knowledge of Bangla is not necessary; just the sound of the words is enough to get a sense of that rhythm: “mawmo chittey niti nrittey ke je nachey tata thoi thoi tata thoi thoi tata thoi thoi … hashi kanna heera panna…”

Through it all, the tears and the laughter, janmo and mrityu (birth and death), the dance continues—“tata thoi thoi tata thoi thoi tata thoi thoi”—people fall down, people get up, a flower falls, a tendril forms, something becomes visible, something invisible. Tata thhoi thhoi.

Perhaps it was only possible for a child to imagine this—that everything that will happen to us is already inside us, hidden, as a tree is inside a seed.

I am arranging the books that have accumulated throughout the semester from my teaching back into the bookshelves. Tuku joins me there. Everything is a game for him now. Not having had the opportunity to go to school or the playground because of the pandemic, he misses team sport. I am wiping the dust gathered on the covers with a piece of cloth. Out of one or a couple of these books emerges dried leaves and flowers: bel leaves and marigold. My mother would have put them inside my books a long time ago. Used to worship the goddess Saraswati in spring, these leaves and flowers are put inside books, where they live—if this can be called life—almost forever, falling out from time to time but put back gently, with apologies and prayers.

My nephew runs towards the kitchen, as if someone were calling him urgently or as if he’d had a hunger attack. Before I can ask, he’s back with a glass of water. My mind jumps to what he’s about to do. I wrest back the two books from him. No, he cannot water them, I say, even before he has asked to do so.

“Why do you put flowers inside books?” he asks. There is a child’s anger in his voice.

“Not only me. Everyone does,” I say, defensive.

I begin telling him about a book that I’ve been asked to contribute to, how this is a new genre of books that grow into trees once they’ve been read and are planted. I expect him to be excited. He thinks for a moment and says, “Maybe all books are like that. We should plant all your books … even if we don’t plant them, let us water them … they will grow.”

I control my irritation.

But his curiosity is uncontainable. “What will this book grow into?” he asks, holding a volume of the Rabindra Rachanabali (the collected works of Rabindranath Tagore). These twelve volumes of the Bengali poet’s writings and art have become something of a collector’s item in most Bengali homes. Brown, cloth-covered hardbacks with delicate, nearly translucent pages, they are stared at more than they are read.

I decide to read out a poem for him. Since I can’t locate the book in this wilderness into which the residents of the house keep pushing the books they buy, get, read, or keep, I look for the poem online. There it is, like most literature, still undead:

Who are you, reader, reading my poems a hundred years hence?

I cannot send you one single flower from this wealth of the spring, one single streak of gold from yonder clouds.

Open your doors and look abroad.

From your blossoming garden gather fragrant memories of the vanished flowers of a hundred years before.

In the joy of your heart may you feel the living joy that sang one spring morning, sending its glad voice across a hundred years.

From the corner of my eyes, I can spot my nephew’s impatience. He’s waiting for me to stop. Poetry is still a foreign language to him, and I feel disappointed that he’s not listening.

When I come to the last word, he, like a goalkeeper diving to keep the ball out of the goalpost, rushes to get his words in before I can speak again.

“So Rabindranath could see the invisible reader a hundred years ago? He could see you and me reading his poem?”

I feel disappointed in his literal-minded reading, but I am also grateful that he had, at least, paid attention to the words.

“You keep flowers inside books so that Rabindranath can feel that he was sending them to us?”

I struggle to come up with an answer. The poem still here, the flowers “vanished.” Who watered the poem but not the flowers? It was undeniable—Tagore trusted that someone would read him a hundred years hence. The reader was, at that time, an invisible presence to the poet, of course. Was it this that my nephew, with his insistence on nurturing the invisible, meant?

A few hours later, when we were eating lunch, and one of us was giving him a sermon about the importance of eating vegetables, he said, “Why do the vegetables become invisible when they enter us?” And then, drinking from his glass of water, he added, “I’ve watered the plants inside me now.”

I have still not been able to understand the nine-year-old boy’s insistence on the aliveness of the dead and their potential to return to life if only they are cared for—if only they are watered, to be specific. Neither I nor the furniture that my nephew insisted on watering took kindly to the water. It annoyed me, it disturbed the wood—it made both of us lose what we knew as equilibrium. Can one disturb the living in a manner similar to the way we disturb the dead? What are the things that keep the dead alive? In other words, what are the things that keep the dead dead? The water and air and light that were necessary for their life are also necessary—or unnecessary—to keep them dead. To be dead, we know from our secondhand understanding of death, is to stop responding, to stop being the emitter and receiver of a signal.

I have often wondered about my attachment to the dead trees, their aged trunks and branches and roots, that fill my house. How different are they from photos of departed ancestors or departed childhoods that hang from walls in our homes? Why are we reluctant to let go of seeing the dead?

In many Indian languages, the word for “philosophy” and for an unexpected and epiphanous sighting of God is the same: darshan. The architecture of ancient Hindu temple towns, such as Konark or Mahabalipuram, reiterates this. We see this as much in the statues and sculptures as in the rituals of worship: gods are to be caught in the middle of their everyday activities—bathing or being bathed, eating or being fed, listening to songs being sung for them, watching dances performed for their entertainment, listening to prayers being recited for them so they can remain educated—and, often, even when they are sleeping. Whatever their posture might be—sleeping, standing, sitting, or reclining—just a sighting of the gods in the middle of their daily activities is enough for the believer, for the devotee, for the person on pilgrimage. The idea of philosophy being a similar kind of darshan, or seeing, is similar to this—like the devotee’s unexpected sighting of God, the darshanik, or philosopher, is allowed a moment’s insight into something that they had been seeking. My nephew’s insistence that the difference between the living and the dead was simply a matter of visibility, of life being more visible than death, and the living being more visible than the dead, led me to this idea of darshan. Darshan—this epiphanous sighting, both to see and be seen—is available only to the living. That is perhaps why in many cultures, like mine, for instance, the eyes of the dead are shut and a holy basil leaf is placed on the forehead of the departed.

My nephew’s inability to differentiate between the unborn and the dead is part of an inheritance of thought that is hard to escape. Think of D. H. Lawrence putting them together, for instance: “Whatever the unborn and the dead may know, they cannot know the beauty, the marvel of being alive in the flesh.” The chiasmus-like structure of our spiritual inheritance—whether it is the dust-to-dust of one religious culture or the kal-aaj-kal (“past-present-future” in some Indian languages, where the word for “past” and “future” is the same) of another—might be responsible for conditioning our imagination to think of the afterlife as generically similar to the before-life. The little boy’s insistence on “darshan”—without using the word, of course—as a mark of the living, and the invisible as being the province of the dead, might also have come from the literature and cinema that he had been exposed to. While the past and the future might be similar and the unborn might be similar to the dead, we like to imagine God as being responsible for our having come to life and ghosts as the by-products of our death. What I mean to say is that we do not think of ghosts as being responsible for our life, and we do not die to become God. Carcasses, of humans and other animals, are removed from our range of vision—we do not want to meet the dead. It was perhaps this that was niggling my nephew—that we allowed dead plant life space in a way we do not allow animals.

Trees travel a little more in their afterlife than they do when alive. There is another world, but it is in this one.1

- Often attributed to Paul Éluard.