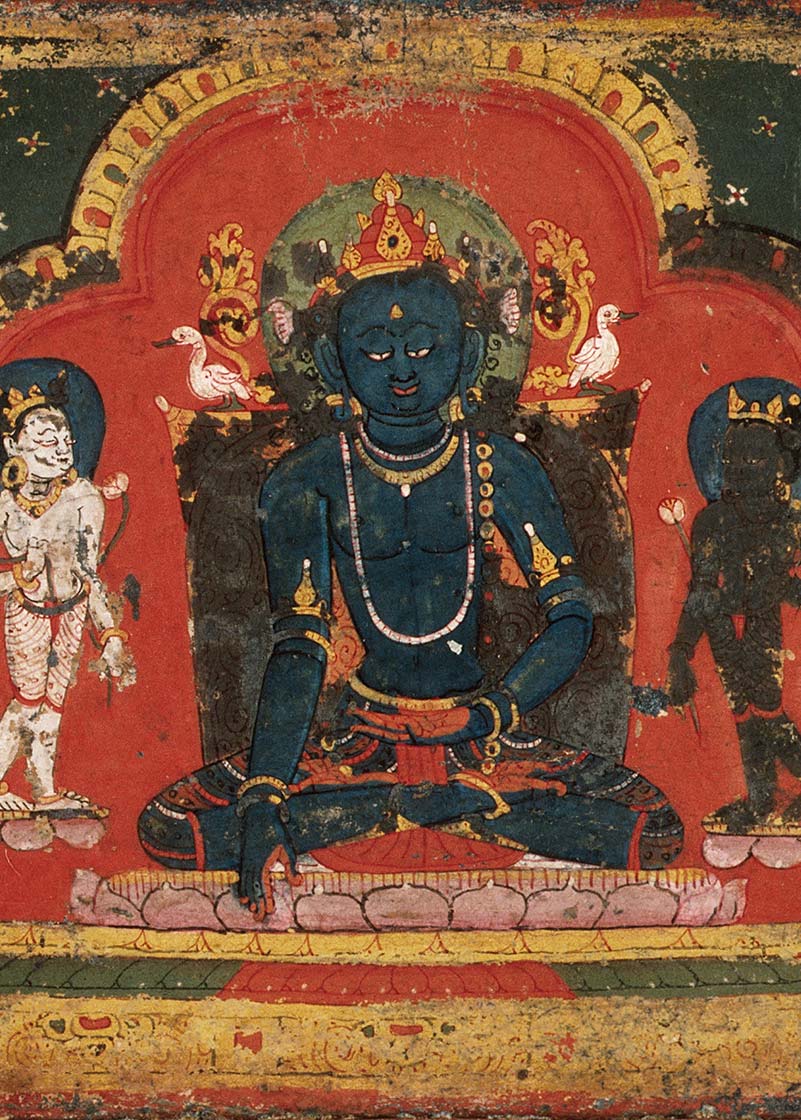

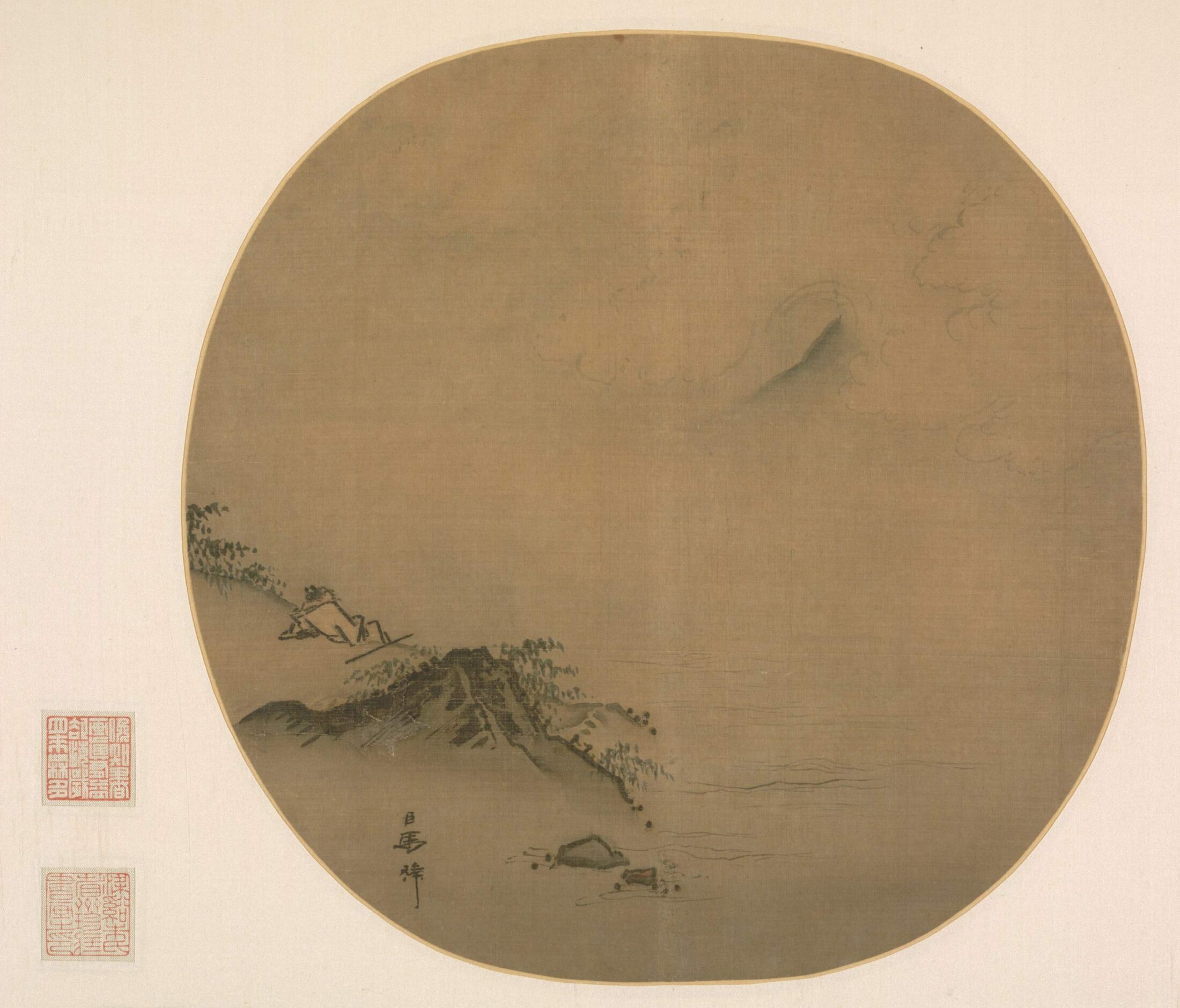

Ma-Lin, Scholar Reclining and Watching Rising Clouds, Poem by Wang Wei, 1225–75.

The Cleveland Museum of Art

A Ghost’s Life

Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee is a Sufi teacher who has specialized in dreamwork and Jungian psychology. He is the author of numerous books on Sufism and spiritual responsibility in our present time of transition, including For Love of the Real and Seasons of the Sacred, and editor of the anthology Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth. His most recent book is Seeding the Future: A Deep Ecology of Consciousness.

Responding to our fractured sense of reality, Sufi teacher Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee looks to the wisdom of the Ch’an Buddhist masters to help us find balance and belonging through direct experience of life’s wholeness.

Into what landscape have we stumbled, where the air is toxic with disinformation and social media distortions, algorithms intensifying divisiveness and tribalism? We know the power of propaganda, whether it comes from democratic governments or authoritarian regimes. We have always been fed lies by those in power, who use the media for their own purposes. But this present miasma has a different intensity and effect, as poisonous as the air of a pandemic. It is as if the very fabric of our consciousness has become distorted, creating not a fairground hall of mirrors but a dark web of conspiracy and deceit that sees truth as a primal adversary.

In this online wasteland nothing seems to grow except anger and acrimony. It is like a landscape inhabited by zombies, always demanding more attention, never satisfied, never fully alive. Whether the stories in this wasteland are of stolen elections, the dangers of vaccines, or other conspiracies, they all seem to image a world turning against itself, voices echoing as they become more strident. These stories appear to arise out of some field of disinformation, trying to catch our attention, wanting to be shared, retweeted, until, lacking real substance, they often dissolve back into our dark collective imagination.

Disturbingly, these distortions that surround us seem to be without a certain human quality that is not just a lack of care or understanding. While they may often be full of anger and oppression, they have the quality of being computer-generated, lacking any feeling of real tears, real passion. It is as if our whole human family has become infected by a virus or malware. Their words catch at our thoughts, our attention, trying to trap or seduce us. It is hard to feel their source in real suffering or searching. Are we caught more and more in some virtual world, where nothing is grounded in what is simple, human, and true, where everything is photoshopped into beauty or terror, the more extreme it is, the more clicks, likes or dislikes?

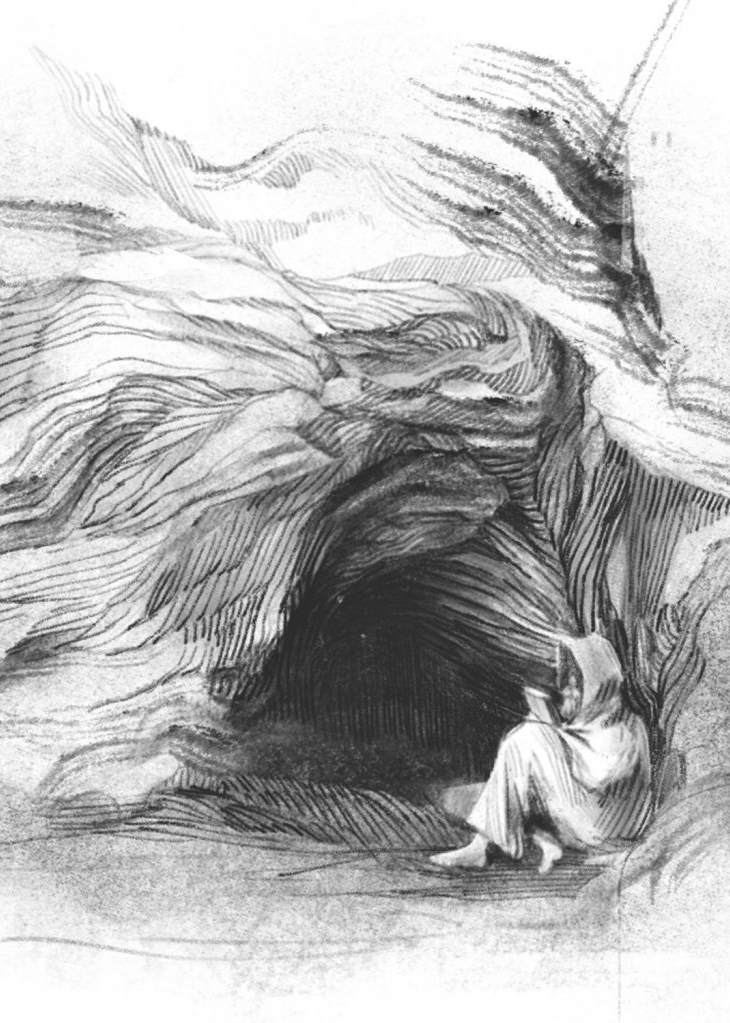

And what does this mean to our collective story, our shared journey together, whether through this present pandemic or into the coming disaster of climate crisis? How can we find the ground under our feet in this swirling fog of disinformation, where nothing is real except this manipulation of our attention? How have many people become so alienated from any real sense of community or belonging that their only home is in conspiracy theories? This contemporary feeling of living as a rootless exile in a broken world is aptly described in the Chinese Buddhist text No-Gate Gateway, a koan collection from 1228 CE, as living “a ghost’s life, clinging to weeds and trees.” This Buddhist text suggests that the “ghost’s life” is due to our being “radically separated from the vast outside of empirical reality, together with a suspicion that it needn’t be this way, that some kind of immediacy and wholeness is possible.”1 While one can recognize the world of internet memes being outside of any tangible “empirical reality,” the more vital question is whether today there is an open gateway to return us to a direct experience of life’s wholeness. Or will we drift further and further into this rootless viral world?

I feel I am living in a world that is becoming radically separated from any ground of being, inner and outer air made toxic. I watch these stories swirl around and wonder if they are just the nightmares of a civilization that has lost its way, soon to be forgotten as the dawn comes. Do they have any relationship to the real stories of this moment in time, or are they just patterns of denial to distract us from the failures of our culture, with its increasing divisiveness, racial injustice, and the primal tragedy of our dying ecosystem?

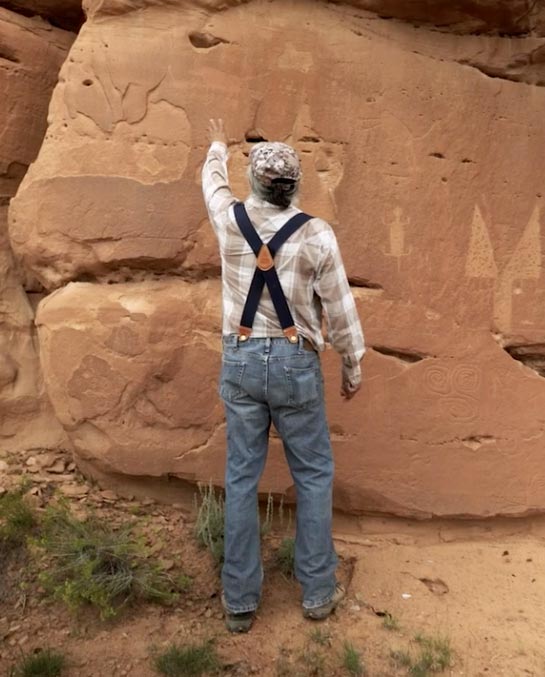

I am fortunate to be old enough for my consciousness not to be caught in social media, and I admit it is not a reality I fully understand. I enjoy seeing pictures and videos of my granddaughter growing up half a world away. I appreciate its illusion of connection. But I need the simple human exchange with friends or neighbors, at the post office, the bakery, or the store. I like to touch a tree, feeling the rough bark under my fingers, sensing its roots deep into the ground; I like sweeping its leaves as they fall onto the driveway. This is the direct experience that I need to feel I belong, belong to the earth and the sky, to the fox I found walking down the path towards me. I prefer the sight of wild geese crossing a skyline to any images on a smartphone.