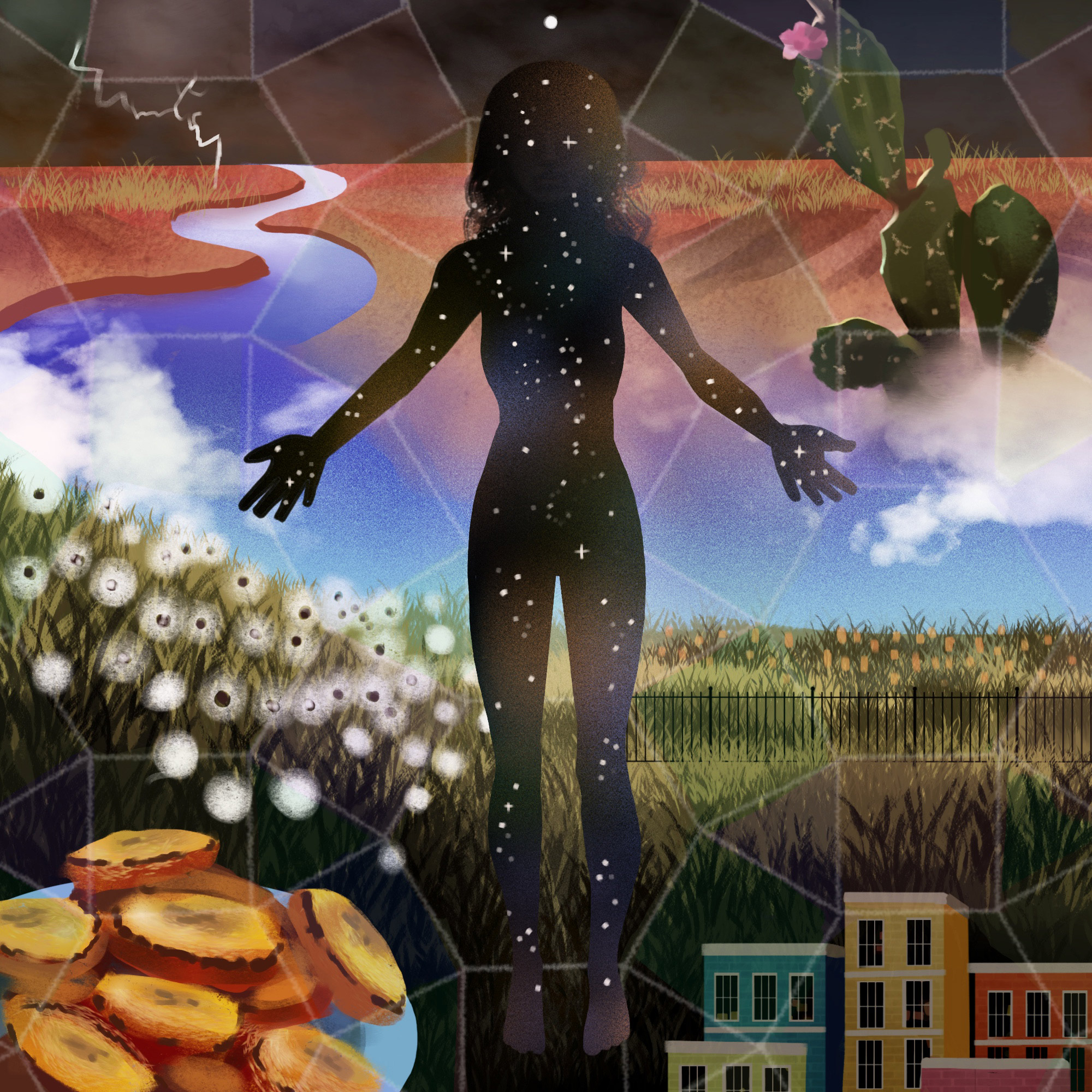

Makshya Tolbert is a Black, queer writer and land worker. She received a Certificate in Ecological Horticulture from the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems and is a member of the DAISA Enterprises team as a Communications and Community Specialist. As a 2015 Tom Ford Fellow, she worked with the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation, the Surdna Foundation, and North Star Fund to strengthen local food supply chains, and as a US-Italy Fulbright Scholar in 2019–2020, she studied food, slavery, and fugitivity at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy. She currently lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

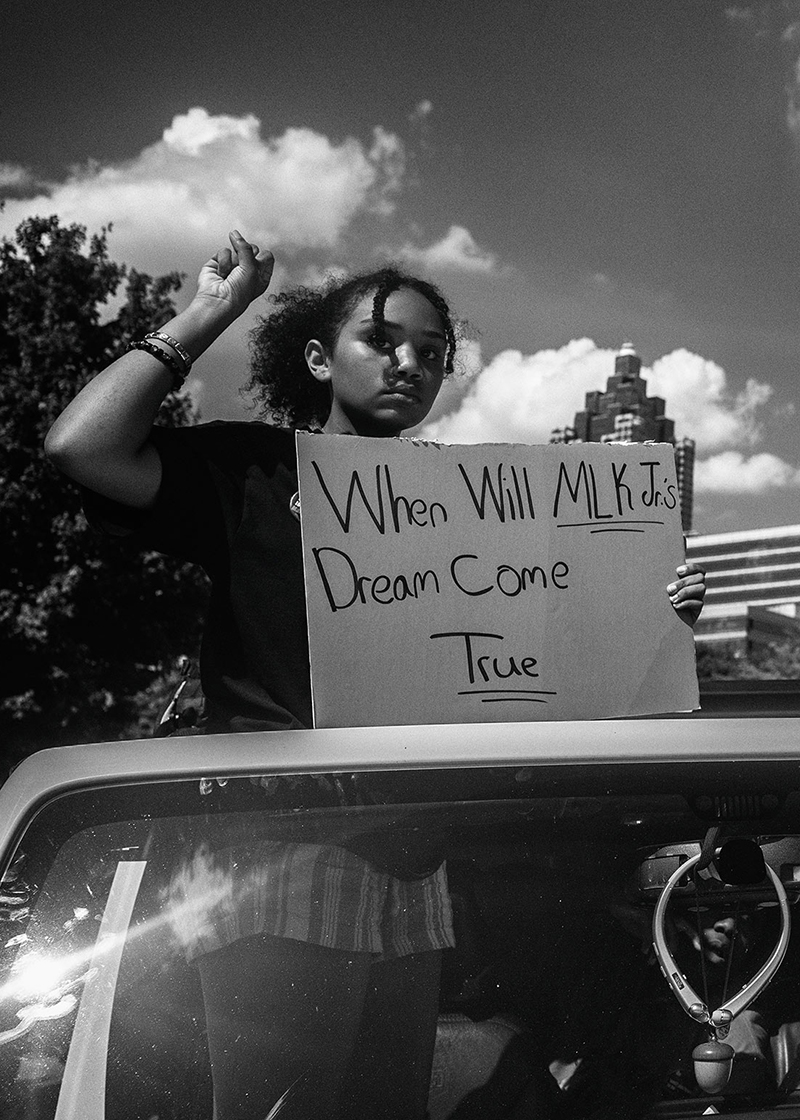

Sheila Pree Bright is an acclaimed fine-art photographer known for her series Young Americans, Plastic Bodies, and Suburbia. Her documentation of responses to police shootings in cities across the US inspired her book #1960Now: Photographs of Civil Rights Activists and Black Lives Matter Protests.

Makshya Tolbert wades into the liminal, haunted space that exists between water and Black memory. As she navigates Black lineages of thinking and practice, she comes to the meeting place of past and present, life and death, slavery and freedom, and embarks on her own return to water.

“I went down to the river to remind myself of the other language.”

—JJJJJerome Ellis1

I was born a few minutes from the Potomac River. Less than a month ago, I packed what I had and headed back to Virginia. I knew some of what I’d find there: oysters, northern water snakes. An array of fish that have made their way through centuries: bass, carp, herring, shad. I knew I’d revisit my family’s ghosts, and a river that was once home to a human and more-than-human ecosystem that could ensnare any enslaved Black person seeking safe passage.

Water carries an edge for me, seems to me a dying place. I moved my life from the Potomac River to the Pacific Ocean ten years ago and am just now finding my way back. This time I’m chasing the river, albeit terrified: chasing a lineage of Black watermen, a spillage between my family and the next, a different way of remembering.

I learned not long ago that Black people clung to oysters—a furtive refuge, but an honest one. I learned at that time about Black people’s insistence on place. Oystering a cosmology of work, play, and quiet. The cannery, a land of women working for what they could. I thought to myself that oysters must have reminded us of where and to what we belonged. Everything still there, hidden in plain sight.

I’m chasing a river instead of letting the river chase me. This time, I’ll live and drift along the Potomac, into the Chesapeake Bay, until I’m on the Atlantic again. As I plan my journey, a line from Martinique-born poet Édouard Glissant ebbs and flows, nudging me: “Do not fear the watery depths.”2

Why do so many of our crises shape themselves like water? I had run far from the Atlantic: I tried the West Coast, but the hypervigilance of fleeing still seethed through me. I imagined distance itself a refuge; I took myself to a small landlocked town in Northwest Italy and tried to remember who and what I love from there.

In the Mediterranean, another haint awaited me altogether. There, I found another reckoning, another displaced lineage. To leave one crisis was to enter another, or another part of the same. Thousands of refugees taking to water, moving across North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea, many prevented from closing the gap between fleeing and refuge. Everywhere in need of the possibility of flight. By the end of 2019, at least 1,885 people seeking refuge and/or asylum had been claimed by water, most having come from countries excluded from safe, legal processes for seeking asylum. All of their boats, crowded hulls. And then there were the ones that disappeared, ghost boats still haunting the waters, whose distress signals went unacknowledged and unanswered. The people on them are believed to have sunk. By the end of 2019, 413 people’s lives ended this way: unanswered, left without landings. Less and less seemed possible that year. Refugee boats and slave ships, both stalked by the hold.

Living in Italy drove me to a new point of grief. This is what it is to be haunted by water: you move and the ghosts wear different clothes. I learned how running is always still being chased.

In Bra, an inland comune of thirty thousand, I held this mostly alone—though, alone I was not. In the words of Nigerian poet Wale Ayinla, “I write this elegy in the presence of hundreds of ghosts / from my dreams. A strange horizon on a barren sea.”3

In Bra, I began to find the refuge of language, an anchor with which to steady myself. It was here that Dr. Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being reintroduced me to the range of the “wake”:

Wake: the track left on the water’s surface by a ship; the disturbance caused by a body swimming or moved, in water; it is the air currents behind a body in flight; a region of disturbed flow.…

Wake: a watch or vigil held beside the body of someone who has died, sometimes accompanied by ritual observances including eating and drinking.…

Wake: grief, celebration, memory, and those among the living who, through ritual, mourn their passing and celebrate their life in particular the watching of relatives and friends beside the body of the dead person from death to burial and the drinking, feasting, and other observances incidental to this.…

Wake; in the line of recoil of (a gun).

We don’t make up ghosts that aren’t already adrift.

Sharpe’s words slowed some of my internal panic. I began to stay with this feeling that my water fear comes from someplace dark and past and heavy. I heeded Sharpe’s insistence on what she calls the “orthography of the wake” and began to fathom her praxis of “wake work”: “imagin[ing] new ways to live in the wake of slavery, in slavery’s afterlives, to survive (and more) the afterlife of property.… a mode of inhabiting and rupturing this episteme with our known lived and un/imaginable lives.”4 My own life patched together pieces of slavery’s wake with some hope for a future memory. In Italy, spending as much time with water as my heart allowed, I saw the slave ship, the refugee boat, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean.

I felt undone by water. In Italy, and before, and after. My friends and loved ones sought watering holes and long days on Pacific Ocean beaches. Me? I sought navigational literacy—an ancestral ruttier made of water, night, and stars.

This is what it is to be haunted by water: we become afterlives spilling through our own fingers. Memory refuses to die and shows itself in ripples. Sometimes everything resembles the slave ship. Some nights, a ship out of a beached whale. Some nights, a shipyard of strewn parts. Some nights a shark is a hull, another death. I can conjure a slave ship out of anything.

I don’t believe I can leave the slave ship. Bayo Akomolafe tells me it’s okay to stay, that the slave ship is “a place of contemplation, as a site of reweaving our connections with grief and loss and trauma and tragedy.” I’m drawn to what Akomolafe sees in the slave ship: “a place to sit still, to sit within, to sit with,” where “a different sense of freedom can emerge.”5 His words are a steady drip, inviting me to stillness when refuge remains far.

For now, I split myself across the watery depths. Part of me has remained at shore, bridging disasters. In April 2020, no longer in Italy, I accepted a virtual invitation to be with water, in the gesture of holding space for La Montaña, a voyage of seven compañer@s setting sail from Mexico to Europe. The group planned to meet delegates from thirty countries to trade histories of pain, rage, and worldbuilding. I embarked in spirit only.

The rest of me has remained on the slave ship, safety trapped in my ancestral constellation, thousands of ships hoarding stolen life, “the most energetic space in modernity.”6 I think Akomolafe is right: that we never disembarked; that Clotilda “reached the American shore, [then] ate the shore … became the shore,” its entrails carried from the Alabama River into the hinterlands to build ideas of work and order; that we found somewhere to build another ship, another deck, another hold. All of it, a painful mimicry.7

I say a prayer of gratitude for the space between water and Black memory, sometimes measured in flight.

In prayer, I find myself at Dunbar Creek on St. Simons Island, Georgia. It is 1803. A story set as much in sky as in water. On the Atlantic, Black people refuse the slavery awaiting them in Georgia. Chained, and “free” of their captors, seventy-five Black people meet a shoal and disembark together. Everything becomes water, including this story. One version retells them walking into the water, singing as they submerge, in chains. Another says they flew up, up, and away—home.

“But what is home if not a floating horizon?”8 Where is home if not in the breathwork between water and sky? Breathing between water and Black memory, I place language at the shore.

Water decides I will become it.

Water, as it does, reflects. Water becomes a portal, something to sink into or float through. A wild to get lost in as we sing funeral songs, even when no sound comes out. I see how water becomes a life, then becomes a cemetery, then becomes an opening or another life. I pray it true that a future is already dreaming that we swim toward it. What soothes me is Toni Morrison’s reflection on water in her talk “The Site of Memory”:9

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. “Floods” is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.

With caution, I keep moving toward water. I continue finding water as water seems hell-bent on finding me. Telling me: there are more powerful possibilities than the hold. In tiny and large ways each day—a single droplet of water weighing down a leaf, a walk by a river to cry with—water shows me a sanctuary.

Water continues to be a wild, shapeless place. Somewhere resisting being marked or conquered, try as we will and as I did. So I write poems to heed Glissant’s call not to fear the watery depths. I witness how water holds Black memory—and laugh when language arrives late. As vocalist Miho Hatori reflects in her reading of Glissant’s poems, “I am learning how to stand between two worlds: the beauty of nature and the darkness of history. Sometimes the rift between them looks endless.”10

In Virginia, there is water from all angles. Every morning, until the next morning, the water in the air. Nearby, the Atlantic. Nearer by, the Rivanna. From land, what kind of witness of water can I be?

I begin seeing this in all of myself: my work with clay, the poems that want to be made through me, new forms of enchantment that take me elsewhere.11

In clay, I find another portal, a place to float between “our undoings and our becoming.” Working with water and clay, I honor centuries of intuiting with clay, before there was an Atlantic to cross. I hold how the Middle Passage tried to rub all of that away, sink us and our tools into erasure. Clay becomes a portal, a remembering project, a blueprint. A way to transmute violence into healing practice. A way to make the “future in the now.”12

In one moment, I slip wet clay through my hands and let it take shape between them. My mind reaches for the craftsmanship of David Drake, an enslaved Black potter who made thousands of pots throughout his life while enslaved at Pottersville and across the district of Edgefield, South Carolina. In reaching, I remember Drake’s carving on one vessel in particular, on which he inscribed, “I wonder where is all my relations.”13

And I am always taken back to water. Water becomes a window through which I see myself. So I settle, I float. To float is to anchor myself on water, to find home in what is there. Even if only for a moment. Both heavy and light, I feel the way the poet Christopher Gilbert writes in Across the Mutual Landscape: “I reach to touch / and the reflection touches me. / Everything is perfect— / even my skin fits.”14

Floating brings the Atlantic to light, floating allows me the spaciousness of being “the long black language that reaches all the way back.”15 Returning to water itself becomes an attempt toward “wake work,” my life itself the site of possibility.

I can barely remember the place I left so long ago, save names and a few dreams. Save my grandmother, whom we buried in Quantico, Virginia, beside the Potomac. Where water is the only salve.

In her memoir, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, Saidiya Hartman writes: “The country in which you disembark is never the country of which you have dreamed.”

I turn to water, welcome the familiar grief, and disembark.

Night Waltz with the Ever Given

can we go

off and steal

the atlantic

waltz

to the end

of the earth

dotted

susurration

blued

to incoherence

we become

undrinkable

water

a frictive

memory

seething

containers

in the night

animal

unable

to swim

water

only able

to swallow

we row wider

irreducible

algae shaped

a linger

we become

a hum

another

ocean

altogether

- JJJJJerome Ellis, “Bend Back the Bow and Let the Hymn Fly,” The Clearing (New York: Wendy’s Subway, 2021).

- Édouard Glissant, The Collected Poems of Édouard Glissant, trans. Jeff Humphries and Melissa Manolas (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

- Wale Ayinla, “Chronicles of Strangers in Dialogue (A Survivor’s Testament)” in To Cast a Dream (Miami: Jai-Alai Books, 2021).

- Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).

- Bayo Akomolafe, “Let Us Make Sanctuary,” Sep 30, 2020, Sounds True, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4XkmPxpogI.

- Bayo Akomolafe, “The Destruction of Earth and the Exploitation of People,” Facebook, April 22, 2021, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=814596539474111.

- Akomolafe, “Destruction.”

- Cherise Morris, from the essay “the cosmic matter of Black lives,” originally published in The Iowa Review, Volume 48, Issue 2.

- From Toni Morrison’s “The Site of Memory,” a talk published in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2d ed., ed. William Zinsser (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995).

- Miho Hatori, “Édouard Glissant’s Sun of Consciousness,” Bomb, March 12, 2020, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/%C3%A9douard-glissants-sun-of-consciousness.

- In his book Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own (New York: Crown, 2021), Eddie S. Glaude Jr. describes “elsewhere” as “that physical or metaphorical place that affords the space to breathe.”

- Saidiya Hartman in “Poetry Is Not a Luxury: The Poetics of Abolition,” a panel discussion with Saidiya Hartman, Canisia Lubrin, Nat Raha, and Christina Sharpe, along with Nydia A. Swaby as chair, August 10, 2020, https://silverpress.org/blogs/news/poetry-is-not-a-luxury-the-poetics-of-abolition.

- I Made This Jar: The Life and Works of the Enslaved African-American Potter, Dave, ed. Jill Beute Koverman (Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, 1998).

- Christopher Gilbert, “Now,” Across the Mutual Landscape (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 1984).

- Christopher Gilbert, “Horizontal Cosmology,” Across the Mutual Landscape (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 1984).