Lia Purpura is the author of nine collections of essays, poems, and translations. Her work On Looking was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her awards include Guggenheim, NEA, Fulbright Fellowships, the Pushcart Prize, and the Associated Writing Programs Award in Nonfiction. She lives in Baltimore, MD, where she is Writer in Residence at The University of Maryland and teaches in the Rainier Writing Workshop’s MFA program. Her newest collections are It Shouldn’t Have Been Beautiful and All the Fierce Tethers.

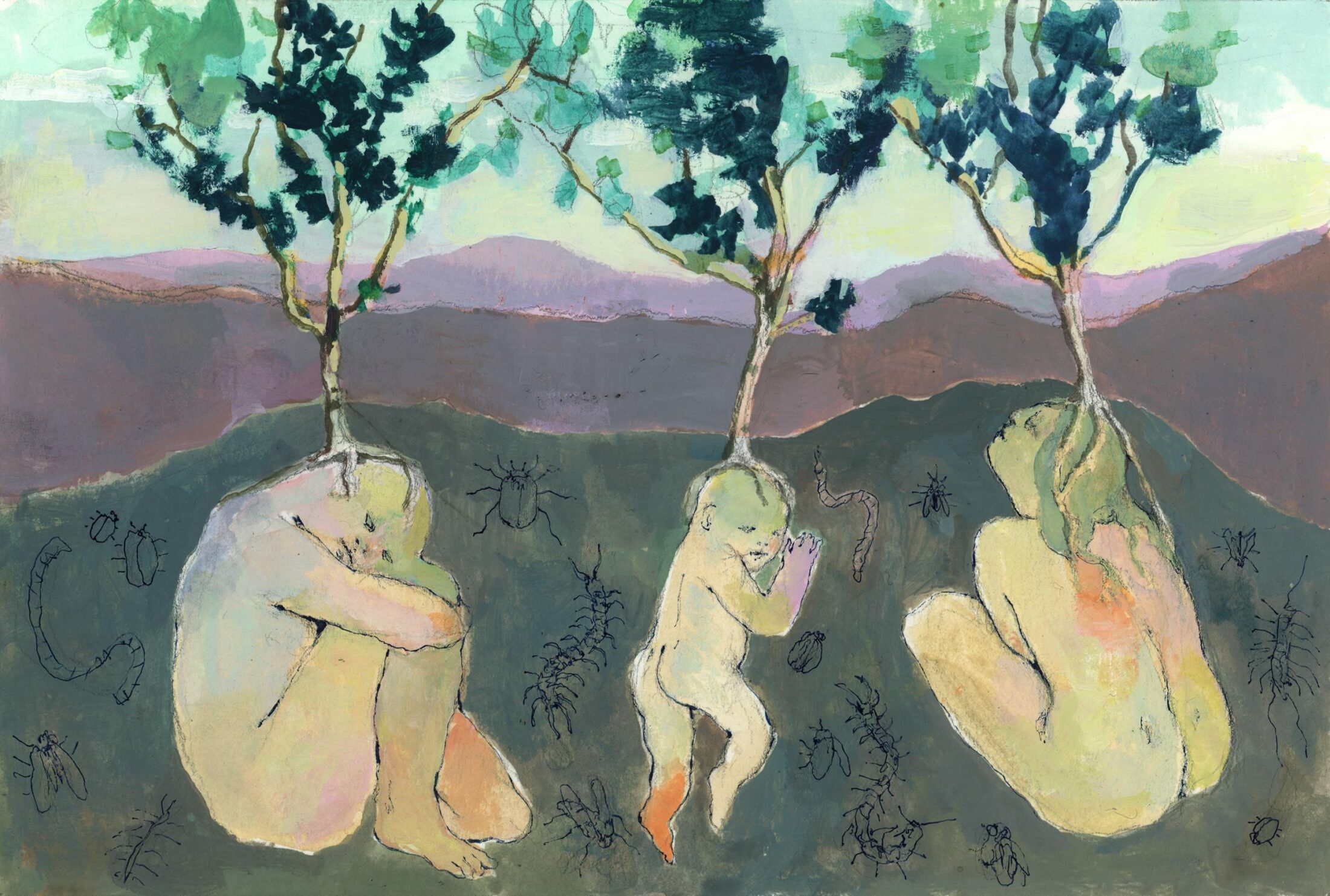

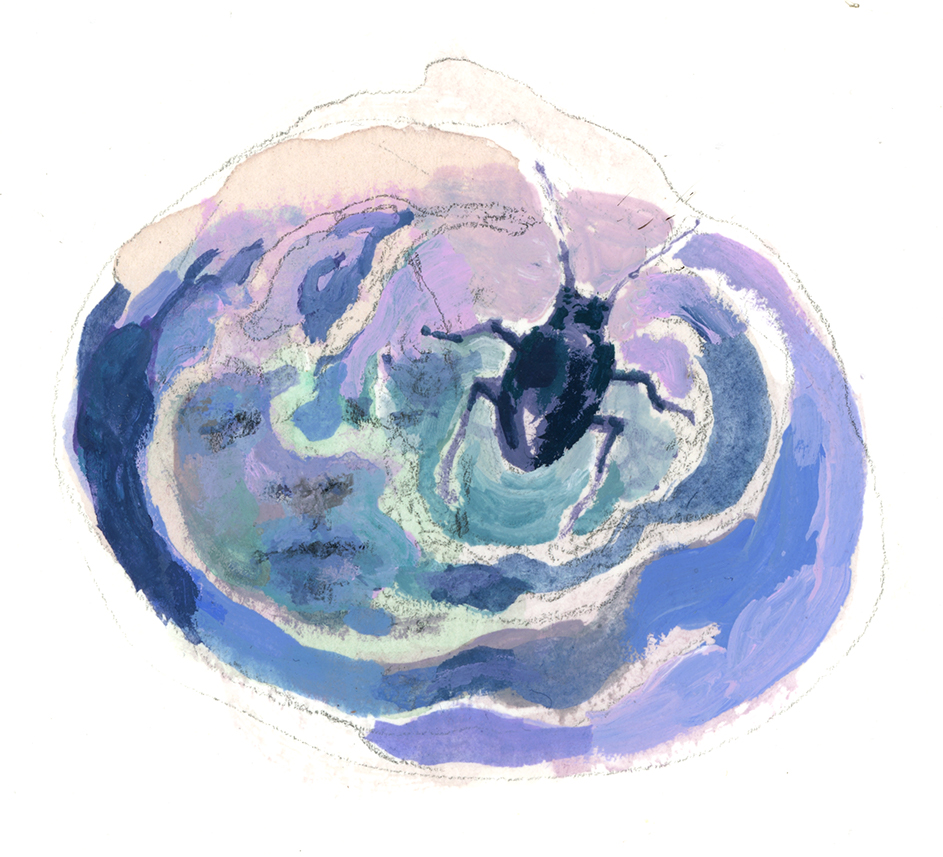

Jia Sung is an artist and educator based in Brooklyn. She is currently an art director at Guernica, teaching artist in residence at the Museum of Chinese in America, and teaching artist at the Children’s Museum of the Arts. She has exhibited work at the RISD Museum, the Whitney Houston Biennial, and La Mama Galleria. She is currently a 2018–2019 Smack Mellon Studio Artist and recipient of the Van Lier Fellowship.

Lia Purpura delves into the horrified wonder and holiness of death, exploring burial practices that are intended to nourish the earth, as it has nourished us.

Consider the holy work of buzzards—roadside in the summer heat, hunched over bodies steaming in cold, picking and tearing back to bone, savoring all that would otherwise rot. Floating on thermals, grounded in cut fields, buzzards are hybrids of elegance and utility, doing the labor unloved by others, the work of right endings, which is in itself a form of creation. To be made an enticement, an attractive morsel, smeared with yak butter and left on a mountaintop picked back to bone, in the way of Tibetan sky burial—I’d go for that if given the chance.

Hard to come by as an option in Baltimore.

Still, systems of regeneration abound.

Say, shopping in thrift stores—an easier way to keep the useful in motion. Slipping into another’s garment, my arm in his sleeve, leg in her jeans—a bequeathing, an inheritance. All those objects hauled from sheds, burnished with oil, sweat, rain, heat, dirt; all those flawed but able things, holding light still, inscribed by their days. At the farmer’s market, it’s the seconds I’m after. Peaches, tomatoes—not for the markdown, just that imperfections are misjudged. If choices were based on cycles and time, not hierarchies of beauty, then the seconds—speckled, soft, unround, and windfallen—would be firsts. The ones you know to take-now-and-eat, unequivocally ripe, who need us to complete them, or the sweetness they were raised up for is lost.

Conventions contain our messiness. You lean into frames and they hold and direct you. Until they don’t. Until the known forms no longer accommodate the shape of your need. As a rule, we hand over so much to the pros. In death to the death handlers, trained to organize our grief—funeral directors who stage presentation (casket or urn), offer gathering spots and golf cart rides, oversee the backhoeing and the limos’ return to the parlors of mourning. To alter the procedure requires planning most of us avoid, and stores of energy hard to conjure in grief. (Note to self in advance: consult members of the Order of the Good Death, a collective of undertakers, activists, mushroom decomposition scientists, writers, artists, medical historians, forensic pathologists, psychiatrists, post-mortem jewelry designers, who have much to offer in the way of choices.)

Not many folks plan on playing death rebel, but that’s what happened for historian Elizabeth Heineman, who, after the still-bearing of her boy, Thor, brought him home to—and what to say here?—live with the family for a while. She writes in her memoir, Ghostbelly, “Having your dead loved ones nearby used to be normal. But nowadays you’re supposed to keep corpses in their proper place, which may be the morgue, may be the funeral home, but most important it is somewhere else, away from the living. But this isn’t the law. It’s just that no one bothers to tell grieving families their options.” With the help of a wild funeral director, she upended and overrode, step by unknowing step. Here, her reasoning—as she says, neither spiritual nor religious—is at its most tender: “Why should the body that was Thor transmogrify from an intimate member of the family, from an intimate part of my own body, into a repellent object just because it had died?” Casting into the future, she realizes, “If we had no memories of Thor, maybe someday it would be as if he’d never existed at all.” So they read to and rested next to him, showed him his neighborhood, playground, and room. Thor had to be real before he could be gone. “As the days passed after Thor’s death,” she writes, “I realized with horrified wonder that I was doing something I had never done before, at least not since early childhood. I was having my own experience.… This was my experience, mine to invent.”

And what did she experience? Being-with in death as a reconstituting of time itself, a new way to ride days into meaning, to live out a proper cycle, albeit terribly foreshortened.

It’s vertiginous, this state of responsive imagining, especially when it arrives at raw moments, sidles up to the crack, and calls across the gap in our knowing. Emerson described the bracing sharp clarity of the imagination as “a very high sort of seeing, which does not come by study, but by the intellect being where and what it sees; by sharing the path or circuit of things through forms, and so making them translucid to others. The path of things is silent. Will they suffer a speaker to go with them? A spy they will not suffer; a lover, a poet, is the transcendency of their own nature,—him they will suffer. The condition of true naming, on the poet’s part, is his resigning himself to the divine aura which breathes through forms, and accompanying that.”

The divine aura which breathes through forms is a fearsome force, not wispy or gauzy, not soft-focus-benign, but sublime, full of “horrified wonder,” a vastness or steepness brought unnervingly close.

Why is it difficult to value the dispersal of our large selves to the very small?

In the spirit of fearsome wonder, let us look into and accompany the body.

To wash the body with one’s own hands. To comb, lotion, trim, dress. To choose an airy casket of wicker, or a winding sheet, wheat colored and flecked with chaff like a canvas stretched on a frame, made ready to receive some expression from within. To so love the body in its passing is to consent to many unexpected things: the giving over to helpers, for one. Those who know exactly how to proceed, whole orders of creatures made to meet the body and get to work.

Their activity begins with the body’s ceasing, a fresh settling where there are no outward signs of decay, and for a brief time no collapse or leakage or odor, though much internal movement is stirring. Then days after death, when the bloat comes on, scents rise and beckon very precisely to the first responders—coffin flies, who find their way six feet down. Blowflies, carrion flies, and their young fill the dark, shallow spots next, probing the pouches and channels of us. Our filaments unlock; we leak and are drunk. We reorder as gas, liquid, sugar, and salt. When the final crew comes to finish up—the skin beetles, centipedes, snails, and cockroaches—the slow descent can begin: the decades-long stretching, darkening, and drying; time collecting as it does on wood, where it gets called by its forest names, lichen/moss/fungi.

How it felt inside me, learning about decomposition? A mix of stomach-shifting vertigo, shivery tenderness, and wide-awakeness. There was the unexpected sensation of microbodies pulsing and gurgling below my own skin, compelled, called, directed. There they were, underfoot, unseen, flourishing in their cadaveric ecosystems, colonizing in orderly waves, each in its own time, and bound together creating “decomposition islands”—those organically rich plots made of us and fit for the blooming of others.

As impossible as it seems to balance the entirety of a singular life with the millions of roles it will play in millions of other lives, we need not try—ground, air, fire, rain, every element and direction have already conceived it. Carbon molecules that constitute us are broken down, rearranged, reattached; we come to be called by another’s name, but the matter of us doesn’t slip away, and the potential energy of our bodies is perfectly accounted for.

Though it’s a hovery state, this being neither-created-nor-destroyed, we are, all of us, born to it. We are not made to be nonexistent. And ongoingness—to have been sustained by and to now sustain others—feels, along the raw of its edges, in its startling certitude, holy.

If a fact is capable of being both true and holy, why is it difficult to value the dispersal of our large selves to the very small?

In their presence we chafe against the limits of Dominion. And Dominion as we’ve inherited it—that charge or blessing to “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen. 1:28, NRSV)—is, as a theologian friend says, “one of the most intractable issues in scripture.” Pope Francis, in his recent encyclical, is pretty emphatic about the D-word, “This is not the correct interpretation of the Bible as understood by the Church,” imagining instead that once brought into being, “Soil, water, mountains: everything is, as it were, a caress of God.” Another friend, a rabbi, wrote me recently, “Rashi, an early medieval commentator, ties ‘subdue’ to what man should do to woman … but we definitely go into the realm of stewardship in contemporary rabbinic discussions.” And of every micro world and wildly diverse organism at home therein, biologist Ursula Goodenough notes, “What a windfall it has been! Minute and enormous, beautiful and hideous, enduring and evanescent, independent and parasitic. They occupy the most impossible (to our eyes) niches: ocean vents, arctic snows, desert cliffs, human eyelashes. They form long complex food chains and, in the process, provision our atmosphere with gasses and our earth with soil and our biosphere with fixed carbon and nitrogen.” Dispelling the paradigm of hierarchies, she goes on, “We can only talk about how an organism propagates in a given niche, how its life strategies have become adapted to that niche. It is no more or less fit than any other kind of organism that has adapted to some other niche.”

Or as John Donne preached in 1628: “All things that are, are equally removed from being nothing.”

To imagine more fully what it means to live on, to give up the body unto the least of us, to be refit inside miniature frames and relieved of our centrality, is to enter into regions beyond normal perception—Blake’s worlds in a grain of sand and eternity in an hour. This is the realm of poetry’s compaction, its shape-altering and time-folding, its belief that the briefest words might touch states of wordless being.

Or as Nobel Prize–winning geneticist Barbara McClintock said of the microbeings she worked with all her life, “I found that the more I worked with them the bigger and bigger [they] got, and when I was really working with them I wasn’t outside, I was down there. I was part of the system. I was right down there with them, and everything got big. I even was able to see the internal parts of the chromosomes—actually everything was there. It surprised me because I actually felt as if I were right down there and these were my friends.” She goes on: “…as you look at these things, they become part of you. And you forget yourself. The main thing about it is that you forget yourself.”

Most essentially, at core and at large, we are exiled from the systems to which we belong.

To forget yourself is not the same thing as being forgotten.

The ancient Egyptians embalmed their dead elaborately with resins, beeswax, aromatic oils of cedar and juniper, gave them painted masks and alabaster eyes, stored their organs in beautiful, orderly canopic jars (leaving the heart intact, to be weighed sometime hence by Osiris against Truth). Their practices assumed an active afterlife, and so the corpse was wrapped in linen with amulets stashed in every layer, eye holes drilled in coffins so the dead could see their way out and back, doors drawn for exit and reentry. Not that one era’s prep for the ages incurred another era’s respect. The Victorians, mad for all things Egyptian, held mummy unveiling parties—pocketing the amulets along the way—and disinterred so many bodies that at one point it was cheaper to use the surfeit of mummies in the production of paper than it was to cut down trees.

Contemporary embalming practices, unconcerned with eternity, preserve the body only long enough for a brief viewing. Still, to stage a proper goodbye, there is much to be done. Eye caps are inserted under the lids and the eyes are sealed. A mouth former is fixed in place and the lips tied shut. Gauze is stuffed in the nose and throat to absorb fluids and hold shape. Wax molds reconstruct any missing parts. Anus and vagina are stoppered, and the stomach punctured, so the blood and fluids can be drained with a hose and formaldehyde and other preservatives pumped in. Hair is styled and beards are shaved. Nails are polished and makeup applied. To achieve that traditional state of repose, tendons and muscles are often cut, arms arranged and fingers intertwined, then glued into place over the chest. Far from the weird churn induced by those consorting microbes, these procedures read like desecrations. A chance to care for the body—all a body could be for the still-living, quieted now, able to be spoken to and touched before burial, the hair stroked, the ear traced—missed entirely.

Fears about unpreserved buried bodies contaminating land and water are common—another way our refusal of the end parts of cycles manifests. “The more pressing medical issue related to embalming,” reports the Green Burial Council (GBC), “is the risk to embalmers and funeral directors from inhaling the vapors of embalming fluids, which contain, formaldehyde, benzene, ethanol, ethylene glycol (an ingredient in antifreeze) and other toxic chemicals …” The council notes a 13 percent higher death rate for embalmers; in addition, their risk of contracting leukemia is eight times higher than the general public’s, and the risk of contracting ALS and other autoimmune and neurological diseases is three times higher.

The body that presents as land is hurt, too, by our practices: each year burial waste includes the use of 77,000 trees, 1.6 million tons of reinforced concrete for vaults, and enough embalming fluid (4.3 million gallons) to fill over six Olympic-sized swimming pools, according to GBC. Then there’s the chemical leachate of heavy metals, like arsenic from sealants and lead, copper, and zinc from caskets, and atrazine (“banned in Europe, and one of the most widely used herbicides in cemeteries”). The effects of contemporary burial practices refract out, degrading the integrity of the body, wounding those who care for our outsourced dead, imperiling the land meant to receive us, and, as ecosystemic violence will, wrecking the integrity of relationships among all while obscuring the existence of those relationships entirely. Of our resistance to direct return, one friend wrote: “Embalming is damage to the infrastructure. When we eat and are not eaten, we are thieves and the theft is from the system, the whole, the larger communion. Only humans are foolish enough to believe we should or even can launder our energy into crypts or caskets that will preserve us.”

Why else is it hard to imagine death—or life, for that matter—ecosystemically? We are made queasy by the biologics, yes. And we have been long-adapted to the charge of Dominion. But most essentially, at core and at large, we are exiled from the systems to which we belong. And without knowledge of the miraculous systems, we cannot enter—or love or preserve them. These days, so many of us come to know systems first by way of their ruin—and without prior knowledge, connection, or relationship, the losses come forth as reportage; grim facts on the demise of once-perfect patterns.

Consider the lives and habitats of snow hares in Glacier National Park in Montana. Until I read Christopher White’s The Melting World, I knew nothing of their realm. The balanced system goes like this: as fall comes on and the days begin to shorten, the hare’s meadow-brown fur, triggered by changes in the length of daylight, whitens up to meet the snow. Hold that now, just for a moment: body of hare and body of land, and the likeness between. As a result of rising temperatures though, snowfall comes on much later now, and the hare is exposed too soon, its white winter coat making it vulnerable and, so, overhunted—a change that affects the lynx as well, whose primary prey is the hare. Pushed to move to higher ground but without new corridors for migration (the land dense now with fast-growing pines that easily adapt to warmth), the lynx are vanishing, too.

This isn’t news to those who study the behaviors of snow hare and lynx, or the lives of meadows and languages of trees, but hearing about it for the first time?—how quickly a vast and astonishingly functioning system is summed up, framed off, and presented by way of the effects of its ruin. We have to read backwards for the interconnectedness, a state of being now steeply foreshortened. There’s hardly time to sit with our awe, one of the ways to alchemize communion and care. Miracle comes tethered to miracle’s ruin.

Some facts are also holy: you get to live on in the lives of others.

“Green” burial—what once was simply the unimpeded return of the body to the ground—will not save us, or much of anything. The recent October 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes stunningly clear that there isn’t much outright saving left to do. There’s mitigating, adapting, some ameliorating, the possible but as-yet-undeveloped technologies—viable if we undertake radical change on a global scale pretty much right this minute. “Resilience” and “innovation” get much play. The “small gestures” argument—everyone doing their part as habit and practice—yes, that too. We must. All of us. Now. And so many around the world are not settling into defeat. But if the necessary measures are possible-but-unlikely, if we consider that we are creatures who, from way back, knew-but-did-not-heed—then we need to ask why else we might bother with small moves, with the likes of say, green burial?

Because some facts are also holy: you get to live on in the lives of others.

Because if you assent to your part in the cycle, the transformations right here below your feet, then you get to live on in the lives of others.

Because contrary to the jittery existentialist notion—that meaning is contingent on one’s freedom to create it at will—the biologics of everlastingness are already in place and exist on their own with or without your consent. Such nuanced, untapped abundances can be tricky to locate, much less love—quiet, slow, largely out of sight, impossible to sum up or boil down. As William Carlos Williams wrote,

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.1

And what is found there, in the cascades and chains, transpirations and respirations, efficiencies and enzymatics, satisfactions circulating (scent of cold, mossed bark in spring, wet marsh rot, river-shine pinking stones)—in all those formal, lyrical arrangements around, above, below us? Actual roots for the unrooted, the disaffected, those without community, the lost, or exiled from usefulness. These particular roots require no assent to realms unseen (though some practice of gratitude is in order), only a sidling up to all you have used, and that in turn will make use of you. What we’ve been searching for all along—a way to be-with, be of use and remembered—all that is right here.

And where might that be?

A “cemetery” might now be a forest of kin. Consider the Capsula Mundi, a design project wherein, upon death, the body is folded up very compactly and laid in a “capsula,” a biodegradable, egg-shaped pod (“an ancient and perfect form,” say the designers), then planted in the earth and topped with a young tree. A place where decay emancipates growth, penetralia sinks its green roots in.

At first, I was startled by the website’s opening image—arms hugging a tree with “Hi Grandma” scrolling across the screen—which seemed Hallmarky, irreverent, and dumbed down, insistent on human primacy; but while the photo shows none of the grace, integration, and practices of indigenous forms of deep kinship, still, the inclination is there. (Note to self: in desperate times, try tamping your aesthetic angst and word choice austerities; locate the core rightness and, god help us, humor in the imperfectly stated.)

To pass into the hands of the least of us (for care we say “hands,” but I really mean “mouths”) is to acknowledge relationships of reciprocal worth—even as we continue to make the grounds for those relationships wildly inhospitable. In place of slogans that deny interdependence, that justify means-to-ends, and plain meanness—nature red in tooth and claw, law of the jungle, survival of fittest—imagine instead a working system. Routes in and out, equilibriums adjusting, hungers assigned to sweetmeat and gristle, breakdowns and undoings, bluebottles then greens at their right-timed work: tender, blackened, leavened us. To come to see you have a place—no leap of faith needed, no assent to unknowns—requires attention, that uniquely human offering. Which if steadied and sustained might make of this given ground, a home.

- “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower,” by William Carlos Williams, from The Collected Poems: Volume II, 1939-1962, copyright ©1955 by William Carlos Williams. Reprinted by permission from New Directions Publishing Corp.