Anna Badkhen is the author of seven books, most recently Bright Unbearable Reality, which was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award and for the 2023 Jan Michalski Prize for Literature. Her awards include the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Barry Lopez Visiting Writer in Ethics and Community Fellowship, and the Joel R. Seldin Award from Psychologists for Social Responsibility for writing about civilians in war zones. Her essays have appeared in New York Review of Books, Granta, Harper’s, The Paris Review, Orion, and The New York Times. Anna was born in the Soviet Union and is a US citizen.

Igor Bobyrev was born in Donetsk, Ukraine, in 1985. He graduated from the Donetsk National University with a degree in history. His poetry has been translated into several European languages. He is the author of two books.

Charles Digges edits Bellona.org, the website of the Norwegian environmental group Bellona, where he has reported on Russian and East European nuclear issues for the last two decades.

Iya Kiva is a poet, translator, and journalist. She was born in 1984 in Donetsk and moved to Kyiv in 2014 because of the war. She now lives in Lviv, Ukraine. Iya is the author of two collections of poetry, as well as a book of interviews with Belorussian writers. Her poetry has been translated into more than thirty languages.

Olga Livshin was born in Odesa, Ukraine, and lives outside Philadelphia. Her poetry and translations appear in The New York Times, Ploughshares, and other journals. She is the author of A Life Replaced: Poems with Translations from Anna Akhmatova and Vladimir Gandelsman.

Oleksiy Vasyliuk is a Ukrainian environmentalist specializing in protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Since 2004, he has served in the Animal Monitoring and Conservation program at the Institute of Zoology of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Oleksiy is the head of the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group and has initiated the creation of more than sixty new protected areas in Ukraine.

Zarina Zabrisky is an American author and journalist currently reporting on the Russian war in Ukraine. She is a war correspondent for Byline Times (UK); Euromaidan Press, a Ukrainian online English-language newspaper; and Fresno Community Alliance (US). She is the author of three short story collections, the novel We, Monsters, and the collaborative poetry collection Green Lions.

Fyodor Badkhen is a storyteller. They were born in Russia and live in Philadelphia.

How to write about the environmental fallout of an ongoing, active shooting war? In the first eight months after Russia launched its latest invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Ukraine’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources recorded 2,239 cases of environmental damage it blames on the war. The ministry said fighting has placed under threat a fifth of Ukraine’s protected areas and around 600 animal species and 750 species of plants and fungi. Ukraine’s government estimates that more than 1,700 square miles of forest lie within occupied or hostile zones, with 63 separate forestries under occupation. Speaking at the COP27 climate summit last November, the minister, Ruslan Strilets, estimated the environmental damage at more than $39 billion. “The Russians,” Strilets said, “have turned our natural resources into military bases.”

Ukraine is now one of the most heavily mined countries in the world. Like the United States, Russia is not a signatory to the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty, but Ukraine is—yet Human Rights Watch reported in January that Ukrainian forces fired butterfly mines at Russian troops during the Russian occupation of Izium. Elsewhere, unexploded ordnance ticks away in forests, on beaches, in the streets, in the sea; some of these devices may not detonate until decades from now. What happens to the environment when you blow it up? What is the long-term chemical aftermath of “fires at fuel depots,” “blown-up reservoirs of dangerous chemicals,” “damaged gas pipelines,” “destroyed vessels in the Black Sea area?” When will we learn if hydrogen sulfide leaked into the Sea of Azov following the continuous Russian bombardment of the Azovstal Steel Works in Mariupol, and if it did, how much? Who can calculate the ecological damage caused by nine years of war, and counting, in the coal mine region of Donbas? What’s in the “brackish, salty water” of Mykolaiv, which, writes Tim Judah in The New York Review of Books, “cannot be drunk and corrodes pipes—they have been springing leaks everywhere,” and what does this toxic water do to the people and plants and animals and soil that come in contact with it, and how long will it keep doing it? Why did atomic scientists move the hand of their Doomsday Clock ten seconds forward? And what is the impact of the ecological devastation—and of its relentless threat—on the soul and the mind? “Any war is toxic and destroys the image of the world in which specific people live,” the poet Iya Kiva wrote me from Lviv.

It is impossible to truly assess the immediate and long-term ecological damage of a war that has no end in sight, in a heavily mined country where the toll of the dead and the injured mounts daily and the targeted destruction of infrastructure amounts to ecocide. If war is a dragon, as Zarina Zabrisky writes, then we can only see the earth the dragon has already scorched, name the victims it has already devoured. We can only see snapshots, a scale here, a talon there. We can only surmise the savage potential magnitude of the thing.

Snapshots, then. I asked five writers—poets, journalists, ecologists—to tell us what they see—from the contaminated Red Forest of the Nuclear Exclusion Zone at Chornobyl, from an artist’s studio in Odesa, from Lviv, from Izium, from an apartment in the occupied Donetsk … I hope their contributions, presented here, coalesce into a kind of panoramic testimony, a shrapneled bearing in time.

This composite piece is a macabre kineograph. Some of the damage already done is irreversible. And it can still get worse. May this grim mosaic serve as a warning rather than a dirge.

—Anna Badkhen, February 2023, Philadelphia

Ecocide

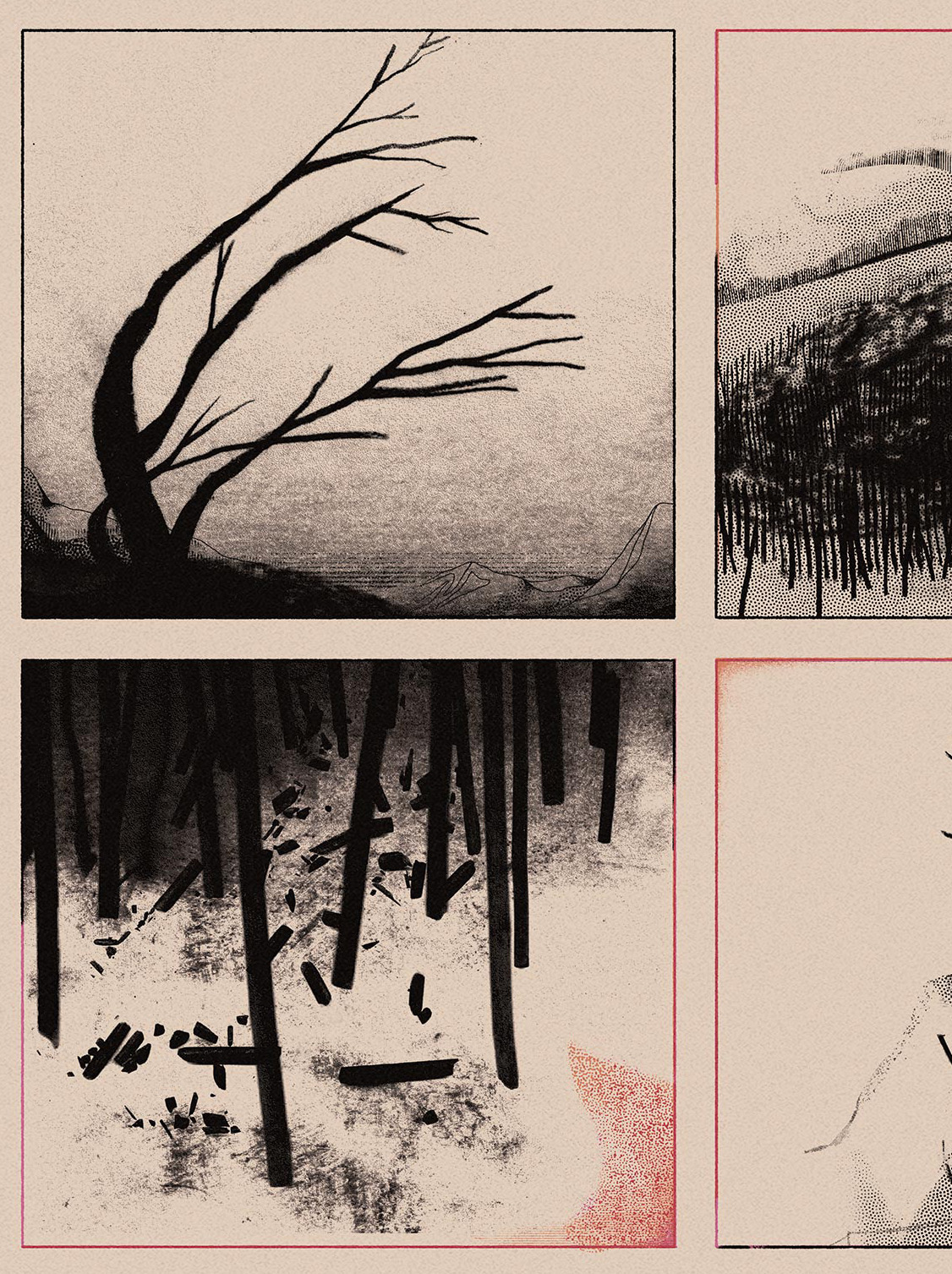

War is always the end of the world. The landscape we describe as “my country,” “my town,” “my home,” always dies, whereas the people who live in it still have a chance to find safety. In the face of war, nature is always defenseless and unarmed. Since, for instance, trees, grasses, and flowers cannot pull their own roots out of the Ukrainian soil, they cannot run away to safer places, becoming refugees. This is precisely why photographs of wounded, broken, charred, and destroyed trees are the signs of death by which the entire world recognizes a war. Does anyone count the number of plants killed and wounded in a war? I am afraid not. Is it possible to rebuild a single demolished tree? No, all we can do is plant a new one. If the earth allows us, if the earth forgives us. The environment does not have a chance at winning a war, it always loses. And the loss of ecosystems and of processes established in biocenosis are irreversible and innumerable, because all war can do is rape the body of the earth, filling it with rockets, shells, bombs, mines, weapons, military equipment as if it were a woman’s vagina. So that for a long time hence, for years and years, the earth cannot give birth, cannot be a home for living beings, cannot shelter them. And none of us know when the earth will find the strength to recuperate, and whether it will recuperate at all. The green backbones of our forests, the strong teeth of our mountains, the supple bodies of our rivers and seas, the skin of our steppes, tender like feathergrass, the elusive breath of our air—they are all sullied, befouled, and poisoned by war.

—Iya Kiva, tr. Anna Badkhen

Nature’s Revenge

I wake up from the piercing wail of an air raid alarm, the putrid stench of a peat swamp burning, the sour taste of metal in my mouth. I’m in Ukraine, twenty-five miles from the Chornobyl nuclear power plant. The murky air and smokey skies remind me of the days of the San Francisco Bay Area wildfires: a face mask, itchy eyes, shortness of breath. The wildfire in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone presents a different risk—especially if it reaches the Red Forest.

In 1986, the worst nuclear disaster in history turned a pine forest two miles west of the power plant into orange, golden, and rusty red horror. The windblown radioactive dust killed not just the chlorophyll molecules in the pine needles but the whole ecosystem—a complex living network of trees, animals, birds, reptiles, and insects. The Soviet leadership knew that if the Red Forest burned and released the deadly particles into the atmosphere, more areas would be affected. But, in a rush to bury the poisonous trees, the rescuers forgot to measure the depth of the grave. The new forest growing atop the remains absorbed from the underground waters cesium-137, strontium-90, and plutonium-238, -239, and -240. The half-life of plutonium-239, the most toxic of these radioactive substances, is twenty-five thousand years. This means that for the next twenty-five thousand years, if the Red Forest burns, the wind will carry inhalable death far and wide.

In 2022, during the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian military dug trenches in the most polluted areas of the Red Forest, apparently unaware of the rules of conduct in the contaminated territory. They raised radionuclide dust from the depths of the soil. Their shelling started wildfires. They hunted radioactive deer.

Serhiy Kireev, head of the Ukrainian government agency responsible for the radiological safety of the exclusion zone, told me that the digging likely released isotopes of plutonium and transuranium, and there is a high probability that some of these nuclides made their way into the soldiers’ bodies. Spontaneous combustion occurred in several villages that have been abandoned since the Chornobyl disaster and the surrounding forest. The Russian soldiers probably inhaled radioactive contaminated smoke.

In folk tales, the woodland is the portal to the world of the dead, a mysterious realm of the shadows of ancestors and mythical creatures. In Ukrainian lore, this realm is protected by a fiery flying serpent perelesnik and the souls of stillborn children poterchata, mermaids Mavka and witches Solokha, magicians molfars and werewolves vovkulaks. In Nikolay Gogol’s gothic horror story “Terrible Revenge,” which combines Cossack history with elements of folklore and fairy tale, a villain violates the laws of humanity and the harmony of the world. The nature then turns on him: “the trees, girdling him with their dark forest and as if alive, nod their black beards and stretch out their long branches, trying to strangle” the villain. In the real-life nightmare of the Red Forest, the violated land took vengeance on the invaders, poisoning them with deadly aerosols that cause lethal diseases. Ancient lore aligned with science and the forest itself to guard the homeland.

I think of Ukrainian ritual embroidery. Simple ornaments. Hidden symbolism. A tree: the triumph of life over death. Pine needles: eternal life. The color red: sun, fire, blood, life. Cleansing from evil. The Red Forest lives on.

—Zarina Zabrisky

A Routine Armageddon

The hostile military takeover of a nuclear power plant could mean the end of the world. But recently, Rafael Grossi, the head of the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency, fretted that it did not. Or at least that we no longer think it does. What was bothering him was that warnings of the danger of having Europe’s largest nuclear power plant getting swallowed by the war in Ukraine had become a matter of “routine.”

Since March 2022, when Russian troops took the Zaporizhzhia nuclear complex in southeastern Ukraine, Grossi has been trying to negotiate an agreement between Kyiv and Moscow to make the plant off limits to military assaults. He hasn’t succeeded. This leaves six Soviet-built reactors, each with eighty tons of uranium inside them, and some fifteen thousand spent nuclear fuel assemblies vulnerable. Though these reactors are of a more modern design than the dinosaur that exploded at Chornobyl, they are nonetheless vulnerable to Fukushima-like meltdowns as artillery strikes sever power to their cooling systems.

To be fair, there’s not much Grossi can do but ask nicely. The IAEA is an oversight body that has no authority to enforce anything, much less a ceasefire. But the effort recognizes that the world is faced with a unique new threat—the potential weaponization of an atomic energy station.

That’s not exactly what the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists had in mind in January, when it reset its famous calculus of nuclear dread, the Doomsday Clock, to ninety seconds to midnight—the closest we’ve ever been to Armageddon. But Doomsday doesn’t always come packaged as a mushroom cloud. The slow creep of a radioactive accident at Zaporizhzhia would be subtler, settling stealthily into the bones of generations and spreading contamination across Ukraine, Europe, and, ironically, Russia, depending on which way the wind blows.

Preventing such a thing isn’t really done with more tanks or more troops or more threats. It is rather a bureaucratic process, involving tedious negotiations over prosaic points of safety. The eyes tend to glaze over. Which is precisely Grossi’s fear. But this tedium could resolve one of this war’s central—and most far reaching—dangers. In this one instance, let us recognize the slow, the boring, the routine. And hope that it pays off.

—Charles Digges

Apropos

Apropos the environment, we haven’t had water since February.

—Igor Bobyrev

Anthropogenic Disaster Zones

When Ukrainians speak about the environmental consequences of the war, they often mention ruined military equipment. But while burnt-up tanks and military vehicles make a striking spectacle, they are, essentially, merely armor that won’t be going anywhere. What are the factors that lead to truly catastrophic pollution?

Russian troops have repeatedly committed acts of ecoterrorism: They have sent cruise missiles to places where dangerous substances were stored. In the first months of the war, Russian missiles destroyed both working oil refineries and many major fuel depots in Ukraine. They have bombed gas pipelines and ammonia storage facilities, warehouses of flammable substances and chemical fertilizer depots, and at least thirty chemical plants. Burning such facilities essentially turns them into chemical weapons. Rockets have also destroyed water treatment facilities in Ukraine’s cities.

Each munition is a metal shell stuffed with a mix of chemicals. During an explosion, a chemical reaction occurs inside the shell, rupturing the metal casing into tiny shards. A 120-millimeter artillery shell bursts into up to 2,350 fragments, while a 151-millimeter howitzer shell explodes into up to 3,500 fragments, each weighing more than a gram. Different types of munitions contain different types of fuels and explosives, but all of them include heavy metals and sulfur. Heavy metals accumulate in the soil, are absorbed by plants, and find their way into the human body, where they can remain for decades, potentially causing gastrointestinal and kidney dysfunction, nervous system disorders, vascular damage, immune system dysfunction, birth defects, and cancer. Some of the chemicals in a projectile don’t combust during the explosion; this means that sulfur may fall directly on the ground. When there is fog, dew, or rain, steam rises from the earth, turning sulfur into sulfuric acid, which can burn seeds, plant roots, and all the small organisms that live in the soil and support plant life. Wind carries the acid to other areas, where it falls back to the ground as acid rain. Think of battlegrounds as territories scorched by acid. Regardless of where the shells explode—at the site of firing, in a military warehouse, or even inside a tank—100 percent of the chemical composition of the ammunition ends up in the environment, accumulating in the soil and getting into the water supply.

Russian troops intentionally wreck cities and towns. Millions of bombed homes and infrastructure in destroyed cities have become trash heaps. The war is turning prosperous, ecologically safe regions into anthropogenic disaster areas, as polluted as chemical waste dumps.

—Oleksiy Vasyliuk, tr. Olga Livshin

“I Hear a Very Gentle Sound”

By the side of a narrow path in liberated Izium, shards of emerald-green wine bottles sparkle in a trench. The pit gapes like a mouth of a monster and I want to snap a photo. But a close-up shot might cost me a leg, an arm, or my life. The retreating Russian military are booby-trapping roads, fields, even dead bodies—to sow fear and stop Ukrainians from returning to their land.

Ukraine is one of the world’s most heavily mined countries. Forty percent of Ukraine is mined—nearly a hundred thousand square miles, the largest territory in any single country, a chunk of land the size of Wyoming—even though Ukrainian sappers have removed nearly eighty thousand mines and explosive devices as of May 2022. Land mines have turned about 10 percent of this largely agrarian country’s farmland into minefields. Undetected, unexploded ordnance remains mortally dangerous for decades. Underwater mines destroy the marine life in the Black Sea, where mines and sinking ships have killed thousands of dolphins. Near Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, wild boars, dogs, or foxes have triggered six land mines.

I watch a sapper unit manually demine a field in the Kherson Oblast. They move slowly, as if dancing to the gentle sound of their metal detectors. The extracted mines, piled by the blown-up bridge, look like jagged dragon teeth, metallic hellish seeds.

I always see war as a dragon. The dragon craves immortality. It destroys life. Its teeth will live in the injured soil, grow into an invisible army of killers.

In Odesa, by the Black Sea, the Ukrainian artist Mikhail Reva sculpts the war in his studio, translating the indescribable into three-dimensional objects. The “Russian World” series: Lovecraftian chthonic hallucinations, dense with symbolism. A grotesque, twenty-six-foot-tall bear and a matryoshka, the Russian nesting doll, both made with battlefield scrap from Bucha, Hostomel, Irpin, Mariupol, Kharkiv. To give corporality to the unspeakable, Reva erects funeral mounds from Russian cluster bomb shrapnel, jagged bits of exploded mines, rocket fragments, parts of rusty tanks. He deconstructs the habitual, warps space by cramming it to the brim with coarse structures. The war rips the very fabric of humanity; the curved claws, toenails, and teeth of Reva’s creations tear through the mental realm and dig into the unconscious, attempting to solve the puzzle of death. Jarring shapes explode the calcified meanings.

I tell him about the war dragon and he sees it. From the roof of a Russian armored vehicle found in Bucha, a town that has become a symbol of Putin’s atrocities and Ukraine’s resistance, he welds a thirteen-foot-tall dragon’s skull. I am glad: his art, like folk tales, gives us the means to process the horror. It rebreathes sense into our collapsed universe. A ritual, an initiation, a catharsis. A rebirth. A gentle sound.

—Zarina Zabrisky

120,000 birds

The territories that Russian forces captured in 2022 (including those already liberated by the Ukrainian army) make up more than one-sixth of Ukraine. They are situated alongside the border, in the north, east, and south of the country, parts that also happen to be home to protected areas created since the late nineteenth century. In 2022, Russian forces occupied two biosphere reserves, eight nature reserves, seventeen national parks, and more than nine hundred natural monuments. At the time of this writing, most of these sites are still under Russian occupation.

The Askania-Nova Biosphere Reserve, one of the most famous in Europe, is among these vulnerable sites. Founded in the steppe in 1898, Askania-Nova is home to numerous populations of steppe animals from all over the world. It has housed zebras from Africa, saiga antelopes and Przewalski’s horses from Asia, and even bison from North America. There is also an arboretum that is more than 130 years old.

Askania-Nova has been nominated for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List. If the war destroys it, it may be impossible to restore its natural treasures, which were carefully maintained from 1898 to 2022. At this time, Ukrainian ecologists are not aware of any damage to the reserve.

The Black Sea Biosphere Reserve is also currently under occupation. One of the first areas in the post-Soviet states to receive a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve designation, this reserve contains lakes, islands, and shallow waters that are home to more than 700 plant species, up to 3,000 species of invertebrates, and 457 species of vertebrate animals; more than half of the species are protected. In summer, the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve becomes the largest breeding ground for the seabirds of Central Europe. In the fall, it is the landing site for the largest concentration of birds flying to Africa from the northern and central parts of Europe for the winter. Some of them remain here through the winter, and the reserve becomes the wintering grounds for up to 120,000 birds, the largest concentration of birds from Central Europe. Altogether, between 300,000 and 500,000 birds winter along Ukraine’s Black Sea coast. Military actions create the risk of disrupting natural conditions for the reproduction, migration, and wintering of wetland birds, affecting tens of thousands of animals.

Some species of plants and animals are at an alarming risk of becoming extinct. Most Ukrainians learn in elementary school that ours is the only European nation with a substantial steppe ecoregion, an area that covers approximately half of the country. Approximately one-third of the species in Ukraine’s Red Data Book, the national list of endangered animals, plants, and fungi, are found only in the Ukrainian steppe. The same is true of one-fifth of the species protected by international agreements in Europe. For example, the Tapinoma kinburni ant, the sandy blind mole rat, and twenty-one species of plants unique to Ukraine are currently in combat zones.

The Russian forces use an astonishing amount of ammunition. Former battlefields are obliterated landscapes. Unexploded ordnance is left behind, along with land mines. These areas will probably be abandoned for a long time. During this time, nature will recover, which may lead to the emergence of wilder, richer ecosystems. However, there will be no one to fight the dangerous invasive plants in abandoned fields and destroyed settlements. As a result, these lands will become the largest nurseries for invasive plants in Europe.

It is too early to say what the postwar future holds for the nature of Ukraine. But one thing is clear: just like people, wild animals and plants cannot survive in places where shells explode or fires rage. Wild animals are fleeing their natural habitats and have been sighted in cities, where they stand little chance of survival. Wartime damage to ecosystems marks the beginning of long-term degradation. Its consequences will last for decades.

—Oleksiy Vasyliuk, tr. Olga Livshin

Poison

War does not end when the battles stop. War is a slow-acting poison that strikes at the now but aims at the future. It scatters its poison on the Ukrainian soil every day, every minute, without pause.

Carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, formaldehyde, steam, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, nitrogen, hydrocyanic acid vapors—this is how detonating rockets and artillery shells sound in the language of chemistry. Also sulfur oxide and nitrogen after the strikes on oil depots and chemical plants. Also white phosphorus from munitions fired by Russia. All of this ends up in the air, in the water, in the soil, and in the food chain, causes chemical reactions and provokes ecological devastation. None of this helps solve the problem of global warming. None of this, for certain, is the concern of Ukraine alone, since the cycle of matter knows no state borders.

People are relieved each time a strike on Ukraine’s infrastructure causes no human casualties, but from a non-anthropocentric perspective the situation appears different, because each strike releases chemical, toxic, and sometimes radioactive substances into the environment. Since 2014, the mines in the east of Ukraine have been flooded, and the poisoned water from the mines has been seeping into groundwater, drinking water, into rivers, and, therefore, into the Sea of Azov. This means not merely disease and death for the water, but also disease and death for people, animals, plants, microorganisms. Humans and animals that cannot be properly buried because of constant shelling transition from a space of love into a space of danger, from living beings into products of decomposition that poison the earth.

The glorified mythology of the Second World War, which supplanted the stories of genuine horror enacted on the territory of the former Soviet Union, did not leave room for the understanding of war as a massive ecological catastrophe. But today I see the catastrophe as clearly as St. John saw his Revelation.

—Iya Kiva, tr. Anna Badkhen

About the Animals

this poem

was written on assignment

journalists asked

to write it

[for their journal]

to tell them about the life of animals

about the environment

in our region

I thought then

that I could tell them

or simply think about it

I remembered the falcon

that I saw

in the courtyard next door

last summer I was walking to the shop

I always take this courtyard

to go to this shop

because [this is the closest shop

and besides] it’s [much] faster this way

[and also safer

especially when the bombing starts

though this fall

they hit the courtyard

[and earlier it also got shelled

a few times]

but still

it’s safer]

this time

I again took

the courtyard

and when I walked a few meters

I saw

that there was a bird lying on the ground

it was a very unusual

large bird

with beautiful plumage

I thought then that it was a bird of prey

that flew into the courtyard

and died here

though maybe it fell first

and then died

I don’t know for sure

this falcon was lying on its back

I approached it in order to

see it better

and photograph it

I always photograph

birds and animals

especially rare ones

recently I photographed squirrels

squirrels got into our courtyard

and ran past the window

I thought then

that before the war

we had no squirrels

and now there are many

in every courtyard

anyway while I was studying this bird

I thought that birds of prey

also weren’t here before

they used to fly somewhere over the steppes

and now they fly over the city

I thought that was really weird

I went to the shop then

and when I returned

the falcon kept lying there

I thought then

how strange that no one yet had taken

and eaten it

[the cat hadn’t eaten it]

once I saw

a dog drag a cat

apparently the cat wasn’t alive

I thought then

that the dog drags it

in order to eat

someplace

quiet inconspicuous

where no one will interfere with it

and so it needed that cat

a couple of times I chased away dogs

[that wanted to attack cats

and later attacked them regardless]

I [also] have a cat

and once in the beginning of the war

he ran away

went out into the street

I tried to catch him for a long time then

he didn’t want to come scratched a lot

I left him in the courtyard then

and when evening came

the cat went somewhere

and a pack of dogs started chasing him

then the cat ran back

and tried to climb onto the window

but instead he got scared

and climbed a tree

that grows in front of our window

then I chased away these dogs

but the cat was very frightened

and sat there until morning

and meowed

and then [it was already morning] he jumped down to our window

[I was very worried for him then

anyone would have been worried for him]

after that incident I never allowed him back into the courtyard

half a year later

a shell hit our apartment

and we [again] looked for the cat for a long time

we decided that he’d run off

and when we found him

he was in the toilet

shaking a lot

was terrified

and when I picked him up

he seized hold of me

a few days later

we moved to another apartment

last summer they bombed us again

and then the cat hid under the table

I thought then

that the first time

they had bombed us

the cat also hid under a table

though it was a completely different table

then I picked up the cat

and took him to the toilet

it was really hot then

hard to breathe

at that time we had no water at all*

they turned off the water

for 43 days

the cat and I then sat in the toilet

and when my mom came home

she laid down under the table

where the cat had been hiding earlier

and then when they stopped shooting

my mom went to get water

at the time we got water

at a boiler room next door

and it was still the middle of the night

we had no electricity then

and my mom walked across the courtyard

and when she arrived

it turned out there was a line already

people had lined up for water

an hour later my mom returned

and then they started bombing us again

and my mom again lay

there under the table

*speaking of the environment

last summer all of our reservoirs dried out

completely dried out

all the little rivers and streams

people were pumping water from them

December 20, 2022. Donetsk.

—Igor Bobyrev, tr. Anna Badkhen