Lorraine Eiler, near Ajo, Arizona.

Photo by Bear Guerra

Rights of Nature at the Border

Lorraine Eiler is a Hia-Ced O’odham woman and a San Lucy District Alternate of the Tohono O’odham Legislative Council. She serves as a member of the Healing the Border Project, which works to protect sacred sites along the US-Mexico border primarily through community organizing, legal strategy, and public education. She contributed to the 2021 resolution that affirmed the legal personhood of the Saguaro cactus, called Ha:sañ in the O’odham language. Lorraine leads educational tours in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, ancestral O’odham lands. She lives in Ajo, Arizona.

Bear Guerra is a photographer whose work explores the human impact of globalization, development, and social and environmental justice issues, often in communities typically underrepresented in the media. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Le Monde, BBC, and NPR, and has been exhibited widely. He was a finalist for a National Magazine Award in Photojournalism. Bear and his wife, Ruxandra Guidi, work together under the name Fonografia Collective to produce local and international print, radio, and multimedia stories about human rights and social justice. Bear is also a board member and producer with the award-winning nonprofit journalism collaborative, Homelands Productions, and is the visuals editor at High Country News.

As the border wall and climate change disrupt the ecological balance at Quitobaquito Springs, an oasis in the Sonoran Desert that serves as one of the most sacred sites for the Hia-Ced O’odham people, Lorraine Eiler speaks on behalf of the more-than-human beings who inhabit this place and deserve to live with integrity.

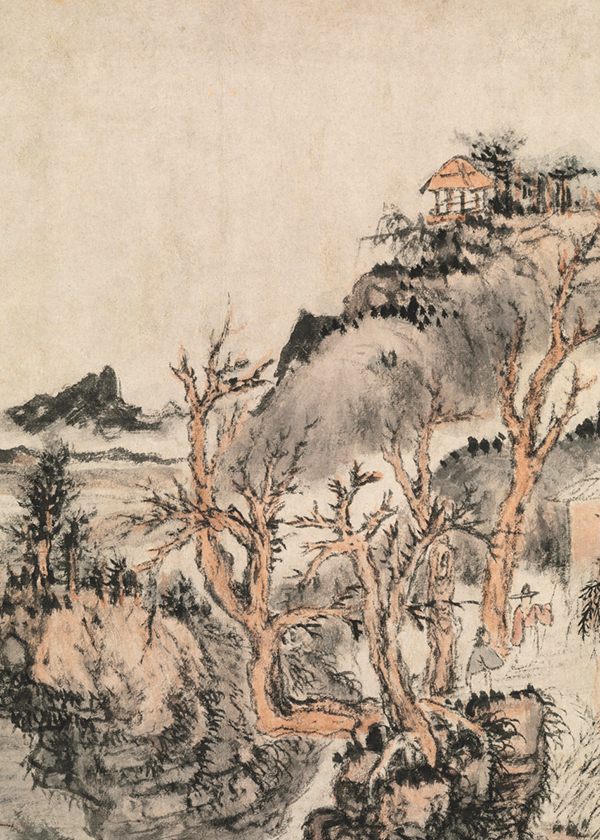

If you were ever out in the Sonoran Desert at nighttime and you saw the shadows, you’d swear there were people standing out there with you. The towering Saguaros, or Ha:san as we call them in our language, their arms figured in countless postures, stand like humans. For the O’odham, who have lived in this desert since time immemorial, the Saguaros have a right to flourish here, just as we do.

As a Hia-Ced O’odham woman, I have long known this desert to be a place of miracles, and these miracles have arisen again and again to sustain my people for many generations. My ancestors survived by working the land, by harvesting and drying food—wild spinach, wild onions, Saguaro fruit, cholla cactus flower buds—by camping out and hunting, and by knowing where to collect water. Always, the land provided these things.

Quitobaquito Springs, an oasis in the desert that serves as one of the most sacred sites for my people, has provided a continuous source of water for the Hia-Ced O’odham, who settled here many generations ago. My great-grandparents resided in the area prior to 1910. Other kin lived there until the mid-1900s, when they were forced from the area by the National Park Service, which cleared the land of any Indigenous presence to establish a sense of an empty wilderness—a common practice in national parks across the country. Now enveloped by the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Quitobaquito is just two hundred yards from the US-Mexico border. The springs, already under duress from drought, have been further threatened by border wall construction.

In 2020, as the construction crews moved closer, we were at Quitobaquito performing one of our ceremonies. For months, contractors had been cutting into the land with their machines all across the southern border of the national park, knocking down whatever was in their way, including the Saguaros. They were pumping precious water out of the aquifer to mix their cement, and the water level of the pond at Quitobaquito—one of the only consistent above-ground sources of water in the 86,000 square miles that make up the Sonoran Desert—was dropping and dropping.

We were there that day in protest, in community, and in ceremony. Some people were singing when several Sonoyta mud turtles came to the edge of the pond. Somehow they seemed to be moving with the flow of the music. It was magical to see, and it helped us feel that we weren’t alone in this, that we weren’t just fighting for ourselves. We were also fighting for all the creatures around us, because the border wall was not just separating people from each other, it was separating entire ecological communities.

There is archaeological evidence that people, plants, and animals have continuously inhabited Quitobaquito Springs for thousands of years. My ancestors were dependent upon this wide, diverse landscape and its gifts. Many people today cannot see those gifts when they look at the desert, but I was taught that the different forms of life in the desert are intricate parts of our own being: the animals, the plants, the water. We had to learn how to live in these areas; we needed a wealth of knowledge in order to survive. As late as the early 1900s, when my family lived here, it was a thriving place. There were medicinal plants and more birds than you can imagine. There were orchards of pomegranates, figs, and grapes, and fields of different crops. There was abundant wildlife. Today, even though I have been taught to harvest, I don’t think I could live off the land in the same way my great-grandparents did. I often consider how amazing it was that they endured for so long in this dusty land that they trusted would provide everything they needed.

But with the arrival of settlers—Spanish missionaries, miners, and soldiers—access to this vast landscape became smaller and smaller for my people, until at last the encroachment became unbearable and my family was pushed out. After that, anthropologists came to places like Quitobaquito—places they knew were sacred sites for the O’odham people—and, seeing no one left there, they considered my people extinct.

But we are not extinct. We are here, and we are still bringing our knowledge to bear in our ongoing, evolving relationship with this landscape.

When they were in the midst of building the border wall, the United States government found ways around dozens of environmental laws that had taken years to put into place. They went through wilderness areas; they went through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Whatever was in the way, they bulldozed, dynamited, and destroyed; but it was the destruction of Saguaros that brought things to a head.

Saguaros are protected not only in O’odham law but by Arizona state law as well. Some of the cacti that were killed in the name of border security were over 150 years old, maybe even 200 or 300 years old—older than the geopolitical line that now separates the United States from Mexico. They knocked them down right and left.

In one way, it’s hard for me to understand how those who build this wall can disregard the life here. But in another way, I understand where this disregard comes from. So many in this country, including Indigenous peoples, have been uprooted—forcibly or by choice—from places, culture, and a sense of belonging. This lack of rootedness can make it harder to see other rooted beings as beings who deserve to live with integrity in the places where they belong. In an O’odham understanding, this community of beings includes the Saguaro, and the mud turtles, the onion and the spinach, numerous species of migrating birds, and the life-sustaining waters of Quitobaquito Springs.

The border wall rises behind Quitobaquito Springs, 2022.

Photo by Bear Guerra

Of course, it is not just the border wall that is impacting these beings; climate change has long been affecting this area. Extended periods of drought have put stress on the springs at Quitobaquito, and on neighboring farmers who rely on greater amounts of aquifer water to sustain their crops. As we come into this unsteady future together, we will count on new and existing environmental laws to protect the members of these interconnected communities. The language that these laws use will matter.

In 2021, our national legislative council approved a resolution affirming the legal personhood of Saguaro. When something is acknowledged as a person with rights, it is much more difficult to overlook the infliction of harm. This resolution has brought us one step closer to bridging our spiritual understanding of how to sustain life with the practices of the dominating culture. For better or worse, United States law is one of the few avenues available to us to protect the web of life in our wider community.

I’ve always believed in a higher power. As we sing, engage in ceremony, and do the work of writing and testifying on behalf of those who do not speak with human voices, we don’t expect miracles—but we always give thanks for them when they arise.

When the new administration halted construction of the wall in 2021, the water level at Quitobaquito was rising again within a month. Even though the pond is not yet up to full capacity, we’re thankful.

Quitobaquito may never be a thriving community again, but we hope to clean it up. We hope to plant trees and medicinal plants. We hope for it to be a place where many different communities can visit and learn, and where many species can find a home. We hope that if we nurture those seeds, they will come up from the ground and nurture us in return.