Speaking the Anthropocene

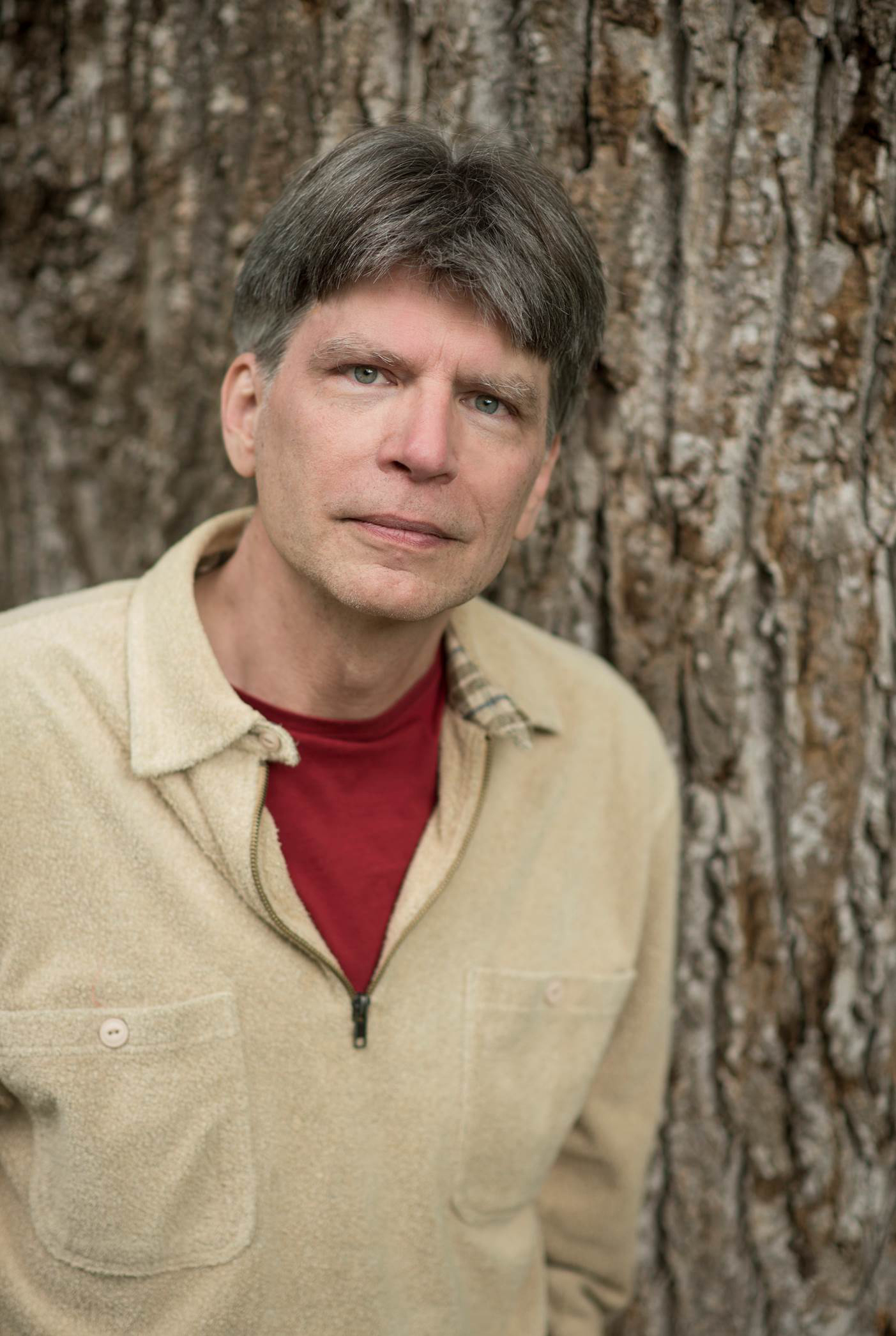

Robert Macfarlane is the author of books on nature, place, and people, including Underland: A Deep Time Journey; The Lost Words (with Jackie Morris); The Old Ways; The Wild Places; Mountains of the Mind; Landmarks; and most recently, Is a River Alive? His work has been widely adapted for film, television, music, dance, and stage, and translated into many languages. Robert won the 2017 E.M. Forster Award for Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Granta, and The Guardian. He is a core member of the MOTH (More Than Human) Life Collective and wrote the lyrics for “Song of the Cedars.” He lives in Cambridge, England, where he is a Fellow of the University of Cambridge.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this in-depth interview, writer Robert Macfarlane articulates the consequence, the responsibility, as well as the pleasure of naming the living world.

Transcript

Emergence MagazineIt’s a pleasure to be speaking with you today, and getting a chance to explore your work, and this ongoing journey of the language of place that you have been developing for many years. My first question is where this comes from inside of you, because so much of your work focuses on this relationship, the place, and the connection to the landscapes, forests, waterways, pathways, and other natural spaces in your home in the United Kingdom. And it almost feels as if you’re developing or sharing a language of place, a way of using words that creates a real intimacy for the reader with that place, even if you’re thousands of miles away, like I am today. And I think one of the reasons it’s so effective—and maybe this is my assumption—is that I feel your connection and your relationship and your love of these places and these landscapes so vividly. It comes through very strongly. So, I’m curious to learn a bit about your journey and how you became so drawn both to the landscapes and places you write about, and specifically to the language of place.

Robert MacfarlaneWell, language and landscape are the two braids that have twined and untwined in my life, and in my writing to this point. I teach in a literature department, but really, I think I’m a bit more of a geographer these days. And I have been fascinated by how language is both our tightest limit—our event horizon when it comes to apprehending and approximating to the landscapes in which we live and the nature with which we share our lives, broadly speaking—but also the extraordinary possibility and opportunity it holds.

There’s a paradox at the heart of all of this, which is that, of course, language is not, in our sense of it, a natural capacity. I think I write somewhere in Landmarks that granite has no grammar. Light does not use syntax. Robins do not speak in syllables as we would recognize them. And so, language is always late for its subject in nature. I’m fascinated by language’s affordance when it comes to thinking about and shaping our relations with place and what we might uneasily call nature; I’m also interested in the binds that it places us within.

EMI get a sense you’ve spent a lot of time in the spaces you write about. Was this something you always had an affinity for—the natural environments of Great Britain—or is this something that was learned over time?

RMWell, I love listening to people. I love talking, as I know you do, but even more I love listening. It’s long been my habit to travel to landscapes that fascinate me and to talk to people who know them very well, profoundly well, whether that be through work, through science, through art, through poetry, or just through long, everyday acquaintance. And these subtleties of relation that emerge through chronic contact, through chronic relationships with places—cities as well as moorlands—they fascinate me. So, I’ve always asked questions of people who live in places.

But poetry has been a huge force and presence in my life. The three poets who I met earliest were the three H’s. They were Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, and Gerard Manley Hopkins; and in a way, for that troika of poets, words have a kind of palp and a heft that is as strong as a pebble or a gale. And I was fascinated by writers who fought and sought to give to their language aspects of matter, and who sought to give to matter aspects of language.

EMAnd was it being in these spaces that initially—because I know you have a background in mountaineering, and you spend a lot of time out there in the cold, in high altitude environments—was it being in these places, or the places that you journey to on your way to the peak, that prompted you to seek out these poets as a way of understanding what you were feeling?

RMThat’s a fascinating question. In some ways, being in high mountains in a storm or at real altitude is an experience that sort of batters language into uselessness. In many ways, you fall back on practicalities, on tool use, on rope skills, on navigation, and language isn’t much use to you—it doesn’t get much grip up there in the high mountains. And I love that really. Quite often on the summit of a mountain I just say, “Wow.” It’s not a loquacious response to the view laid out before me. But mountains—they live in deep time. They occupy phases and scopes of place and time that make a mockery of language.

So, yes, in one sense, a long, long acquaintance with mountains as a walker, as a mountaineer, and as a reader made me aware of how useless language is in its relations with place. But it did also make me look for a language of purchase and attention. For example, Gaelic—Scottish-Gaelic as opposed to Irish-Gaelic, though the two are closely related—has this fabulously refined lexis for mountains. I mean, there are thirty to forty words for the top of a mountain alone, and each one slightly distinguishes between the kind of peak. A sgùrr is generally a sharp peak, and a stob also tends to be quite an abrupt peak. Other words discriminate between tops that have corries beneath them, or tops that are longer, have ridges running off them that might look like beinn cruach and have a long summit ridge. When one looks closely, one finds that there are languages of fine discrimination at work not only in our cities or our technologies—where, of course, such languages proliferate—but in our landscapes as well.

EMThat brings us to the work that you took on for your book Landmarks, which in many ways is a celebration of the power words hold through their specificity, as you just described. In reading the book, you feel there’s a certain magic that comes across between the landscapes and the people who develop those specific ways of describing those landscapes—terms that, as you said, “enchant our relations with nature.” And in the book, you compile glossaries of words from all over Great Britain that capture that certain magical intimacy with the natural world, words that in many cases are now rarely spoken, or are losing relevancy, or in some cases even being lost. And when I was rereading some of those words, I was again struck by that specificity and how the loss of these words is yet another example of how we’ve simplified and homogenized these incredibly expressive and rich ways of describing the world around us, and often instead replaced them, and put them into broad categories. You talk about how there’s so many words for meadow or field or stream or mountaintop, but instead we have these broad categories, which everything is supposed to fit into. I’m really curious to hear what your perspective is on what you think is lost when that specificity is gone.

RMIt’s a really good question. I think the important first answer is that there’s an ethical and a political dimension to what is lost when specificity is lost, which is that landscapes that are generically apprehended and generically described are more vulnerable to misuse, however we define that. And an example of that might be—I write in the first chapter of that book about the Moorland of Lewis, which is one of the Northern Outer Hebridean Islands. And “moor” is self-similar. That’s what it does. There’s moor, and there’s moor, and there’s “more moor,” as the old joke goes over here. And if your perceptions are not inclined to apprehend the detail of moorland—its ecologic complexities, the extraordinary work it does in terms of carbon storage, the community home it provides for invertebrates, as well as migrating birds, and the astonishing colorscape and cultural ecology that it very often encodes and makes possible—then you look across a moor and you see a generic space, a waste space; a wild place if you want to call it that, which is to say somewhere that can be used or converted, because it is of no use as it stands. And I’ve always been interested in community resistance to large corporate misprisions of places.

The Isle of Lewis is a complex scenario, but what Europe said at the time was that the largest onshore wind farm was due to be effectively planted on the Lewis moorland, and these were going to be gigantic turbines, which would occupy the entirety of the inner moor of this sizeable island. And there are very good reasons why we need onshore wind turbines and renewable energy, but this was not an appropriate development. But for the developers, it became important to mobilize the idea of this landscape as self-similar, as generic, and therefore as waste/disposable. And similar conflicts have been happening in Sheffield in Britain recently, where a large-scale PFI (private finance initiative) contract is committed to felling thousands of street trees. And again, the battle came to be over: what’s the use of these trees? To the contract, as it were—to capitalism in its rawest, most hungry form—the trees were merely street furniture that was undesirable. But to the inhabitants, to the local community who put together this extraordinary campaign of resistance over nearly two years, which has met remarkable success in the courts and in the hearts of people, these trees were profoundly subtle. And it came down to a battle over description. It seems to me, for these reasons, when we decide what we’re doing with infrastructure, and when we decide what we’re doing with our less modified landscapes, precision of utterance and a kind of grammar of reciprocity and registration is profoundly important.

EMAnd, of course, what happens when wonder is removed from those landscapes by simplifying and changing the way we describe them? I want to share a quote of yours that really struck me: “The right names well used can act as portals into the more-than-human world of bird, animal, tree, and insect. Good names open onto mystery, grow knowledge, and summon wonder. And wonder is an essential survival skill for the Anthropocene.” I love that quote, and it seems to be so important, because, as you describe, people care about these trees. But imagine how much more they would care about those trees if they knew every single way of describing them, like the ways of describing trees that you list in Landmarks.

RMLook, there is bad naming. Let’s be absolutely clear about this. Naming is an ethically neutral act until it’s directed, and there’s all sorts of bad naming. The Trump Administration knows very well the power of naming to direct, and disguise, and control attention and possibility within bureaucracy. A lot of work has been done by many groups and many individuals, including Rebecca Solnit, on the forms of renaming that the Trump Administration is undertaking. So, there’s definitely such a thing as bad naming; but there is good naming too. And that good naming might be political, it might be the refusal to describe the natural world as “the environment,” which I don’t do any longer. I find that to be a problematically chilly and alienating term. I tend to use the phrase “living world” or “natural world,” and not to talk about “climate change” but to talk about “climate breakdown.” These are small acts of renaming, which have considerable political encodings and consequences. And then, at a kind of gentler level, there are, it seems to me, these wonderful histories and othernesses that are opened into and onto by forms of common naming, shared naming. An example of that might be the dandelion, which is often dismissed as a weed, often mowed here in the UK. It flowers first in March. It’s a really important species for early emerging pollinators, bees coming out drowsy and needing a good feed. They land on red nettles, and they land on celandines, and they land on dandelions. Dandelion comes from dent de lion in French, meaning “tooth of the lion” or “teeth of the lion”; and that’s a reference to the serrated edge of its leaves. There’s already a wonderful vividness to that name. The dandelion has dozens, scores of other common names, each of which refers to an aspect of its involvement in human culture and human perception. One of them is pissenlit, which means “piss the bed,” because dandelions have a diuretic property. But others—son of the grass, fallen star of the football field—they speak of a kind of fun-ness and a familiarity. These, to me, are examples of good, gentle naming.

EMMmm. I love that. Another thing that really struck me in what you present in Landmarks is this idea that the words assembled in your book are a possibility of how we can re-wild our contemporary language for landscape. You described that as being the hope, so to speak. But this raised a question for me, which is, do you think this is possible when so much of the wildness that inspired the words that you assembled no longer exists, or is so drastically different?

RMHmm. Yeah, it’s a really good question. So, this idea of re-wilding—by which I mean this rich regeneration of place, of possibility, of hope, a thriving of diversity as opposed to monoculture—this is a cultural as well as an ecological project, it seems to me, and it’s one that celebrates diversity. And that’s why when I tried to gather this word hoard, as I call it—which is phrased from Beowulf, from the early literature, the early poetry of these islands—I didn’t want it to be the word hoard of one language, English, which is itself anyway a mongrel global tongue. I wanted to delve into the many languages and dialects and subdialects and new apprehensions of place that are underway. I think there are thirty-three or thirty-five languages, dialects, and sub-dialects represented in the glossaries of Landmarks, and they range from Scottish-Gaelic, Cornish—which comes from the Brittonic language groups—and through to English regional terms that are different as soon as you cross a county boundary or a river.

There’s a lovely word, smout, which means the hole in the bottom of a stone wall up in Cambria, which is left so that small creatures can move through it but sheep can’t get out. And that sounds lovely, benevolent, a little bit of vernacular architecture; but actually it’s also a means of trapping that food. So, the people would often dig little pitfall traps at smout holes in stone walls so that a rabbit would come through the smout hole and drop into the trap for the parts, but these days they don’t tend to be trapped; whereas, if you go down to Sussex, you’ll find that a hole in the base of a hedgerow left by the movement of an animal is called a smeuse. And that word has been a really good example of how what looks like an archaic term is actually still alive, and also has this huge vivifying power for the eye. This word smeuse is a kind of keyword in the book, and it’s taken as an example of how learning a word sharpens the eye and changes the vision. And I’ve had so many letters and emails from people saying, “Gosh, since I’ve known that word, I just see those little holes that creatures make everywhere, in the fences, in the hedgerows,” and that’s both a sort of trivial recreational perceptual act, but it’s also a tuning into the amazing density of commutes and convivial life, more-than-human life, that we share our landscapes with. But that generally goes unregarded, unvalued, and unaccommodated.

EMBut, at the same time, those words that you’re describing were developed at a time where it seems like there was more time spent in those spaces, and now we’re in a time when most people are not in those spaces, or they’re there for recreation purposes, or they’re there because they’re farming or they’re living a rural existence. It’s so different than it was before. This is something that I think about a lot, which is that as we adjust to this change, this incredible change that we’re dealing with—of loss of landscape in so many ways, loss of diversity and loss of a living, vibrant system that supports us—how are we going to describe that? And how are we going to develop—as we all are creatures of story, we all are creatures of language—how are we going to express that in a language of loss, so to speak? And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that here we are in this incredible renaissance of nature writing, of environmental filmmaking, of incredible art being created all over the world that is a response to this—of trying to grapple with and develop this language.

RMAbsolutely right. And I think always at this time of a line from Brecht. Brecht says, “Will there be singing in the dark times? Yes, there will be singing about the dark times.” And I think this great choir, this multi-voiced, poly-vocal, diverse set of songs is being lifted and raised at the moment. Some of them are angry. Some of them are plangent. Some of them are hopeful and future-oriented. Very few of them are sort of leisured and lazy. I think the sense of loss has become hugely animating to the discourse. And it’s animating politics too. I’m speaking to you on the day of yet another climate strike by young people, and they’re in Cambridge now. They were there—I was with them a month ago with my daughter and my six-year-old son, who is absolutely mesmerized and horrified by climate change and what it connotes and what it connotes to him as loss. I think this idea that loss as an experience is always a sort of inter-passive, elegiac mode is wrong now. I think it is an energizing mode, politically and culturally.

I would also say that this ugly world of making that we are bringing into being that we call the Anthropocene and the Chthulucene, the Capitalocene—these many names that we’re stuttering out for this epoch that we’re making—is calling this sort of second order of lexis into being. And that order of lexis is another kind of neologizing. It’s the neologizing for microplastics, nurdles, mermaid’s tears, these attempts to get hold of the mess we’re making. Plastiglomerates is this ugly, hard to speak, hard to swallow word for a new possible horizon market substance in the Anthropocene, and stratigraphy is what happens when you melt down coagulates of plastics—having a campfire on a beach in Hawaii—and gradually, the melting plastic picks up the sand and the organic matter and the other kinds of debris and the bird feathers, and then sets and forms this odd new hybrid substance that geologists have called plastiglomerate. Well, you know, we’re always making new stuff. And as we make new stuff, of course, we make new language for it. I’m fascinated by our attempts to speak the Anthropocene, to speak geo-traumatics, to speak solastalgia.

EMBut do you think that’s actually a way of honoring and really grieving, or is it just a response of survival, of trying to find the names to describe the craziness?

RMWell, without wanting to turn into an essentialist, I think we are a naming species. Some of the oldest stories in world culture are the stories of name giving. And so, I think you’re right to find it the beginnings of a response. I think it is a means of pointing, denoting, comprehending. That is the sort of first-level predecessor to reaction. An example of that might be Glenn Albrecht’s influential term “solastalgia,” which I’ve already mentioned once, which he coined after working with communities whose landscapes were being profoundly disrupted by drought in Australia, long-term Anthropogenically-induced drought, and by big corporate mining endeavors in these small communities in Australia. And he realized that what these people were experiencing was the loss of their landscape without ever leaving it. The landscape was changing around them due to these huge forces. They were living in a new place without ever having moved. And he said, “Well, this isn’t nostalgia. We need a new word for it. Solastalgia was the coinage he came up with. And, again, the response to that word now, over fifteen to twenty years—if you Google it, you’ll find so many think pieces and essays around it. It’s fascinating to me. Suddenly people think, “Ah, yes, that’s what’s happening.” The campaigners in Sheffield recognized it as what was happening to them. They lived in a hugely forested city, a city with a canopy. Suddenly, the canopy was being cut. They were experiencing solastalgia. The urban forest in which they lived was becoming thinned and felled, and that was part of their response. So, again, maybe that’s an example of how a kind of ugly language for the Anthropocene isn’t just descriptive, discursive. It’s active.

EMPerhaps that’s a good segue into listening to some samples of what has been created by this wonderful group of artists and musicians who were inspired to create sonifications of some of the words and phrases that you include in Landmarks. And the project, which is slated for release in a few months, is being headed by Andrew Tasselmyer of Hotel Neon, who has kindly shared some of those tracks from the album with us to listen to today. I think we’ve got three tracks today, and I’ll let you explain the tracks, and the words, and what they mean.1

RMThis amazing project just came out of the blue to me, and this extraordinary ensemble of field recorders, musicians, sonifiers, who have gathered from around the world and around cultural traditions. The first one we’re going to hear is Benoit Pioulard’s response to a very specific Gaelic phrase from the Isle of Lewis, which is a two-word phrase, rionnach maoim. Apologies to any fluent Gaelic speakers out there who may be regretting my pronunciation of it. It literally means mackerel moor, but it’s used as a phrase to compress down and register the shadows that are cast by clouds on moorland on a sunny, windy day. It’s a phenomenon of weather, of perception. It’s born of labor in place, in different kinds of weather. It’s a wonderful metaphor that transfers the mottled patterns of a mackerel’s flank—which is one of the fish that would have formed the main diet in that area—onto the moorland itself. And it’s also astonishingly compressive. It compresses an atmosphere and a complex phenomenon down into a few syllables. This is Benoit’s musical response to it. <music plays>

EMWhen I’m listening to that track, I actually feel like I’m both lying on a moor looking up at clouds over my head, and then also looking at shadows. You know, I think it really does a quite remarkable job of taking you into a sonic experience of dimensionality. It’s quite remarkable.

RMThat’s brilliantly put. Yeah, absolutely. The dimensionality, I think, is what really sets that apart. John Constable has a lovely verb. In one of his journal entries, I think, he talks about skying, and that meant lying on his back and studying clouds. Obviously, he’s one of our great artists of light and weather and cloud, particularly. This feels like a track about skying. But, as you say, it’s not just looking up. It’s also that open, fleeting movement of light across open ground. There’s a wonderful line from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem where he says, “Glory be to God for dappled things.” And this seemed, again, a celebration of dappled-ness, of diversity, and movement, and shift.

EMWell, yeah, and also the fact that this is telling a story, and the story is grounded in the phrase that it’s come from, which tells a story too. You know, the moving shadows cast by clouds on moorland on a sunny, windy day. I mean, that’s a story. And if you said, “cloud moving,” it’s not a story—it’s an explanation of an action without any of that subtlety in poetry and lyricism that is the human relationship with the landscape. It’s remarkable. So, should we listen to another track?

RMYeah. This is by Hotel Neon, which is one of Andrew Tasselmyer’s bands, or projects. And this is titled “Rime,” or this responds to the word “rime,” and that’s not the rhyme in the poetic sense. That’s rime, R-I-M-E. I love rime. I have a long relationship with rime. Rime is a kind of ice, or a frost, if you prefer. And you will recognize it if you see a photograph of it. It’s that extraordinary, feathered ice that grows in very cold, windy conditions. And it forms these amazing, kind of boas of plumage on mountaintops, boulders, trig points, whatever it comes into contact with. What is fascinating to me particularly—and metaphoric and suggestive—about rime is that, counterintuitively, it grows into the wind. So, you look at rime ice, you see its feathers, and you assume that they’ve been blown by the prevailing wind outwards. In fact, rime leans into the direction of the wind, because it’s caused by supercooled water droplets brought by that wind, freezing instantly on contact with a cold surface, the existing surface of the ice. So actually, when you see rime, it grows into the wind. It gives you that direction. For me, metaphorically, as somebody who has already gone to the mountains and found myself in some way grown by them, rime is the ice of my heart, as it were. So, here is “Rime.” <music plays>

EMThat’s another beautiful, beautiful track. I really feel both the beauty and the joy, but also there’s a little bit of danger there and coldness, and it’s a bit dramatic.

RMIt is, and I think it catches that sense of gale and cold, as you say, but for me, also, that idea of rime growing by enrichment, by contact, by building on itself. And I think when you have that architectural notion of something that leans into the arduous in order to grow, I think the music is doing something very clever there in the way that it grows out of itself and into what is coming at it.

EMHmm. And what’s the origin of rime? Where in the UK is it from?

RMYeah, it’s …

EMWhat language group?

RMIt’s a Norse word, actually—rema. Rema is the Norse origin of this, and so it comes in as part of the Viking legacy here; and Gaelic itself, and Scots, and of course English, have internalized many, many, many Norse words. There are all sorts of interesting finities that register this Atlantic arc of cultural consequence and trading and relation that actually is, in a way, far, far more consequential linguistically than the continental, the southern continental, axis.

EMRema. We’ve got one more track we’re going to listen to, which kind of segues into your latest book, Underland, and this is called “The Tunnel,” by Richard Skelton, who is recording as “The Inward Circles.” Could you give us a little background about the tunnels and what inspired Richard to take this on?

RMYes. Richard Skelton is one of the most extraordinary musicians, writers, poets, cultural presences in Britain at the moment, and I would urge listeners to seek out Corbel Stone Press and the work he does with Autumn Richardson, who’s a musician as well as a writer. I wrote a chapter about Richard in Landmarks, which is called “Underland,” and it describes a journey we took under a raven’s nest into some old mine workings, and we passed through what felt like a gateway space: two big portal stones, a big yew tree—holly tree, rather—growing above this entrance to these mine workings in the Northwest Lake District. And we followed this tunnel until its collapse point. And there we sat, and we felt this extraordinary breathing. We were holding candles, which was our only light, and the flame of the candle would lean towards the collapsed roof of this tunnel and then would be kind of exhaled and would lean back towards us, then would lean in again, almost sucked in by the breath of the mountain. It was a very powerful experience of a sense of a lively earth, and I think Richard’s track, “The Tunnel,” comes in part out of that time we spent together and what I wrote about it subsequently. <music plays>

EMWhen I listen to that track, it’s very, very different to me than the previous two. I really do feel like I am now belowground and there’s something pushing down on top of me. And it’s got a darker quality to it too—not just in the fact that maybe light is not above you, but also maybe you’re looking down into the depths of something.

RMHmm. That’s a great description of it. Those big, bass drones that are just burrowing away under there, hollowing things out, deepening things. That reverberant space, and also for me that sense of rock as lively, given time—as breathing, as animate within deep time. I think it’s a fabulous piece that stands, as you say, in wonderful contrast to the openness and the light of “Rime” and of “Rionnach Maoim.”

EMWas this journey with Richard that you undertook while writing Landmarks kind of a precursor to what you ended up exploring in your latest book, or was that already underway? Was Underland underway?

RMWas Underland underway? Underland was underway, and Underland has really been underway since—the very earliest signs were 2010, that extraordinary summer, when the Icelandic volcano erupted, when the Chilean miners were trapped in the gold and copper mine in the Atacama Desert, the San Jose mine, and also when the Deepwater Horizon blowout occurred.

That all happened in one spring and summer, April to August, and that was a summer when you couldn’t not think of the underland and what was beneath us, rising up to us or taking down from us. And so I think the book Underland had its first origins there. And then it’s taken so long to write and to think. It’s a big book; it’s 500 pages. It’s really the last decade of Anthropocene thinking, and thinking about language and place and journeys into darkness that we have made.

EMYou described it as the longest, strangest, deepest, darkest book you’ve ever written and probably ever will write.

RMYeah, that’s about right, I think. It’s taken a lot out of me, and in terms of language that’s partly because I realized very late that what I was writing about was what might be called obscenity. That which is obscene is that which we do not wish to speak. It’s that which we do not even wish to see. We wish to keep it “off scene,” and that’s tended to be what we do with darkness in the underland. It’s where we’ve put the things that are too dangerous to us to keep on the surface. Nuclear waste might be a material example of that, but also ghosts. The dead, the feared dead. But it’s also where we’ve put the things that we love so much that we want to keep them safe from the surface; and that, of course, includes the bodies of those we love. One of the early chapters of the book considers the earliest known cemetery in Britain, which is in a cave in the Mendips called Aveline’s Hole, where 10,000 years ago these undernourished, challenged, early hunter-gatherers nevertheless took their dead and interred them over the course of around a century, moving the stone across the door and back again to keep the animals out. There is a tenderness of burial that was at work in that practice that fascinated me.

EMI guess there’s a very different kind of place-based language that exists beneath the surface.

RMHmm. There is, and in a way it’s one that we don’t disclose to ourselves. If we think about the ways in which underworlds and underlands figure in story and in myth and in culture, they tend to be trauma, grief, the unconscious, the undermined. This is the place of half-seen things and part-articulated utterance. So, finding a language for this very often inhuman realm, a realm of matter before it is a realm of people, predominantly, was—yeah, it took time. It took a long time.

EMWell, we’re featuring one of the chapters in Underland in this issue of the magazine. The chapter’s called “Understory,” and it takes you on a journey into Epping Forest in London with a plant scientist named Merlin Sheldrake. And in the chapter you explore the implications of what some are calling the Wood Wide Web, this subterranean network of tree–fungus mutualism that was discovered by the forest ecologist Suzanne Simard, revealing not only how trees communicate with each other but also how they care for each other. There is a social network of sorts between trees, and as Simard beautifully describes, there are beautiful structures and finely adapted languages of the forest network. In the chapter, you write about how our current way of using language to describe this nonhuman language falls short, and that perhaps we need an entirely new language system to talk about fungi. We need to speak in spores, as you say. It seems to me like you’re talking about a language that is animate, that is alive.

RMYeah. Well, wouldn’t that be nice. Well, where to begin with that? The first thing I’d say is that this extraordinary sort of yield of the underland—this mutualism, fungi-tree mutualism, the mycorrhizal network—has been probably in existence for around 450 million years. We’ve really begun to see it in the last twenty, and this is a great example of the way the underland keeps secrets from us. It’s the most surprising realm, really.

The second thing to say is that since it’s been disclosed by Simard and others increasingly and popularized, we’ve tried to make sense of it. Of course we do—that’s what we do. But the kingdom of fungi is so other, is so extraordinary and unlike us and makes such a nonsense of our categories, that we end up doing what we always do, which is sort of converting this structure to our own metaphors and our own understandings.

I became interested in how there are two broad movements to interpret the Wood Wide Web. One is the one you’ve already implicitly endorsed, which is a sort of socialist vision of the Wood Wide Web as enabling trees to care for one another, share resources, distribute wellness, as it were, too. So, if a tree is sick, it will be given to by healthy trees. This is sort of a National Health Service as well as a Wood Wide Web going on there. And the other is the opposite. The other is the near-liberal account. The Wood Wide Web is just a facilitator for an aggressive marketeering, free marketeering forest, where it just means that trees can kind of compete with one another better and in more interesting ways. And obviously, both of these are projections; both of them are implicit in the poetics of the science that is used to interpret and represent and explore this phenomenon. But they are human projections. And so when I was walking this forest with this extraordinary man, Merlin, he conjured it all open for me and really rendered the ground transparent for me. I, and he, both came to feel a frustration with this automatic move that we make to anthropomorphize. Even when we think we are doing pure science, as it were—there is no such thing. So, how do we talk about it? Well, of course we don’t have the language for it, but maybe—and here we loop perhaps back to our early discussion about Landmarks—perhaps we need a language that is alert to reciprocity, alert to forms of vivacity in the more-than-human world that our conventional language forms do not register.

I’m interested in grammar as well as single words. Grammar is, if you like, language’s underland. It’s where meaning sediments over long periods of time and becomes ideology, effectively. Single words are obviously actions; they’re choices made on the surface. They have deep histories, they have roots, in that sense—but grammar is the sedimented version of many forms of choice made by cultures and individuals over many years. If we think of grammar as having an underland—well, the underland of our grammar, of English as I understand it to be conventionally used, is not one that recognizes the more-than-human world with richness, respect, reciprocity, and legitimacy.

EMI’d like to talk to you a little bit about Lost Words, and this is your recent collaboration with artist Jackie Morris; and it’s a beautiful book. Some call it a children’s book. I think that’s not the case. I think adults should be reading it. And it has an incredible quality of bringing you into the physicality of the book itself, which I love, because it’s this huge, large book. I mean, it takes over your whole lap when you’re reading it.

And you can’t quite hold it up. You need to sit it on your lap or a big table, and then you’re engulfed in it; and it includes poems or spells, as you described them, paired with Jackie’s remarkable paintings of words that have been removed from the Junior Oxford English Dictionary. I wonder if you could talk about the genesis of this project?

RMYeah. The Oxford Junior Dictionary is one of the various dictionaries available to primary school–age children in this country: so probably five-to-seven-year-olds, six-to-eight-year-olds. Very, very widely used. And in the 2007 edition, it was noticed by a sharp-eyed reader that—it has about 2,000 words in it, this dictionary, so it’s very limited, necessarily—but it was noticed that these words had been taken out. The words were acorn, bluebell, catkin, conquer, willow, wren, heron—these very common names for common nature, or in some cases, decreasingly common nature. Skylark and starling are having a really hard time in this country right now. It wasn’t the dictionary’s fault. I always say, if I hadn’t been a writer, I would’ve liked to have become a stratigrapher, lichenologist, or lexicographer. And I think lexicographers are awesome, and dictionaries are generally descriptive rather than prescriptive. They tell us how language is being used; and what this dictionary told us was that language, these words, were not being used by children or for children as much as they had been. So they made way for other words, and those words included attachment, block-graph, committee, broadband, voicemail, and so on. It was a pinch point, a kind of symptom of this tech/nature faceoff, which is itself a false opposition; but it became hugely animating to conversations around nature, childhood, and so forth in this country—sometimes in an alarmist way, and sometimes in what has become a very creative and productive way. So, Jackie contacted me and said she wanted to make what she called a beautiful protest about this idea of childhood and nature and language and schism-ing.

EMHow did you choose the words that had been removed? Because there were quite a few more than what ended up in the book.

RMYeah, there were about forty “nature” words. I wanted to make a sort of A-to-Zed. There was no Zed, because we don’t have zebras in this country, but I got from acorn to wren. We took twenty words, and for each word I wrote a spell, a summoning spell, to be spoken aloud by parent or by child or whoever read it; and we’ve been astonished by who has read it. Jackie would paint first the object’s absence: an absence of acorn is a field without trees in it. Then she would paint an icon on gold leaf: the acorn on its own, set fabulously against gold leaf, like an icon—a religious icon, Orthodox Christian. And then she would paint the object, the being, back in the landscape, full of the ecosystem, fully in the ecosystem, of which it was part and which it creates: an oak tree with its butterflies and its moths and its owls and its leaves and the shade it gives. It was a thought experiment, a kind of magical thinking, about what might happen if you could summon back into the mouth what also should be summoned back into the landscape.

EMSo that’s why you call them spells, because it’s really an invocation to remember and reconnect back with these birds or plants or creatures.

RMExactly. The other sense of spell is the prosaic one. I took the first letter of each word and used those to begin the stanzas. Each spell is itself a spelling out of A-C-O-R-N for acorn or H-E-R-O-N for heron; and when the children are reading it, they have fun finding these letters and spelling them together to make the word, then speaking the spell, and so it goes.

We released this kind of strange, wild creature of a book into the world in October 2017, and I remember that Simon McBurney, the great actor, was one of the first people ever to see a copy, and he held it up just so. He said, “This isn’t a book; it’s a landscape,” as he sort of disappeared headfirst into it. And I thought, “Ah, wow. That’s interesting.” It has lived a truly wild life, this book—continues to astonish me every day.

EMTell me a little bit about its impact, because it’s quite remarkable what’s happened since the book has been released, and how it’s kind of taken on a life of its own.

RMYeah. Well, in very simple figures I think there are a quarter of a million copies of the book now in circulation in Britain and North America. It’s being translated into many languages. I’m having wonderful conversations with translators who are trying to put together my tongue twisters. But more exciting is how it’s been taken up in a grassroots sense as a sort of activist, alchemical catalyst, I suppose you could say. Fundraisers have sprung up across Britain, and increasingly in North America and Canada, to raise money to place copies of the book in every primary school in a given city, county, country. At the very first one of these, somebody raised nearly £30,000. A bus driver raised nearly £30,000 to put a copy in every primary school, secondary school, and special school in all of Scotland, and the last of these are now being delivered a year and a half on, some of them by sea kayak, some of them by boat, up to the remoter schools on the more distant islands; and whole networks of communities and individuals have come together to take these books into schools, to talk to children about conservation, about nature, about loss, about creation, about how to make habitat. It’s also been adapted into theater, into film, into many kinds of music, from experimental classical music in America to a huge folk music concert and album in this country. Card games, puzzles—it’s nothing to do with us anymore: it’s to do with love and hope and fear and loss.

EMIt seems to have struck a deep chord within people to have this kind of reaction, and because it’s much more than the fact that adder or bluebell or wren or kingfisher has been removed from the dictionary; it’s what it means, and what people are reacting to, which is tremendously inspiring to see—that that many people are up in arms about what it means to lose these words from the basic list of words that we think are important to teach children.

RMAbsolutely. It is inspiring. And what’s been particularly exciting to me is how it’s been used to break down limits. It’s not that it’s just going into rural schools in remote, mountainous parts. It’s going into all of London. A charity is delivering a copy into every inner-city school. I’ve taught it in schools where forty to sixty languages are spoken on the playground. There’s nothing exclusive about this. This is inclusive.

It’s being used a huge amount by people working with refugee groups and domestic abuse survivors. It’s in hospices. It’s become the walls of a five-story hospital, where children are rehabilitating from orthopedic injuries. It’s the lost words of those who are suffering from Alzheimer’s and associated degenerative diseases. It’s being used to call those back. It is about nature, but it’s also about what language can do metaphorically at a bigger and more mobile phase, as it were, and that’s why I say it’s nothing to do with us anymore. We happened to have made this thing and released it, but it’s become this sort of open-source software almost and people adapt it. We try and make that as possible as we can wherever people want to make things with it. They take it into inner-city schools to do performances with the children there.

Rebecca Solnit tells these fabulous stories of hope in the dark. She says, “Never give up hoping, because the most extraordinary things can cascade from the tiniest of triggers”; and this has been my small involvement in a story of hope in the dark, and I feel very, very lucky to have been part of it. But as I say, it’s about far, far bigger forces and circumstances that are absolutely of our Anthropocene moment.

EMHmm. Well, could we close out our interview together and share a couple of these spells?

RMYeah, I’d love to do that. I’m going to read a sort of happy one first, as it were, so I have the book in front of me now. If you hear me breathing slightly more heavily, it’s because I’m trying to pick the thing up.

So, this is “Otter,” and otters are actually having a wonderful time of it in Britain at the moment. They were heavily endangered due to river pollution and persecution in the 1970s. They’re now back in every English county—that’s a real conservation success story in this country. If you listen you might be able to hear the O-T-T-E-R spelled out, but I wanted to create a kind of tumble-turning water twister of an otter spell that children could speak, and here goes.

“Otter enters river without falter—what a supple slider out of holt and into water. This shape-shifter’s a sheer breath-taker, a sure heart-stopper, but you’ll only ever spot a shadow-flutter, bubble-skein, and never (almost never) actual otter. This swift swimmer’s a silver-miner, with trout its ore it bores each black pool deep and deeper, delves up-current steep and steeper, turns the water inside-out, then inside-outer. Ever dreamed of being otter? That utter underwater thunderbolter, that shimmering twister? Run to the riverbank, otter-dreamer, slip your skin and change your matter, pour your outer being into otter, and enter now as otter without falter into water.”

EMOh, that’s beautiful.

RMI don’t normally get all the way through without tripping up on an otter.

EMWell, it does have that tongue twister quality to it, doesn’t it? That was beautiful.

RMThe amazing thing is that Jackie Morris has now memorized that, so one of the things she does on stage is she paints an otter using Sumi Japanese ink and water drawn from rivers in which otters live, and she speaks the otter spell while she paints these incredible otters out of water. She summons them back right there.

The one I’ll end with is one that’s already been read at a couple of weddings and a couple of funerals, as they say, and it’s called “Lark”—and skylarks are not having a good time in this country. They’re heavily down due to their nesting habitats just becoming diminished, and of course they have this extraordinary reputation for their song, their song of joy. You know, nature doesn’t just cheer us, it can also sadden us, as we’ve discussed. We all have our mental health challenges, and when I was writing this, I was having a tough time and I was thinking about depression and I was thinking about joy. This is the lark spell, which is about all of those things tumbled up into one.

“Little astronaut, where have you gone, and how is your song still torrenting on? Aren’t you short of breath as you climb higher, up there in the thin air, with your magical song still tumbling on? Right now I need you, for my sadness has come again and my heart grows flatter, so I’m coming to find you by following your song. Keeping on into deep space, past dying stars and exploding suns, to where at last, little astronaut, you sing your heart out at all dark matter.”

EMHmm. Yeah.

RMThat’s been sung by an amazing musician called Jim Molyneux. Incredible setting that stops me short every time I hear it.

EMWell, it’s been an absolute pleasure to speak with you today, Rob, and to get a deeper sense of the breadth of your work and the power of language to bring us into both deeper awareness and deeper connection with ourselves and the landscapes around us. So thank you so much.

RMThank you. I’ve enjoyed our conversation immensely.