Widening Circles

An Interview with Joanna Macy

Joanna Macy, Ph.D., is an eco-philosopher and a scholar of Buddhism, general systems theory, and deep ecology. As the founder and root teacher of the Work That Reconnects, Joanna has created frameworks for personal and social change, transforming despair and apathy into constructive change. She has written numerous books, including Widening Circles, her personal memoir, and World as Lover, World as Self: Courage for Global Justice and Ecological Renewal. Joanna is widely known for her translations of Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker and a Sufi teacher. His films include: Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, The Atomic Tree, Counter Mapping, Marie’s Dictionary, and Elemental. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, and New York Times Op-Docs. He is the founder and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

Ben Suliteanu is an aspiring filmmaker specializing in editing and sound design. He recently graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in science, technology, and society.

In this interview, Buddhist eco-philosopher and author Joanna Macy discusses her life and work. From her anti-nuclear activism in the late 60’s to her work with deep ecology, Joanna expresses the need to live within an ethic of care for the earth.

Transcript

Joanna MacyI would like to begin with just centering a minute—

Emergence MagazineOf course.

JM—and a grateful prayer. Beloved mother, father, lover, earth, our larger self, our greater body, we’re so grateful to be granted a human life right now at this time of such anguish, turmoil, and so much suffering and loss is occurring; and we’re so grateful to be given human identity and a human voice and so we can take part in human councils. And help us to be evermore fully aware of the blessings of being part of your intelligence. So be it. Okay.

EMWell, I wanted to ask you a question about your youth, because I heard you talk about how you had some very impactful nature, mystical experiences when you were on your grandfather’s farm in upstate New York. And I was really curious in the context of this discussion of how your relationship with earth has changed and deepened over time and how it has influenced your work and the many ways that you have brought forth the conversations and connections to earth over, I guess, fifty years of work in so many different ways and spheres—that first moment of having a connection to earth and recognizing something alive there and what those experiences were like for you.

JMI was nine when I started going for the summers to my grandfather’s farm. It was in western New York a couple of miles north of the Erie Canal. And it was very simple: no indoor plumbing in the first years, a horse-drawn plow, a few pigs, a dozen cows, chickens, horses, and so forth. So it was the same time I’d been taken to live in New York City, and I hated it: the noise, the grit, living high in an apartment. We didn’t have a car, so we would just wait till school was out and go up for the summer. And that journey up from Grand Central on the Empire Express by train to Buffalo—eight hours—was like approaching the Pearly Gates, getting out of prison. So the quiet of it, the soil of it—There was quite a bit of boredom for a girl my age, which I now think was just fine, because I would wander a lot. And I was given a horse for my care. He was excused from his draft duties of drawing, and I was allowed to ride and take care of him. And images from that time—the way the stream would come down through around a bend and all the little crawdads in it—still comes to me; or wandering into a corner of a stand of the woods and seeing one of our horses disappear into it. This is like the stuff of my neural assemblies in my brain: just where the sun would be across summer as it moved south, as it set. I felt I was open to there having been a lot of time, and my people going back, and my world filled with brother/sister beings of kittens and dogs and the calf we were growing.

With every passing year, I am more grateful for that time. And when I wrote my memoir, I began it right then. I began the memoir with a sense of who and what I am that I received sitting in my favorite place to be: in the maple tree. And it was never more than a third of the year at the very most—usually just a quarter of the year—that was intense enough to give me imagery and a heart connection, a felt resonance, an emotional resonance, that has been a touchstone for me for . . . let’s see, for the following, let’s see—I’m almost eighty years older than the nine-year-old that came for the first time.

EMAnd how did these experiences, this notion of kind of kinship or friendship or aliveness that you felt, how did that interface with your Christian upbringing and kind of the notions of God and relationships or—

JMQuite well, because, you see, we were a family of quite liberal Protestants; so I loved the hymns of St. Francis, and I loved the sense of belonging. But there was, just about the time I left the farm, the dichotomies in religion between flesh and spirit, and people who were extra Ecclesiam nulla salus, no salvation out of the church. And not that I heard that much, but I was so in love with the sacred that I decided to study theology and scriptures; and that’s when the problems started for me, and I finally, by the time I was graduating from college, had to walk out of the church.

EMAnd at that time, how did that affect your relationship with nature, this beginning of—

JMWell, nature was what was left.

EMAnd was this when you were in—

JMAfter leaving college.

EMSo you were in France at this time?

JMYeah, in my young adulthood and in my marriage with my husband. He took me into the natural world farther than I’d ever been. And we were camping and canoeing, and I was out in the mountains, and I was skiing. And so there was a tremendous sense of exaltation with the beauty of that. We barely talked, and we were two of the most talkative people with each other. Once we were together, we talked a blue streak, but not camping. It was just like being in a cathedral, you know. You don’t burst into conversation in a cathedral.

EMAnd was this in the mid-’60s at the time?

JMWell, I married in the early ’50s, ’53, yeah.

EMSo, this was before you did your work with the Peace Corps?

JMThat’s right.

EMBecause I was struck in learning about your experience there with the Tibetan refugees, and it seemed like it was the right time at the right place after the right set of experiences that had opened up something in you that allowed you to be present to that experience, at least from my perspective looking outside.

JMI know, it’s extraordinary how fortunate I was with that unfolding.

EMAnd, I guess at that point you had not found a spiritual or religious path outside of your experiences in nature that had touched you and silenced you and your husband in that great cathedral.

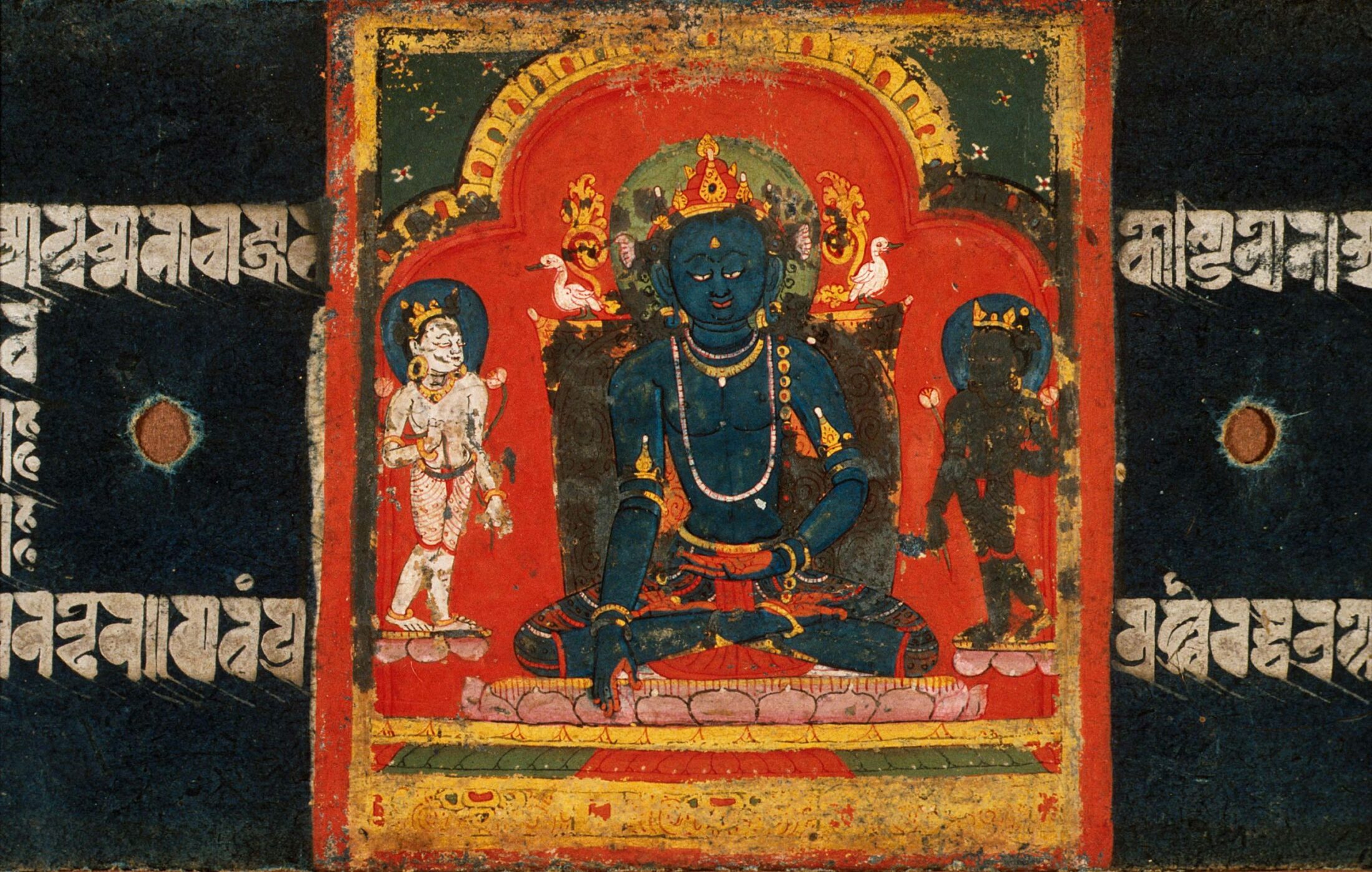

JMIt was this quality of their presence in the world. I just had never met people like that. And here they’d come out, sick, exhausted, with just the clothes on their back and the sacred objects they carried out over—through periods of snow-blindness—over the mountains. But their quality of being in the world was seeing everything as if for the first time. And, I don’t even know if I knew those words; but when I walked on that Losar, Tibetan New Year’s, morning across the tea estate where they were squatting, these eastern Tibetans, and I heard the long horns for their morning puja and saw the tall flag poles with the cloth rippling, and there was just, oh . . . yes. . . I’m worthy to be given this.

EMAnd this was after your antinuclear work?

JMYeah.

EMBut your antinuclear work seemed to have a very influential role in your life, and this concept of time that emerged from that.

JMYes. I was gripped by a summons, through my son’s freshman term paper. It was when he came home from his freshman year at Tufts, Environmental Engineering, and he handed me—he said, “Mom, you might be interested in seeing this paper I wrote.” And, I said, “Well, I’m sure that I’d love to read it.” And then when I did, it changed my life, because it was about the pollution from nuclear reactors—not even the radioactive, just the thermal pollution that was changing the waterways and coastal waters. Every reactor needs so much flow through of water, and it contaminates every spoonful of it.

I found it so horrific. And so before the end of the year, I had joined him in his affinity group protesting the Seabrook construction, the Seabrook reactor, in New Hampshire. And then it just tumbled. I was just learning so much.

EMHow you shared that story in the past is—there was something in you which felt compelled to act in a way maybe you hadn’t before.

JMYeah, that’s right. There was no question. What bothered me was, I was discovering all this information of how the Virginia Electric Power Company [was] racking their spent fuel rods too close together. It was illegal and it risked a critical action, an explosion. And, so, I went to join them, and I did it simply ‘cause I’d gotten so discouraged. I’d had a kind of—fallen into a moral abyss of questioning whether human life, even complex lifeforms, could continue, that we were so stupid. I wasn’t clinically depressed, but despairing—

EMBut you were feeling what was overwhelming about this particular issue.

JMYeah. But fortunately I got very interested in why people were able to turn away from wanting to even talk about the dangers we face. I was getting a lot of information, but people didn’t want to hear it when I’d bring it up at a meeting or a dinner party. People didn’t say, Oh, I’m so glad you brought up nuclear power. And so I thought, Why are we avoiding what we need to know? What is it? And, I began to read psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton and his work around—he named “psychic numbing.” He had done a study of the effects of nuclear bombing on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And then he found that the same thing was true of the people who made the bomb. And we too were not wanting to look at it. And then I found there are a lot of things we don’t want to look at. We don’t want to look at the statistics about birth defects and miscarriages around nuclear installations. So, that led me into experimenting—Why do we not want to know this? And is it because it’s not patriotic? Is it because we think we’re crazy? Is it because we’re afraid of moral pain? What is it? And, that curiosity was like a little fishhook that pulled me out of the horrific despair. So I began to experiment—because I was also teaching meditation and using that—Could people, how do people, react to mental and moral pain? Or, how can they talk about what’s hard to feel? And so that was incredibly revealing to me. And out of that I built a form of group work that led to where I am today.

EMWith the grief work? This was the beginning of the grief work?

JMSo we called it despair work. And then I wrote an article about it. But then this article, which was how to deal with despair, generated hundreds of letters, more than had ever come into the journal. And although I didn’t tell people—I just said how we dealt, when I found what despair really was. It was a form of profound caring, which was good news about us; and not to be afraid of it; and the ways to live with it; and how you can turn it into action. Every single person—Nobody said, you didn’t tell us how to solve all our problems or anything, or even one . . . but thank you. They said, thank you, thank you, for showing me I’m not crazy.

EMMmm.

JMAnd so then I was invited to do workshops on this article, and I said, well, I don’t—

EMYou wanted to be a university professor.

JMYeah.

EMBut life was pulling you in another direction.

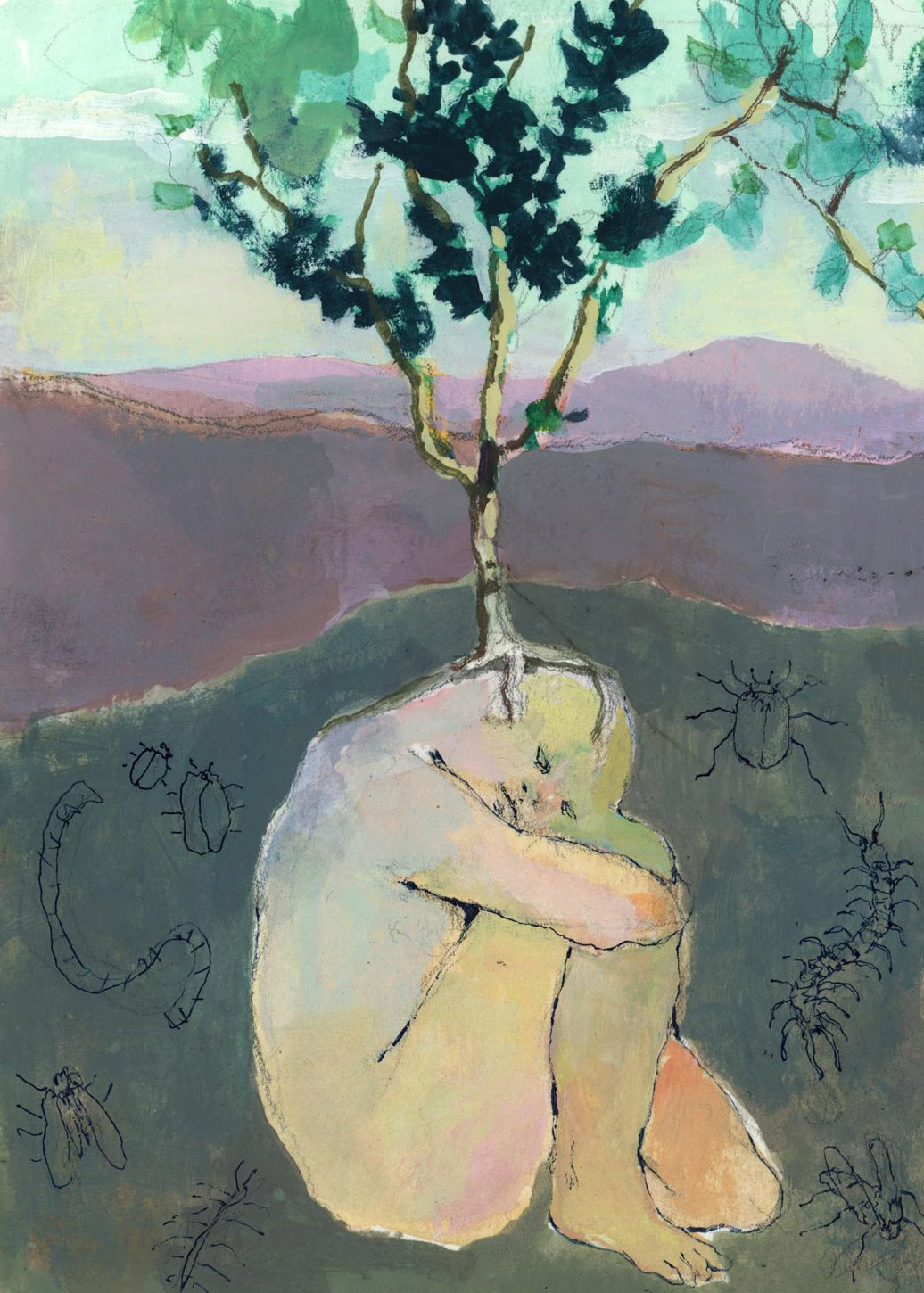

JMYeah. And this caught on very fast, and there were people joining me. It was really—I was inviting them to explore and express their despair, their outrage, their grief, their fear, their dread. And there was a lot, because this was in the Cold War still, and Ronald Reagan was being elected, and there was the nuclear arms race. And—I’d never seen so much hilarity, this just, ah, such liberation and—Because we were reframing. We weren’t pathologizing our grief and despair, which is what the dominant culture does with the help of the pharmaceutical industry. So, this is normal. It’s constructive. But then what I noticed—they began talking as if they’d had a shift in identity from being a separate individual to being the earth. Often, it wasn’t jokingly, but—you could feel it, that they had an expansion of sense of their own autonomy and personal relevance. And so I thought, “Well, this certainly demonstrates paticca–samuppada,” which was the Buddhist term for our interdependence, our interexistence, our interbeing. Boy, that is demonstrated, and I didn’t even expect it! But then I heard the term “deep ecology” and the term that belonged with [it], the “ecological self”: that when we mature, a natural maturation of the human is toward widening fields of relevance and caring, and that your self-interest expands from being just what affects you inside your bag of skin to what expands your family or tribe or country to what happens to earth. And I saw that. I said, Oh, people are—we’re experiencing that—Also, not only the “ecological self” but in Buddhism there’s the term the “bodhisattva”—as the individual with boundless heart, who won’t even step into and take rest in nirvana until every blade of grass is enlightened, so all beings are freed from suffering.

EMI mean it sounds like that was a convergence in your life of these different experiences you had: the Buddhism teachings that you had been studying and practicing for, I guess at that point, almost twenty years; the deep time work experience of being aware of the impacts of the nuclear energy systems that were being developed; the grief that you had experienced—and then coming together in a powerful moment. What did that do to you, personally, when you felt those worlds converging?

JMWell, a lot of words—joy, humility, gratitude. I guess gratitude most of all. And the—Circumstantially, in our planetary journey, things are a lot scarier and a lot more destructive now. But I still hold, since those last—what’s that, thirty years since that “deep ecology” word became—I was giving a name to what I had already been experiencing; because I didn’t plan it. Here was this—I called it a shift in identity. People were acting as if they were more than their separate self, but not in any kind of controlling, self-flaunting way, but humbly. And my feeling is, whatever happens—and this gives me ballast, Emmanuel. It gives me a sense that—I have a lot of grief for what we’re doing to our world and to the future. But I know at the same time that whatever happens, I won’t—there’s nothing that can happen that will ever separate me from the living body of earth. Nothing. It’s who we are, and that is so vast. My mind is just able to experience that much of what is there to experience and to open to. I’m still too small in my imaginative and intellectual power to be able to really take in what that means. But the little that I have offered tremendous comfort. Nothing can ever remove me from the living body of earth, whatever happens, or all of us. So we’re already home.

EMThat work has been very powerful for so many people these last thirty years, who’ve, I think, felt what you were describing too: the power of that larger perspective and way of being in relationship. And yet, as you said, times are difficult. And even today we’re sitting on probably one of the hottest days on record in the Bay Area in October, and fires have been burning in the North Bay.

JMAnd I’m aware that what kind of comfort—you know, I could see somebody up in Santa Rosa say, “What kind of comfort is that? I’ve just had everything I ever had burned to a crisp. I’m left with nothing.” And I felt the fear of that myself last night after the huge winds and the heat. I feel such awe that at this very time that we’re landing ourselves in such a pickle as humans on this planet, or as life on this planet, that there’ve been two great rivers in the human journey, spirituality and science—and in our early days, they were interwoven, but they’ve been hideously separated over the last centuries, and we’ve been torn apart by that—and now, in our time, they’re flowing together, and the promise of that is huge. In every major religion there’re these voices, but it’s coming so strong from the indigenous ones—[saying] that the earth is alive, and the earth is sacred. That follows, because if the earth is all we have, then we’re totally dependent on [it], and then that is sacred to us; and [it follows] that we wake up in this time to the sacred that we’re living within and nourished by, the sacred living body of earth and its intelligence, her/his intelligence. And not only that, but I feel that in this time, the dangers we face are creating a huge evolutionary pressure on us to wake up to our true nature. We gotta wake up to that or we’re toast, bigtime.

EMYou’ve had a rich, to say the least, life and experiences that led you one after another to deepen this exploration, deepen this journey, deepen this conversation with the earth, and awaken something in you which prompted you to awaken something in others. And your work has done that in so many ways for thirty years. But I’m always left with this question now is that—because I too feel this emergent possibility and the crying out of the earth to be recognized again and to be heard and to be listened to. But I also wonder how people can learn to listen again. Sometimes it can take a lifetime to learn to listen. I guess the big question is, how do we learn to listen if we don’t have the time to go on a journey like you have or go into the work that you have offered to so many in a deep way? But what are the ways we can learn to listen?

JMWhat a wonderful way to begin, in a way, because that’s the question: How do we learn to listen? I feel—I sense a hunger and thirst in people to be present, and I—there’s no question in my mind that our presence in our world is the greatest gift we can give it. Curiosity is a beautiful path, and we can walk the path of how we listen and how we help each other listen. Sometimes I see the path we’re on as having a ditch on either side that we could fall into; and one is paralysis, just shut down in fear, and the other is panic, social hysteria, turn on each other. And learning to listen a little, for either one, calls you back.

EMSo there’s a book sitting to your left that you’ve had here since we’ve been sitting here talking together and—

JMOh, can I give you what I thought of some lines? You could put them in a little box.

EMWhatever we can do I think would be lovely, but I have a question for you before you read.

JMYeah?

EMIt seems like your relationship to Rilke has been a huge part of your life.

JMOh, yeah. And it’s been so—yeah, and actually, when I first encountered his poetry was back in the ’50s, very soon after I’d walked away from Christianity. I was in Germany. My second child had just been born, the same one who wrote later about nuclear reactors. And it was a snowy day, and I go into a bookstore near the university, and there’s this little—Oh, I have it here. I think I have the very—Ah, da ist der doch! Das Stunden-Buch. That’s the very book with the old gothic script.

EMThis is the book you found in the bookstore in the ’50s? And this is a book that in some way changed your life?

JMYeah.

EMAnd so, what happened when you opened these pages?

JMI picked it up, and I opened it, and it fell open to the second poem: “Ich lebe mein Leben in wachsenden Ringen/ die sich über die Dinge ziehn.”

I live my life in widening circles

that reach out across the world.

I may never complete this last one,

but I give myself to it.

I circle around God, that primordial tower.

I’ve been circling for thousands of years

and I still don’t know: am I a falcon,

a storm, or a great song?

I had thought that I’d failed on my spiritual path. I thought my spiritual path was a linear one, that it would go like Pilgrim’s Progress through various stages of learning to the heavenly city. [But] to “live my life in widening circles”? I said, “Oh! I can own that.”

We’re so lucky to be alive now aren’t we?

EMWe are indeed.

JMAt this moment, where anything we’ve ever known how to love, and everything we’ve ever learned—how to seek courage and connection—can serve.