Mud and Antler Bone

Martin Shaw is a writer, artist, teacher, and mythologist. His books include: Smoke Hole, Courting the Wild Twin, Wolf Milk: Chthonic Memory in the Deep Wild, The Night Wages, and A Branch from the Lightning Tree. Shaw’s translations of Celtic folklore and poetry (with Tony Hoagland) have been published in Poetry International, The Mississippi Review, Poetry Magazine, Orion, and Kenyon Review. He is the founder of the Westcountry School of Myth, a learning community located on Dartmoor in the far west of the United Kingdom.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His first book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

Ben Suliteanu is an aspiring filmmaker specializing in editing and sound design. He recently graduated from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in science, technology, and society.

In this interview, Martin Shaw offers an extended reflection on the intelligence that lies at the heart of myths. The best stories, he says, ought to be trailed not trapped, and approached with discernment, an open heart, and an attuned ear. He began our conversation by telling the story of “The Lindworm,” an old Norwegian tale about a mythical creature that is part human and part snake.

Transcript

Martin ShawOnce upon a time, there was a great kingdom, and in the center of the kingdom, there was a King and there was a Queen. And the good news about these people is that they were sweet and generous and kind. But at night, when they went to bed, there was a grief that hung between the two of them. And it was just very simple: the Queen could not conceive a child. They tried everything, but nothing worked.

So one day she’s walking through the gardens of the castle; she’s getting from the trimmed lawn out into the deep old forest. And from that forest came an old woman. And in a fairy tale, you know trouble’s coming when their little head bobs. So this old woman with this bobbing head turned up, and she spoke to the young woman and said, “Why are you grieving? There is something melancholic in your heart.” And the Queen told her what the trouble was. And the old woman said this very simple thing to do: “You need to speak your desire, you need to speak your longing, into a little cup. And tonight at dusk in the northwest part of the garden, walk along, breathe your desires and longings into the cup, give it language, give your desire language, and then flip the cup onto the dark soil. In the morning, when you come back, pull the cup up. There will be two flowers. Whatever you do,” said the old woman, “eat the white flower, not the red.” And with that, she’s gone.

So, next day, down she trots to the garden—she does indeed, the night before, breathe her longing and desire into language and onto the soil—and opens up the cup: there’s the red, the white flower. I don’t know why it is in our lives we do this; but we do it, even with the best advice in the world. As her hand moved for the white flower, it could not help but flip in the air to the red, and she guzzled the red flower down. Instantly, the Queen recognizes she is pregnant. There is some spark of light in the lonely croft of her hips, and a baby is on the way. Time passes, nine months pass, and the baby is born.

Now, a strange thing happened. It’s a dark night, it’s a rainy night, and they’re in a little tower. There’s the midwife, the doulas, the old women that are singing the ten thousand secrets that need to be in a woman’s bloodstream as she’s giving birth. And as she pushes the baby into this world, what scuttles out between her legs is not a child at all: it’s a small black snake, what we call a worm. The old doula sees this freakish little thing, grabs it, and throws it out of the window. Seconds later comes a beautiful little baby boy. From that point onwards, no one says a damn word about the snake. It simply never happened. We all have amnesia about it. But the old woman remembers hurling that snake far out into the forest, sending it into exile.

Now, the other boy grows up, and he’s healthy, he’s in great shape, until he gets to the age when he wants to marry. And he goes out on a horse looking for a woman to find as his bride. As he is moving through the forest, he comes to a crossroads. And at this crossroads, rearing in front of him is this vast black serpent—steam from its nostrils—and it says this: “Older brothers marry first.” He turns on his horse; he tries to go some other way. All day long, at every crossroads he comes to, the serpent appears: “Older brothers marry first.” It’s as if, at this moment in his life, there is only one place he can go.

So that night he goes back to his mum and his dad, the King and Queen, and he says, “Is there anything you didn’t tell me about my birth?” And they say, “No. Let’s go and see the old midwife, see if she remembers anything.” And the midwife indeed recalls that, “Well, there was this strange incident with the black serpent that we hurled into the forest.” Clearly this being has grown in strength, grown in power, and now is looking to marry.

And this is an amazing moment in this story, because the King and the Queen said this: “We must make a room in our home for the serpent. We don’t want to try and have it executed or assassinated or brought down by soldiers and mercenaries. We have to bring it closer.” And the King and the Queen sent the most beautiful of minstrels and musicians and poets to actually court the snake into the castle, where there is a big room filled with hay and newspapers, and they settle the thing down. And they send out word all over the kingdom that, indeed, there is a prince looking for a bride. Now for a while, many women come to marry the prince, not really knowing who he actually is. One by one by one, they’re eaten. One by one by one, every morning there’s nothing but bones on the floor. So after a while, the castle gets a reputation: they call it the place you go into and never come out.

So, the King and Queen are surprised when word comes from the edge of the kingdom that there is one woman still prepared to marry this beast. But she says this: “I want one year and one day to prepare.” And they say, “Well, of course, whatever you want.” Now, you should know that this young woman was the daughter of a shepherd, and she was very friendly with the forest; the forest would speak to her. So after she’d said she was going to do this, she was wandering the forest saying, “I’m marrying a serpent. I don’t quite know what was possessing me to say this. What do I do?”

And sure enough, she was sitting when she said this by the roots of an old oak tree. From out of the center of the oak tree comes an old woman with a bobbing head, and she says this: “You must prepare twelve wedding shirts—they’re like nightdresses—one after the other; and on each of them, you are to sow beautiful designs around the area of the heart, where your heart will be. Spend time on these dresses, do not hurry these dresses, do not speak of these dresses to anyone else; but educate your heart. Then, on the night of your wedding, wear each of the dresses to bed. You will not know what to do next. Also, bring into the chamber one great bath of milk and one great bath of lye—lye is water and ashes—also two great metal scrubbing brushes. That is the advice I give.” And with that, the old woman disappeared back into the tree and is gone.

The year and a day pass. She comes to the castle. She marries the serpent. Even as the serpent wraps its tail around her, rather than panicking like the other brides, she just looks over and says, “Yeah, that’s my husband. That’s my husband.”

They get into the chamber, and he says, “Take off your dress.”

She says, “Ah, I’ll take off one of my dresses if you take off one of your sets of scales.”

And he says, “No one ever asked me to do that before.” And he does it. And man, it’s a painful thing, much screaming, but he does it.

He says, “Take off one of your dresses.”

“I will if you take off one of your layers.”

You can imagine the furor. Hour after hour, layer after layer after layer, the serpent takes off his scales; until finally, underneath him—it’s a little like a worm. It’s this kind of glowing mass. There’s not a beautiful young man under there: there’s a freaking mess.

And it is then she gets out the scrubbing brushes. It is then she puts it in the lye (the ashes and water), mixes it all up—it’s an old sign of grief—and she starts to scrub on the flesh of this being. And if you thought he shrieked before, this was a whole other thing. Another hour she works on him, until underneath that is indeed a man with a face that looks like he was sent into exile seventeen years ago, a man filled with ordinary beauty. And it’s then she carries his body into the bath of milk. And gradually she washes him clean.

In the morning the King and Queen turn up, and of course they’re expecting the scene to be exactly like all the others: the bones everywhere and him saying, “Older brothers marry first.” They open the door to his chamber, and what they see is a young man and a young woman in, as the Irish say, radiant contentment.

And as far as I know to this day, in that kingdom that is inside you and everywhere else as well, there is a woman with an educated heart, and a man that learned to shed his scales.

So, that’s the story.

Emergence MagazineWow, it’s beautiful.

Martin ShawYou know, I always say to people, don’t try and understand the story, don’t turn it into an allegory, don’t find your way from beginning to end, just work into the image that has claimed you. So, if I asked you now, where do you find yourself in that story, which image—where would you be do you think?

EMI guess that the last part of this experience of being made clean again sticks with me. It also feels like a certain sense of vulnerability is what I’m left with, actually, at that moment of the story.

MSYeah, yeah, yeah. I love the fact that when the scales are off, he’s not beautiful: he’s a mess. You know, he’s descaled. But the beautiful image of the milk, the restorative milk—these are old alchemical images secreted away in fairy tales. A lot of magical information in this story. And often when I would tell it—I could tell it over two days, maybe, not ten minutes. But part of what myth can do is—you can tell them in a powerful, simple, quick way. But a real myth teller uses it rather like a concertina. And there are things in that story—when it’s told efficaciously, when it’s told well—which can be [done] very simply—that in the hearts and minds of the audience, the participants in fact, think, “That happened to me this morning. That moment happened to me before I even did the school run.”

So, in some way, I believe that many of the stories that we need right now in our culture arrived perfectly on time about five thousand years ago. And this is for sure a very old story.

EMSo then how would we learn to listen to those old tales again and glean the meaning, the essence of what they held, as we look around us searching for new stories?

MSFirst thing we gotta do is trail the stories not trap them. If you trap a story, you’ve put it in a little allegorical cage where you pretend you know what it means. The moment you think you know what the story means from beginning to end, it’s lost its nutrition, it’s lost its protein, it’s lost its danger.

Seamus Heaney, the poet, says that a poet is somebody with a tuned ear. And in a way tuning your listening to stories is a discipline. You know we are living in a world where people spend endless amounts of time in the gym, endless amounts of time toning their body, but their minds lack discipline. You know what it is: you have to let a story have its way with you. You can’t tell the story what it is. You learn to sit in the radiance of it until something comes from the story that disturbs you or bugs you or makes you happy, until you have to do something with it. But that is not the same thing as using a story to make a psychological point or to support a contemporary polemic.

Because I’m a storyteller and a writer, people are always saying to me, “Can you find us a story so we can make this point? We wanna make a point about climate change. We wanna make a point about gender. Will you send us something over that supports it?” Now that’s backwards to me. Story is first. You have to be in the presence of the story, which I regard as a living being: it’s a wild animal; it’s got tusks, udders; it’s got a tail; it doesn’t behave; half the time you want it to be there it’s disappeared, it’s shuffled off somewhere else. Stories should be filled with so much consequence and danger, they won’t behave for your polemic. And so, I go to a lot of places where people claim, “Hey, it’s all right, Martin. It’s good. You can retire, because I have created a new myth for now. I’ve taken the best bits of all the stories, from all round the world, and I have cut and pasted it into something that fits perfectly our time.”

Now I have strong opinions about that, as you can probably tell. And I would also use a quote from Joseph Campbell, and he said this: “We all gag on true doctrine.” And what he means by that is there has to be roughage in a myth that you do not understand or even find palatable, because otherwise you’re just talking to yourself. It’s a form of hypnosis to create a story where the only face looking back at you is a human face.

Old myths are not necessarily always coming from a human point of view at all. They are a multiplicity. In actual fact, every day that we get up, and we eat our oatmeal, and we go off to work, there are competing stories within us trying to be told. And actually to have a tuned ear to be able to listen to myth in the way that you’re describing, requires a kind of discernment, to know within you all of these different stories that are trying for primacy—which ones do you attend to, and which ones do you actually tune out?

Because one of the things a myth tells us is that you can’t listen to everything all the time. That way lies madness.

EMHmm. So this concept of listening isn’t just about listening to the story as it’s being told to you but would be part of the process of how the story was told to begin with?

MSYeah. Here’s the thing. I think when you first hear a story being told orally, forget everything other than just the sheer experience of hearing the thing. You don’t have to think about how it relates to your life. You don’t have to psychologize it. You don’t have to do anything other than just bear witness to it. Because stories trade in a kind of—it’s a word, it’s a beautiful word I use sometimes: chthonic—they work in chthonic dimensions. In other words, if a story lands immediately in your logic, if it immediately is neatly trimmed and makes perfect sense, it’s not really doing its work. Stories, old myths, do a kind of open-heart surgery on you. And at the time—usually when I’m hearing a story of tremendous power, I know something is happening, but I don’t quite know what it is. It’s as if some vast presence is just passing me in the dark. And over the weeks that follow, to use an old Irish expression, I brood. I brood on the images that really touched me during the story. And it is then that whatever is trying to surface in me, to express itself from the story—I begin to get some comprehension about it. But it doesn’t generally go down a logical or heroic route.

EMThat makes a lot of sense. And I guess, a follow up to that would be going back—outside of listening to a story or even telling a story—to this larger question: How do we go about creating stories? And what role does listening have in the creation and telling of stories?

MSThere’s no way we can’t create stories, which are the things that really feed our bones; that’s what we’re hunkering down for. Stories bring in what is at the edge of our vision and not right at the center. So in other words, in an old myth, if there’s a crisis in the story, the remedy for the crisis always comes from the edge not the center. So when I think about the times we’re in, and I think about what is actually happening to our gaze—what we are fundamentally staring at all the time—I think, that’s not a mythological move. A mythological move is to be aware of all the hundred trembling secrets at the edge of your vision. Because they are the things that want to secrete their intelligence into you about the problem that’s right in front of you.

But if you think about great myth—if you keep staring at Medusa, you get turned to ashes. And when I meet a lot of activists at the moment, I meet a lot of people utterly consumed with the seemingly horrible narrative of our times. I see a lot of burn out, because they have no shield to reflect, they have no art to reflect, the immensity of what’s right in front of them. If all you do is stare into hell, you will become ashes.

Stories are a way, an artful way, of negotiating very difficult things in such a fashion that, in the very demonstration and articulation of those stories, more beauty works itself out into the world.

EMGoing back to something you said that really struck me, which was this notion of telling stories for ourselves—like we’re just telling stories, you know, repeating ourselves, reinforcing what we want to believe—and that being potentially part of the problem that we’re in. We’ve told the stories we want to be true rather than the ones that are. I wonder what you would say about that?

MSYeah. Stories could be utterly toxic. You know? Stories are not always—there are some stories we need culturally to walk right out of. I’m not presenting for a second the thought that everything that is ancient and old is good, and everything that is new is bad. It’s much, much more subtle than that. But I meet people who, in my language, are serving in the wrong temple. One of the things I do with folks that work with me mythically is to say: During a day, where do you put your time and energy? And who is the deity that stands behind your time and energy? In whose temple do you serve? And that can take a long time to think about. Do I spend a long time thinking about money? Am I basically living a poetic life? Am I living a life that draws me to the ocean? Are you a son of Poseidon? What temples am I drawn to? That’s a great way of beginning to think mythically—and not just as a form of exercise, but understanding the powers that are compelling certain decisions in your life and shaping it, to a certain degree.

So the more you understand what Blake would call these “divine influxes” that come through you, these passions, the less likely you are to be possessed by them. And a story goes toxic when you are in a possessed state, and in other words, you are living a life without any kind of reflection in it. That’s when you find that, really, you’re living a story that’s little more than a trance state. And when you are living in a variety of trance states over a day, you are hugely, easily manipulated.

And so myth—the difficulties and challenges within myth are not to enchant the listener, they’re to wake the listener up. That’s what the stories are trying to do. They’re trying to bring out your sovereignty. They’re trying to say, you should walk naked down the royal road to the secret treasury of myth and story that everybody around you wants you to forget.

In Gnostic societies and cultures, there’s a belief that on the night you were born, you had a twin that was thrown into exile—we all have one. And the business of being a functioning adult, with all the complexity that entails, is that at certain points in your life, you seek out the wild twin that culture at large wants you to ignore. So you gotta be in touch with your own senses to do that. You’ve got to be un-tranced. You’ve got to be woken up. You’ve gotta know what you stand for. You gotta know what you’re gonna defend. You gotta know what music you like, what colors speak to you—the whole thing.

James Joyce used to use a fancy phrase for this: he calls it “aesthetic arrest.” And all aesthetic arrest actually means is, what are those one or two images that have utterly claimed your heart—claimed [it] beyond thought, claimed [it] beyond the temporary fashions of culture? And you are just forever in love with two or three things. And then the idea is, if you work out of them, if—to use that phrase I said earlier on—you let them have their way with you, then a life of real good trouble can be bequeathed to you.

If you’re over the age of twelve and under the age of ninety and you’re not in some kind of trouble, what the hell are you doing?—is what I think.

EMSo there are individual stories, and there are collective stories, and there are stories that transcend culture and transcend boundary that is imposed by our modern world. And as you said, a lot of the stories that are told are ones that put us in a trance-like state, that can manipulate us, that can control us. So I’m really curious to get your take on this collective story or myth, if you will, that has entranced us—this idea of progress, some call it, that we can do anything, that we are the gods, that we are in control—and that impact on us individually, and then collectively, as we deal with the challenges we’re facing.

MSI think something happened, way back, where some visceral, vital—to use a big word—animistic relationship with the earth got lost. And what we have now a lot of the time is—stories I come across all the time—very well meaning people providing news stories about the earth and the state of the earth, and statistics about the time we’re in. Statistics will not help us fall in love with anything, at this point. The hour is very, very late. And what we need is a great, powerful, tremulous falling back in love with our old, ancient, primordial Beloved, which is the Earth herself.

EMThis falling back in love that you say needs to happen—a good story, you know, doesn’t always make you fall in love. Some do. But regardless of whether this story is about falling in love, there is the need, I think, for stories to try to create that sense of relationship with what was once a love affair but is now one which is purely as, you know, convenience for resource to serve my own interest.

MSOne of the things that always alerts me that I’ve fallen in love with something is that I don’t tell it what it is. I don’t put it in an easy category. I simply pay attention to it. I behold it. There’s a difference between seeing something and beholding it. If you see a tree, you could look at it as various bits of two-by-four and what you’re going to turn it into. But if you behold a tree, you’re into many layers of relatedness. You’re into a different thing.

And so the stories I think we need—as I said, we don’t wrestle them into allegory or polemic, we just sit in their presence for a while. I’d also say this: there is something about Western myths and narratives that begin here and they end there that is not so common in many indigenous cultures. In many indigenous cultures and older forms of story cycle, you would start a story at almost any point depending on where the energy was with the people at that time, or the place that they were in, the movement of the crows overhead. So in other words, the beginnings and endings are by no means as fixated as we have in the West.

There’s a writer, Camille Paglia, who says, “We are, in the West, addicted to climax.” If there has not been a climactic ending to a story, there hasn’t been an ending at all. But in myth, the end of a story always jumps into the mouth of its beginning; it’s that cyclic relationship we talked about. And so there are storytellers that will say, and say truly I think, “The world as we love it will not come to an end, provided we keep telling stories with the earth speaking through it.” Because by their very nature they bring us back into creation and the beginning of things over and over and over again. So a story well told is essentially restorative every time it’s told.

It’s an interesting thing you were saying about—does a story necessarily call us into falling in love again or not? Love is a complex word. There are many chambers to the heart. But one of the things that I’m curious about in my own work is, why is it that certain stories are utterly compelling to us while other ones we brush off and never think of again?

So I am interested in the relationship of love to stories. And not just what you would call eros, not just the kind of inexhaustible energies of the universe and the play of them, but actually stories that we miss when we’re not telling them or being told by them. Why is it that, here I am in California, I am in the presence of some of the most beautiful landscapes imaginable, but my heart pines for where I come from? It pines for Dartmoor. That’s not just eros, that’s an old troubadour idea. That’s amor, a-m-o-r. Why is it you love her and not her sister, or her mother? Why do you love her?

So what is that distinct idiosyncratic relationship with a particular stretch of land, or a particular stretch of story, that compels us, again and again, to be in its presence? And so, I don’t think I ever talk about saving the earth; I just don’t think like that—because, as Tom Waits says, “a song needs an address.” So if you’re gonna talk about anything, tell us the address man, you know. Tell us about that oak with the moss on the northern flank. Tell us about that curve in the Missouri River where the salmon do not come back to anymore—and our heart starts to exfoliate again.

EMSo in some ways, you’re talking about remembrance and how being in relation to that place, this constant calling to remember it, to be in relationship to—

MSIf you love something, does it not affect the way you behave? I’m surrounded by people telling me, these are the end of days. I’m surrounded by people telling me that statistically there is no way out. Do you think I’m gonna take that remotely seriously? No. Because life is more magical than that. Stories are far more unexpected than that. And whilst I think it is utterly appropriate to bend our heads to the grief of our times, I’m not, as a father, going to be telling my children anytime soon that all is doomed. That’s too morose a timeline for me.

EMSo what is the story you tell your children then?

MSI tell the kids—whoever they are, wherever I happen to be, whatever kids I meet, of whatever age—you were born for these times. God Almighty, this is like you’re sitting at Camelot’s table. This is the moment to take courage, to raise yourself, to proceed with a degree of urgency, I would say, with a sense of humor, but to know that the mechanics of this time, the quests of this time, are utterly mythical in nature.

Of course, every generation says we’ve never lived through anything like this before. But we have really never lived through anything before where we are now. And I think an old expression of Carl Jung, of all people, is really interesting. He used to talk about the lament of the dead. And he said, the problem with the times we’re in [is] that if you can’t hear the lament of the dead in the way you respond to certain challenges, you’ve cut off all your ancestral connections. And I would volunteer this as a thought: if you don’t have ancestors, you have ghosts; and you end up living a very haunted life. No matter how much money you earn, no matter how much tenure you may get, no matter how much success in the world you think that you want to run after, you are haunted and surrounded by ghosts. So stories—your capacity to tell a story, to stand for a story, to let a story work through you, will help you articulate the lament of the dead. I’m not talking about séances, we understand. I’m talking about knowing the ground that you stand upon.

EMAnd so maybe collectively you’re saying that we are cut off from our ancestors and surrounded by ghosts?

MSSome of us certainly are. I think one of the things that really needs to come forward in our exploration of myth and stories—especially in America, of course—is stories of migration, stories of emigration. Because when I work with people outside of Europe, many of them, their parents, or maybe their grandparents have gone through enormous peril, personal peril, to get them to Turtle Island, get them to the land of the far west. America is interesting for me as a British person, because mythically whenever the boats sail west in a story, you are sailing into the other world—whenever you sail west in a story. That’s where Arthur goes to heal. It’s also where people go to die. So from my very first time of arriving ten years ago in America to this very second right now as you interview me, I am never without the sensation that I’m in the other world—which is this one when it wants to be.

EMBut then this “other world” has become the world as we know it, as America has overtaken so many other cultural stories, even in England, right? So what are the implications of that as far as the power of story to shift us, to trance us, to move us, to challenge us?

MSHere’s the bad news: We are not going to get a story worth hearing until we are broken open by our own consequence. And I’ll say that again. We are not going to get a story worth hearing until we are broken open by our own consequence. That’s where we are. That’s what the time is. That’s what myth is telling us.

So the catastrophes that are moving around us right now—the pandemonium, the deep depressions that many of us feel—I’m absolutely convinced are part of the trade of the breaking-open-into-something that is truly and profoundly real. But you cannot put a sticking plaster over the Grail King’s wound, to use a mythic image.

Much opportunity is heading toward us disguised as loss. And we’re going to need stories—deep, powerful, alchemical stories—to help guide us through such a time.

EMSo what are some of these opportunities that are coming to us in the form of loss?

MSDramatic lifestyle changes, for a start; things that feel like infringements on our freedom. We are living in a time, I would suggest, where choice is almost tyrannical now. You know, there are so many endless possibilities, we’re actually frozen like rabbits in a headlight. We can’t choose. Imagine now if you said, Oh, I’m gonna become a student of myth. Hundred and fifty years ago in the valley where you and me would have grown up, one story coming through for the winter, one big, one new fairy tale—that’d be enough. Now, I can’t move. I look one way and it’s Tibet; I look another way, it’s Amazonia; I look another way, it’s Arnhem Land.

The capacity to be three miles wide and two inches deep is, I think, becoming one of the passports of our time; that’s how we think we’re sophisticated. We know a little about an awful lot of things. And myth usually is trying to do the opposite. And the myth asks us a question: would you trade growth for depth? So in other words, you are no longer the man or the woman that walks from flower to flower to flower to flower to flower. You actually decide to marry something. Because if you constantly move from one erotic to another to another, you are a gigolo, not a husband. My concern is that the stories don’t even take us seriously anymore. People say to me, “We can’t hear the old gods.” I wonder if the old gods can’t hear us ‘cause our language is so damaged. I wonder.

I was on a plane the other day, flying from England to California, and it was one of these old planes where they had a screen for a movie but you had to have headphones to hear it. So I couldn’t hear the movie, ‘cause I wasn’t gonna pay for the headphones. So I just sat there for ten hours watching movie after movie with no sound. And I wondered as I watched this movie, is this what it’s like for the gods now? Is our language nothing but static to them? I wonder [if] it’s not that we can’t hear the gods: the gods can’t hear us.

EMThree miles wide, two inches deep. That brings up this question of relationship to place, which you’ve been talking about, and how, if you don’t have a relationship with a patch of earth—that you have been in relationship [with] for your life, or the majority of your life, and maybe your parents and their parents’ parents, and so on—how can you be anything other than three miles wide and two inches deep?

MSWell, I’d like to respond to that. That’s immediately a huge problem for a lot of people who, whether they wanted to or not, have moved from many different places. This is what I would suggest: think about the difference between being from a place and being of a place. So in other words, I come from a stretch of England where I’ve had relatives living there for two hundred years. However, [for] many of the people that I meet who have been there for a long time, that is not a passport necessarily to deep spiritual literacy of that area. They can be utterly oblivious to it. That’s being from a place.

To be of a place is something a little bit more subtle, and it involves you being alive to your own sensibilities. So here’s an example. I have a friend called Satish Kumar. Satish Kumar walked out of India with no money in the early to mid-sixties—walked across the whole world—and then he gets to this little stretch of moorland where I come from, called Dartmoor. And Dartmoor takes this small Indian monk and says, we claim you. And it did, and Satish has loved, profoundly, Dartmoor ever since. And when Satish speaks of the place, this place radiates through him. He’s as indigenous to Dartmoor as the River Dart, as the salmon in the Dart, as any of the bones of my ancestors in there—because in some way, it has cooked him.

So, in other words, what I’m trying to say is not to get caught up with matters of race so much—although of course that has a part to play—but to keep open to the fact that whatever your age is, there could be a place that wants to reach out and say, “Hey, stop. I’ve got something I want to say to you.” And you cannot hear it until you slow down, till you stop multitasking, till you stop looking only at what is a foot and a half in front of you, and pay attention to all those trembling mysteries of that place that we just spoke of.

So, being from a place, being of a place—then there’s another question I would have for anyone who is really interested in these things: are you prepared to trade comfort for shelter? Because one of the ways we are so entranced now is this idea that we live in scarcity in the West. There’s a spiritual scarcity, for sure. But in terms of, you know—we have central heating, we have twenty thousand different types of bread, only several hundred yards from here, I’m sure. We are adrift in possibility.

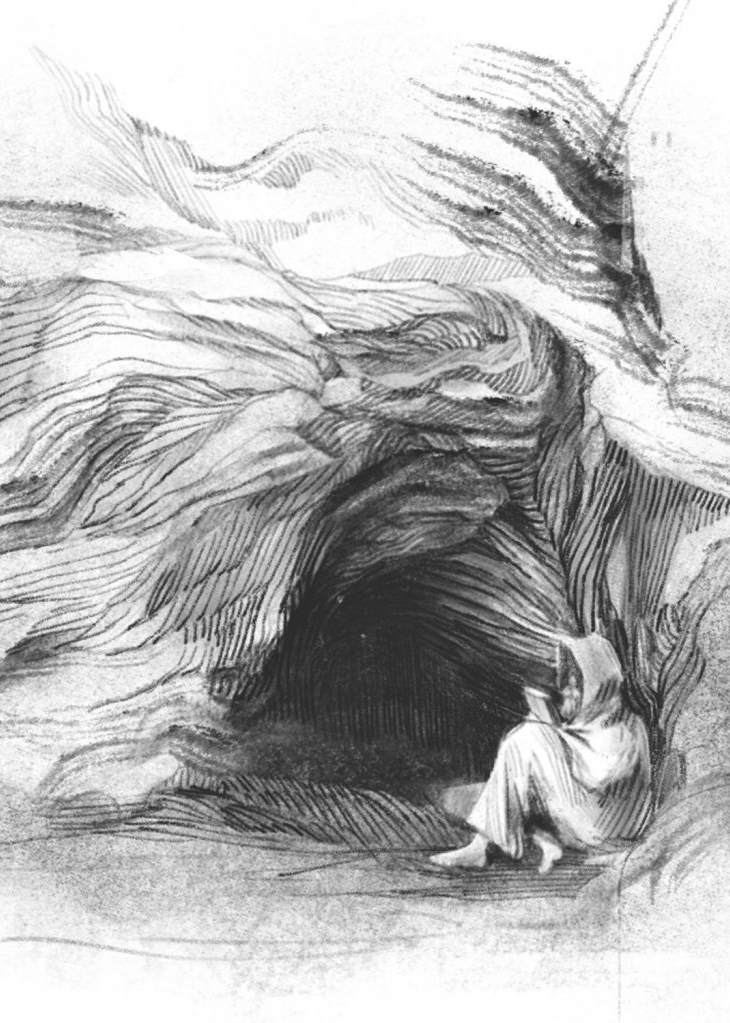

But when I was younger, when I wanted to get serious about myth, when I wanted to get serious about place, when I wanted to live a story broken open by my own consequence, I went out into the bush and I lived in a tent for four years. And I didn’t do it somewhere as dramatic as the badlands of South Dakota, or Siberia, or stretches of Australia. I just did it where I come from. I explored for four years, in a little black yurt, remaining pockets of English wilderness.

So to do that I had to trade—this is a subtle idea—I had to trade comfort for shelter. I had to make my own heat. I had to cut my own wood, make my fire. I lived in a circle that, when the winds come and the weather comes and it can rain for months and months and months at a time and be petrifyingly cold, I was not given necessarily comfort by that tent; but I was given shelter. The walls would breathe. You know what canvas walls are like: they breathe, they’re porous. I wanted to be buffeted by weather. I wanted to see if I could still draw the marrow from the bone of Old England. Almost killed me in the process, but that was my rookie attempt, that was my rookie attempt.

And you know what, the reason I tell stories, the reason I tell stories, is that the enormity of that experience required the dignity of a new form of speech. I couldn’t talk about it in “I” statements. I couldn’t talk about it like “pass the talking stick.” I couldn’t talk about it in a psychological framework. My language needed to have roots and mud and antler bone on them. And the place I remembered that contained that kind of life and energy was these stories I loved as a kid. So in a way, it’s been remembering not what I like, but what I love. What has claimed me again. And I wrote a book about it. I wrote a book called Scatterlings: Getting Claimed in the Age of Amnesia. I think that one of the most powerful trance states that we can be put under now is a forgetting that any of this matters, a forgetting that a sense of place, or a quiver of stories, really has any relevance whatsoever. So the book is far less about how well I did with that. It’s not that at all. What it is, is an invitation in some fashion to try and draw something from that book, which claims this: Wherever you are in your life, no matter how diminished and small you may feel, your incompleteness is your authenticity. Just the very sense of longing in you is the—you know, as Rumi would say—is the voice of God speaking back to you.

So start with your incompleteness. And when you feel your incompleteness, I hope you have some calluses on your hand from giving yourself a little pat on the shoulder—that that’s where the journey begins, that’s where the great myths actually begin, with a sense of incompleteness. Otherwise you’d never leave the village. Otherwise you’d never get into trouble. Otherwise you’d never get your heart broken.

EMWell, in some ways, that feels like a good place to stop—where you would essentially start.

MSYes.

EMSo I wanna thank you very much for your time, Martin. A real pleasure talking with you this afternoon.

MSPleasure.

EMWonderful.

MSTake courage. Keep going.