The Other House

Open storyObserving the grief that has arisen during the coronavirus pandemic, poet Jake Skeets explores apocalypse, time, and futurity from a Diné perspective.

Musings on the Diné Perspective of Time, Memory, and Land

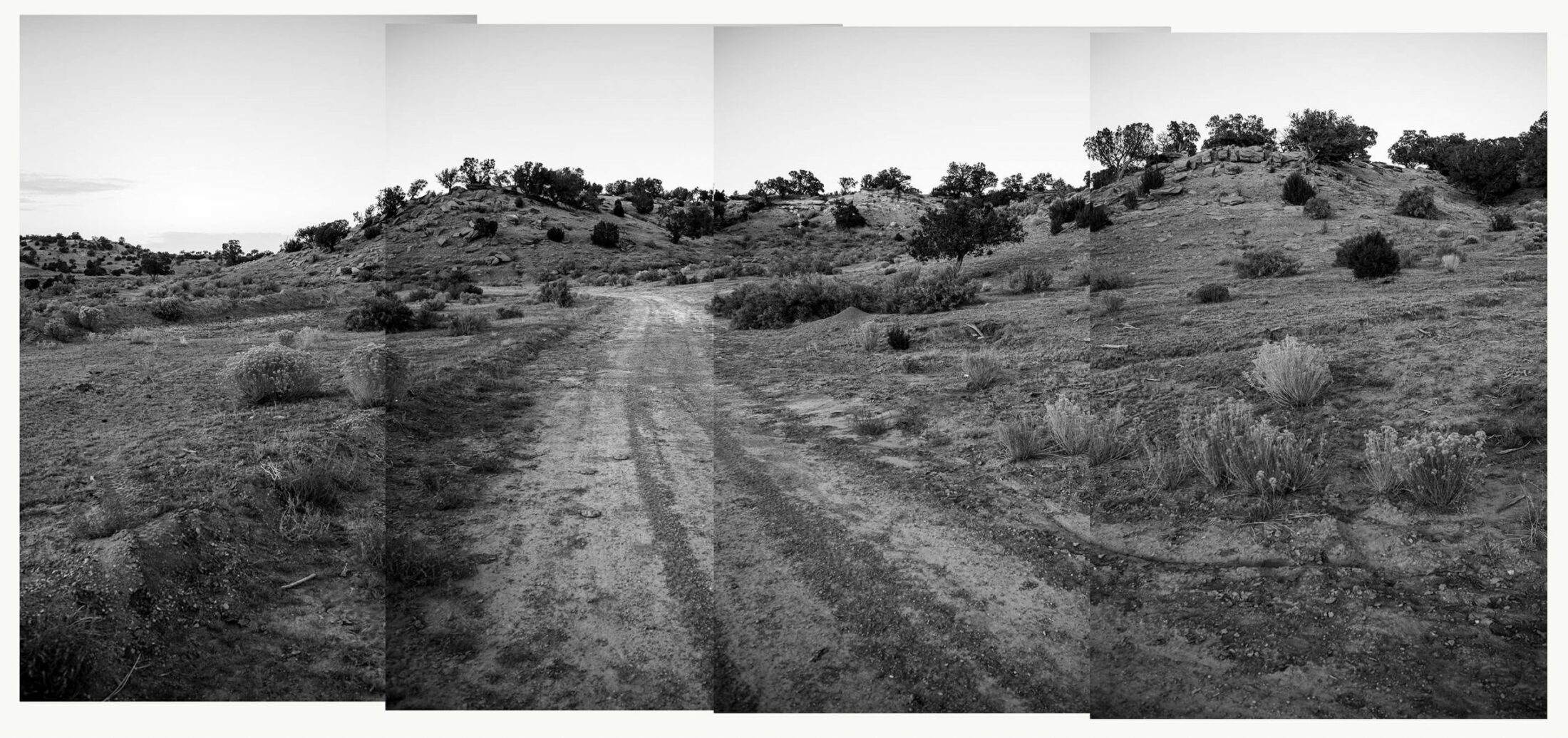

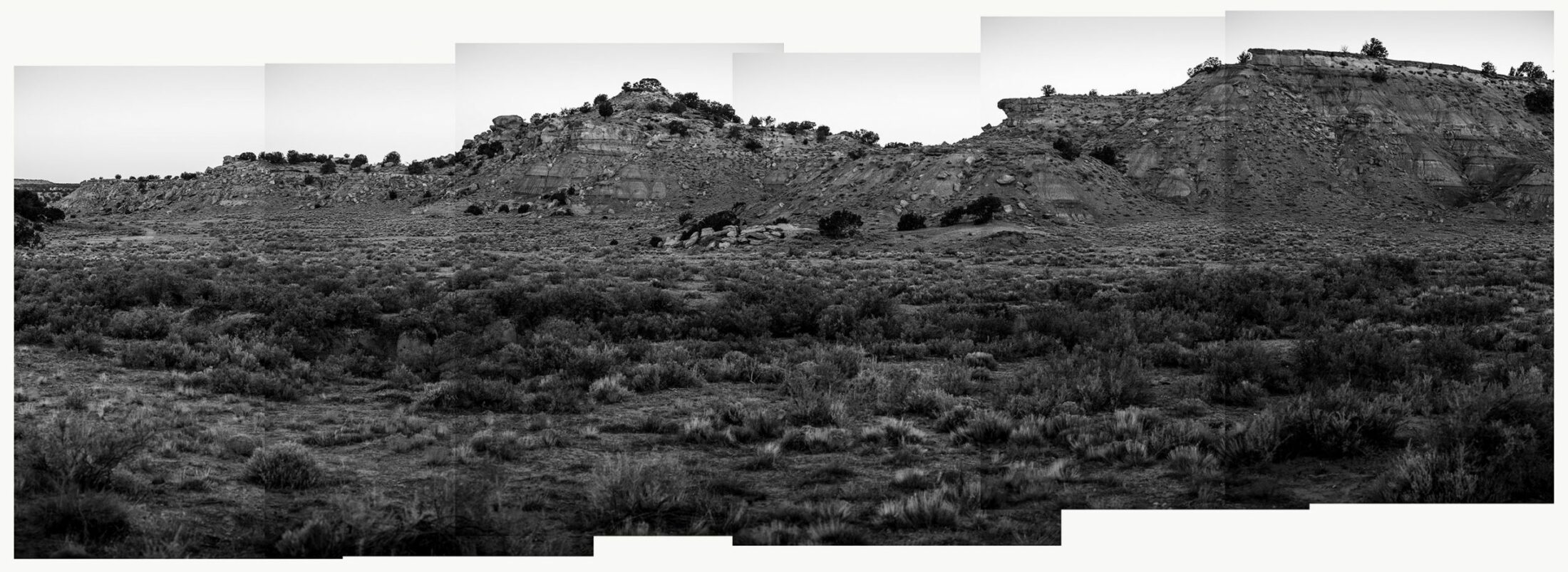

Photos by Bear Guerra

Jake Skeets is Black Streak Wood, born for Water’s Edge. He is Diné from Vanderwagen, New Mexico. His debut collection of poetry, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, was a winner of the National Poetry Series and the American Book Award. He won the 2018 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Contest and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His honors include a 2020–2021 Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellowship and the 2023–2024 Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi. His research explores Diné poetics and aesthetics, ecopoetics, Indigenous queer theories, and critical Indigenous feminisms. He currently teaches at the University of Oklahoma.

Bear Guerra is a photographer whose work explores the human impact of globalization, development, and social and environmental justice issues, often in communities typically underrepresented in the media. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Le Monde, BBC, and NPR, and has been exhibited widely. He was a finalist for a National Magazine Award in Photojournalism. Bear and his wife, Ruxandra Guidi, work together under the name Fonografia Collective to produce local and international print, radio, and multimedia stories about human rights and social justice. Bear is also a board member and producer with the award-winning nonprofit journalism collaborative, Homelands Productions, and is the visuals editor at High Country News.

Recalling visceral moments in his life, poet Jake Skeets explores how time and land hold “fields” of memory that can unfold through language and storytelling.

Memory is a touchy thing, and I mean that in the realest sense. The earliest memory I have is of my hand feeling the chin stubble of an older man. The room is evening-lit. My hand reaches out, and I graze the chin’s prickly skin. The older man smiles. I can’t see his entire face. I don’t recognize the house we are in, but it feels like a small home. I see the color red, but I don’t know what in the room is red. Maybe it’s the man’s jacket, made of a shiny fabric with a red band across the back and chest. I hear no sound, taste no thing, and I smell no distinct aroma. I can only feel the rugged chin and my hand gliding across it. Then, the smile of the man.

It won’t be until after returning home from college that I learn the older man is actually my maternal grandfather. I was in the car with my family, and my mother was telling me the same story she has told me a thousand times: When I was an infant, my maternal grandmother would tie me to my high chair and spoon feed me. She also used to tie me to her chest and walk to the sheep corral to care for the goats. This time, however, she told me a new story. She told me I used to reach out to my grandfather’s chin, wanting to feel his stubble. I told her then that I remember an instance of doing that: my hand and his chin stubble. My mother nearly broke into tears. My maternal grandparents passed when I was still very young; I should have no recollection of them. Somehow, I remember that one moment between me and my grandfather.

In another early memory, I always see in the third person. I see myself coming out of my aunt’s house. This moment tends to replay itself at random times. I can clearly make out the darkness of my eyes, my hair somehow a lighter brown than it is now, and my face scowling. I have a bowl cut, one of the many my father gave us when our hair grew too long during the summer. I stand there looking out toward my other aunt’s house. I have on a blue T-shirt, and I remember having just eaten, because I feel full. I have this moment stained inside me: I’m looking outward and mad for some reason. I know it’s late afternoon because the house casts a large shadow in the front yard that makes it cool enough to linger outside. I don’t know much else about this moment, or why it’s somehow repeated in the machinery of my mind. I also don’t know why I see myself in the third person. Who is the I looking back at my former self? Is it my present self? Or was it my past self that etched that moment into my memory? I have repeatedly dissected this moment, trying to identify any real reason as to why it exists. The only thing that stands out to me from this memory is how dark my eyes are in the shade and the rough feeling of my aunt’s house when I trace my finger along its outer wall.

Memory fields: pond by the windmill, lime green skin, my cousin’s fish tank, the sheep corral, dark soil, dark coffee.

One time, my brothers and I swam in a small pond by the windmill that came and went with the rain. Each monsoon, the pond would swell and buzz with a thousand tadpoles. The water was always cool. Suddenly, my youngest brother screeched in horror as he lifted his hand from the murk, clutching a green lizard-like creature. It was long like a snake and had gill-like ears protruding from the side of its head. Its skin was lime-green and shockingly clean. It squirmed to be free of my brother’s clenched fist. We ran from the water and onto the crusted surface dirt, careful not to excite the creature.

What had we caught? Was it a salamander, a newt, or a Loch Ness Monster pup sent here from across the world by harsh winds, dust storms, and ribboned rains? In my memory, that’s what we asked. In my memory, we carefully extracted the creature from the pond and placed it into a glass pickle jar that we found in the rubble near the windmill until we got home. Once home, we filled the glass pickle jar with sink water so we could study the animal. Inside the jar, the animal magnified into a large beast as we watched its eyes dart back and forth. That night we kept the beast at my house. The next day my oldest cousin came by and picked the beast up to put it into his larger fish tank. I watched him fill the tank with tub water; a fine aquarium dust settled at the bottom. I remember sitting in his room while my cousins all played Nintendo and studying the beast as it danced in the tank, glowing and free. Its legs were dress-like: they flowed beneath its body, swirling around the tank in radiant glimmers. In a few days’ time, the beast was dead. I never knew its name.

One time, my aunt came over in a panic. A huge storm passed through; I could see the black mud layered on my aunt’s shoes as she barged into the house. Her face was wet and her eyeglasses were foggy. She explained that a lot of her goats were dead from a lightning strike. More of my aunts came over as the dark outside seemed darker than ever. I saw faint glimmers of lightning in the east as a cool wind calmed the storm down. My mom asked me to make coffee as everybody opened cookies and yeast bread to share. My aunts sat around the dining table sharing stories. Every now and then, they would transition back to discussing the task at hand: building a new sheep corral. After a few plans were made, they would venture off again into another time when this thing happened, or that one time that one relative did that one thing in town. They managed to travel through time without effort, in loud bursts of laughter and quiet sighs.

I remember putting a big pot of black coffee on the table. My aunt smiled and told me she liked my coffee best because of how strong I made it. Then, she dumped spoonfuls of powder creamer and sugar into her cup until the coffee turned beige. My aunt then gestured toward her cup, telling me with just body language to taste it. I picked up the cup and tasted the bittersweetness. I almost spit the coffee out and everyone laughed at my unwillingness to swallow it. I washed down the taste with some soda from the fridge and went to my room. I remember thinking about the sheep corral and the dead goats left there. I could smell the dark soil; the coffee tasted like it.

I am always fascinated by the idea that the starlight we see today is in fact old light cast out from a time existing simultaneously in the past, present, and future.

Memory is a physical construction. While memory is normally associated with the cognitive functions of the brain, I argue that memory’s connection to time imposes its existence onto physical space as much as it does onto cognitive space. I am always fascinated by the idea that the starlight we see today is in fact old light cast out from a time existing simultaneously in the past, present, and future. The star’s light began in its present, a past to us when we see it in our present, which is the star’s future. I first learned this in seventh grade science class. Astronomy and the periodic table stood out to me during those years. This course was my sixth-period class out of seven for the entire day. During the course, I would develop intense headaches, making it hard for me to concentrate. One day, I remember panicking because I couldn’t see the periodic table on the chalkboard anymore. I told my parents and they took me to an eye doctor. I had inherited the hazy vision of my parents and a rather intense form of astigmatism.

I remember, on the day I returned to class with my new glasses, we had a lesson on the optical systems that give our eyes the ability to see color. Light reflected off of objects creates the color we see, thanks to the technologies of our eyes. My teacher asked me to hand him my glasses to show the class. He explained that the need for prescription glasses is related to the ways eyes interact with light. Why he chose my glasses is beyond me—he, too, wore glasses. But I remember that particular moment: my seventh grade teacher holding my glasses up before the class, as I watched the afternoon light shine through the lenses. Today, whenever I see sunlight shine through lenses or glass, I am reminded of that moment in that classroom when I learned that, because sunlight takes 8 minutes and 20 seconds to reach the earth, the things we see are in some way a part of the past. Pasts, presents, and futures exist simultaneously.

There is a pond near my family’s sheep corral. Whenever I see or remember the pond, I am reminded of many moments of my childhood, my past. The pond is a physical construction of my memory, much like sunlight passing through lenses is. It’s a memory field. The pond itself is small and sits at the entrance to the sheep corral. The pond also sits at the entrance to my childhood. It holds the moment my cousin stood in the pond with her overalls rolled up and dozens of tadpoles swimming around her ankles. She wore light and faded overalls with a stark-white shirt. Her hair was held back with a headband and flowed out in deep, dark curls. She covered her face with her hands as she squirmed at the touch of the tadpoles on her feet. Her clothes were new, and we both shuddered when we heard her father yell her name. We both knew the kind of trouble she would be in. I remember her slowly walking out of the pond, her head down. She left footprints in the dark mud between us. I looked down and lifted my right foot slowly in an attempt to catch tadpoles on the top part of my foot. A few of them slid off as I lifted my foot out of the brown water. I heard yelling as the door shut behind my cousin. I didn’t mean to get her in trouble. As I sit here typing this moment of my past, the visceral experience of the moment is pulled from the past into the present (my child-self’s future), and I feel these moments again. I feel the tadpoles swimming around my feet and the wind cooing as I watch my cousin walk toward her house. I sit back in my chair and think about the stories conjured from this pond, this physical and cognitive space.

Memory exists as a kind of spatiotemporal entity, because time, memory, and land are woven together. One cannot look at the Grand Canyon without conjuring the deep time needed to create it. We drive past restaurants, and maybe we remember that one time that thing happened. I grow weary of the word “spatial,” because I am more interested in the idea of a terrestrial-temporal matrix. I call this terra-temporal matrix the “memory field” because of memory’s unique engagement with time and land. Time is terrestial and feeds our cognitive development and relationship to the universe itself. The word “terrestrial” also grows heavy; it has similarities with words like “sublunary,” which place the terrestrial opposite a religious or spiritual space. The word “temporal” isn’t adequate either. The memory field is a matrix of time, memory, and land. Land’s connection to time feeds our development as human beings, and understanding this connection strengthens our relationship to the universe itself.

I talk often about the way energy conjured from landscapes finds its way into my poetry. Both the ponds near the sheep corral and the windmill enjoy an existence within my being as temporal, physical, and memory tools. Throughout our lifetimes, we develop many memory fields as we navigate humanhood in ever-changing times and environments. As we venture in and out of these fields, we are essentially participating in time and space travel. The act of remembering is a technology of the cognitive and physical parts of the human body. Radical remembering is the ability to travel through time, space, and existence. Radical remembering is connected to storytelling, which is an act of survivance for various Indigenous communities across the world. Radical remembering is a tool we hold deep within each of us that can help shape our lives, communities, and Nations. The memory field is the key to radical remembering.

In his book Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination, Mark Rifkin argues that Native people exist in a timeless space, everchanging between referential frames of time. Native people exist in a “precontact” past or within a “postcolonial” current, depending on which American consciousness and gaze are being employed. Native people are given the ability to transcend physical limitations of representation—they walk from spectacle to activist to spiritual to contemporary to dead. However, it is through memory that Native people reclaim a history both individual and collective, both personal and communal, both deeply intimate and extremely political. Memory is woven in a unique matrix with land, language, and time. Native people have already mastered time travel: they are able to conjure the deepest parts of humanhood through the act of memory. Radical remembering, then, has the potential to teach a way of being that isn’t tied to a capitalist future but is instead reliant on the self’s engagement with the natural world. I don’t mean that we should return to precontact Native life, but we should push forward into a new realm of thinking about memory, time, and land. I can’t provide an example of what this looks like, because there are no examples to pull from that exist in our physical reality. Instead, I turn to language and storytelling because of their connection to our memory fields.

As we venture in and out of these fields, we are essentially participating in time and space travel.

Rifkin refers to the concept of simultaneity, which I’ve discussed before when addressing my own work within poetry. Chiastic structure in verse opens spatiotemporal reasoning within language. Within Standard American English (SAE), a sentence’s syntax should be subject-verb-object: for example, “I am going to the store.” Within Diné syntax, the sentence becomes “The store is where I’m going to.” In fact, this sentence comes from Luci Tapahonso’s poem “Hills Brothers Coffee.” Within SAE, the subject is placed at the center and verbs into the world. Within Diné syntax, the spatial reasoning of the object is centered and therefore ignited within the reader’s mind before the speaker and verb. In another example, “hello” is considered a standard greeting in SAE. “Hello” has a mixed past and is considered to be drawn upon “hallo” or “hollo,” which are words said to attract attention. However, according to a brisk Google search, “hello” is first referenced within the American West as a normal welcome when entering a house. One would utter “Hello, the house” upon entering a home to announce themselves a friendly neighbor and not a savage Indian. Again, the subject verbs into the space. This space is then closed off from the frontier. The American home is immediately placed opposite the savage wilderness. Within Diné universe, “yá’át’ééh” is considered a standard greeting. However, yá’át’ééh has a much deeper translation that acknowledges the surroundings of the speaker and those around the speaker. Its loose English translation is “from the sky to the ground and everything in between we are here and it is meant to be this way.” Yá’át’ééh acknowledges the landscape and offers back to the universe a sense of balance. This is needed now more than ever.

Memory Fields Pond, gill, reptilian green leather slick in brown hands A finger tracing a stucco wall a stubbled chin Blood rivering from the knees Like lightning striking a sheep corral A thousand tadpoles, looking like rain rattling the water

The memory field reveals a spatiotemporal existence through the acknowledgement of and engagement with time’s physical self and the spatial contexts of that existence. When I introduce myself in Diné, I start first with my mother’s clan. I’ve learned that it’s also appropriate to identify where your mother’s family is from both physically and historically. That is, one should always try to learn their family clan’s stories and history. Then, I share my father’s clan, my maternal grandfather’s clan, and my paternal grandfather’s clan. Again, you should always try to mention the homelands of these families and clans. This insight into the world and ways of introduction centers land and stories. Spatial contexts are centered in almost all ways of being within the Diné universe. There is order, and that order comes from a deep reverence for space. This spatial reverence is something I channel when I approach poetry on the page.

Poetry has a deep connection with the idea of memory field. For me, a blank page becomes an altar where the memory field is teased into existence. The field of the page becomes a kind of physio-textual landscape, and it’s the poet’s job to render a blank page into a literal field using language. The job of the poet is to apply spatial reverence both within the field of the page and the physical constructions beyond the poem. I think of Diné weavers and the symbolism behind a loom. Diné weavers use organic materials found within nature to weave together a story, a memory field. The warp symbolizes rain, so Diné weavers are literally weaving time, memory, and land onto a rainstorm. Diné weaving holds an extreme reverence for the memory field. I argue that poetry should be no different. Poetry should have reverence for its land and landscapes. I’m not arguing that poetry should come with a land acknowledgement. Instead, I am arguing that the field of the page should do what the land does for us on a daily basis. One way to accomplish this feat is through radical remembering.

When one makes their way over the Chuska Mountains through Buffalo Pass—from Tsaile, Arizona, to Shiprock, New Mexico—they are met with the startling sight of Shiprock just over the summit point. The mountain sightline transitions into pink and orange sand stretched for miles in a flat plane of terrestrial glamour. Suddenly, the structure of Shiprock erupts from the surrounding flatness. There are many stories associated with Shiprock, and each time I make my way down I am reminded of those stories. I won’t share them here of course but each time we pass Shiprock a story accompanies the geological phenomena. Shiprock, a holder of memories, becomes a memory field too. Each time we pass through these roads my partner will mention a rock formation’s name and explain the story behind its naming. He’ll ask, “Do you know why they call those rocks that?” Then, as we drive either to or from the Chuskas, he will tell another story, and sometimes it’s the same story about the rock formation and its name. Within the lexicon of Diné universe, Shiprock and similar images of snow, arroyos, and rock formations deal with the past, present, and future, because each comes with a story. If I were to name a few random images, such as reeds, knob, rainbow, corn pollen, virga, mesa, horse trough, chapter house, Burger King, and Lotaburger, Diné readers would each begin to travel through time and space into these memory fields, populating them and existing simultaneously in the past, present, and future.

For me, a blank page becomes an altar where the memory field is teased into existence.

Memory is a touchy thing, in that you can touch it. I often rub the scarring on my knees from when I jumped off a swing during the summer lunch program at Bread Springs Day School. My brothers, cousins, and I were swinging, and I jumped and landed knee first onto the side railing of the sandbox. I hopped up and looked at my leg; rivers of blood were gushing from both of my knees. I ran to the restroom to stop the bleeding. I remember thinking that if the cooks or caretakers saw me bleeding they would not let me go with the group into town. This summer lunch program would pick us up at our homes for a free breakfast meal. After, they would let us into the playground with giant swings and a really fast merry-go-round. Then, they would take us into town to watch a free summer movie at the theater or play at Ford Canyon Park. They would take us back to the school for a free lunch in the afternoon. After we finished, they would take us back to our homes. Today, I think about the blood gushing from my knees and my worry that I would be caught and punished for bleeding in the first place. That memory is literally scarred into my body; I am unable to forget it.

In a way, I am arguing for the recategorizing of land through radical remembering and the memory field. Today, we are faced with an onslaught of new challenges as wildfires seep into cities, hurricanes grow in the seas, and big freezes take entire communities by surprise. The American colonial project that marked much of the land as a wild frontier has led to this very moment. Through radical remembering we are able to reclaim these wilds and frontiers as intimate parts of our very being. In that way, wilds and frontiers are transformed into homes and fields. They become part of the domestic, the intimate, and the spiritual. By reclaiming memory as a thing we can touch, we give a body to the memory machine that exists inside of our minds. It is this body that tells us stories. This body, our body, tells us stories. And sometimes our body listens for us to tell the stories of ponds, windmills, downtown buildings, apartment kitchens, dining tables, and tadpoles. We remember them and continue to remember them.

Memory fields: ______, ______, ______, ______,

Observing the grief that has arisen during the coronavirus pandemic, poet Jake Skeets explores apocalypse, time, and futurity from a Diné perspective.