Natalie Rose Richardson was born in New York City to a long line of border-crossers and proud people of blended heritage. Her poetry and prose has appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry Magazine, Narrative, The Adroit Journal, Brevity, Orion Magazine, Arts & Letters, The London Reader, and Chicago Magazine. She has received awards, residencies, or fellowships from Poetry Society of America, The Poetry Foundation, The Newberry Library, The Luminarts Foundation, Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, and the National Student Poets Program, among others. She is a 2020 Pushcart Prize and a Best New Poets nominee.

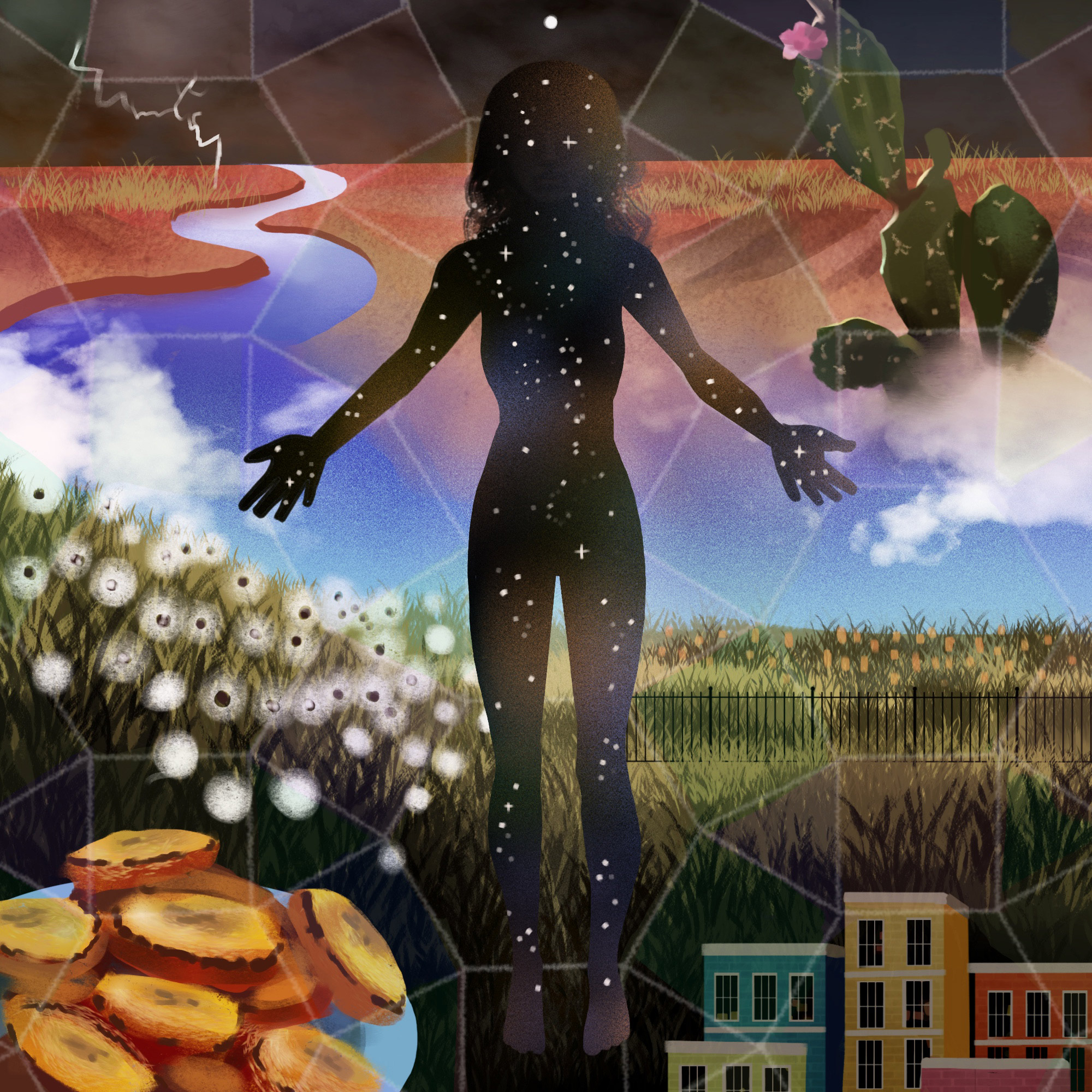

Jamiel Law is an artist and illustrator with a fine arts degree from Ringling College of Art and Design. His clients include The New York Times, The New Yorker, Slate, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Equal Justice Initiative, and The Guardian. Jamiel works as a designer with BUCK in Los Angeles and is represented by Writer’s House for his work illustrating children’s books.

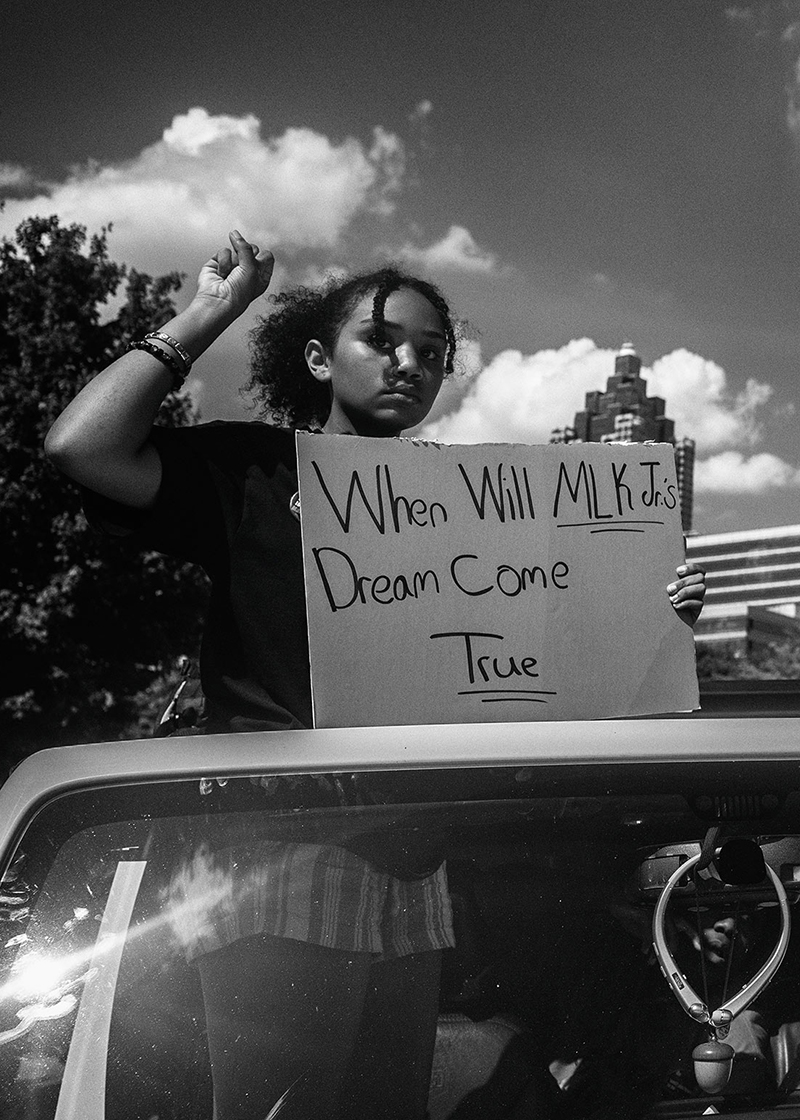

As Natalie Rose Richardson searches for her great-grandfather’s grave in a historically segregated cemetery, she confronts the American notion of paradise and the walls erected to protect it.

A Corner Less Kempt

I am visiting my great-grandfather’s grave. It is in Fort Wayne, Indiana, the city where my father grew up and where his mother still lives and works—behind the reception desk at FairHaven Funeral Home. I have come from Chicago to stay with my grandparents for a blazing week in late July, during which I will turn sixteen. The quiet local pool, cloaked by an assisted-living community, is closed Sundays. There is nothing else to do but visit the dead.

The cemetery, Lindenwood, is a sprawling 175 acres, a short drive from my grandparents’ subdivision. It is one of the largest cemeteries in the state, a vast orchard of stones. My grandmother and I walk leisurely through the cemetery, fulfilling the British landscape architects’ original intent for Lindenwood: that it be “parklike” and “picturesque” to the living, a model of eighteenth-century English principles. The dead wave us on below. We spend an hour wandering the pristine landscape and furrowing our brows over the map, on which my grandmother has written my great-grandfather’s burial section and plot number.

We do this to satiate the curiosity of my grandmother, who has been archiving my family’s ancestral records for the past three years. I know nothing about my great-grandfather but his name: Henry Richardson.

We arrive at a corner of the cemetery that is less kempt, devoid of lindens and sunken in the landscape, a place where rainwater and slush would collect. Unlike the acres behind us with gravestones and mausoleums of varied shapes, sizes, and colors, here there are only flat, gray stones scattered crudely in rows. Some of the rows house large, grassy gaps between the stones. I think of a mouth with missing teeth. Some stones have names and dates, and others are blank, as forlorn looking as the cinder blocks back in my parents’ yard.

My grandmother’s eyes narrow.

“I think,” she says quietly, “this must have been the ‘Colored’ section.” I bite my lip.

We wander the plot in silence. I read the names of every marked stone in every row, and then I read them again. I inspect every unmarked stone for markings that would not be immediately recognizable. The unruly grass pricks my ankles. Henry is nowhere we can read him.

Almost a decade later, I am in graduate school in Chicago writing an essay on my family’s history of interracial marriage. I find myself inexplicably piqued by my memory at Lindenwood, though I have not returned since I was first there at sixteen.

I dip a toe into the water: I call Lindenwood’s cemetery office. I explain to the peppy-voiced woman who answers that I am a graduate student researching my family history and I want to know whether the Colored section of Lindenwood exists. I am overly deferential, wary of confrontation, 160 miles away yet afraid of insulting the woman with truth.

“Goodness! I personally don’t know the answer—” Her chirpy voice is a bright curtain stretched taut across a dark room. “I’ll speak with our director and call you back. What is the section and plot number again?”

Later that day I discover a voice mail on my phone. It is the same woman’s voice. She says that if I choose to visit, she’ll give me some materials on Lindenwood that she’s assembled, including a map on which she’s located Henry’s section and plot number. She makes no mention of the absent gravestone or indiscernible plot.

“As for your question about the Colored section…” She pauses as though looking for her notes. “I spoke to our director and found out, yes, there was one; it was section 13, Paradise.”

I frown. Henry is buried in section 14.

She chirps on. “And in the ’50s, um, I guess they added another: Paradise Extended.”

The Prevailing Conditions

The word “paradise” is likely surprising in its derivation: from the Old Iranian term for “walled enclosure.”

At first this is troubling to me, if not alarming. I consider the white-sand beach that is America’s current commercial image of paradise, and I struggle to understand how—if we started at a “walled enclosure”—we arrived here. I think of walls, which make me think of closed doors and that old story I heard growing up: “there’s no room at the inn.” And when I think of there being no room in paradise, I imagine an exclusive resort beach overcrowded with sunburned, scantily clad people, a raucous crowd like Lollapalooza’s, where only those chosen ones who shelled out for expensive tickets have earned their place within.

What do we mean when we speak of paradise? Do we know—have we always known—that when we speak of paradise, we are summoning an ideology of barriers?

On further reflection, it seems almost obviously so. Most ancient and present conceptions of paradise exclude particular immoral or unworthy people: pariahs, the marginalized, the evil, the tainted. The white-sand beach is not accessible to everyone—if it were, would we not all be on it? Paradise, as we euphemize it now, is a place other than where we are, a place walled off from our earthly, quotidian struggles, accessible only once we’ve done something to earn our place there.

But who builds the walls of paradise? Who decides what and who will lie within—and, perhaps more importantly, outside?

“What constitutes paradise,” the landscape architect Ian H. Thompson writes, “has always depended on the prevailing conditions.”

Landscape architecture—a niche field consisting of craftspeople dogged by persistent misconceptions about their work—does not feature prominently in our dialogues about politics, though perhaps it should. Ian H. Thompson’s surprisingly lively Introduction to Landscape Architecture makes a strong case for the social and cultural roles that landscape architecture has played in our world since the first historical records of gardens and agricultural systems. Landscape architects are involved in the decisions of nearly every earthly space we inhabit, from community gardens to parks, industrial sites, motorways, dams, farms, refuse centers, cities, suburbs, and cemeteries. It is a field that considers how we ought to interact with our geography—a question steeped in both cultural theory and on-the-ground practices.

Because they are associated with death and the afterlife, it is easy to forget that cemeteries are politically relevant extensions of our living world.

Landscape architects generally agree on the following definition of “landscape,” used by the annual European Landscape Convention, which draws landscape architects from across the globe: “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors.” Landscape is perceived by people, an idea of the mind that to some degree is up for interpretation. Land has character: a moral ethic, a capacity to be lacking in integrity or piety, kindness or civility. It is an interaction of geographical and human factors, an interplay of geography with cultural and sociohistorical values. It is complex, it is fraught. Notably, this definition is consistent with other, more political uses of the word—as in a nation’s “moral landscape,” or a community’s “ideological landscape.”

The word “paradise” is frequently cited by landscape architects (it already appears three times in the first chapter of Thompson’s book). Thompson explains this by noting that landscape architecture, given its preoccupations with aesthetics and pleasure, is linked to “ancient dreams of paradise.” Steeped in the literal and metaphorical, landscape architecture is a field that marries our cultural conceptions of paradise with the geographies we inhabit.

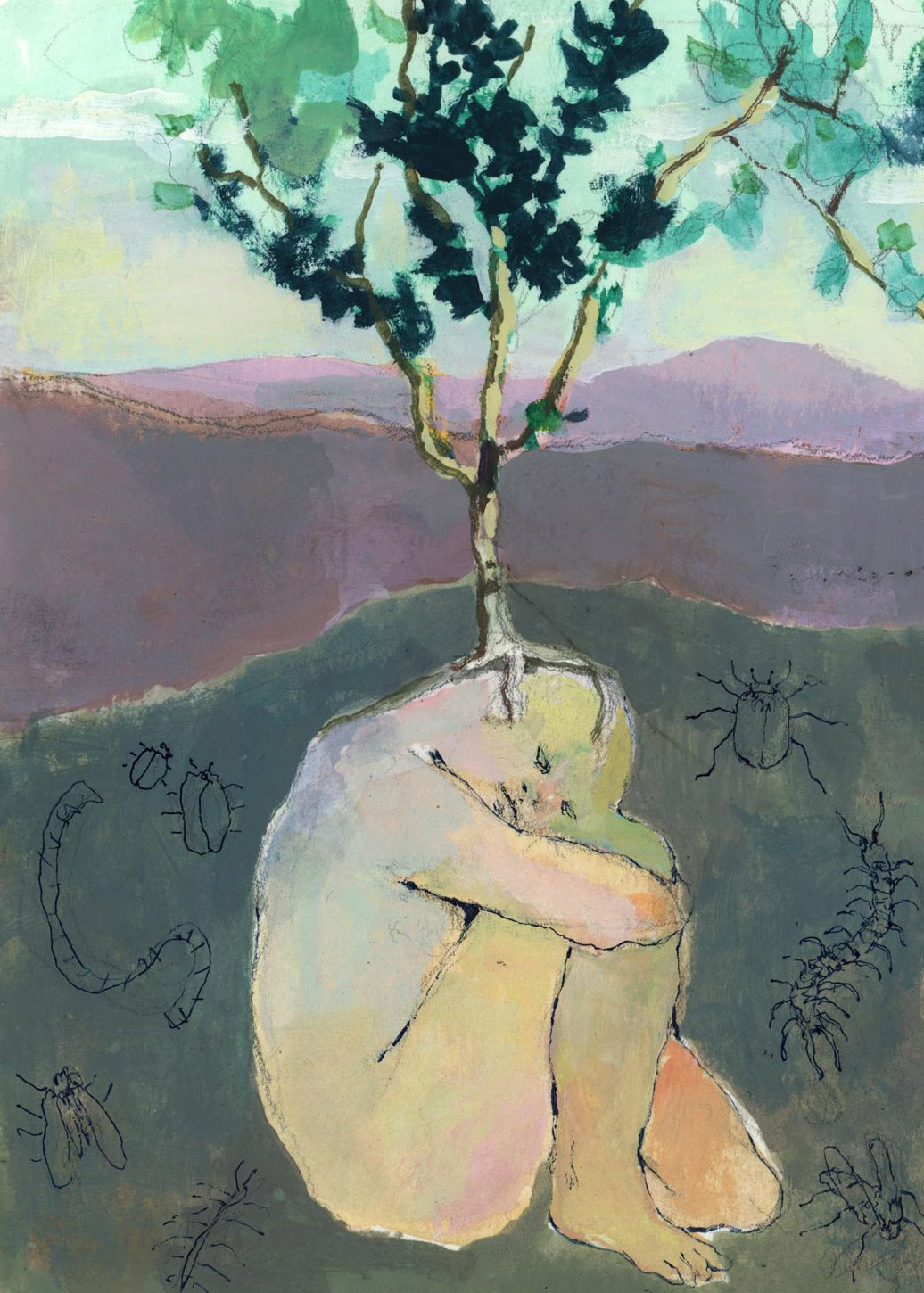

But like every marriage, it is not a simple union; it is not without its history. “Landscape planning,” Thompson writes, “does not begin with a blank slate.” Our geographic landscape, just like our ideological one, is a multilayered record. Architects have a word for this: “palimpsest,” which expresses the notion that even if a landscape is altered, traces of its history will remain.

Cemeteries are particular, strange landscapes. Many of us feel closer to the land in cemeteries than in any other common space. Here we watch the bodies of our loved ones lowered into plots cut from the earth. We plant flora near the stones of the dead, imagining their spirits rising liquidly through the roots and inhabiting the blossoms. Many of us choose to believe that our loved ones’ bodies will decompose in soil—marry with the earth—when, in fact, modern cemeteries are catacomb fortresses, underground stone grids as organized and unsentimental as city blocks.

Cemetery landscapes epitomize what most landscape architects agree is the root objective of their practice: to create paradise on Earth. The cemetery is a geography on which many of us impose ideas of heaven itself—our dead “resting in peace,” rising smokelike from their graves to a paradisiacal afterlife.

It is also a space that, generally speaking, we do not today associate with segregation. If there are borders in our cemeteries, they are the gauzy borders between the living and the dead. If there are fences, they are the wrought iron shields that guard the dead’s sacred space from our irreverent human life.

Even in past eras of more apparent national segregation, the segregation of cemeteries was often overlooked in broader political dialogues of civil rights and integration. For much of the twentieth century, cemeteries were not considered “public accommodations” by our federal courts and as such were not subject to civil rights protections. Even after they were technically integrated—as a by-product of a 1948 Supreme Court decision regarding land rights—cemeteries remained rigidly segregated along lines of race and religion. Because they are associated with death and the afterlife, it is easy to forget that cemeteries are politically relevant extensions of our living world.

While public spaces have grown more integrated since the mid-twentieth century, many cemeteries continue to lag behind. One keen example: in 2016, a chain-link fence that had racially segregated a cemetery in Waco, Texas, since its founding in the 1800s was removed by city order. Until only about a decade ago, this same cemetery was tended by two separate sets of caretakers—White and Black—who did not cross the chain-link border.

Arthur Paulison, executive director of Lindenwood Cemetery in 1977, penned integrationist descriptions of Lindenwood in his petition to the National Register of Historic Places, which I find archived as a pdf online. He wrote:

As an extension of naturalistic picturesque philosophy, Lindenwood exemplifies the principles of the landscape lawn cemetery. This park-like area departed from the traditional burial ground by eliminating hedges, fences, vaults, artificial materials, or anything that might appear as an obstruction in the landscape. Lindenwood in the picturesque tradition not only exhibits smooth expanses of unbroken lawn but also integrates open spaces with timbered areas…

Paulison’s description summons to mind an Eden for the living and the dead, in which there are no man-made divisions and even disparate topographies are integrated to form a world that is, above all, picturesque. The word “picturesque” appears throughout the document, as do “garden” and “gazebo.” Nowhere in Paulison’s portrait of Lindenwood’s field of dying is there mention of color lines—it is a picturesque example of the era’s racial astigmatism. Lindenwood was, for Paulison, a 175-acre paradise that illustrated the art of integration within a segregated nation.

As it turns out, the word “picturesque,” coined by architects and artists, has a different original definition than simply “pretty.” It originated as an artistic style. At the time of Lindenwood’s opening in 1860—the same year a clean-shaven Lincoln would be elected president and the country would dissolve toward civil war—the picturesque concept was spreading across America from Europe as a staunch reaction against neoclassicism, which emphasized order and formality. One encyclopedia defines “picturesque” as “an aesthetic quality” that is marked by a pleasing variety of “interesting textures” and—critically—“irregularity, asymmetry.”

Lindenwood is—like most American cemeteries—history’s chessboard of the dead. Color-segregated squares, like buried with like. Burial grounds are political, historically segregated extensions of American public spaces. Until recently, to enter a cemetery was to experience, as one Pennsylvania State University geography professor put it, the “spatial segregation of the American dead.” Historian Gary Laderman asserts in his book The Sacred Remains: “The cosmology of American political life is saturated with death and the bones of the dead.” Our burial grounds are monuments of fixed political ideologies.

Some corpses are commemorated in stone. Others lie namelessly in less-sacred corners of history.

In turn, cemeteries memorialize our exclusionist notions of paradise. It is one reason why cemeteries are so expensive. The median American burial costs almost $8,000—not accounting for cemetery fees, monuments, or markers, or miscellaneous expenses like obituaries and flowers—the price of buying one’s ticket to paradise. In some cases, there are even waiting lists for particularly desirable cemeteries; hordes of people wish to be buried alongside esteemed society names, to live forever in an exclusive, paradisiacal zip code. What’s more, cemeteries quite literally hold our blood ancestors, illustrating the ways in which we all are born from, and entrenched within, these exclusionist cultural landscapes.

But mine is a failed metaphor—for unlike the squares on a chessboard, our segregated burial grounds are starkly asymmetrical. They are evidence that certain corpses were granted access to “picturesque” plots, land, and burial arrangements that other corpses were not. Some corpses are commemorated in stone. Others lie namelessly in less-sacred corners of history. Where some entombed remains have for centuries been crowned by marble and guarded by wrought iron fences, others are only just now being uncovered—from where they were buried beneath bodegas, New York City high-rises, entire towns, tourist ports. In 2019 in Tallahassee, Florida, a cemetery of formerly enslaved people was discovered beneath the fairway of Capital City Country Club’s golf course—the emerald grounds of which were formerly a five-hundred-acre plantation. The ravaging and overtaking of Native peoples’ burial grounds has become so ubiquitously accepted that the “Indian burial ground” trope is now a popularized plot point in mystery novels and Hollywood films.

What American cemeteries and burial grounds illustrate is the fallacy that everyone can “earn” a place in paradise. Many people in history and the present—like my great-grandfather, Henry—were never granted the right to “earn” their place within our nation’s broader cultural ideal. Rather, the very conditions of their birth—“on the other side of the fence,” so to speak—foreclosed the possibility of their ever reaching it.

Paradise Road, Hurricane, Utah

Photo by Eliot Dudik

Searching for Paradise

I am looking at a photograph of Paradise Road. It is, according to the title, in Hurricane, Utah, and a congregation of mountains dominate the background of the image, their rock faces the color of a wound. Beneath the mountains is a tiny subdivision of identical homes and the dark, blank stares of their identical windows. In the foreground, in the center of the frame, is a cemetery. Almost identical in shape and size to the cluster of homes, it appears to us as a strange, inverted mirror of the subdivision. The lawns of the cemetery are flat and, unlike the native red-rock shrubbery elsewhere in the frame, unnaturally green. Pale rows of gravestones scar the ground. Paradise Road separates the cemetery from the subdivision—a neat, paved separation of living and dead. And where it touches the edge of the cemetery, Paradise Road makes one single loop around it—an unmarred border of cement that appears to both shelter the cemetery within it and hold the surrounding landscape at bay. The road seems to say, without saying: Here is the border of paradise.

The photograph is from a series called Paradise Road by the American artist Eliot Dudik. In 2013, Dudik began a road trip around America in search of all the roads called Paradise Road. The resulting exhibition, which features people, landscapes, and objects that Dudik encountered along the many different Paradise Roads, is a kaleidoscopic and jarring accumulation of scenes. In Paradise Road, San Diego, California, a man in a sweat-damp tank and loose jeans stands before a couple of beat-up cars parked on an empty plot alongside a dirt road. He squints upward toward the sun. On either side and behind him are hip-high brick walls, two of which appear unfinished. In Paradise Road, Baytown, Texas, one man sits in a folding chair on a suburban front lawn with a barber’s smock around his neck, while another stands behind him, razor in hand. And in the aerial shot Paradise Road, Edgemont, South Dakota, Paradise Road begins in the foreground as the pale dirt driveway of a modest white house before it crosses beneath a wire fence into a vast field, where it fades like a dream to nothingness.

“Personally, this dream seems to continually shift as new desires, obstacles, and realities become apparent,” Dudik is quoted as saying in one NPR article. The project began after the recession in 2008, when ideas about the American Dream were at the forefront of the national imagination. “In many ways, the United States is a changed landscape since then,” Dudik says, “but in far too many ways, it hasn’t changed at all.”

His photographs beg the question: Does paradise really exist?

What I am asking now is: Do we even want it to?

It is difficult to speak of paradise. Much like the language of American racism, the language of paradise is a rocky and precarious landscape, one that I wish to tread lightly through yet also thoroughly excavate. The meaning of paradise has been appropriated and manipulated by people in power throughout history to engender fear and loyalty. To build faith, to oppress.

That we have come to euphemize “paradise” as the platonic, virtuous ideal—that our language has slipped from speaking explicitly of borders to speaking of what’s most desirable—is simply proof of our exclusionist American ethic. Inherent in our notion of the ideal are walls of separation.

It is also difficult to speak of segregation, American racism, and paradise in the same sentence. This is, however, the point. The terrible truth is that paradise was—is—enacted at Lindenwood. Sections 13 and 14, where Henry is buried, are a kind of paradise: they are walled enclosures, gardens that nod, however troublingly, to a particular moral ethic. The problems of which I speak arise when particular, powerful groups with harmful agendas are the ones who define and decide a culture’s borders of paradise. We are lazy, cruel architects, prone to error and discrimination. Toni Morrison writes in her novel Paradise: “How exquisitely human was the wish for permanent happiness, and how thin human imagination became trying to achieve it.”

“I have never been particularly interested in slavery,” Wendy S. Walters begins her essay “Lonely in America,” the opening essay of her book Multiply/Divide; “perhaps because it is such an obvious fact of my family’s history.” Walters’s essay probes the troubling fact that a slave cemetery was discovered beneath the cobblestones of her New England town. In the piece, she attempts to illuminate some of the contradictions about American identities and aspirations.

Paradise is a palimpsest: a landscape on which we are constantly rewriting new cultural meanings atop the old; shadowed yet still visible.

“There’s … a lot of pain in history and present context of America,” Walters is quoted as saying in one literary review. “Multiply/Divide, for me, is an attempt to figure out where the pain is located in these historical moments and historical records that we are familiar with.”

Like Walters, I do not wish to simply point out a “buried” history of America—I accept it as a premise. That some people’s histories are lauded while others’ are intentionally neglected and erased is not a nuanced discovery in America. My true desire is to gather, interpret, and analyze the very ideas that led to these histories getting buried. One of these ideas, as I see it, is paradise.

It is not possible to bury the past without traces remaining aboveground, in the present.

I suppose there is no place on Earth that could not definitionally be called paradise—no place that is not, in explicit or implicit terms, a walled enclosure of sorts. The word itself is a curtain stretched thin over time, expanding unintelligibly, obscuring a truth that lies buried beyond.

History, too, is a curtain, dark and thick. A curtain we stretch across uncomfortable truths.

Paradise Extended, where my great-grandfather Henry is buried, now summons to my mind the almost-laughable image of Paradise undergoing renovations. Walls knocked down and flooring cut, construction crews overseeing—all for a new addition. A larger, more capacious Paradise suitable for a growing family of inhabitants. In other words, Paradise Extended brings attention to the fact that “paradise” is a word under construction. It calls to mind what the palimpsest illustrates—that we can cross out and add on extended meanings of the word through time. Paradise is a palimpsest: a landscape on which we are constantly rewriting new cultural meanings atop the old; shadowed yet still visible.

Palimpsest

The poet Charles Wright writes in his book Black Zodiac:

Memory is a cemetery

I’ve visited once or twice, white ubiquitous and the set-aside

Everywhere under foot …1

I am unsure why that day at Lindenwood remains so clear in my memory even now. I feel a strange and overwhelming urge to return to Lindenwood Cemetery—to be the one to chisel a stone, to vandalize the garden’s cruel dominion. I am “in search of lost time,” like Proust’s narrator, who was dragged into memory by a madeleine and Tilia blossom tea—tea derived, I discover, from flowers of the linden tree. I think that if I can only carve Henry’s name, I can write my history. It is all we can do to recall the forgotten dead.

That I feel so strongly about a name etched onto a grave—chiseled into stone—is, if anything, only evidence of my own bias for writing. It is a bias toward literature, toward language, a written record. To write is to memorialize. The self, the world, an era’s preoccupations. It is a means of endowing people’s lives with words that will live beyond them.

To write into history is to know a palimpsest intimately. It is to reconcile the notion that parts of the record have been written atop others. To discern where our cultural record has been rewritten and obscured. Most of my ancestral narratives have been written over by others—forced out of history’s borders. To write into my history is to become familiar with the cruel landscape of a particular American palimpsest, to struggle with and against it.

Now, almost a decade later, I type Henry’s name and his birth and death years into the Find a Grave online database, ashamed to hope that we were wrong all those years ago and that his name has been archived in stone all this time. The error message mocks me: a red exclamation point punctuated with the message “No matches found.” This notion reinforces the larger tragedy in the search for my ancestors: that what I hope to find of them is nowhere. What lives in my imagination is not in reality matched. The names they wore, the legacy they left, were no match for history’s discriminating slate. The search for knowledge of my predecessors has largely turned up blanks; their story remains highly debatable, an unmarked stone I try in vain again and again to read.

Morrison writes in her novel Paradise:

But can’t you even imagine what it must feel like to have a true home? I don’t mean heaven. I mean a real earthly home. Not some fortress you bought and built up and have to keep everybody locked in or out.… Not some place you went to and invaded and slaughtered people to get. Not some place you claimed, snatched because you got the guns. Not some place you stole from the people living there, but your own home, where if you go back past your great-great-grandparents, past theirs, and theirs, past the whole of Western history … back when God said Good! Good!—there, right there where you know your own people were born and lived and died.

Home is discoverable only when we abandon paradise.

I am writing from Lindenwood Cemetery, where I am standing for the first time since my first visit almost a decade ago.

It is summer: a brutally hot day. The shadows play across the graves, same as they have for over a century. In my hand I hold a map of the cemetery on which section 14 is highlighted in fluorescent yellow, a false beacon. Below, the dead wave me on in silence. I don’t wander. I don’t spend an hour searching the rows of marble and granite, as I once did.

This time I know where I am going—where to find my story.

- Excerpt from “Meditation on Form and Measure” from Oblivion Banjo: The Poetry of Charles Wright, by Charles Wright. Copyright © 2019 by Charles Wright. Used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Poem originally published in the volume Black Zodiac.