Nick Hunt is a writer, journalist, and storyteller. His books include Outlandish: Walking Europe’s Unlikely Landscapes, Walking the Woods and the Water, Where the Wild Winds Are, The Parakeeting of London, and Red Smoking Mirror. His writing has also appeared in The Guardian, The Irish Times, The Economist, Aeon, New Internationalist, Noema, Literary Review, and Resurgence & Ecologist, among others, and has been included in The Best British Travel Writing of the 21st Century. Nick is a recipient of the Royal Geographical Society Journey of a Lifetime Award and is a contributor and co-director of the Dark Mountain Project.

Sophy Hollington is an illustrator and artist living in Brighton, UK. Much of her commercial work takes the form of relief prints, created using the process of lino-cutting. Her clients include: The New York Times, The New Yorker, Bloomberg Businessweek, Wetransfer, The Wall Street Journal, Penguin, and Stylist Magazine.

Nick Hunt visits Białowieża, Europe’s largest surviving primeval forest, where life and death transform into one another with vigorous entanglement. Here, he traces the history of the European forest, revealing an ongoing battle between light and shadow, clearing and woods.

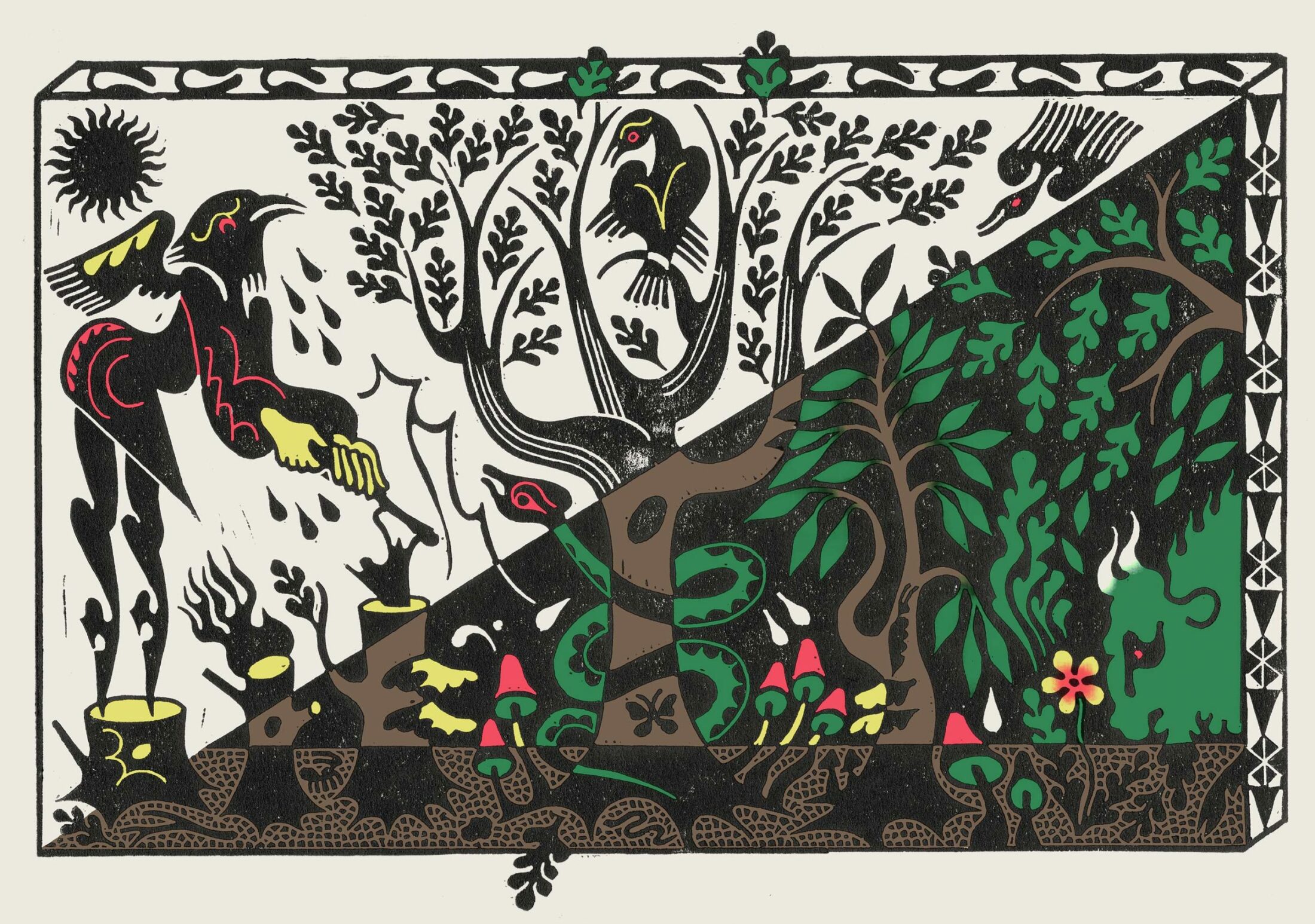

The universe is an oak, unfathomably tall. Its branches stretch to heaven and its roots reach into the underworld, with the mortal realm as its stump. Like ants, we live our lives in the fissures of its bark. At its top sits Perun, god of the sky, fertility, thunderstorms, metal, and war, associated with the axe, whose body takes the form of an eagle perched in its uppermost branches. Around its roots twines Veles, whose body takes the form of a snake, god of the underworld. They are always fighting.

Veles creeps up from the earth to steal the cattle of Perun, slipping in and out of shadows, friendly with the darkness. Perun chases him away with dazzling bolts of lightning that make the world as bright as day, but he never catches him. He never will catch him. Dry weather is the victory of Veles, rain the victory of Perun, and thunderstorms are battles in the eternal war between them. If lightning hits the earth near you, it is probably good luck.

As oak is sacred to Perun, willow is sacred to Veles, and in many ways the trees and their gods act as opposites. Perhaps it is not so much a war as a cosmic balancing. The cool, damp-loving willow contrasts with the dryness of oak, the earth with the sky, down with up, night with day, dark with light, and, ultimately, death with life.

It takes all of these things to make a forest.

We are walking from the pale meadow to the shaded wall of trees, from the light to the dark. It is dawn and the topmost branches are molten with the sun. Frost crunches underfoot. Exactly half a white moon hangs in the clear sky. The woman guiding me is small, grubby, and weatherworn; when I first saw her I thought she had mossy green hair, like some sort of forest sprite, but it is an oversized woolen hat stuck with twigs and leaves. Every so often she stops to scan the wooded hem with binoculars.

What lies ahead is prohibited ground. Without her I cannot enter.

Straddling the border of Poland and Belarus, this protected forest—Białowieża—is Europe’s largest surviving remnant of primeval jungle.

Last night, standing at this spot, I heard wolves howling there.

At the entrance to the forest is a gateway with a shingled roof. The style is a traditional one from the south, says my guide, but its architecture is vaguely familiar for another reason. According to modern myth, the director Stephen Spielberg used it as an inspiration for the gateway to Jurassic Park, the entrance to a primordial world that has vanished from the rest of the earth, filled with ancient forms of life and antediluvian monsters.

Passing beneath that rustic arch and into the gloom of shade, we are stepping into a similar sanctuary. Out of modern Europe and into Eurassic Park.

Straddling the border of Poland and Belarus, this protected forest—Białowieża—is Europe’s largest surviving remnant of primeval jungle.

It is dim beneath the canopy. The track scores straight ahead. At first I see only a monotony of repeating trunks, a view that alters constantly yet is constantly the same. The effect is hypnotic. Apart from the occasional half-fallen limb, diagonally propped, it could be the same hundred meters of woodland caught in a loop.

My eyes are not yet attuned to the intricate relationships, the permutations of the species in their different neighborhoods. I can’t see the trees for the wood. But gradually, through my guide’s eyes, my eyes start zooming in.

It happens in small illuminations as the spotlight of her attention swings from one point to the next, picking and naming details. All I have to do is follow that wandering beam. One moment she is examining a patch of lichen or a beard of moss, and the next she is looking at a trunk that is seemingly suspended in the air, caught in a web of twigs so fine that it looks like levitation. Here a hornbeam and a spruce have wrapped around one another, merging in a grafted kiss, and there the body of a two-foot fungus is rippled like candle wax, powdering the earth below with a snowfall of white spores. In one place she stops to trace the shape of something on the ground: six-bladed white anemones have grown in the absence of a fallen trunk that has completely rotted away, thriving off its nutrients, highlighting its vanished shape like police chalk lines around a corpse.

Wherever I look there is something living growing on something dead.

The story of this forest begins ten thousand years ago, in the vacuum left by the vanishing of ice.

The glaciers of the north shrink back. The permafrost loses its permanence. As the frozen climate warms, the tundra that covers the North European Plain—part of the vast “mammoth steppe” that stretches from Spain to Siberia—undergoes a process of rapid recolonization. The first pioneers to arrive are the tiny windblown seeds of birch, which travel long distances to populate open ground; their pale trunks are like the blueprints of the future forest. Behind them come alder, poplar, and dwarf pine, enriching the soil with fallen leaves. That first wave also brings willow, the tree of Veles.

Perun arrives later as the oaks spread slowly from the south, where they have waited out the Ice Age sheltered by the protective wall of the Alps and Carpathians. With them come hazel, elm, lime, ash, spruce, beech, maple, holly, fir, hornbeam, and other trees, packing out the understory with layers of complexity. By the early Neolithic, the forest is general over northern Europe, reaching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Baltic Sea.

Europe has been colonized not only by trees but by shadow.

What about the people who live through this great shadowing? For thousands of years they have hunted here, following mammoth, deer, and bison across the wide-open steppe, and now—in the space of a few generations—their horizons are filled in. Saplings shoot up everywhere, too fast to be grazed back; in this new landscape of fear, where predators might be hiding behind every fallen bough, the herds cannot linger long and quickly move away. Some people keep following them, to lands beyond the range of trees. But others stay and adapt to life beneath the leaves.

It is as if a great roof has been woven across the continent, blocking out the light of the sky. Part of it must feel like a death.

But new gods peer from between the trunks.

From the darkness of death comes life.

Perun still has a presence here, stretching up towards the sky, deity of metal and war, of vigorous fertility.

She points them out one by one, softly, reverentially: golden saxifrage, a flower with yellow, rounded leaves; red-banded polypore, an orange-crimson fungus; toothwort, a parasite with leaves like sickly purple hands; dead man’s fingers, black fungus that pokes searchingly through damp moss. There are mushrooms in great racks and bergs; lichen ranging from cool grey-green to fluorescent orange; moss so intensely green that, even in this dim light, it appears to burn.

Once, to look closer at one of these things—a cascade of fungal forms spilling from some riven flank—I take a few steps off the permitted track and am instantly reprimanded. Not even a footstep is allowed. I have the sense of breaking a religious prohibition.

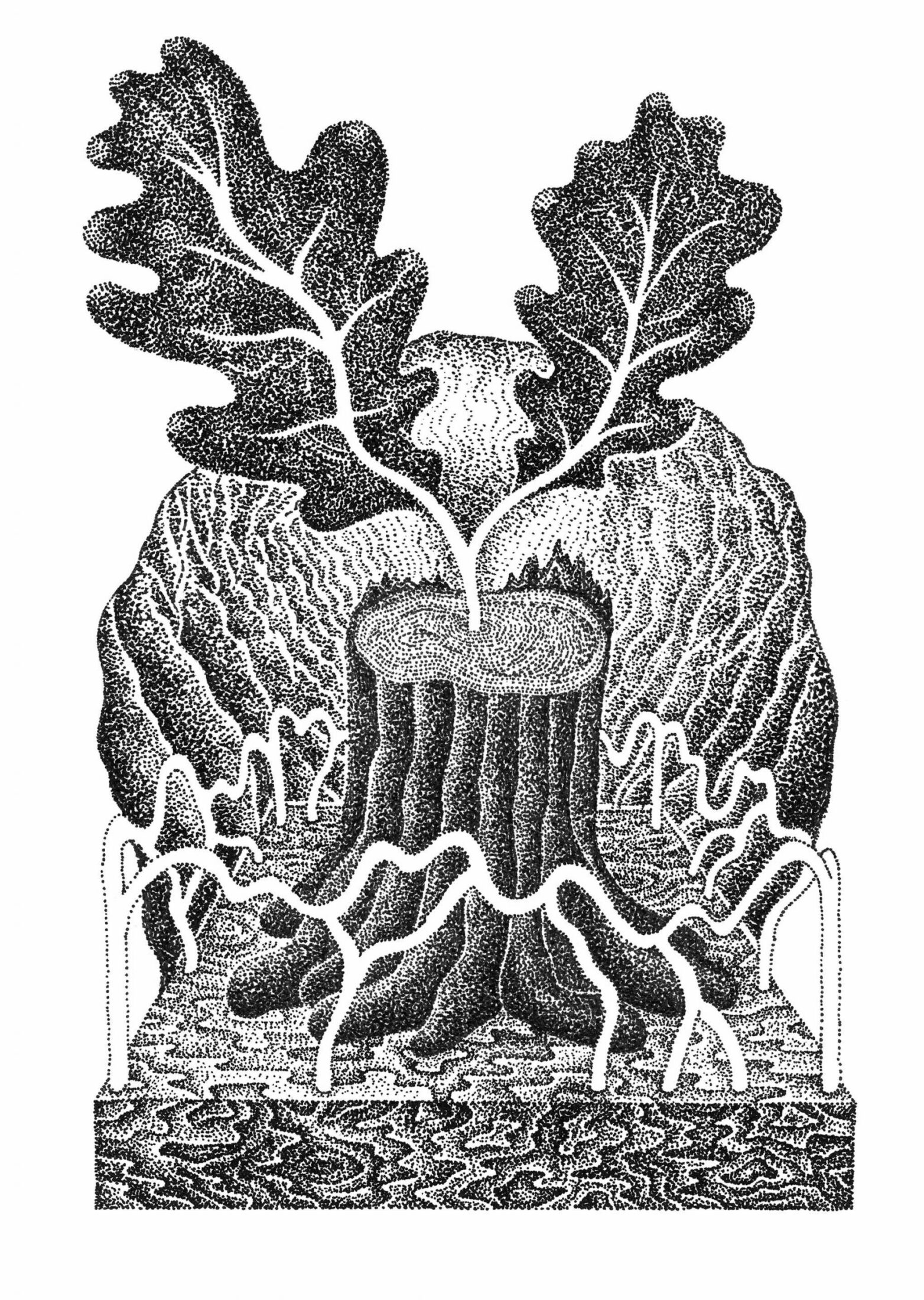

Free from euphemistic “management”—in this most strictly protected part of the forest, not so much as a twig can be taken away—Białowieża contains, by mass, more dead than living wood. My guide explains the process by which one becomes the other. Funguses with ghoulish names like wet rot fungus and jelly rot fungus feed off the lignin and cellulose of which wood is comprised. As their webs of hyphae spread, they create honeycombed labyrinths that provide further access to moisture, bacteria, and insects. The hatching larvae of burrowing beetles create layered galleries, allowing more species in: woodlice, millipedes, slugs, snails, wood wasps, springtails, and earthworms that mine the rotten seams, dying and decomposing in turn, adding sediment to sediment.

Depending on the type of tree, a fallen trunk can take anywhere from several decades to several hundred years to be broken down, during which time it is home, and food, for multiple generations. Eventually, when its physical mass has entirely disappeared, it can be said to no longer exist, but its components do, in innumerable other life-forms.

There are more microbes in a handful of forest soil than there are people on the planet.

The forest does subversive things to conceptions of life and death. We tell ourselves that these states are opposites and absolutes, separated by a line from which there is no crossing back. But in the heart of Białowieża that line is far from clear. The claim that over 50 percent of the forest’s wood is dead appears somewhat meaningless, as much of what we’re walking through is dead and alive at the same time. The dead and the living are constantly in the process of becoming each other.

Civilization’s ancient fear of what the forest represents—the dark, mysterious, tangled woods beyond the village in a fairy tale—surely has its roots in this. A forest is a reminder of death, a living memento mori.

Not far outside the strict reserve is a tourist-frequented grove known as Stara (“Old”) Białowieża. A boardwalk trail leads around the so-called “century oaks” that are venerated as icons of the forest and even of Poland itself. This isn’t only for their age—most are around four hundred years old—but for the history they embody. Each one bears the name of Polish-Lithuanian royalty.

The Jagiełło Oak is named for the forest’s first protector, Władysław II Jagiełło, the last pagan Grand Duke of Lithuania, who, after converting to Christianity, went on to lay the foundations of the future Polish state. The tree fell down in a 1970s storm but still lies as a noble ruin. A nearby signboard reads: “King Władysław Jagiełło initiated the tradition of royal huntings in Białowieża Forest in 1409,” and then—in what is either a typo or a claim of immortality—“Władysław came here in 1926, protecting himself from the plague.” By the Old Zygmunt Oak, a signboard says: “King Zygmunt constituted the law that a death meets the one who would kill an animal in the Royal Forest.” By the Helena Oak, named for the wife of King Aleksander Jagiellończyk: “This lady of hot blood was so unrestrained in her hunting spirit that only the most tenacious could keep up with her.”

If I did not know what they were, I would not even recognize these giants, on first encounter, as oaks. The ancient oaks I am used to meeting—English oaks lining the driveways of grand country estates—are short and squat, knobbled with galls, often lightning-struck or dying from the inside out. These trees, deprived of the roominess they require to spread out wide, launch themselves directly up to heights of thirty or forty meters, practically branchless for most of the trunk and then crowning at canopy level into mazes of enormous limbs. Their girth is formidable, machines pulling water from the earth. Touching the bark of an English oak is like touching noble but corrupted flesh; this, by contrast, feels like laying my hands on living power.

Craning my neck to look up produces an inverse vertigo. It is easy to understand why such trees were worshipped.

These century oaks—with their official designation as “national monuments,” afforded the same status as statues or war memorials—are symbolic reincarnations of the figures they represent, the royal heroes of the past alive in the form of trees. This patriotic overlay has roots deeper than the nation state.

Perun still has a presence here, stretching up towards the sky, deity of metal and war, of vigorous fertility.

How else to describe this place but as a sacred grove?

West of Stara Białowieża is another sacred grove, which is not so widely known. It requires no guide or entrance fee and appears on few maps. One day I walk for many hours to reach it, following a long straight track through the endlessly repeating trees, but at first sight Miejsce Mocy comes as a disappointment.

The site is dominated by a wooden observation deck, a kind of New Age hunting hide for spiritual energy. Here and there moss-covered boulders give the vague impression of a stone circle, if I squint at them hard enough, and in another place people have pushed coins into the cracks of a carved oak post as good luck charms or offerings. Wooden signs in Polish and English—sponsored by Żubr (Bison) beer—give some background information: It is believed that this was once a place of worship for the ancient Slavs, where initiates gathered to “fend off foes and evil powers.” Responsive people, it suggests, “may feel a whole gamut of subtle vibrations, from those purifying the mind and fully relaxing to those shaking one’s balance and causing some dizziness. The arrangement of the stones itself can prevent particularly responsive people from entering inside.”

The circle of stones lets me in without putting up any resistance, and I stand inside, attempting to feel something. All I feel is heat from the sunlight, tiredness from the long walk. I close my eyes and wait. Nothing. Not even the subtlest vibration.

But when I open them again, my eyes have refocused.

There is something unusual about the trees. The nearest oak has four—no, five—separate trunks shooting up from a single massive bole. Another one stands nearby. Turning inside the circle I see another, then another. At first it seems to be the result of very ancient coppicing, but the bifurcations and trifurcations are clearly natural, not manmade but mutated, as if the vigor of their growth cannot help but overspill. Narrow paths crisscross the grove, and following them I come across increasingly bizarre forms. These multiple trunks, rather than the stones, are suggestive of strange energies; did positive radiation cause these thrusts and forkings?

Around one towering double-trunked spruce, two whole trees growing out of one, I find seven china plates. On each plate is an offering: moss, bark, an oak leaf, a spruce cone, earth, a single wrapped boiled sweet, and a guttered candle.

Miejsce Mocy means “Place of Power.” But its former name, according to the sign, was “Devil’s Swamp.”

The forest does subversive things to conceptions of life and death.

The story of the forest’s disappearance is the story of agriculture, that great, world-changing shift from foraging to farming. Starting in the Fertile Crescent around 8000 BC—as the last glaciers are retreating further north—the practice reaches southern Europe five thousand years later. It spreads northward as the forest once did, colonizing the same terrain.

As the darkness leaves the ground, light floods in again.

Trees are cleared by axe and fire for cropland and pastureland, to provide materials and fuel for iron smelting. There have always been scattered patches created by slash-and-burn farming techniques, but as the new culture spreads, these patches merge together. First it is a fragmentation and then a wholesale vanishing. Tree cover declines gradually until two thousand years ago and then plunges rapidly as a tipping point is reached. Civilization follows the axe. By Roman times the south and west of Europe is largely deforested and only the unconquered forests of Germania hold out, beyond the Danube and the Rhine. That mysterious, densely wooded realm, which the Romans call Hercynia, is the symbolic frontier between the civilized and the barbaric.

The tree gods of the ancient Slavs—along with their Germanic, Baltic, and Scandinavian counterparts—retreat into the tangled dark, away from the exposing light. The forest becomes sinister, its Places of Power now Devil’s Swamps.

In the light of the cleared land, a sky god takes their place.

At the heart of the North European Plain, language preserves a memory of this epic deforesting; it is hidden in plain sight, preserved in Poland’s name. “Poland” derives from an eighth-century Slavic tribe called the Polans, which in turn comes from pole, “field” or “cleared land.”

From east to west, the name of the whole country is “The Clearing.” It might as well be applied to the continent itself.

Axe and fire: their destructive powers have always been associated with the worship of Perun, god of metal and lightning, but now they are used to fell the groves that embody him. There is something more complex, though, about the shift from dark to light. Like the dappling of sunlight and shade on the forest floor, or the layered interplay between the living and the dead, the process is less a clean slate than an entanglement.

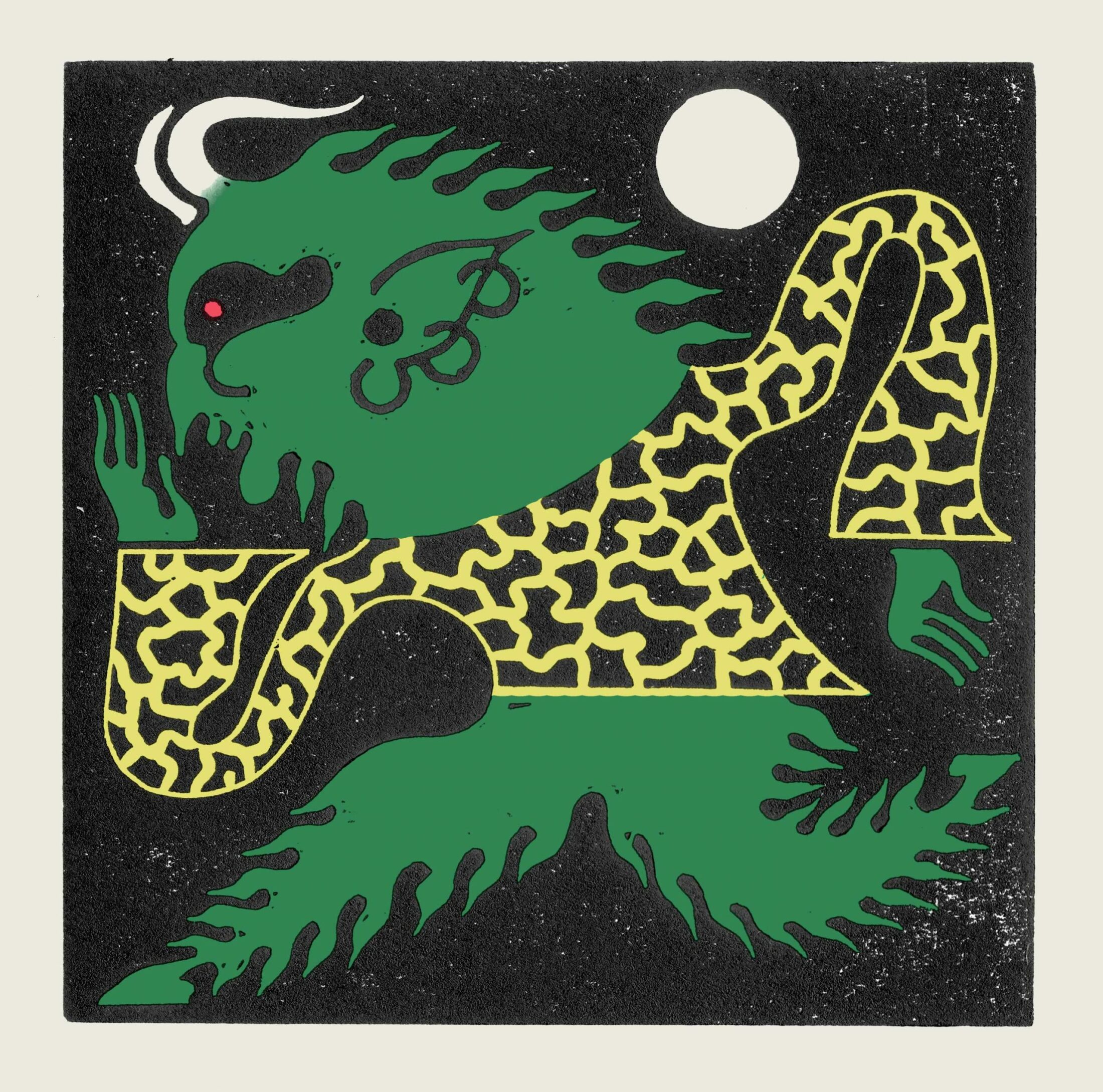

Post-Christian depictions of Perun show him as a figure on horseback killing a serpent with a lance, an image almost identical to that of St. George and the dragon. As with the Norse god Thor, the Greek Zeus, the Roman Jupiter, and other deities of the sky, the Christian myth is overlaid on the preexisting pagan one; the sky god does not so much replace Perun as merge with or grow into him, as the limbs of different trees meet and graft together. Veles of the underworld—the earth deity recast in the form of a Satanic snake—is trampled underfoot and pierced through with metal. Unlike in the old Slavic myth, he does not creep back again as part of an ancient balancing. The cycle has been interrupted. Light triumphs over darkness, the sky over the earth.

But outside the figure of Christ-Perun, the old gods endure much longer in this part of Europe than they do elsewhere. On the northeasternmost fringe of Europe, forest-dwelling tribes of Balts, Finns, and West Slavs cling to their ways so obstinately that in 1195 Pope Celestine III launches the first of the Northern Crusades to force them to convert. This series of genocidal invasions is carried out by the Teutonic Order, which slaughters its way northward through the Livonians, Latgallians, Selonians, Estonians, Curonians, Old Prussians, and other tribes who attempt to resist the coming of the light. The last Lithuanians and Poles are converted by the order of Władysław II Jagiełło—the king embodied, Perun-like, in the form of a century oak—two centuries later.

One derivation of the woodland gods that survives the clearances is the figure of the Leszy, which translates as something like “Woody.” This guardian spirit of the trees—humanoid, hairy, sometimes horned, often surrounded by wolves and bears—is morally ambiguous, neither evil nor good; he can either lead travelers astray to become hopelessly lost or guide them safely home. The enduring popularity of this small god of place, along with a pantheon of other woodland folk spirits, causes the Church to bemoan the semi-heathen ways still practiced in modern times.

Some of them, in this staunchly Catholic country, are still practiced today. As evidenced by the seven china plates beneath that spruce, pilgrims are still coming here—to this quiet Place of Power—to leave offerings to trees.

This guardian spirit of the trees—humanoid, hairy, sometimes horned, often surrounded by wolves and bears—is morally ambiguous.

Around mid-morning we stop to eat some lunch near a moss-covered hornbeam. On the ground lies the ghost shape of a lime that rotted and disappeared forty or fifty years ago, in the acidic shadow of which wild garlic still doesn’t grow. My guide identifies the acrid, pungent scat of wolves. Three days old, she says.

Wolf shit isn’t the only clue to the ancient beasts that lurk here. Deeper into the trees, the undergrowth parts to reveal a hunk of purple meat the size of a concrete breeze block, boiling with maggots. Further on lies a heap of bones that are grotesquely oversized: vertebrae the size of fists, a leg bone that resembles a cartoon Stone Age war club. Propped against an oak stump is the broad chest plate, clumped with curly brownish fur.

With mental paleontology I can reconstruct the rest: it is Białowieża’s iconic beast and the national animal of both Poland and Belarus, the żubr, the wisent or European bison.

Bison—forest-dwelling cousins of American buffalo, which they closely resemble—once roamed the North European Plain, but few would now recognize them as a European animal. They are more easily pictured thundering over Midwestern prairies, pursued by Apaches on piebald horses or gunned down by white men from trains. But bison are survivors of another, more ancient frontier. Descended from aurochs, the ancestors of modern domestic cattle, they were driven from Europe’s own Wild West as the forest was pushed back.

With the old gods of the trees, they retreated into the shadow.

Bison and Białowieża are mutually dependent. Without the protection of the forest, the bison would not have survived, yet without the bison—and their status as a hunting animal prized by Polish-Lithuanian kings and later Russian tsars—it is probable that the forest would have fallen long ago. Hunted to the point of extinction during the First World War, when occupying German troops butchered them for their meat, they vanished until 1929, when today’s population was reintroduced from captive breeding stock. Apart from this brief interregnum, their presence in Białowieża stretches back for thousands of years. They are truly archetypal. The same massive, thrusting chests, patriarchal beards, and upward-curving horns appear—gracefully daubed in ochre and manganese—in Upper Paleolithic cave art, painted twenty thousand years ago.

The glaciers had not melted, then. The forest had not grown.

Bison are deeply of this continent, older even than the trees. Matted root balls hummocked with moss, their horns a sharp and deadly wood, they resemble shaggy fragments of the forest come to life.

These Leszys are still out there somewhere, in that labyrinth of trees. During my time in Białowieża, I do not lay eyes on them—it is the wrong time of year and they are deep within the woods—but perhaps, peering through the leaves, they see me.

We push through dense sapling growth and go carefully through spiked obstacle courses. Where fallen trunks have blocked the path, she goes under and I go over. Perun’s oak and hornbeam groves darken into alder swamps fringed with the willow of Veles, where new trees sprout from islets formed from ancient stumps. The textures and consistencies of rotting wood are wildly varied, from chitinous walls of gleaming black, webbed with residues of slime, to spongy flakes and dry crumbs indistinguishable from soil. The surface of the water is marbled with sludgy bands that look like slicks of chemicals, but are, says my guide, the drifted pollen of lime trees. In all but the coldness of the air, this rich, creative rot might be a tropical jungle.

Passing back into lighter woods, we come upon a monument to another kind of death: two wooden crosses that mark the site of a massacre. In the Second World War, German soldiers brought two hundred local people here, gunned them down, and shoveled their bodies into a mass grave. Such collective punishment for the actions of partisans, who used the forest as a hiding place, was a common terror strategy; there are reckoned to be over a thousand such corpses in Białowieża.

A human body, unembalmed, rots much faster than a tree. Depending on the temperature and the environment in which it is laid, most of it will disappear within a decade. It passes through five main stages—fresh, bloat, active decay, advanced decay, and skeletonized—during which it is assailed first by its own bacteria, which start digesting its soft tissues within a couple of days of death, and then by staggered waves of other organisms. Blowflies lay their eggs, maggots hatch and start to feed, rapidly consuming most of the body’s mass—being consumed themselves by predatory beetles, wasps, and ants—opening holes in the flesh that provide ingress to other insects, funguses, and protozoa and allowing fluids to seep out. The body stiffens and relaxes, bloats and evacuates, turns from green to purple to black, putrefies and liquifies until only the dense material of cartilage and bone is left. The microbes, maggots, beetles, and funguses have done their work, disturbance agents recycling nutrients into new life, to be distributed through cell-thick networks of mycelium.

These corpses have become part of the forest, encoded in its pattern.

The nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium, and potassium that are released into the earth alter the chemistry of the surrounding soil for years. I think of the death shadow of that lime, where wild garlic doesn’t grow.

The granite memorial at this site, with its graven Polish words, will endure for a couple of centuries, perhaps. But the crosses are simple sticks with the mossy bark still on them. It seems right that they will also rot, in a short space of time, becoming one—becoming many—with this living dead wood.

The sun is up above the trees, sending spears of light to lance the dimness of the forest floor. Nearing the entrance gate, my guide almost steps on a gray snake that flows like water beneath her boot and slides away into the earth.

A farewell from Veles, going back to the underworld.

As we step across the threshold of the rustic wooden gate, my guide removes her green hat to reveal neat blonde hair. Together we step into the light and back into The Clearing.

Halfway across the pale meadow, I pause for a last look back. A lone oak stands near the gate, outside the boundary of the woods, not straight-trunked and tall but wide-girthed, crouched and squat. I did not notice it before. Sunlight falls on its uppermost leaves, but the ground beneath is dark.

It seems to be waiting for something.