David George Haskell is a biologist and professor of biology and environmental studies at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. His books include The Songs of Trees: Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors, winner of the 2020 Iris Book Award and the 2018 John Burroughs Medal; The Forest Unseen: A Year’s Watch in Nature, winner of the National Academies’ Best Book Award for 2013, finalist for the 2013 Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction, winner of the 2013 Reed Environmental Writing Award, and winner of the 2012 National Outdoor Book Award for Natural History Literature; Sounds Wild and Broken: Sonic Marvels, Evolution’s Creativity, and the Crisis of Sensory Extinction, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize; and the forthcoming book How Flowers Made Our World.

Katherine Lehman, violinist, is an arts leader and educator creating a new vision for music in American communities. Currently Executive Director of the Boulder Philharmonic, her innovative Hearing Boulder initiative leverages great artistry to empower, inspire, and heal by first listening to our people and our planet. Lehman has led NEA-supported commissions and earned an ASCAP Adventurous Programming Award. Formerly, Lehman served as Professor of Violin at the University of the South, Director of the Sewanee Summer Music Festival, and Director of the Sewanee Performing Arts Series. Performing extensively as a soloist, chamber musician, and recording artist on Nashville’s Music Row, she appears on hundreds of albums, films, and videogame scores. Lehman studied at the Eastman School of Music and Northwestern University. She performs on an 1874 J.B. Vuillaume.

Studio Airport, founded by Bram Broerse and Maurits Wouters, is an interdisciplinary design studio that ventures out into the cultural ether to forage for anomalies, creating work that spans art, culture, science, and ecology. In addition to Emergence Magazine, their creative partners include the Design Museum, See All This Art Magazine, Slowness, Normal Phenomena of Life, and Sapiens Magazine. They serve as master tutors at the Design Academy Eindhoven and were recognized as European Agency of the Year 2024 by the EDA.

David G. Haskell invites us into the unique and sometimes surprising aromas of eleven different species of trees.

I. American Basswood

Harlem, New York City

Vintage: 1908

We crack the windows on summer’s first warm days. I taste diesel smoke, acid and oily. The fumes rise from the bus stop directly under the fourth-floor apartment. The odor sinks to my gut, a thin sheen. The ice-cream truck across the street runs its generator all day, into the night. Its exhalations cling high in my nose, a bitter sinus-cloud. Then, one morning in June, honey and wild rose reach through the window. Combustion odors flee. A hint of lemon rind rolls close behind.

All week, the street air is drunk on basswood flowers. The knots inside us loosen.

The tree is a giant, rooted in a roadside park across four lanes of gunning engines from our window. From tens of thousands of tiny creamy mouths, the tree exhales its spell. Herbalists and biochemists agree: tinctures and teas made from the flowers or leaves of basswood and its sibling, linden, soothe our harried nerves. The tree lays a calming green hand on anxiety’s brow, tranquilizes the neural pathways of pain, and weaves its aromas into the fractures in our central nervous systems. We breathe the tree, no longer dis-eased.

The flowers fall later in June, and the city reasserts its grip on our senses, a tight haze. But, now we are joined to the tree by the lingering imprint of its aroma. Years later, I feel the tree’s touch resting inside me.

II. Green Ash

Boulder, Colorado

Vintage: 1980

I kneel at the pile of fresh wood chips and scoop a double handful to my nose. A wet-green aroma: chopped lettuce and asparagus, backed by a whisper of tannin. Four hours ago, an ash tree stood here. Now, its trunk and limbs are gone, hauled off by the arborist’s crew. A stump grinder’s spinning maw turned the trunk’s base and the upper roots into a heap of pulverized sawdust. A circle of golden leaves on the ground marks the extent of the canopy, an imprint that will be raked away by evening.

I lower my head and inhale again. Chopped fennel, a hint of mushroomy soil. The odor is intense, like diving in, mouth open. All at once, years of slowly accumulated aromas in ash wood are liberated into the air.

Further down this street, three other ash trees came down today. Across North America, hundreds of millions of ash trees are gone, an erasure caused by one species of beetle, the emerald ash borer. This beetle somehow found its way from East Asia to southeastern Michigan, and, in a little over a decade, spread and expunged from city and forest alike one of America’s most common trees. The next morning, I return. The odor is already muted. I smell churned soil and a hint of yesterday’s green.

The gentle aroma of ash leaves, a complement to the sharpness of oak and the spice of pine, no longer threads through this neighborhood. These aromatic chemicals were phrases in the trees’ conversations with one another. The trees’ compatriots—native insects, fungi, and microbes—used the aromas to find their homes. In this loss of sensory experience, this impoverishment of ecological aesthetics, our bodies understand the extinction of biological connection, vitality, and possibility.

III. Gin and Tonic

Vintage: 1870s

In your hand: a highball glass, beaded with cool moisture.

In your nose: the aromatic embodiment of globalized trade. The spikey, herbal odor of European juniper berries. A tang of lime juice from a tree descended from wild progenitors in the foothills of the Himalayas. Bitter quinine, from the bark of the South American cinchona tree, spritzed into your nostrils by the pop of sparkling tonic water.

Your drink was mixed by the hand of colonialism. For centuries, the astringent oils of juniper berries flavored and preserved the meats, beers, and spirits of Northern Europe. Gin, distilled from grain but flavored with juniper, is named for the tree—genevre, the Old French word for juniper. By the eighteenth century in Britain, gin was cheaper and flowed more abundantly than beer. Juniper seeped to other continents as colonists carried their tastes across the seas.

In the tropics, gin soon found a sylvan companion. An infusion made from the bark of cinchona trees eases malarial fevers. After Jesuit priests documented the bark’s effectiveness in the seventeenth century, likely inspired by the medicinal uses developed by Indigenous people, Spanish colonists in South America monopolized trade in the bark. Cascarilleros, “bark workers,” cut trees, then stripped and dried the bark. Demand for the bark surged in the following two centuries as colonial expansion continued, decimating wild cinchona populations. Spurred by scarcity, British, French, and Dutch botanists eventually sent cinchona seeds to Europe, then established plantations in their Asian colonies, especially in Java. Chemists isolated the active compound—quinine—and these plantations fed an industrialized supply chain. By the early twentieth century, 90 percent of global trade in quinine from cinchona came from Dutch colonial farms in Asia.

But quinine alone is a bitter draft. So, British colonists in India dissolved their medicine in tonic water and stirred in some gin. A dash of sugar and a wedge of lime added flavor and aroma, especially when the lime’s skin was slightly twisted to release its store of oils. A colonial troika of trees: juniper, cinchona, and lime.

Take a sip, feel the aroma and taste of three continents converge.

Gin and tonic manifest for our nose and palate the global tangle of trees in our lives. We sit on furniture assembled from unknown forests across the world, read paper sourced from plantations thousands of miles away, live in buildings made from dozens of trees reconfigured into plywood and lumber, and dine on fruits and oils brought to us by modern colonial trade networks.

The highball glass, beaded with cold sweat, is a mirror.

IV. Ginkgo

Sewanee, Tennessee

Vintage: circa 1930

Ugh! Gak! Disgust erupts as college students pass under the tree’s spreading branches. Their feet dance jigs, twitching up and skipping sideways. A few take leaping strides in their haste to escape. A profusion of stinking apricot-like fruits circle the ground under the tree. Their presence has animated the usual nonchalance of walkers between dorm and dining hall.

The tree, a giant ginkgo planted in the early twentieth century, holds up a middle finger to college quadrangle aesthetics. I love it for its defiance. Here is messy fecundity on full display, an affront to the mown, suppressed conformity of the tidy campus lawns. These grasses are forced into the illusion of perpetual sexless youth by fertilizers and spinning blades. No profligate reproduction on display from them. Even the other trees on the quadrangle are chosen for their demure characters, species whose flowers and fruit leave no reminders on lawns and paths of aromatic, fleshy sex.

The odors: Rancid butter. Oily beards of billy goats turned rank by their braggart streams of piss. Vomit. Hundreds of mushy silvery-orange blobs litter the ground under the ginkgo tree. Their emanations combine to make a wall of icky smell, the aromas of overripeness and decay. The odor comes mostly from butyric and hexanoic acids, the same molecules released when butter and cheese oils decay, when fats in animal oils fester, and when we puke the hidden fermentations of our guts. No wonder the students exclaimed and pranced as they walked to breakfast.

The ginkgo’s aromas delight me not only for their discomforting effect on the present, but because they tie my senses directly to life’s deep history. Ginkgo has lived nearly unchanged for about two hundred million years. A living fossil, the tree evolved before the giant supercontinent Pangaea broke apart. The tree graced forests worldwide in the Jurassic and Cretaceous. From the end of the Cretaceous, sixty-five million years ago, to the present, wild populations declined then disappeared, first from the southern hemisphere then gradually across the northern continents. By about a million years ago, ginkgo was extinct worldwide, except in an enclave in southwestern China.

The aromas of a ginkgo are a reminder of its relationships with long-extinct animals. We don’t know exactly which species dispersed the ginkgo’s seeds in ages past, but dinosaurs with a taste for putrefaction, along with ancient mammals and birds, likely swallowed the smelly, pulpy surrounds of the seeds, distributing the ginkgo’s progeny in their dung. Today, ginkgo fruits attract scavenging leopard cats, palm civets, and raccoon dogs in the temperate forests of Asia. But the vast majority of ginkgos are now propagated by people, either from cuttings or seeds planted in nurseries. We’ve taken over the work of the dinosaurs, but the aroma is bereft: its function as an attractor for animals largely disappeared in this new world. Instead, humans shun odoriferous female trees, culling young trees in the nursery or grafting male branches onto rootstock.

As I walk under the tree, I think, too, of the melted stone and metal of Hiroshima. The first and often the only life to grow back after the nuclear blast were ginkgo trees at the temples. Deep roots and physiological resilience carried the trees through a calamity that killed all else. Ginkgo’s ability to withstand assault also accounts for the tree’s presence on polluted city streets. The tree weathers the chemical and physical assaults of urban life and is a favorite of urban horticulturalists. Ginkgo is now mostly a species of the street, its roots sunk into sidewalk openings in Tokyo, New York, and Beijing.

As I feel the mucilage of ginkgo fruits underfoot and the odor of rot in my nose, my imagination is drawn into other places and times. Ginkgo trees’ stink is more than an amusing foil for the prissiness of campus plantings. In my nose is the aroma of life’s persistence, a pungent reminder that a tree’s generative power can prevail amid the convulsions of mass extinctions, the breakup of continents, the noxious air and soil of crowded cities, and the annihilation of nuclear war.

I stop under the tree, inhale deeply, and embrace the putrid glory of life.

V. Ponderosa Pine

Bear Canyon, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Vintage: various, circa 1700 to 2000

We are cocooned in the sun-warmed aroma of a bakery. As we stroll up the canyon’s gentle slope, pine duff softens our footfall. All around, the flakey amber bark of ponderosa trees seeps its vanilla and butter confection into the summer air. There is no breeze today, so we swim through a mist of delight. Ponderosa is famed for its gorgeous scents, yet this canyon’s welcome seems to surpass all others: glowing, rich, and full of ease.

Ponderosa is a delight not only for the succulence and abundance of its bouquet, but for how its aroma reveals the individuality of each tree. Each trunk has its odor. We learn, through our noses, a general truth about trees. Like us, they have their dispositions and histories. Mostly, these variations are hard for human senses to grasp. But ponderosa pine, unlike most trees, does not tuck away its inner life. This gives us an excuse to stop, wrap an arm around the trees, and press our noses to their bark. What, tree, is your name?

The blend of a dozen volatile chemicals—the monoterpenes—gives each tree its aromatic signature. Monoterpenes are variations on the same molecular theme, ten carbon atoms stitched together in rings and strings. Small rearrangements of these patterns yield molecules with different aromas. Pinene has the harsh, astringent smell of turpentine. Limonene is the zest of lemon rind. Myrcene is bruised thyme, pleasant and calm. Carene evokes fir needles and sweet resin, more mellow than pinene. These and dozens more variants of carbon origami form much of the aerial language of plants. With so many constituent parts, every breath of odor from leaf and trunk can encode thousands of different meanings and identities.

An old tree, its trunk twice the girth of most in the canyon, is unlike all the other ponderosas here. No vanilla smell at all. Instead, cedar, with a tang of bitter turpentine. The elder’s trunk bleeds resin from hundreds of insect-inflicted holes. No scent of ease, just the sharp bite of chemicals deployed by a tree fighting for its life. Lab experiments confirm that stressed or wounded ponderosas tilt their resin away from gentle limonene and toward pinene. This may help deter insects, but also signals the news of distress to neighboring plants.

Other trees in the canyon are united by their ambrosial aroma, but nonetheless each has its voice. On the drier, hotter slopes the trees have overtones of bourbon. These hints of darkness are scarce here, more typical of trees further north, in the Colorado Front Range. The largest trees, their bark often split by scars of long-ago lightning strikes, have odors edged with hints of burned brown sugar and caramel. Or are my eyes confounding my nose, making me smell the fire? Younger trees, especially those in the well-watered base of the canyon, release a guileless butterscotch, with no hint of trouble or edge. From my sniffing of trees through the year, I know that these are the aromas of the growing season. In winter, flows of resin slow and the cold restrains the liveliness of aromatic molecules. But even in the snow, each tree has its character. In January, some ponderosas are, to my nose, silent, but others sing their aromas to the chilly sun.

The odor of each individual reveals both its pedigree and the nature of its local environment. Parent trees with lemony resin—more common in ponderosa from the Pacific side of the Rockies—pass along their chemical proclivities to their offspring, for example. Each sapling also experiences a unique combination of soil, water, tree neighbors, browsing mammals, and tunneling insects. Tree personality is a melding of heredity and experience.

What we humans experience as aromas, trees use to communicate and defend. Their airborne molecules connect trees, delivering precise messages about forest news. Where are the hungry mandibles of the enemy? Reply to me in our dialect. The right mix of chemicals is interpretable only to trees with kindred sap. In this way, clans whisper to one another through the forest air. The ancient society of trees is conspiratorial as well as collaborative, a fruitful tension. Our dullard noses and understanding are as yet able to grasp only the edges of these conversations.

The same molecules sicken and kill insects, severing or befuddling the links between their nerve cells. If a tree senses insects chewing into its trunk or leaves, or receives an alert from a neighbor about such attacks, it boosts its production of the more insecticidal chemicals. The predators of tree-chewing insects—carnivorous and parasitic beetles and wasps—sniff the air for these defensive aromas of trees and use them to home in on their prey. The chemicals signal to mammalian noses, too. Deer, porcupines, and Abert’s squirrels all prefer to browse on less aromatic trees.

Ponderosa’s mortal enemy, bark beetles, add a cunning twist. They pilfer tree monoterpenes and tweak their chemical structures. The result is a powerful pheromone. The refashioned molecule, blended with other beetle aromas, summons a mob of other beetles. They cluster on an individual tree and launch a mass attack. The bark beetles turn the tree’s shield into a spear.

The earthbound drama mediated by pine tree aromas drifts upward and changes the sky. Yearly across the globe, trees send ten trillion kilograms of aromatic molecules to the air. This great heavenward exhalation of trees primes the sky for rain. Tree aromas become the seeds around which raindrops first gather. The sky is partly made of forest.

The delight I feel in the ponderosa’s aromas joins me to the communicative heart of the forest. Trees confide in one another. Insects eavesdrop and concoct. Earth and sky converse.

VI. Pine Tree Hanging from the Rearview Mirror

Vintage: patented 1954

The cardboard tree swings violently as we take the corner. The swinging motion looses pine and lemon scent from between fibers of compressed cellulose. A gust of forest air, right here in the car’s interior.

Outside, a traffic jam. Gasoline byproducts and nitrogen oxides stream from tailpipes. When sunlight hits the fumes, the pollutants seethe and react, making ozone. The car interior is now a chemistry experiment: monoterpenes originally from trees blend with ozone, all held inside an enclosed space. When chemists replicate the experiment in the lab, the reactions of “air freshener” chemicals with ozone yield a mist of invisible particles and organic gases. The fine particles are a hazard not only to the lungs, but to other tissues of the body. So, too, are the gases born in this experiment, acetone, formaldehyde, acrolein, and acetaldehyde.

The Anthropocene turns the healthful breath of a forest into something more troubled and ambiguous. Trees scrub some pollutants from the air and, when planted in a city, can reduce pollution. But on days when ozone is high and trees are pouring their aromas to the sky, the air is hazed with particulate pollution from the collision of tree breath and burned fossil fuel. Inside the car, we trap this unfortunate reaction and envelop ourselves in its products.

The aroma-tree on the rearview mirror is like an incense censer dangling from a priest’s hands. It swings over us as we drive, delivering the dubious benediction of modernity.

VII. Nothofagus Beech

Queensland, Australia

Vintage: unknown, likely many centuries

A giant limb has snapped from the trunk, exposing smooth laminations of wood in the torn stub. At its center, the branch is maroon, as if soaked by red wine. Wrapped around this core are layers of cream-colored wood, smooth to the touch where the violence of the fall has peeled them apart. I lift this striking two-toned scar to my nose. I’m stunned by the gentle aroma. Despite the damp wind chilling me, the tree conveys warmth and calm. Buttery pastry fresh from the oven. The aroma of sun on ripe apples. But these impressions quickly fade. The limb came down just minutes ago, and already the wood is surrendering its inner life to the breeze.

These Nothofagus beeches are descendants of the forests of Gondwanaland. Their relatives live all across the southern hemisphere, from Chile to New Zealand. They were common in Antarctica before it froze. Here, at the easternmost edge of Australia, they’ve clung to the rim of an extinct volcano for centuries, each individual cycling through successive trunks. When old stems fall, new ones resprout from the living roots. They are so old that the slow erosion of the ground around them has left each tree on root stilts a meter high. The population persists on a strip of land hardly wider than a couple of trees’ branch span. The trees live within a thin sliver of possibility: winds with enough moisture, temperatures just right. In their thriving, they bring to our senses the richness of Gondwanan rainforests.

I heft the limb to the side of the trail and return to the earthy aroma that enfolds the rest of this huge, gnarled tree. The fulsome odor of wet peat. A hint of tannic decay. The sharpness of fern fronds. Walking in the forest here is like swimming through a moss world. I’m a springtail, a tardigrade, a nematode, miniaturized by the huge trees, enveloped in moss. Every trunk and branch is swaddled. Fern stems snake through the verdant thickets on branches, poking their paddle-like leaves above the tangle. It’s likely that the water-saturated weight of this lush wrap is partly what broke the limb at my feet. Every tree branch is a sky-lake and forceful gusts push wood beyond its limits.

On this isolated mountain ridge, these ancient trees make their own rain. Wind blowing from lowland eucalyptus forests, cattle pastures, and Pacific shores cools as it swoops up the escarpment of the volcanic caldera. This sudden chill causes water vapor to condense. Dense clouds stream through the forest, even when the rest of the landscape lies under blue skies. The mop of moss and the dense thatch of tree leaves intercept the river of fog. Droplets land and accumulate. Moss and ferns hold on to some of their harvest, supping on the sky. The rest falls, ringing the ground below with moisture: every tree is a rain-maker. The ground between these halos is dusty dry.

This rainforest’s aroma is that of the rocky seashore, without the salty bite. A fecund exultation at the meeting place of water, sky, and life. This is an ancient triumph, started by the first algae and land plants on Paleozoic shores and carried to the present by every water-sucking root and moisture-quickened leaf. Here, the celebration reaches a zenith, water and plant life flowing into one another, lifting tree giants from the ground, soaking the air in the odors of green.

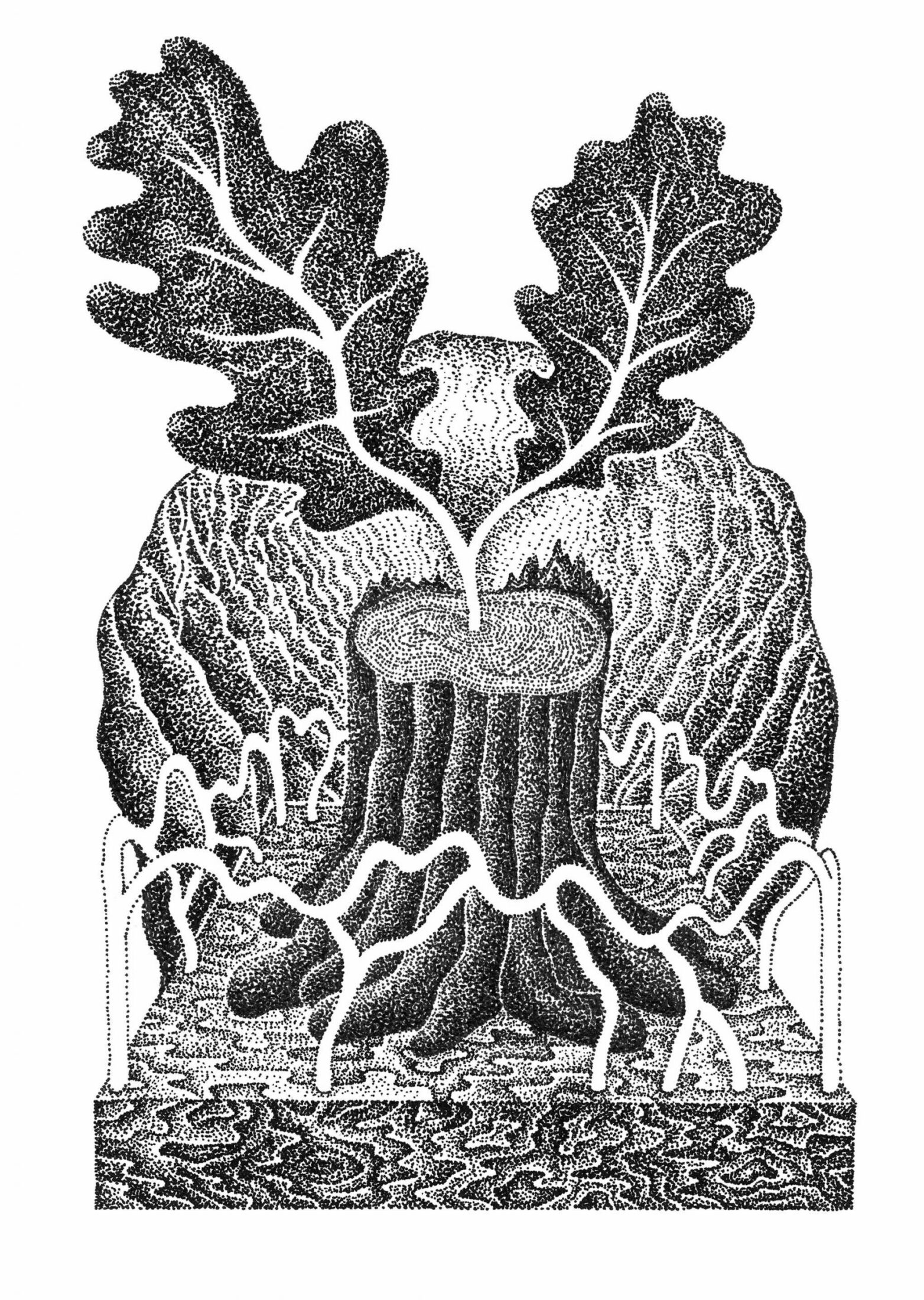

VIII. White Oak

Sewanee, Tennessee

Vintage: 1830

I am stacking split firewood by ear. When a wedge hits a slot just right, it clacks with a taut, deep tone. No shake, all sides snug as the tidy wall builds. Higher tones, double knocks, or clumsy scrapes tell of a poor fit, one that risks toppling the stack. So, I twist or flip the offender, then turn and pull another piece from the unstacked pile.

I feel the reassuring weight of fuelwood in my shoulders. Each piece of wood is an ingot of sunlight, a store of life-giving heat. My muscles understand this meaning. My nose does, too. The splitting and slinging of oak have raised a mist of woody aroma. Mostly sharp, sweet tannin, a dark tea spiced with cloves. Bitter and hot. Heartwood is tart enough to sting my nostrils, a punch from the tree’s defense against inner rot. At the trunk’s edges, the lighter wood has overtones of coconut, of singed sugar.

The white oak died this spring. Its afterlife could have nourished fungi and many animals for decades, but the danger of falling limbs condemned it to removal from its place on the verge. It likely germinated before the road was built, on a forest slope, but died alongside a town road. I salvaged the wood from the municipal burn pile, a pit dug into the sandstone. If the tree is to burn, it will do so through my stove.

White oak was a lucky find at the dump. I’m bathed in the aroma of wine and whiskey barrels. Had this year’s haul been red oak, I’d be smelling vinegar and old engine oil. Tolerable, but not a delight. Had I found pin oak, I’d have left it. Split, it reeks of tomcat urine, a smell that fades only after a couple of years of seasoning. Piss oak is its local name. Squirrels concur with my judgment, preferring acorns from the less astringent white oaks over red oak with its heavy investment in bitter defenses.

My oak-sniffing is amateur, an apprentice’s coarse taxonomy. Vintners and whiskey makers understand the nuances of a single species. No piss oaks for them, just white oaks from America or Europe. The barrel staves ease their woody songs into the liquor. Tight-grained white oak from Minnesota takes its time, its bitter tannins subtle and rounded. Virginia’s trees are more open-pored and eager to share their spice. European oaks evoke more hazel and dark smoke. All this aromatic subtlety is adjusted by flame on the empty barrels’ interiors before filling: a mere lick yields spiciness, a good toast brings vanilla, and a heavy burn roasted coffee. The barrel’s terroir and treatment are as much a part of drinks’ aromas and flavors as the grapes and grain.

We’re not alone in savoring plant tannins and their aromatic chemical allies. The diet of most herbivores, especially those that browse on wood and leaves, is a feast of these molecules. Every plant species has its own aroma and taste, and every leaf on the plant has its own signature, with the concentration of tannins often increasing as the leaves age. Watch a deer or goat use its lips and tongue: they sift through vegetation, plucking their favorites with great precision. Discerning palates and noses benefit the animals. At low doses, tannins and other tasty plant chemicals are antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidative. Animals with stomach upsets will seek out tannic food, self-medicating to purge intestinal parasites.

But tannins are there to defend the plant. Without countermeasures from herbivores, these bitter chemicals bind proteins and disrupt digestion. And so, browsing animals have saliva tuned to the tannic mélange of their favorite foods. Moose saliva subdues the tannins in aspen and birch, beaver saliva is adapted to willow, mouse to acorn, mule deer to their diverse diet of trees, howler monkeys to tropical leaves, and black bear saliva works on all kinds of tannins, as befits an omnivore. Human salivary proteins, like the bears’, are primed to meet a wide variety of plants. Our saliva is tannin-ready all year, not just seasonally as in many other species.

Oak firewood, red wine, well-steeped tea. We are ready for winter, our noses leading us to the human ecological niche.

IX. Bay Laurel

Paris, France

Vintage: 1980

Smell is the most ancient of senses. Before life evolved eyes and ears, cells were conversing in the language of molecules. Cell membranes bristled with receptors, waiting for arriving signals from other cells both near and far. This is communication by physical messenger, a molecule from one being traveling to another, blurring the edges of individuality. And so it is today in our noses. To smell a tree is to know that a tiny part of another being has entered and clasped us.

Smell is also the sense most directly connected to memory and emotion. When an aroma arrives at our nose, nerves signal directly to the brain’s centers of emotional memory and learning. Odor bypasses the processing centers that mediate all other senses. Aroma arrives in our bodies first as bodily remembrance and affect. Our brains later added a veneer of language and conscious perception.

What tree aromas evoke memory and emotion for you? Fir trees and holidays. Cloves and allspice in a hot mug of apple cider. The piney-clean smell of a classroom after the floors have been scrubbed. The dusty sting of cedar wood shavings from a sharpened pencil. A haze of leafy aromas in a city park after a summer rain. The floral, waxy smell of date confectionary. These memories, different for each one of us, reveal the nature of our childhoods and early lives. Tree aromas are portals, flying us back into our experience of the culture that raised us.

For me, the bay tree is one such portal. Laurus nobilis, the European cousin of California bay laurel, is a staple of Mediterranean stews and soups. In the mouth, the leaf is bitter and tough. Where I grew up, in France, it is most often used in casseroles for aroma and flavor. We discard the spent leaf before serving. Bay leaf’s smell evokes for me the gentle simmer of a stew whose flavors will mingle for hours, in a pot large enough to feed several people. The aromas rise in the steam. They fill the kitchen and curl into neighboring rooms, carrying the knowledge that food will be here soon, but not yet. Delayed gratification. Then, on the plate, bay reveals the dual nature of smell and taste. The aroma is a vigorous blend of eucalypt and cardamom, with hints of pepper, lavender, and clove. In the mouth, though, bay is more reticent, letting other flavoring plants—thyme and rosemary, especially—dominate the conversation with vegetable and meat. Bay lives in the air and nose, leaving only a slight impression on the tongue.

Warm kitchen, good food, family. As with other aromatic memories, the bay leaf doesn’t just suggest these associations to me. It is them. Its aroma plunges directly into deep memory, activating from within. If you mapped all the people who share this memory of bay, you’d draw the rough contour of Mediterranean cooking and its diaspora around the world. But this would be a crude map of the link between bay and human memory. For many Italians, pasta sauces or risottos, not stews, would be bay’s companion in memory. For anyone raised with Syrian Aleppo soap, bay would be the aroma of bath time.

Tree aromas are guides back into wordless memory. And these memories keep forming. What trees from the present moment can we graft into our memories or those of youngsters around us?

X. Woodsmoke

Forests worldwide

Vintage: today

The smoke from wood fires made us. It may also be our undoing.

A million years ago, small bands of walking apes gathered at campfires inside caves in southern Africa. For these ancestors of modern humans, the smell of smoke was the aroma of home. In the millennia that followed, burning wood was an evolutionary catalyst. Flames hardened spears, flaked stone tools, and cooked food, nourishing and protecting our ancestors. Fire allowed our brains and technologies to expand and flourish. Fire also catalyzed culture. By drawing us into close circles, the campfire knit together our minds and emotions, intensifying and deepening human social interactions. To this day, when we gather at the fire, our blood pressure drops and conversation turns to the realm of the imagination, to stories and possibilities. Human society was born around wood flames.

No wonder, then, when we gather for ritual or celebration, we light a wood fire. The aroma, sounds, and hues of burning wood promise pleasure in meeting others and unity in the community. When the fire is fueled by modern natural gas or compressed charcoal, we buy aromas in bags of wood chips, flavors from jars of smoky seasoning, and flame-mimicking lightbulbs, artifices aimed at recreating the ancestral sensory experience. We’re an unusual mammal, loving fire and going out of our way to bring it into our homes. Most others flee its dangers.

But wood smoke also maims, kills, and distorts. A waft of smoke after a day’s work might initially smell of ease and conviviality. The same smoke inhaled over weeks and years wreaks havoc inside us.

At least four hundred different chemicals combine in wood smoke, most of them harmful: carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, benzene, and hundreds of irritant, neurotoxic, and carcinogenic molecules. Wood smoke also hazes the air with billions of microscopic flecks of partly burned wood. This particulate pollution damages lungs and enters our blood, inflaming us, literally, from within.

Those who cook over open fires are at most risk. But this smoke from domestic burning of wood is now joined by the worldwide conflagration of forests. From Southeast Asia to the Amazon, from California to New South Wales, from Siberia to Africa, the world’s forests are ablaze at a scale that rivals the fieriest times in Earth’s prehistory. The pall from the largest fires covers many countries.

Peppery sting in sinuses. An oily, metallic feel in the mouth. The inhale is insufficient, as if acrid haze displaced the oxygen. Lungs clench. Inescapable. The aroma, taste, and bodily invasion of wood smoke assails us. After fires burned through millennia-old peat forests in Indonesia, one hundred thousand people died as a result of smoke. In California, heart attacks and strokes surge during large burns. Prolonged inhalation of wood smoke ravages our heart and blood vessels, kills infants, and stunts lungs.

The weight of knowing what we’re breathing compounds the harm. The forests, now turned to gas and haze, were once our source of life: water, food, the ten thousand creatures, spirit, home, and solace. We pyre what would have been our future. Dark smoke for our spirits and psyches.

Human ancestors thrived by learning to control fire. They found ways to partner with flames, opening new technological and social possibilities. We are all descendants of their canny skill. Now, we have lost control. Smoke teaches us that from the inside.

And so, what next?

Wood smoke has always called us into community, opening human possibility. The modern crisis of forest burning does the same, but on a scale unknown to all previous peoples. It is no longer a campfire or hearth calling us, but the ancient forests themselves, as they blaze and die: Gather. Imagine. Act.

XI. Olive Oil

Hills of the Eastern Mediterranean

Vintage: circa 6000 BCE

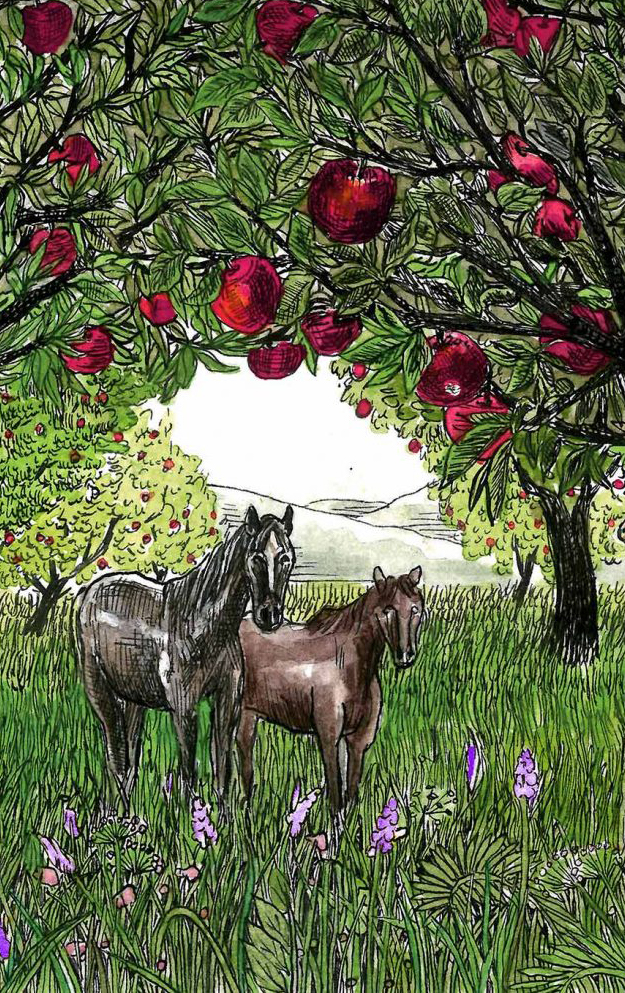

Trees send their aromatic chemical messages to neighboring trees, microbes, and insects. We humans are eavesdroppers. The olive tree, though, is different. It intends its aromas for us. Olive trees and people have been linked for eight millennia.

A verdant smell, like springtime grasses and freshly-cut artichoke. Vigorous green. A hint of tart apple. Peppery overtones. An aroma that promises an inner glow of satisfaction, a complement to bread and grain. The olive tree activates my nose, my thoughts, and my body’s wordless needs, speaking directly to me. This is no accident; evolution has carved knowledge of my senses into the olive tree’s genome.

Before humans yoked themselves to the olive, thrushes and other small birds were the dispersers of the trees’ fruits. Beaks gobbled the oily flesh, then wings carried the seeds away from the parent trees. This is a common arrangement. Half of the tree and shrub species in the Mediterranean unite bird hunger and plant reproduction in this way. In tropical forests, 90 percent of woody plants disperse their seeds via animal guts.

As with any parent entrusting its young to others, trees are picky about which species they summon. The shape, aroma, and color of fruits are tuned to the sensory particularity of the trees’ favorite couriers. The form of fruit is a tree’s answer to animal aesthetics. Red fruits attract the eyes of birds. Odors of decay draw mammalian scavengers. Primates are summoned with fruity, sugary aromas. Migrating birds hunger for energy-rich oils and sugars. Humans are no exception. Any tree wishing to tie its fate to ours must beckon to our senses.

After the last Ice Age loosened its grip on Europe, olive trees spread around the Mediterranean basin. There, the trees mingled with a growing human population. Those trees whose aroma and size suited human tastes found willing collaborators. People served these trees, tending and nurturing them, sparing them from the ax. These human-friendly trees had large, oily fruits with a full aroma and low bitterness, unlike the small astringent fruit of ancestral olive. A bird gullet is narrow and its owner judges fruit by eye. Humans, though, are powerfully motivated by unctuous fruity odors. Our nervous systems yearn for this aromatic promise of satiety.

Over time, people deepened the sophistication of their labors on behalf of olive trees. We built irrigation canals and terraces, tilled and cleared the soil, groomed trees with pruning blades, and mastered grafting and transplantation. The reward for those trees whose fruits appealed to human senses was domination of fields and rocky hillsides all around the Mediterranean basin. The reward for humans, too, was abundance. Olives yield more nutrition from the seasonally arid land than any other crop. Without olive trees, Knossos, Carthage, Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome would have been modest villages. Mediterranean culture was, for millennia, founded on reciprocity with olive trees.

Other trees have yoked themselves to our noses and palates. Citrus, apples, coffee, breadfruit, dates, hazel, brazil nut, almond, oil palm, chestnut, and dozens more. But none so completely as the olive. All around the Mediterranean, the boundaries between wild, feral, and domestic trees are blurred, the result of eight millennia of melding between tree reproduction and horticulture. For human culture and the trees on which it depends, there is no boundary. Human society in the region is grafted on tree roots. Religion, art, and culture remember this.

Pull out a dollar bill. There, wrapped around the numerals and clasped in the eagle’s fist are fruits and branches of the olive, cultural descendants of the sacred trees honored in ancient Athens and Rome. The unending plenitude of olive oil is the ecological foundation of the miracle of the Jerusalem Temple, giving us the Festival of Lights. Jesus became the Christ, khrīstós, anointed with olive oil. The light of Allah in the Qur’an is like that of the lamp oil from a blessed olive tree.

Olive oil is not just a metaphor or symbol for the Divine. It is the origin and sustainer of life and goodness.

I bow my head and inhale. Herbs, steeped in light butter. The aromatic sparkle of tomato leaves rubbed between fingers. A touch of bitter cypress. In the heavenly odors of a bowl of olive oil, I understand the trees’ message:

The sacred does not descend upon us from on high. It is an aroma rising from the living Earth, from the fruitful union of soil, humans, and trees.

The Aromas of Trees: Five Practices

In this companion practice, David G. Haskell invites us into the unique, and sometimes surprising, aromas of eleven different species of trees.