Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

Fraser Jones is a filmmaker from Atlanta, Georgia. His debut feature film, Your Ride Is Here, is currently touring the international film festival circuit. Fraser’s current project, We Can’t Breathe, is a documentary film that takes place in Uniontown, Alabama, a primarily African-American town that has fallen victim to continuous acts of environmental injustice and racism.

Extracted iron ore can be forged into a weapon. A gun can be melted into a shovel that is used to plant a tree. Through a radical reimagining of what a gun can be, this essay considers the power of intention, where the means determine the ends.

My son is a human being—was a human being. My son was such a good person. My son was our first baby in the family,” says Monteria Robinson, the mother of Jamarion Robinson.

“My son was loved.”

In 2016, the year Jamarion Robinson was shot and killed, guns took the lives of 37,200 people in the United States. Americans own an estimated 265 million guns, more guns per capita than civilians of any other country.

“I have to be the voice for my son.”

The life of a gun begins in the ground. Iron ores—rocks and minerals containing metallic iron, the fourth most common element in the earth’s crust—vary in color from purple to yellow to gray to rust red. The Mesabi Iron Range of northeast Minnesota has a narrow belt of sedimentary rock rich with such ores. The Hull-Rust-Mahoning Mine, one of the world’s largest open-pit iron mines, has been operating here since 1893.

Open-pit mining is a surface mining technique, used to extract rock and minerals from the earth. To create an open-pit mine, vegetation and soil—“overburden”—are stripped away by machinery. Drilling and blasting expose the ore. Excess rock—“waste”—is hauled by trucks to dump sites. As the mine expands, tiered walls step downward into an increasingly narrow, exposed chasm. The Hull-Rust-Mahoning Mine is eight miles long, two miles wide, and six hundred feet deep.

Once extracted, iron ore is crushed into a fine powder and magnets remove impurities. What remains is fed into a blast furnace and mixed with coke (a coal-based fuel with a high carbon content), lime, and oxygen, purifying the iron further.

The molten metal that runs out of the tap hole and into the ladle at the end of this process is iron transformed into steel.

A gun is assembled by a person whose two hands fit together its component parts: various steel pieces which have been shaped by a forging press and then reheated to stabilize flow patterns and eliminate internal stress. Frames, sideplates, sights, and triggers are milled in machining centers. Cylinders, screws, shafts, and barrels are manufactured on lathes. In certain guns the barrel is rifled: fitted with a series of grooves in a precise spiral. Computer-controlled technologies can machine steel within one- or two-thousandths of an inch of specifications. But a person must set the timing of the trigger.

On his last Christmas Eve, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a sermon at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. “We will never have peace in the world,” he said, “until men everywhere recognize that ends are not cut off from means, because the means represent the ideal in the making, and the end in process, and ultimately you can’t reach good ends through evil means, because the means represent the seed, and the end represents the tree.”

The knowledge contained in a seed is extraordinary, prophetic. Lay it in the ground, and with the right conditions, it will fulfill a destiny, branching and leafing, interpreting the combined scripture of its external environment and DNA.

Neither iron ore within the ground nor seeds that are to become trees have moral intent. But the sort of seed that is planted in the imagination is able to wield iron to specific ends. Pedro Reyes, a sculptor who works extensively with metal, knows this well. It is our intention in harvesting materials and putting them to use, he says, that gives moral weight to our tools and technologies.

The ability to transform iron into steel—extracting ore, and then melting, forging, milling, and machining it into all sorts of shapes—has resulted in skyscrapers, jet engines, pipelines, weapons. From our early ancestors’ use of fire, to wood, stone, and eventually metal, technological innovations are widely taken as a positive example of human evolution.

But Reyes believes that modern technology is too often the ally of a primitive mindset. “They’re extremely primitive motivations. And that has to do with capitalism and the military sector. There is a spiritual problem but also a practical problem with so-called innovation, because innovation is often driven by two motors: one is the desire to increase profit and the other is military.” The gun industry contributes an estimated $50 billion annually to America’s economy.

An idea can pull away mountainsides, can turn ore into gold. Here lies the embodiment, the power, of an intention.

Steel, a vastly superior material to raw iron, is able to contain and direct the explosion that follows the pull of a trigger which sends a bullet down a barrel.

Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee.

“Sculptors basically transform matter. You change the shape of things,” says Pedro Reyes, sitting in his bustling studio in Mexico City. His own work has been a study of both the consequences and the imaginative potential of transforming and using materials. “I believe that the thing that is most needed is imagination.”

In 2008, Reyes launched his project Palas por Pistolas in Culiacán, Mexico, a city with a high incidence of gun violence. Inspired by the work of Joseph Beuys—a German artist who planted seven thousand oak trees in response to industrialization—and Antanas Mockus—the mayor of Bogota, Columbia, who melted down weapons into spoons to feed babies—Palas por Pistolas enabled citizens to hand in weapons in exchange for coupons which could be traded for domestic appliances.

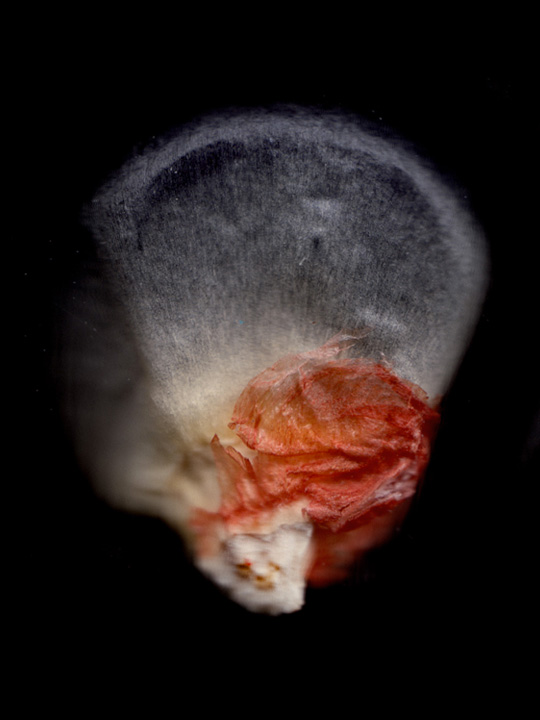

Each of the 1,527 weapons collected was melted down and recast into a shovel. Those 1,527 shovels are now being used to plant 1,527 trees.

“Palas por Pistolas was a process that was melting and recasting that metal, which was a physical transformation. The idea of alchemy is that physical transformation goes hand in hand with a psychological transformation—and a change of polarity, so to speak—of a technology that was made to kill to a tool to give life.”

To transform a gun into a shovel, it must be returned to the fire. Coke—the high–carbon content fuel—heats a furnace to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. Cast iron is broken into pieces and put into the furnace where it turns to a liquid metal. This spitting, molten mixture is now ready to receive a firearm. When a gun is added, those precisely forged and machined components begin to disassemble. Particles break from their bonds. Atoms are free to move. The metal enters into a fluid state, blending with the cast iron, its purpose disintegrating along with its form, returning to a material that is again ready to be shaped.

Installation of Palas por Pistolas, 2009.

Photo by Stephane Rambaud, courtesy of Biennale de Lyon.

As the King Center in Atlanta is preparing an event commemorating Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and legacy on the fiftieth anniversary of his assassination—April 4th, 2018—Kyle Lemle, brontë velez, and a box of dismantled guns are on their way to Georgia from Oakland, California.

Kyle, a forester, and brontë, an artist, share the belief that the ecological crisis facing our planet is rooted in a spiritual crisis. The destruction of lands and waters and the physical violence happening in our communities emerge from the same set of values: selfishness, greed, apathy.

It has been fifty years since the death of Dr. King and nearly five years since brontë’s friend X’avier Arnold was shot and killed in her home city of Atlanta. brontë and X’avier became friends in high school, bonding over art and music. Their families attended church together. Nichole Villafane, X’avier’s mother, remembers that as a child, X’avier used to stand at the top of the stairs and declare proudly, “I’m Superman. I’m never going anywhere.” He and Nichole would laugh and joke about Kryptonite.

“In 2013, we all got the devastating news—more devastating for me than anyone else—that my son had been shot,” says Nichole. “It ended up being the final day for my son.” A fourteen-year-old boy attempting to mug X’avier shot him when he resisted. X’avier’s was the eighty-third of eighty-four gun deaths in Atlanta that year. That number has continued to rise in the years since, in a city that is far from alone in its inability to keep guns out of the hands of youth, far from alone in a dark legacy of gun deaths.

Neither Kyle nor brontë ever held a firearm before collecting the guns; neither of them ever wanted to hold one. They are bringing the guns to Atlanta so that they may be destroyed by fire.

But first, there is preparation to do.

brontë hands Dr. Bernice King a gun to be delivered to the furnace on the 50th anniversary of her father’s assassination.

Photo by Eddie Velez

Less than a week before the event at the King Center, brontë and a group of people who identify as part of the African diaspora gather together in a forest near Roswell, Georgia, a site they’ve learned of through the Equal Justice Initiative’s Community Remembrance Project, which collects soil from lynching sites and archives the names of people killed in racial terror violence. This forest is the place where a black man named Mack Brown was lynched in 1936. “There’s a haunted relationship to forests in the South,” says brontë. Here in the woods, near the river, the group gathers water and sings. They invoke names and pray for healing: for themselves, for each other, for their ancestors, for the trees. They collect soil that will be used in tree plantings at sites of trauma across Atlanta over the course of the following week.

On April 4th, the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, brontë and Kyle are at the King Center, standing outside the Coretta Scott King Peace Garden. Dr. Bernice King—Martin Luther King Jr.’s youngest daughter—has just shared the experience of losing her father. She is surrounded by families who have lost loved ones to gun violence and several hundred community members. Everyone stands in reverent silence as she is handed a gun, the first weapon she has ever held. The community witnesses her walk the weapon to the cupola furnace, a head-high cylinder, spitting orange sparks atop three curved metal legs. With the assistance of metal artist Jim Brenner, she places the gun into the fire. Several minutes later, the melted metal pours through a spout and then into a mold, shaped into the handle and blade of a shovel. The shovel is used to plant a tree at the Center. Soil from the forest in Roswell is laid into the ground around the roots.

Two days later, at the “Reimagine Violence” ceremony, an empty lot a few blocks from the King Center is the setting of a community ritual. Jim again sets up his furnace. Before attendees arrive, brontë builds an altar on the asphalt: candles, slices of trunks from felled trees, the wooden stocks of rifles, a trowel, and tobacco, rice, and cotton—plants tied to a history of violence and slavery. “At the core of the faith traditions is something very profound that we don’t have to reinvent,” she says. “We can come back to the truth of [these traditions]. Not the ways they got entangled with capitalism or the ways they got entangled with power, but to say what’s really here … People want to sing together, they want to gather, they want to heal, they want to meet. They want to feel spirit.”

With the community gathered, Kyle invites everyone to write a prayer for transformation and drop it into the furnace. Sparks rain onto the pavement.

Mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters arrive to speak of their loved ones lost to gun violence. Each delivers a gun to the flames. Jamarion Robinson’s aunt and grandmother attend the ceremony in place of his mother, Monteria, who is unable to come. Drums, poetry, and song are interspersed with storytelling.

Nichole, X’avier’s mother, also attends this ceremony. She is unsure what to expect, uneasy at the idea of being around guns, but she wants to speak about X’avier; she wants to see the weapons destroyed. One by one, families are handed firearms and approach the furnace, until it is her turn. She watches the melted gun being poured into the shovel mold.

“I began to visualize my son in another light,” she says. “I actually felt closer to him, and I felt like we were giving his spirit and his energy another chance to evolve in another way.”

Alchemy is the transformation of base metals into gold; a power or process that changes or transforms something in a mysterious way; an inexplicable or mysterious transmuting. Extracted iron ore forged into a weapon. A gun melted into a shovel.

“X’avier taught me this before he passed away—amazing what the spirit does to get you prepared—he told me that he was made up of energy and that, if anything was to ever happen to him, he would never die. His flesh would be gone, but his energy would last forever,” says Nichole. “The experience of watching them melt this metal that has wreaked havoc in my family’s life—to see that iron melted down and turned into something beautiful that is a work of art—it was surreal to me.”

Serotiny: The Story of Lead to Life, directed by Fraser Jones

Several days later, using the shovel that was cast from a melted gun and given to her family, Monteria Robinson plants a tree for her son.

Her family gathers in her yard, each wearing a shirt featuring a picture of Jamarion. The handle of the shovel is inscribed with the words: As we decompose violence, may the earth again be free. Together, they dig into the soil and plant a crape myrtle for Jamarion.

They stand together, eyes closed, and pray over the myrtle tree.

“Each year it turns different colors,” says Monteria, five months after the planting. “This year it turned pink. I always look at it. To me it’s like a symbol of him.”

Nichole Villafane, too, plants a tree. Together with her youngest son, X’avier’s grandparents, his girlfriend, and brontë, she goes to the site of his murder and plants a redbud tree. She places some of X’avier’s ashes into the soil. They all eat some of the flowers. It feels to Nichole as if she is channeling her son back through something tangible, something solid and beautiful.

Later that afternoon, they plant a ginkgo tree at her home. “When the tree was delivered to the house, I felt like X’avier was coming back to me. I know that’s weird, because it’s not flesh; the tree can’t speak to me or anything … I just felt my son is here. The ground would be blessed with his spirit and his energy.”

Kyle and a group of planters hold shovels made from guns, during a Permaculture Action Day in Atlanta.

Photo courtesy of brontë velez & Kyle Lemle

Bryson Velez waters a cherry tree planted at the King Center with a shovel made from a melted gun.

Photo courtesy of brontë velez & Kyle Lemle

“There are technologies of war, technologies of surveillance, technologies that poison the earth, technologies that are made to help the rich get richer,” says Kyle. “And then there are positive and morally sound technologies … those helpful tools and helpful systems that catalyze healing and connecting and abundance … I think we have that sacred responsibility to recognize our own power and recognize the sacredness and profound responsibility of imagination … going back to the root and creating technologies that help people imagine into being a more peaceful way of life on planet Earth.”

The shape of a gun transforms into a shovel and trees are planted: a ginkgo and a redbud are placed into the earth.

A crape myrtle blooms pink this year. Monteria and her family stand in a circle around the tree—hand in hand, feet on the ground—its roots reaching into the soil, its trunk expanding, its crown spreading up and out, into the sky.