Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

As the existence of the famed ivory-billed woodpecker is increasingly left to the realm of myth, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder explores the widespread disappearance of birds in the narratives of apocalyptic prophecy that run through our collective consciousness.

For in seven days I will send rain on the earth for forty days and forty nights; and every living thing that I have made I will blot out from the face of the ground.

—Genesis, 7:4

No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves.

—Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

I.

James Tanner was a graduate student at Cornell University when he was offered a three-year Audubon Research Fellowship to study the famed ivory-billed woodpecker in its native habitat. The fellowship would mean thousands of miles on the road, hundreds more trudging on foot through swamps filled with poisonous snakes, mosquitos, and wolves, and little opportunity to settle down. It also meant the chance to save a bird that, until several years ago, had been presumed extinct. Jim didn’t hesitate in saying yes.

He had been an avid birder since he was a teenager. He taught himself to mimic bird calls; he learned to sit still for hours with his back against the trunk of a tree; he trained a wounded golden eagle to hunt from his arm.

Long before he arrived at Cornell University, the ivory-billed woodpecker, Campephilus principalis, had been disappearing across the United States. Increasingly rare sightings of this vanishing species had pushed its existence into the realm of myth. The ivorybill was the largest woodpecker in North America, measuring up to twenty-one inches in length with a thirty-inch wingspan. Its bill was made of bone covered in keratin and was rooted deep in the bird’s skull, allowing it to absorb the shock of drilling into trees and giving it leverage to strip away huge pieces of bark to get at the grubs that made up its diet. For centuries, people had been particularly drawn to the ivorybill’s beauty: the regal crested head, deep red on the males, velvet black on females. The rest of the bird’s plumage was composed of layered sheens of blue-black feathers interspersed with striking patterns of white on the wings and neck.

Jim had spent the previous summer with Dr. Arthur Allen and his team from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology on an expedition to the Singer Tract, land owned by Singer Manufacturing Company—previously known as the Tensas Swamp—in Louisiana’s Mississippi River Delta. Here, the team had observed and recorded several nesting pairs of these extraordinary woodpeckers, and Jim had at last witnessed the graceful swooping flight of the bird firsthand. He had heard its distinctive nasal kent call and its characteristic double-tap on the trunks of trees. He had left Louisiana reluctantly when the expedition ended, eager for a way to return.

And now he had one. Jim’s three-year contract with the Audubon Society required him to visit every site in the United States with habitat suitable for ivorybills: the great upland pine forests and river-bottom swamps that ran from Texas to Mississippi to North Carolina. His primary mission was to learn all he could about the ecology of the species and to return home with enough data to convince both private landowners and Congress to take steps in preserving the bird’s habitat. Jim was to research and travel to every forest where locals had long reported seeing the “Pearly Bill,” the “Log-god,” the “King Woodchuck”—a great woodpecker, unlike any other bird, they would say. The ivorybill also frequently went by the moniker “Lord God Bird,” for when it swooped into view, people were known to shout, “Lord God, what a bird!”

But ivorybills were nowhere to be found along the Altamaha River in Georgia, nor in Florida’s Everglades, nor along the Suwannee River.

In his third month on the road, Jim returned at last to the Tensas River and the Singer Tract, where he observed what he believed to be seven nesting pairs of ivory-billed woodpeckers over the course of several months within the Tract’s 80,000 acres.

The following spring, he could only find two pairs of ivorybills, three lone adults, and three young birds—for a total of ten. He found just one nest that had hatched a surviving chick.

In the final year of his three-year term, Jim noted only four ivorybills within the Singer Tract, which he believed to be the last site in North America where the birds existed. It was no coincidence that this was one of the few virgin forests left intact in the American South.

“The Singer Tract was the one forest that looked and felt and smelled and sounded as it must have thousands of years before,” writes Phillip Hoose, author of The Race to Save the Lord God Bird. “There was a good chance that every single species that had ever lived in this forest was still there except for the Carolina Parakeet and the Passenger Pigeon—both extinct. Everything else—from Ivory-bills, panthers, and wolves to grubs, mites, and frogs—was still there.”

At the conclusion of his fellowship, Jim delivered a grave and urgent report to the National Audubon Society. He understood the rapid decline of the ivorybill population to be a symptom of starvation, which had reduced their ability to produce viable offspring. The bird, he wrote, relies on the existence of huge swaths of forest, up to six square miles per bird, to have enough of their primary source of food: beetle larvae, which is found especially in sweet gum and Nuttall oak trees. In order for there to be enough larvae, there must be an ongoing cycle of old trees dying a natural death.

But sweet gum and Nuttall oak were also the most desirable trees for the logging industry. Already, the lumber companies had bought and cleared thousands of acres of the South’s vast, primeval forests. Singer’s owner had recently sold six thousand acres to the Tendall Lumber Company and was receiving generous offers for the rest. The Chicago Mill Company was already logging on the western side of the Tensas River.

The ivorybill was running out of time. The year was 1939.

In short order, WWII would create the next lumber boom, Jim Tanner would be drafted into the army, and efforts to conserve even a small part of the Singer Tract would fall through. The ancient trees proved too valuable to be protected.

In 1944, Don Eckelberry, a wildlife artist, spotted an ivorybill in one of the remaining pockets of forest left standing in the Singer Tract: a lone female, calling through the trees.

His was the last universally accepted sighting of the ivory-billed woodpecker in the United States.

II.

In 1961, DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) was registered with the USDA for use on 334 different crops in the United States. A chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticide, DDT was inexpensive, widely available, and enormously effective in its ability to both control insect pests of all varieties and to keep them under control for extended periods of time due to its persistence in the environment. Farmers in the United States sought out DDT, BHC, aldrin, dieldrin, endrin, 2,4-D, and toxaphene with enthusiasm. All of these organic compounds were promoted by both corporations and the federal government as safe for human use.

That same year, the United States was embroiled in the Cold War. The looming specter of communism extended all the way down to the insects that threatened the viability of the American food supply. As Christopher J. Bosso writes in Pesticides and Politics: “The pest threat … was seen in almost apocalyptic terms, pest control seen as a ‘never ending struggle between man and nature.’ Worse, a threat to agriculture was a threat to national security, and pesticides increasingly were defined as yet more weapons in the cold war.”

In the largely ideological battle waged against the Soviet Union, the chemists who created these pesticides—alongside the scientists who were producing weapons and technology—were seen by the public both as a key to winning the war and as ushering in America’s modern future. Rachel Carson’s biographer, Linda Lear, writes: “The public endowed chemists, at work in their starched white coats in remote laboratories, with almost divine wisdom. The results of their labors were gilded with the presumption of beneficence. In postwar America, science was god, and science was male.” The belief in man’s ability to wield control over natural forces in order to serve the common good, in order to progress rapidly into a new glorified age, was a strong and positive current running through the collective consciousness.

Something else was happening in the early 1960s: birds were fast disappearing across America. Few were paying attention to this occurrence.

Such was the context when Rachel Carson—a marine biologist and author who had long been raising the alarm about the use of agricultural pesticides—published Silent Spring in 1962. Carson drew on the public’s fear of the effects of nuclear fallout and radiation to highlight the similarly invisible threats that chemical pesticides posed to health and well-being. Her work immediately came up against the wall of a powerful industry that relied on the production, sale, and widespread use of chemicals, and up against the mindset of the public, which had long been assured that these chemicals were safe. For years prior, chemical industries and governmental institutions alike had worked diligently to downplay concerns that widespread and indiscriminate use of pesticides could have any detrimental effects on the human body or could harm anything but the bodies of the insects they were intended to kill.

But Carson’s eloquent, patient prose was detailed and deeply accessible. Silent Spring’s third chapter, “Elixirs of Death,” confronts the chemical industry head-on. Companies that produced pesticides like DDT had classed them as “organic compounds.” Indeed, Carson writes, DDT—a chlorinated hydrocarbon—is built of carbon atoms, “the indispensable building blocks of the living world.” But carbon has an “almost infinite capacity” for linking itself with other atoms and molecules. Thus, “although linked with the basic chemistry of all life, [carbon atoms] lend themselves to the modifications which make them agents of death.”

She goes on to lay out—in devastating case after devastating case—the disastrous environmental consequences of these insecticides on bird populations, human populations, and entire ecosystems. Throughout the book, Carson takes her time with the Earth’s biomes—seas, soils, forests, grasslands, rivers—and the universal introduction of harmful chemicals within each of them, traceable in everything from birds’ eggs to the breast milk of every human mother on the planet. Carson writes of the environment as an interwoven ecosystem, in which humans are participants alongside the coho salmon and the mule deer. She documents outbreaks of leukemia among children, the sudden death of sixty-five thousand red-winged blackbirds and starlings, the destruction of the western sagebrush lands, which were chemically treated in an effort to turn the land to grass suitable for grazing cattle:

If ever an enterprise needed to be illuminated with a sense of the history and meaning of the landscape, it is this. For here the natural landscape is eloquent of the interplay of forces that have created it. It is spread before us like the pages of an open book in which we can read why the land is what it is, and why we should preserve its integrity. But the pages lie unread.

The sage was destroyed, and with it the populations of grouse and antelope. “The living world,” she writes, “was shattered.”

Silent Spring succeeded in raising the alarm. Despite the power of the chemical industry, the public response was shock and outrage.

“Like the constant dripping of water that in turn wears away the hardest stone, this birth-to-death contact with dangerous chemicals may in the end prove disastrous,” Carson warned, and her stark chapters painted a clear and disturbing picture of how that disaster was unfolding. The book marked a turning point in ecological awareness within the United States. Carson’s foreboding book led to the launch of governmental investigations; it armed communities with knowledge that gave rise to grassroots environmental movements across the United States; it ushered in regulations and conservation efforts that not only banned myriad pesticides, including DDT, but led to the restoration of populations of osprey, bald eagles, and many other bird species. It ignited much of the environmental movement that we know today.

Carson did not live to see many of these changes implemented. She died of breast cancer eighteen months after the book’s publication.

Perhaps the most enduring warning from Silent Spring comes from its title: Carson’s prediction that, if we do not change our course, we are fast approaching a world without the songs of birds.

Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song. This sudden silencing of the song of birds, this obliteration of the color and beauty and interest they lend to our world have come about swiftly, insidiously, and unnoticed by those whose communities are as yet unaffected.

But surely the most haunting warning from Silent Spring—the darker prophecy that runs like a live wire beneath Carson’s explanation of the poisoning of ecosystems and the mass deaths of creatures—is of something much more sinister. “The ‘control of nature,’” she writes, “is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man.” We are poisoning ecosystems because we remain firmly in the grips of this age of thinking, she tells us. We destroy what we do not understand, what we do not love. We are killing the birds and building a silent world because we seek to control what is not ours. And, when we do, we are slowly, meticulously, and surely, destroying ourselves.

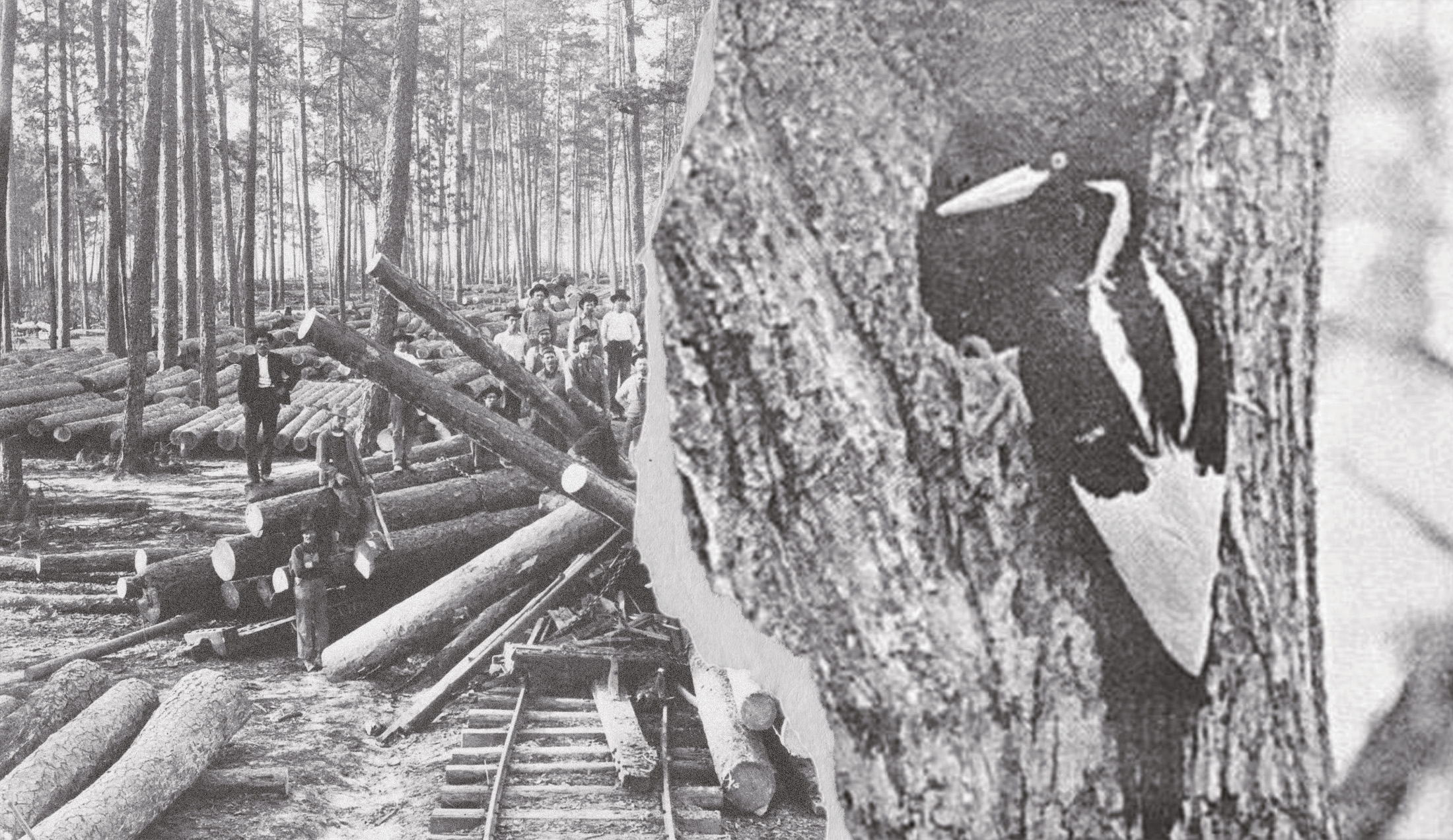

Photo by Arthur A. Allen

III.

Let us return, then, to the fate of the ivory-billed woodpecker.

The great forests of the American South were once filled with ancient oak, sweet gum, and cypress trees with trunks as big around as the arm spans of five men. The range of the ivorybill once extended from the southern tip of Florida, north to Illinois and Indiana, west to Texas, through forests that were home to panthers, wolves, and the passenger pigeon.

But the fate of Southern forests began to change rapidly in the late 1800s. In 1877, after the Civil War, Southern states regained the ability to control their lands, which included the ability to sell them. Most of the northern forests had already been cleared, and the North was running low on timber. And so it was, the processes of supply and demand invaded swaths of ancient trees; millions of acres of Southern forests were felled.

Northern and British lumber companies formed to meet the demand. The railroads came next. In 1880 alone, 180 new railroad companies were formed east of the Mississippi. With the advent of the double-bit saw, centuries-old trees could be felled by two men in the course of an hour.

By 1885, ivorybills had vanished from the state of North Carolina. By 1890, they were gone from Mississippi with dwindling populations in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Alabama.

As ivorybills became increasingly rare, they became increasingly valuable for scientists and collectors. In fact, scientists and collectors were often one and the same. “In those days, before cameras, an assortment of field guides, and binoculars, the most reliable way to study birds was to kill them and examine them closely,” writes Phillip Hoose. Arthur Wayne, a lover of birds and a professional collector who penned the first field guide to the birds of South Carolina, killed and collected over forty ivorybills between 1892 and 1894 alone. His contemporary William Brewster, a renowned and respected bird expert, had forty thousand bird skins of all different species in his sprawling collection by the time of his death.

At the time, the idea that a singular species could play a vital role in a complex ecosystem was not well understood. Until Jim Tanner’s study decades later, it would not be clear that the ivorybill was critical to the regeneration of old-growth forests—it expedited the rate of decomposition of a dead or dying tree by drilling large holes that enabled other insects to enter, thus causing the tree to weaken and fall more quickly. When it did, it left a space in the canopy which allowed sunlight to reach the saplings on the forest floor. Few imagined that humans could be responsible for the destruction of a species, and it was highly impractical for anyone to conduct a nationwide survey to observe how an individual species was faring. And either way, the birds’ increasing rarity meant there was opportunity to make a healthy profit.

The Tensas Swamp became the Singer Tract in 1913, purchased by Singer as the United States was quickly running out of oak trees. Singer sewing machines, which were loved for the way they folded down into elegant cabinets, were made best when made from oak, and so Douglas Alexander, president of the company, bought the Tensas Swamp for nineteen dollars an acre, cushioning his company with thousands of acres of insurance were they to run low on oaks at their other sites. He promptly declared it a “refuge,” meaning simply that trees couldn’t be cut by anyone but him. To regulate illegal hunting, felling, and trespassing, Alexander partnered with Louisiana’s Fish and Game Department to manage the lands. What came to be known as the Singer Tract remained largely untouched for two decades.

By the time Jim Tanner was a student at Cornell in the mid- to late-1930s, ornithologists believed the ivorybill had likely been extinct since the last confirmed sighting in 1924 by Dr. Arthur Allen (known to everyone as Doc Allen). But in 1932, a lawyer from Louisiana shot and killed an ivorybill along the Tensas River in Louisiana. Professional and amateur birders arrived on the scene and discovered several more ivorybills in the area. So it was that Doc Allen and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology made their expedition to the Singer Tract, with Jim Tanner in tow.

In the 1930s and ’40s, ornithologists were becoming increasingly interested in the ecologies of the species they were studying. It had been common practice to kill the birds in order to study them more closely. But as the toll of these collections was becoming more apparent, scientists were revising their methods, choosing to study living birds interacting with their natural habitats rather than dead specimens examined later at home or in a lab. The Cornell expedition was one in which, as Doc Allen said, they would “leave guns at home and would ‘shoot’ the birds with cameras, microphones, and binoculars.”

To say that the available recording devices available at the time were cumbersome would be a drastic understatement. The team arrived in the Mississippi River Delta with 1,500 pounds of equipment and set about the logistical puzzle of getting it into the middle of a vast swampland.

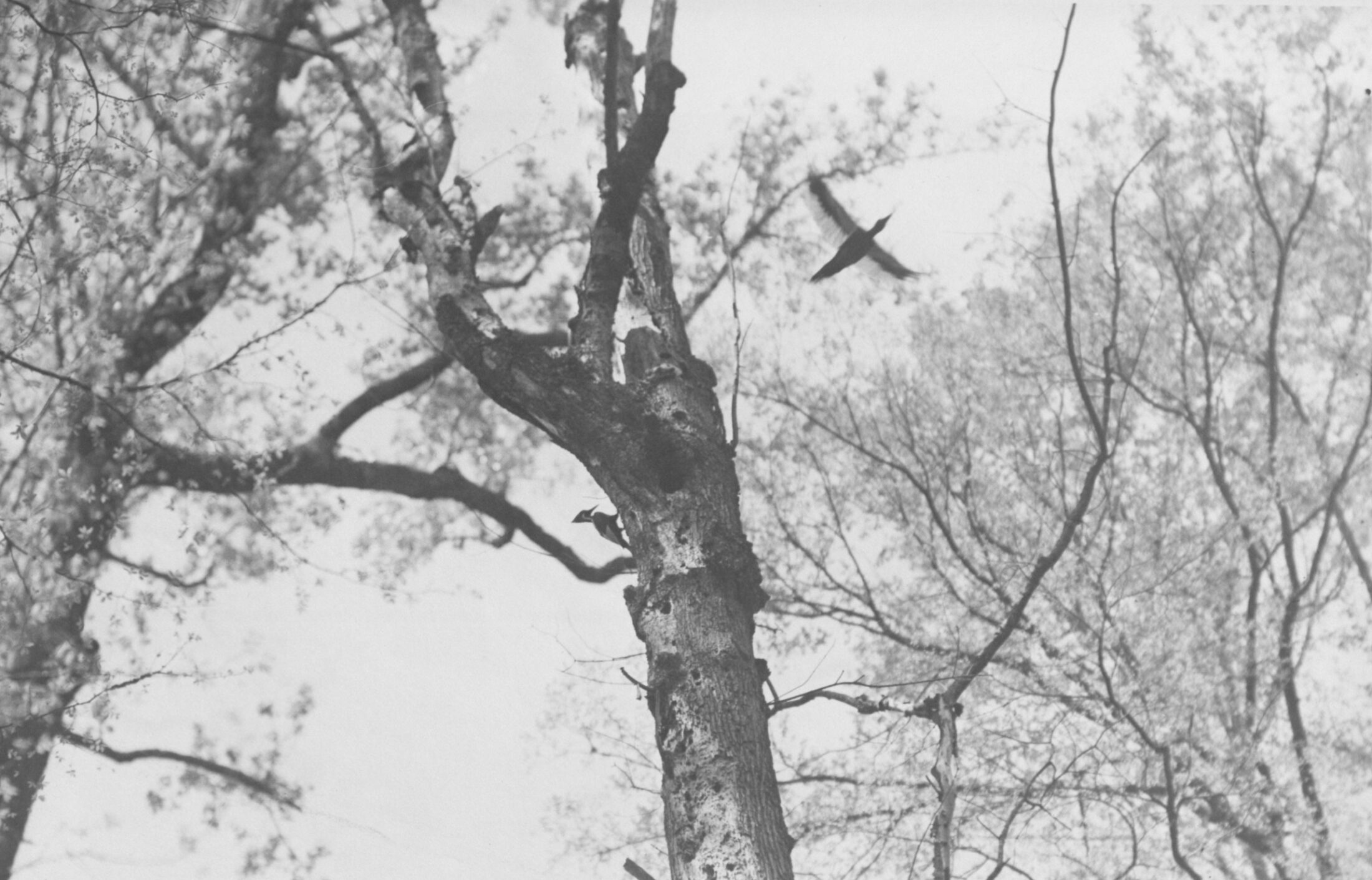

With the help of Singer warden J. J. Kuhn, the team hauled their equipment into the far reaches of the swamp by mule and wagon to the site where Kuhn, too, had recently spotted a pair of the great woodpeckers. Within several days, the team located the pair as they were tending to their nest. They set up camp. Over the course of five days, they recorded the first audio and video footage of adult ivory-billed woodpeckers. The birds can be seen arriving at and then leaving the tree, grasping the trunk with their four scaled toes, jerking their heads side to side, and taking flight, their wings forming an elegant line beneath the tangled canopy.

It remains the only definitive footage of the bird in existence.

After Jim’s subsequent three-year fellowship, the Audubon Society had a chance to conserve four thousand acres of the Singer Tract, land that had recently come into the ownership of the Chicago Mill Company. The company had planned to log the forest, but they were facing a labor shortage: it was 1941, and so many men were being drafted into the army to fight in the Second World War that they had no one to fell the trees. They became willing to sell the land instead. But just as they were about to reach a final agreement with the Audubon Society, German prisoners of war arrived in the United States to fill the labor gap. Between 1943 and 1946, 375,000 Germans were put to work across forty-four states. Chicago Mill suddenly had more than enough free labor.

Thus, the ivory-billed woodpecker was felled with its trees. The bird was once again declared extinct.

Jim Tanner returned to the Singer Tract one last time in 1986, several years before his death. The land had at last been preserved and was now known as the Tensas National Wildlife Refuge. It was unrecognizable to him. The great bottomland forest had been flattened. His beloved birds had long been dead.

We are killing the birds and building a silent world because we seek to control what is not ours.

Since 1945, scattered claims of ivorybill sightings have been reported across the South, cropping up every few years. Once enough of these claims accumulated, they began to fuel the belief among some that the ivorybill, against all odds, was still alive in the South’s remnant and recovering forests. But no one has been able to capture a convincing photograph, and the claims have almost always been dismissed by the scientific community as fabrications or misidentifications.

The sightings, however, have been enough to keep the memory of the bird alive, and the Lord God Bird has taken on an air of legend and myth. Each sighting strengthened its aura of ghostly mystery, like a being resurrected from the dead, and people began to go on quests to find it. Thus the ivorybill came to have another name—the Grail Bird.

In 1999, a turkey hunter claimed he saw an ivorybill in Louisiana’s Pearl River Wildlife Management Area near New Orleans. The report was credible enough to spark a hunt. Three years later, an international team of scientists organized an intensive search of the area. They did not find the bird.

Tim Gallagher, a lifelong birder and editor in chief of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s publication Living Bird, had been fascinated with the ivorybill for nearly thirty years at the time of the Pearl River sighting. Following that account, Tim began researching clues on where else the bird might still be found. He eventually traveled to the South himself to interview locals who’d seen (or had claimed to have seen) an ivorybill, including Nancy Tanner, Jim Tanner’s wife.

At last, in February 2004, Tim and his friend Bobby—part of a team from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology who had formed a search party within the Big Woods of Arkansas—were in a canoe together when a bird flew past, sounded a nasal kent call, and alighted on the trunk of a tree a few yards ahead of them. Their unanimous cry of “ivorybill!” startled the bird, causing it to flee deeper into the trees. Unable to track the bird further into the swamp, Tim and Bobby each drew a picture of it before discussing with each other what they each had seen. Both drawings showed the unmistakable markings of an ivory-billed woodpecker: white feathers on the trailing edge of the wing.

The Cornell team waited several days before sharing the sighting with anyone, knowing that claiming such a sighting could damage their reputation. They had to be sure. At last, convinced that he had indeed seen what he thought he had seen, Tim took his findings to John Fitzpatrick, the director of the Lab of Ornithology, who, based on Tim’s account, agreed that this bird had likely been an ivorybill.

Following a number of sightings over the course of the following months, including blurred video footage of an ivorybill filmed from a canoe in Arkansas’s Bayou DeView, Cornell Lab of Ornithology and The Nature Conservancy jointly announced the rediscovery of the ivory-billed woodpecker in April 2005. The news spread instantly. The town of Brinkley, Arkansas, near the Big Woods, experienced a boom of tourism. The local salon began advertising the “ivory-bill haircut,” restaurants sold “ivory-bill cheeseburgers.” Once again, amateur and professional birders from across the country flocked to the area and set out into the woods, drawn into the quest to spot the resurrected bird. Though many ornithologists, including David Sibley, were unwilling to acknowledge that the bird was definitively rediscovered, there was enough of a consensus to prompt action. In a multimillion-dollar effort, The Nature Conservancy purchased and permanently conserved thousands of acres across Arkansas, in and surrounding the Big Woods.

As Tim Gallagher wrote in his subsequent book, The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker:

What happened to the vast bottomland forests of the South during the past 150 years is one of the greatest environmental tragedies in the history of the United States, and few people know about it. These are still one of our most neglected and abused habitats. Nothing symbolizes what we have lost more than the ivory-billed woodpecker. Just to think that this bird has made it into the twenty-first century gives me chills. It’s as though a funeral shroud has been pulled back, giving us a brief glimpse of a living bird, rising like Lazarus from the grave.

Fifteen years later, the blurred video footage from the Bayou DeView remains the most recent widely accepted footage of the ivorybill. There have been no photographs, no audio recordings. Subsequent sightings have once again drawn skepticism.

The American Bird Conservancy’s website lists the ivory-billed woodpecker’s “status” as critically endangered, and the “trend” of its population as probably extinct.

The ivorybill has come to occupy a liminal space between extinction and existence.

Many have declared the search over and further assert that the search has been over for eighty years. But many are still out looking; navigating the Big Woods, the Tensas National Wildlife Refuge, the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area; wading through swamps, pushing canoes, camping beneath oak trees, swatting mosquitoes; watching the trees to catch a glimpse of this Lazarus, listening for the double-knock of the Lord God Bird.

IV.

A 2018 Pew Research study found that, on average, 67 percent of the world’s population believes that global climate change is a major threat (compared to 56 percent in 2013). The same study reported that 59 percent of Americans view climate change as a serious concern, a relatively low percentage in comparison with other industrialized nations: 83 percent in France, 75 percent in Japan.

Indeed, the concerning evidence is mounting. In 2019, a report entitled “The Decline of the North American Avifauna” was published in Science magazine. The report documented a drastic decrease in the North American bird population, a loss of three billion individuals since 1970, with habitat destruction and fragmentation reported as one primary factor, pesticide use as another.

In her introduction to the fortieth anniversary edition of Silent Spring, biographer Linda Lear writes: “In spite of decades of environmental protest and awareness, and in spite of Rachel Carson’s apocalyptic call alerting Americans to the problem of toxic chemicals, reduction of the use of pesticides has been one of the major policy failures of the environmental era. Global contamination is a fact of modern life.” One billion pounds of pesticides are used annually in the United States; pesticides that have been banned in the European Union due to environmental and health concerns account for a full quarter of this use.

While pesticides such as DDT were banned in the years after Silent Spring was published, chemical spraying continues to wreak havoc on bird populations. Pesticides called neonicotinoids, used to treat seeds in agricultural areas, were the subject of another Science article entitled “A neonicotinoid insecticide reduces fueling and delays migration in songbirds.” In it, researchers found that exposure to this insecticide delays and limits the ability of songbirds to put on weight. “Such delays can lead to reduced migration survival and decreased reproductive success and therefore have the potential to impose population-level impacts.”

Photo by James T. Tanner1

Photo by James T. Tanner2

In grasslands, wetlands, boreal forests, eastern forests, coastal areas—human activity has silenced nearly three billion birds in North America alone.

As to the damage being done to the rest of the planet—its plants, creatures (including human beings), and ecosystems—robust evidence has been delivered in reports from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), annual statements from the World Meteorological Organization, and World Health Organization fact sheets. The website of the Union of Concerned Scientists includes the following statement:

Scientists have studied global warming for more than 100 years. Thousands of experts have tested hypotheses, gathered evidence, constructed models, debated results, and reviewed one another’s work. Thousands of papers are written every year, produced from nearly every leading university and research institution on Earth—from Harvard to NASA and the US Department of Defense.

The consensus couldn’t be clearer. Climate change is happening. It’s caused primarily by the burning of oil, gas, and coal. If we do nothing, the world will become significantly less habitable.

We’ve lost precious time, but if we act now—decisively and dramatically—we still have a chance at avoiding climate change’s most catastrophic impacts.

And yet, despite the fact that the devastating effect of human impact on the environment has become widely accepted as truth, despite the fact that the birds are truly falling silent, despite the fact that we have seemingly endless omens pointing decisively toward disaster—and that we believe these to be signs of an impending collapse—we have not managed to reverse the tide.

It begs this sort of question: Why are we inclined to strongly resist the disappearance of the ivory-billed woodpecker, while the disappearance of three billion other individual birds has largely escaped our notice and failed to capture our imagination?

V.

Eschatology is defined as “a branch of theology concerned with the final events in the history of the world or of humankind”: in other words, apocalypse.

For thousands of years, apocalyptic prophecies were firmly grounded in religious theology and were often “a product of both hope and despair; hope in the eternal power of God, and despair over the present evil conditions of the world,” notes Dr. L. Michael White in his article “Apocalyptic Literature in Judaism and Early Christianity.” Such prophecies can be found throughout the Abrahamic traditions and texts, and it was, in part, through the widespread influence of these traditions in Western cultures that “a future-looking sense of history was born,” writes White. Abrahamic traditions are largely credited for creating a culture in which people are inclined towards—and in many ways resigned to—the idea that we are moving inevitably into a future that will be drastically different from the present.

Take the Book of Daniel, a text located in the Jewish Ketuvim and found among the prophets in the Christian Old Testament. In it, Daniel receives a series of apocalyptic visions, interpreted for him by an angel. He witnesses the fall of the Babylonian Empire, subsequent Persian rule, the era of Alexander the Great, and the attacks against Jerusalem that would be carried out by the ruler Anthiochus. This future unfolds for him through a series of repeated, wrathful endings and punishments that ultimately result in redemption and a new beginning for his people:

There shall be a time of anguish, such as has never occurred since nations first came into existence. But at that time your people shall be delivered, everyone who is found written in the book. Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt. Those who are wise shall shine like the brightness of the sky, and those who lead many to righteousness, like the stars forever and ever. (Daniel 12:1–3, OAB)

Widely believed to have been written in 167 BCE, just before the Maccabean Revolt—the Jewish rebellion against the Seleucid Empire—the Book of Daniel was a means by which a community facing religious persecution and approaching a time of great turmoil was both prepared for a time of violence and destruction and encouraged to take heart in a promised outcome of freedom and redemption.

Revelation, the final book of the New Testament, is arguably the most iconic eschatological text in the Bible and, arguably, the most iconic apocalyptic text in our mainstream collective consciousness in the United States. Likely written during the reign of the emperor Domitian between 81 and 96 CE, the book is broken into a prologue, epilogue, and a series of visions, and is filled throughout with cryptic layers of imagery and symbolism depicting the fall of Babylon—a symbol of Rome—and the subsequent arrival of the kingdom of God.

In his commentary on Revelation in The New Oxford Annotated Bible, scholar Jean-Pierre Ruiz writes that the text is “a work of extremes, ranging from soaring heights of hymnody inspired by Hebrew psalms and canticles to the gruesome language of plagues, warfare, and bloodshed. It uses the dualistic language characteristic of the apocalyptic genre to paint vivid portraits of the opposing sides in the eschatological conflict that will culminate in the victory of God and the final defeat of all evil.” The reader is carried through the battle of Armageddon, the four horsemen of the apocalypse, the seven angels who blow trumpets that cause the final seven plagues: burning mountains fall into the sea; hail and fire fall from the skies.

Until, at last, a new heaven and a new earth emerge:

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

….

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.”

(Rev. 21:3–4, OAB)

Revelation, unique in its scope and symbolism, speaks to the diversity and evolution of the apocalyptic genre across a span of years dating from roughly 200 BCE to 100 CE. Nonetheless, it shares common elements with other eschatologies found in the Jewish and Christian canons—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos, Joel, Zechariah—and in non-canonical Jewish and Christian texts as well—The Book of Enoch, The Fourth Book of Ezra, The Apocalypse of Abraham, The Apocalypse of Peter.

Each of these stories centers, in some form, on an approaching time of divine judgment enmeshed with a violent ending that results, ultimately, in a new beginning for God’s people. The stories thus both predict utter destruction and encourage believers to endure, to wait for the triumph of good that will follow. Pain and suffering will abound, but a righteous people will always emerge victorious.

Biblical apocalyptic narratives thus foretell our doom and guarantee our redemption.

We are primed to receive end-time stories.

The secondary definition of eschatology is “a belief concerning death, the end of the world, or the ultimate destiny of humankind.” This definition allows for the extension of apocalyptic narratives into the realm of science, paving the way for a “scientific eschatology” of sorts. And what is a scientific prophecy of apocalypse? Where do we find such stories that foretell death and the ends of worlds?

Today’s mainstream apocalyptic prophets are—by and large—secular scientists and environmentalists: those who are witnessing and interpreting the signs of an approaching (and increasingly inevitable) ecological collapse, or a cascade of ongoing ecological collapses, and issuing forth warnings of the dire consequences of our actions.

Such stories, of course, abound. The IPCC’s 2018 special report “Global Warming of 1.5°C,” based on analysis of six thousand scientific reports, predicts increases in droughts, famine, wildfire, rates of species extinction, destruction of coral reefs, and much, much more. All of these occurrences are already upon us; to what degree they will worsen depends on our ability to act immediately and with far-reaching changes. The editors chose one quote to place on the cover of the report, from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: “Pour ce qui est de l’avenir, il ne s’agit pas de le prévoir, mais de le rendre possible.” (“As far as the future is concerned, it is not a question of foreseeing it, but of making it possible.”) Though this epigraph rings with a note of hope and possibility, the question lurking behind it is whether or not there will be a future at all.

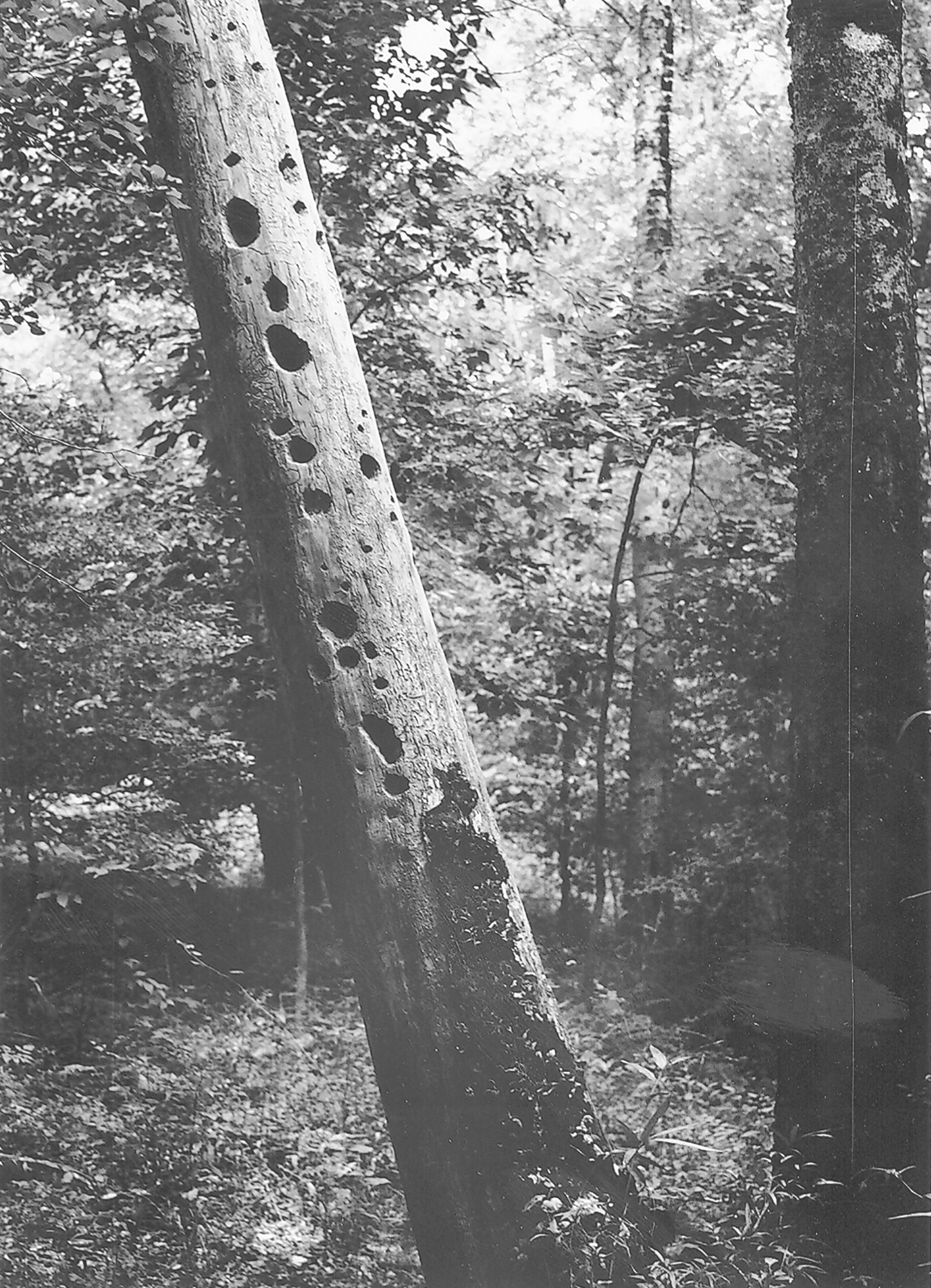

Photo by James T. Tanner3

Scientists and environmentalists would likely cringe at the word “apocalypse.” They would not be keen to see themselves as prophets. The fact that climate change is often referred to in this way has been a source of dismay and controversy, both within and beyond the scientific community.

And yet—despite the data and method at play, despite the careful and specific language, despite the subtleties and complexities of studies and reports—scientific predictions of ecological collapse enter our collective consciousness, where they are often cast in an eschatological mold. We are primed to receive end-time stories. It seems we cannot help but refer to these warnings as “apocalyptic.” Last year, Jonathan Franzen published a controversial article in The New Yorker entitled “What if We Stopped Pretending?” with the tagline: “The climate apocalypse is coming. To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.” Greta Thunberg wrote in her book, No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference: “Around 2030 we will be in a position to set off an irreversible chain reaction beyond human control that will lead to the end of our civilization as we know it.” There is a whole emerging genre of apocalyptic fiction in which humanity has entered a dystopian future following climate catastrophe.

Where religious eschatologies foretell an unalterable future, the science of climate catastrophe trades inevitability for prescriptions for averting disaster: drastically curtail—and then cease—carbon emissions; stop slashing and burning the rainforest; turn to renewable energy. We are, in other words, offered a way out. These endings are not written in stone.

But while this offers the possibility of changing our future, rewriting our ending, it also makes the picture of what is to come messier, less clear. The story begins to lose its arc. We are given no promise of divine intervention and are left with the impossibly huge task of rescuing ourselves. Unlike the victorious endings of the Book of Daniel and Revelation, the eschatologies that are grounded in science hold little redemption for humanity. There is no heroic return to a new world that has been washed of its sins, where the topsoil gets to be put back, where species become un-extinct. These data-based forecasts are more complex. And they predict a future in which we are not so easily forgiven.

And this, perhaps, explains part of the story of the ivory-billed woodpecker. For this is a species that exists somewhere between a religious and scientific eschatology: between complete annihilation and heroic survival, between reality and myth, between a mark of our failure and hope for our absolution.

Tim Gallagher writes:

The bird is so iconic: big, beautiful, mysterious—a symbol of everything that has gone wrong with our relationship to the environment. There is such a sense of finality about extinction. I thought that if someone could just locate an ivory-bill, could prove that this remarkable species still exists, it would be the most hopeful event imaginable: we would have one final chance to get it right, to save this bird and the bottomland swamp forests it needs to survive.

Here is an easier story. A clear narrative arc. Only through the ivorybill’s apocalypse—the utter destruction of its world, its believed extinction—was the groundwork laid for its subsequent resurrection and, therefore, for our subsequent redemption. This fits more cozily into our thousands-year history of religious eschatologies in which an exalted and uncomplicated beginning always follows an ending. And it is for this reason, perhaps, that so many people quest for the ivorybill, hang on to the story of this bird. It is a symbol of hope, of the promise that the ornithologists of the late 1800s were right about this woodpecker—that we can’t possibly destroy a species. That story is too much to bear. The 2005 sighting reignited a sense of possibility, it inspired action, and it became a chance to give the ivorybill its rightful ending: the triumph of new life. And we would be the ones to give this gift.

And what of the three billion other individual birds who have vanished, whose disappearances are dispersed across species and ecosystems, whose deaths were forewarned but not avoided? What of the eight species of bird that were confirmed extinct in the last decade, among them the Spix’s macaw, the po`o-uli, the Pernambuco pygmy owl, the cryptic treehunter? What of the thirteen hundred species of bird that are facing extinction as these words are written?

How are these two eschatologies at play in our consciousness and in our behaviors? To what extent does our inclination to look towards a destructive future paralyze us in our ability to change our behavior in the present? Does the very notion of apocalypse bear the danger of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy? What are we to make of the disconnect between our willingness to believe these scientific warnings of a disastrous future and our unwillingness to act to change them? Is our ability to imagine the destruction of the planet rooted in our inability to see ourselves as active participants in the vital, breathing ecological systems of the Earth?

VI.

The fact that there are those who continue to avidly search for the ivorybill and those who have long accepted its extinction speaks broadly to the human tension between hope for the future and resignation to the idea that things will come to an end and perish: We both log the forest and attempt to protect it. We both mourn the loss of a species and continue the activity that will result in the loss of many others. And we both resist and implicitly accept the fact that our own survival, our own apocalypse, hangs increasingly in the balance. The disappearance of the ivory-billed woodpecker and other species become signs and omens of end-times that play out both mythically and scientifically in our collective consciousness.

At the end of Silent Spring, Rachel Carson writes: “We stand now where two roads diverge…. The road we have long been traveling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road … offers our last, our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of our earth.”

We come at last, then, to our own liminal state, caught between two eschatologies. On the one hand is the religious apocalypse, seen in our persistent, insistent, belief in a triumphant ending—one in which we will not only persevere, but thrive. We want to believe that we are worthy, that we alone can save the ivory-billed woodpecker, that we will come out the other side, righteous, free, and redeemed.

On the other hand is the scientific apocalypse: a destructive future in which humanity is to blame for the end of the Earth; a reality in which we must both bear the responsibility and suffer the consequences.

It’s important to note here that climate scientists would staunchly refute assertions that their work is in any way religious or prophetic. I would agree with them. Nonetheless, a scientific eschatology has come to exist within our cultural narratives, taking on power and influence that exists independently of the science itself. The science offers us clear, achievable solutions for lessening and possibly averting both current and future disasters, but we do not collectively act upon them. We read the latest IPCC report and then turn our heads away and continue in the very actions that the world’s best minds tell us have led—and will continue to lead—to drastic shifts in the balance of our planet, nearly all of which will directly and negatively impact humanity. Why?

Perhaps part of the answer lies in our predisposition to hearing eschatologies. While the data sets, predictions, and conclusions of science do not claim any final ending and are certainly not couched in religious language, we nonetheless are prone to interpreting them as such. Maybe the data is too painful or the solutions too large for our minds to comfortably hold, and so we seek another framework to hold this information for us. In the West, the cultural framework that we often turn to in these moments is biblical: God has ended the world before and God will end it again.

We are a species that translates data into narrative; hypotheses and theories into story. Proof of warming oceans, disappearing species, and raging wildfires falls into our cultural consciousness and lands in an apocalyptic tale. By placing “climate change” into this context, we both find space for it to be held apart from ourselves and turn it into a story of inevitability. We paralyze ourselves into resignation and fix our gaze on a future that looms large and dark, continuing to take steps towards it.

Thus, Jewish and Christian eschatologies fail to offer us a way out, fail to hold us accountable, fail to check our arrogance. The eschatologies that we create around scientific fact fail to capture our imaginations and fail to provide us with narratives of possibility or stories that are grounded in love and relationship.

What, then, of a third way, one that is not linear, that does not pull us into an inescapable future? What if instead we came—collectively—to love the ivory-billed woodpecker, the sage grouse, the osprey? What if we could loosen the grip of arrogance and control and come to see our salvation in the salvation of birds? What if we didn’t jump straight into resignation but turned away from a future ending and toward the present, toward that which is immediately around us? Perhaps this is the real work to be done, here, now. Perhaps we can change the question from “How can I stop the world’s oceans from warming?” to “Where and how can I place my body, my senses, my mind, into direct relationship with the living world?” Such an orientation invites the possibility that at any point we might choose to engage differently with both endings and beginnings. We might turn away from the linear path—the image we have formed of the inescapable future—and ground ourselves in the present, where we can meander and explore, becoming open to the relationships that surround us, that we inhabit in every moment.

Where can we find the tellers of these sorts of stories?

There are many. One might look to Robin Wall Kimmerer and her ethic of reciprocity, Wendell Berry and his sabbath poems, W.S. Merwin’s palm garden, Lauret Savoy’s terrains of memory. They are among the great chorus of voices that seek to turn our attention away from the inevitability of the future and place us firmly in the now. These are the voices who say: the story is being written. It is, in every moment, weaving itself through you, and its every thread is available for you to pick up and follow. It is in the songs of birds, the whisper of grass, the crash of waves, the rustle of leaves.

Perhaps the urgent whisper of these stories need not fall silent alongside the calls and kents that are no longer heard in the trees.

Photo by Arthur A. Allen

- Dead hackberry fed upon by ivory-billed woodpeckers, June 1937. Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, US Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records, Mss. 4171, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Nestling ivory-billed woodpecker on J.J. Kuhn, March 6, 1938. Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, US Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records, Mss. 4171, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Cypress on Rainey Lake, May 1939. Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge, US Fish & Wildlife Service, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker Records, Mss. 4171, Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

The Poet and the Palm Tree

The poet W.S. Merwin spent the last four decades of his life on Maui, restoring a plot of abandoned land that would become one of the most diverse and expansive palm tree gardens in the world. His poems are living witness to the care he offered to this land.