Bear Guerra is a photographer whose work explores the human impact of globalization, development, and social and environmental justice issues, often in communities typically underrepresented in the media. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Le Monde, BBC, and NPR, and has been exhibited widely. He was a finalist for a National Magazine Award in Photojournalism. Bear and his wife, Ruxandra Guidi, work together under the name Fonografia Collective to produce local and international print, radio, and multimedia stories about human rights and social justice. Bear is also a board member and producer with the award-winning nonprofit journalism collaborative, Homelands Productions, and is the visuals editor at High Country News.

Following the Los Angeles River from source to sea, this photo essay is a meditation on the human desire to tame the natural world, highlighting both the suppression and resiliency of a river that flows through a sprawling city.

For most of the year, the river’s flow consists primarily of treated wastewater and runoff from neighborhoods across the city.

View from Fourth Street Bridge

Samuel fishes under a highway bridge near “Frogtown”—a neighborhood whose nickname comes from the vast numbers of young Pacific chorus frogs and western toads that used to emerge from the river every spring and blanket the river’s banks. But loss of the riparian habitat and alteration of the natural water flow have devastated the once famous frogs of Frogtown. Today, it is a challenge to find them at all.

Frogtown

José Carlos, a homeless immigrant from Guatemala who’s lived next to the river for more than ten years, walks down the bank to bathe in its water. Though the majority of the river is completely encased in concrete, in this eleven-mile stretch known as the Glendale Narrows, the underground water table rises close to the surface, allowing for a natural soft bottom and constant flow of water. Though many of the plant and animal species that now flourish in this area are non-native, one can get a glimpse of what this habitat might have been like before channelization.

Near the Bowtie, Glendale Narrows

A man looks at the raging river as it passes through an industrial section near downtown during a winter storm. The river’s regular seasonal flooding became problematic as the city grew in the early 1900s, and by the 1930s, the decision was made to transform the waterway into a massive flood control system.

Olympic Boulevard

(left) Davison Locksley, an actor and longtime resident of Los Angeles, rides his bike along the river every day for exercise and a sense of connection to nature.

(right) “Catman” has lived in a tent along the river for nearly a decade. There is a large population of homeless people who have sought out the relative safety and peace near the river, away from the dangers of the street. With recent plans for a “revitalization” of the river, it’s only a matter of time before these men and women are forced to find somewhere else to call home.

Glendale Narrows

A tree near the mouth of the river in Long Beach bears the scars of countless people who have sat in the shade of its boughs.

Long Beach

(left) With one of the largest populations of homeless people in the country, homeless encampments—whether occupied or abandoned—are a frequent sight along some stretches of the river.

(right) Leaves and trash hang from a tangle of branches in the middle of the soft-bottom section of the river after a winter storm. In a city now living in a perpetual drought, it seems like a wasted opportunity that the vast majority of the water during storms is just flushed out to sea.

Glendale Narrows

(left) A piece of fabric hangs from a tree in the Sepulveda Basin Recreation Area after high waters have subsided following a winter storm. Sepulveda Basin is one of three natural-bottom stretches of the river that exist today, all of which support the majority of the river’s remaining wildlife populations.

(right) The tattered remains of a shirt almost blends in with the embankment along an industrial section of the river south of downtown L.A.

Left: Sepulveda Basin

Right: Southgate

A shirt that has become wedged under a rock flows with the current of the river.

Glendale Narrows

Sepulveda Basin

The sun reflects on a broken mirror discarded near the river. One of the most formidable challenges the city will face in the coming years as plans to “revitalize” the river move forward will be encouraging the wider public to value the river.

Glendale Narrows

(left) The sun shines through an overpass near where the Glendale Narrows stretch of soft-bottom river begins.

(right) “Mykey” looks at one of his pieces of spray art inside a tunnel that feeds into the river. The river draws a diverse cross section of people who value the sense of escape they feel along its banks.

Glendale Narrows

(left) View of the confluence with the Arroyo Seco River, from inside the channel. Though one would never know it today, the lushness and beauty of this spot where the two rivers converge influenced Spanish explorers in the late 1700s to found the city of Los Angeles nearby, rather than closer to the ocean.

(right) Abandoned shopping carts are an all too ubiquitous sight in the Los Angeles River. But, every spring, river supporters and activists host a massive cleanup effort to remove the huge amount of trash that ends up in the river throughout the year.

Left: Confluence of the Arroyo Seco and L.A. Rivers

Right: Glendale Narrows

Though most of the diverse native species no longer roam the shores of the river, one can still find small populations of several of them, as well as common urban species, like this flock of pigeons.

Confluence of the Arroyo Seco and L.A. Rivers

Pigeons fly above a stretch of the river only a few dozen yards away from one of the most congested freeways in the country—the I-5.

Glendale Narrows

(left, right) Though its bird species diversity pales in comparison to what it would have been before the city’s rapid development and the channelization of the riparian habitat here in the mid-1900s, the L.A. River still supports a sizable population of resident and migratory bird species.

Glendale Narrows

A coyote passes through the Bow Tie Yard, a former rail yard adjacent to the river in northeast Los Angeles, near downtown. Whereas most of the native mammals that would have wandered along the banks of the river are now gone due to habitat loss, coyotes have managed to adapt to life in places where some degree of wildness can still be found.

Glendale Narrows

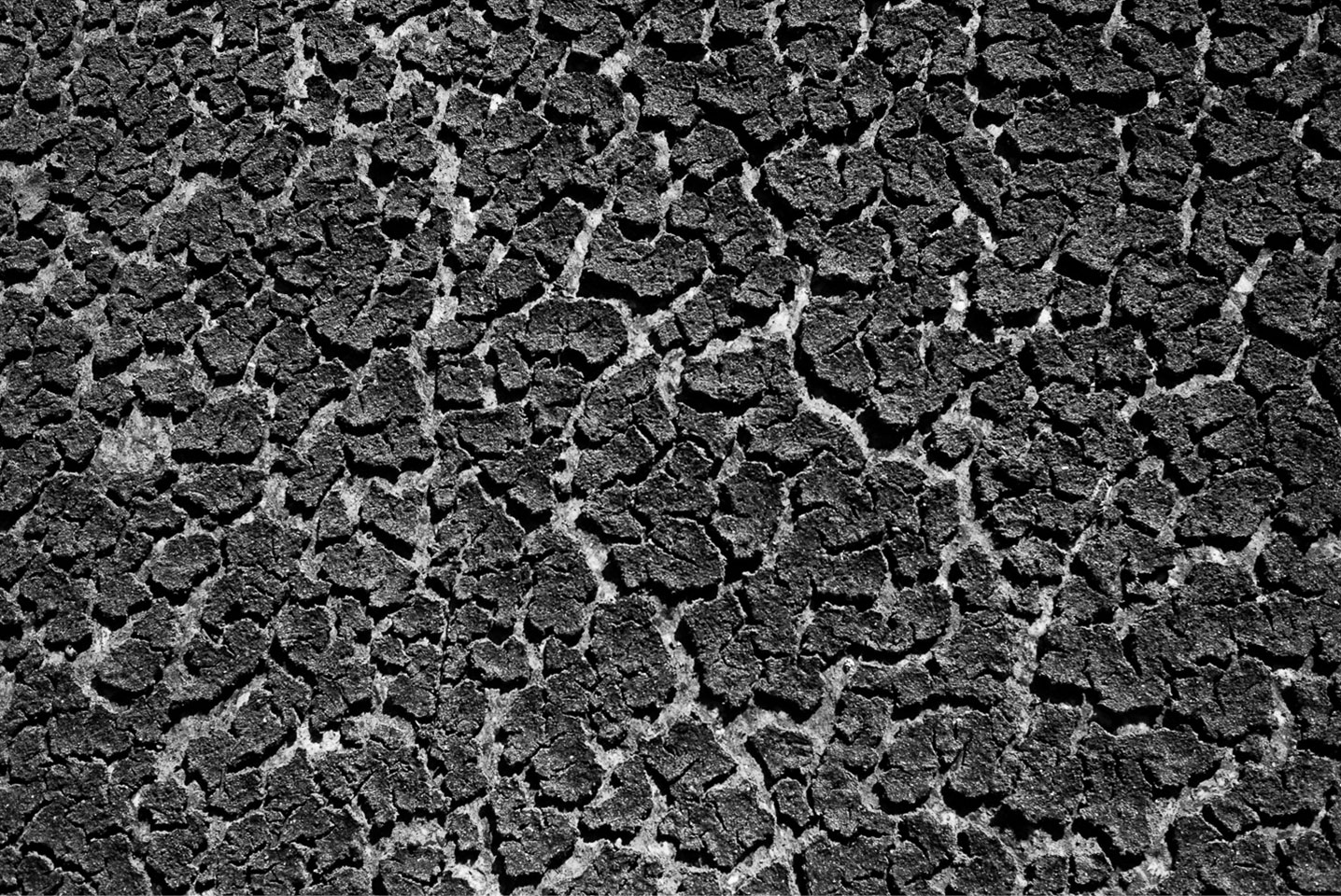

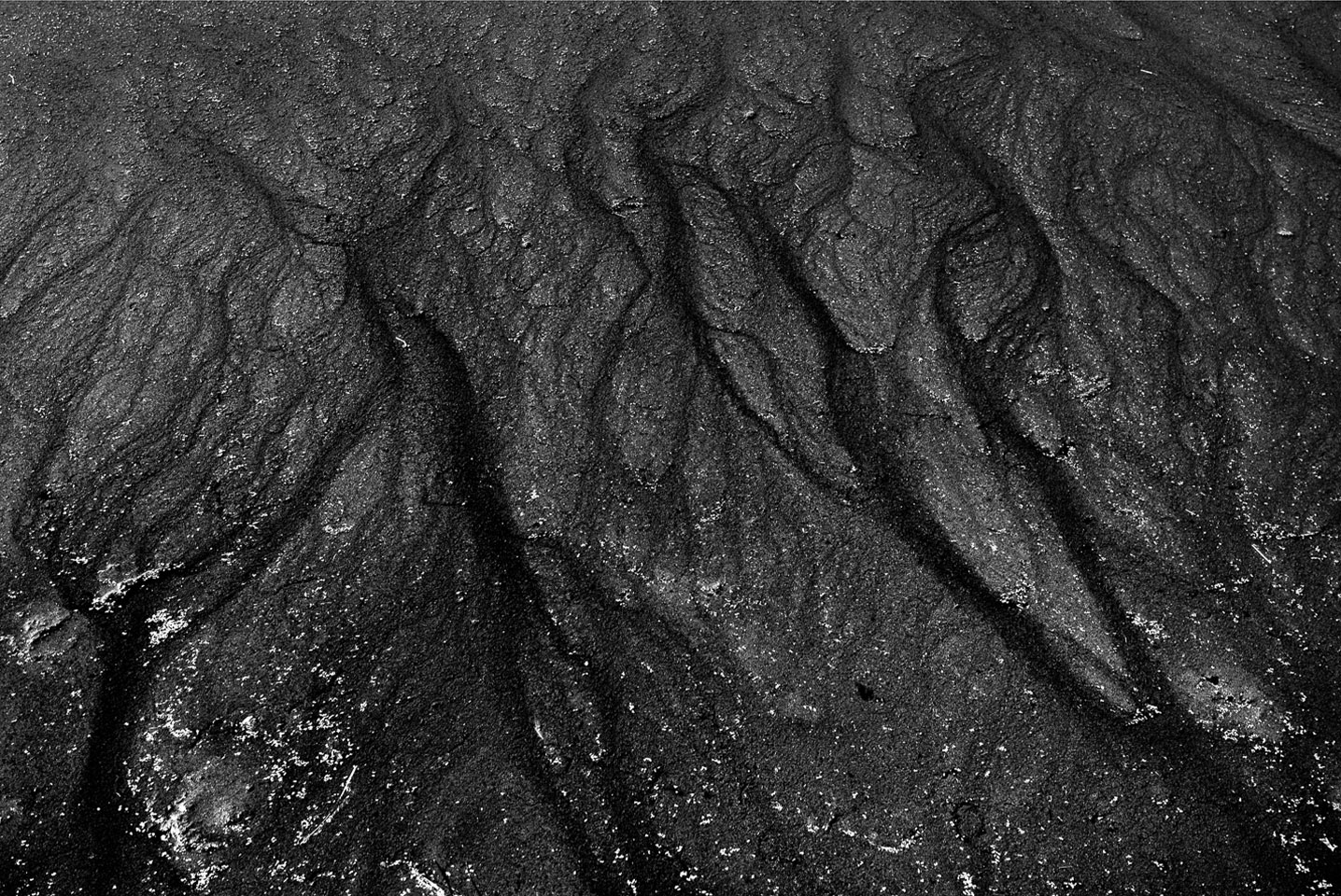

Tracks left by raccoons and birds (left) and people (right) point to some of the denizens of the river.

Sepulveda Basin, Glendale Narrows

Abstract patterns photographed in the river.

Glendale Narrows

View from Fourth Street Bridge

(left) Despite this massive human project to contain the river and control this natural environment, in some areas there are signs that the concrete won’t last forever.

(right) Though the Sepulveda Basin Recreation Area is also part of the engineered flood control channel, the river feels as if it is flowing in an almost natural state. Here one can glimpse a possible future for the river in which nature could be allowed to return, if concrete were to be removed.

Left: Glendale Narrows

Right: Sepulveda Basin

There have been talks of revitalization and restoration of the L.A. River for many years, and now a $1 billion plan is in the works. Though improvements to the river are long overdue, many fear that they will also bring a spate of development.

Beginning of Glendale Narrows

The river is reflected under a freeway overpass in Frogtown, one of the river-adjacent neighborhoods currently seeing a rapid rise in property values, while just beyond willow trees grow on an island in this soft-bottom stretch.

Glendale Narrows

Glendale Narrows

Despite the profound impact on the native habitat of the Los Angeles River over the last century, nature still manages to flourish in a few stretches along its path, offering a sense of the wild in the middle of one of the most congested urban environments in the world.

Glendale Narrows

As a resident of Los Angeles, California—a megalopolis with the dubious distinction of having one of the lowest percentages of public green space for any city of its size or stature—I find that what little nature remains is indispensable. One of the places I return to again and again to escape the chaos of the city is the Los Angeles River: Southern California’s most poignant symbol of human efforts to alter the natural environment in the pursuit of development.

Because the river is prone to intense flash flooding during the wet winter season, the 51-mile-long waterway became increasingly problematic as the city expanded in the early twentieth century. In the late 1930s, the L.A. River was channelized in what was proclaimed a triumph of man over nature, transforming it into the giant concrete scar that winds its way from Canoga Park to the Pacific Ocean.

Surprisingly few Angelenos are even aware that the massive man-made drainage ditch they see from the freeway was once a verdant habitat for a diversity of birds, mammals, and fish; or that today there are still several soft-bottom stretches where natural springs prevented the concrete from taking hold, offering a rare chance for nature to thrive amidst the sprawl. One has to know where to look, but a sense of what once was here—before all the cars and people—can still, to some extent, be found.

Thanks to the work of a dedicated group of activists, more locals are now advocating for the river, and the city has recently responded with a $1 billion plan to “revitalize” it to encourage more public use—an effort that has been long overdue. But with plans for revitalization, many fear that nearby residents—including a large homeless community and working-class neighborhoods along the river’s banks—will soon be displaced, as developers have set their sights on river-adjacent properties. More housing and commercial developments, in turn, will threaten the fragile ecosystems that the effort purports to bring back.

I can’t help but wonder to what extent the river could return to what it once was, given that this landscape has been so severely altered over the last century. Much of the plant and animal ecology along the river is either gone altogether or—where it does still exist—no longer native, having been largely replaced by invasive species. During most of the year, the water that flows through the channel is primarily treated wastewater; and during winter, when it does rain, the freshwater just flows right out to sea, wasting an opportunity to save it for the dry months.

Yet, for many of us, the L.A. River is also emblematic of what could be.

In this photo essay, I am pondering nature and wildness in a place where the powerful have relentlessly trampled over them time and time again. It’s an exploration of the inherent need for the wild in our lives, despite our unending and often unsuccessful efforts to tame it.

This is also a meditation on the resiliency of the natural world despite what’s been lost; and of a river that might be possible, if we can learn from the mistakes of the not-too-distant past.

Some photographs in this essay will also appear as part of the project South of Fletcher: Stories from the Bowtie.