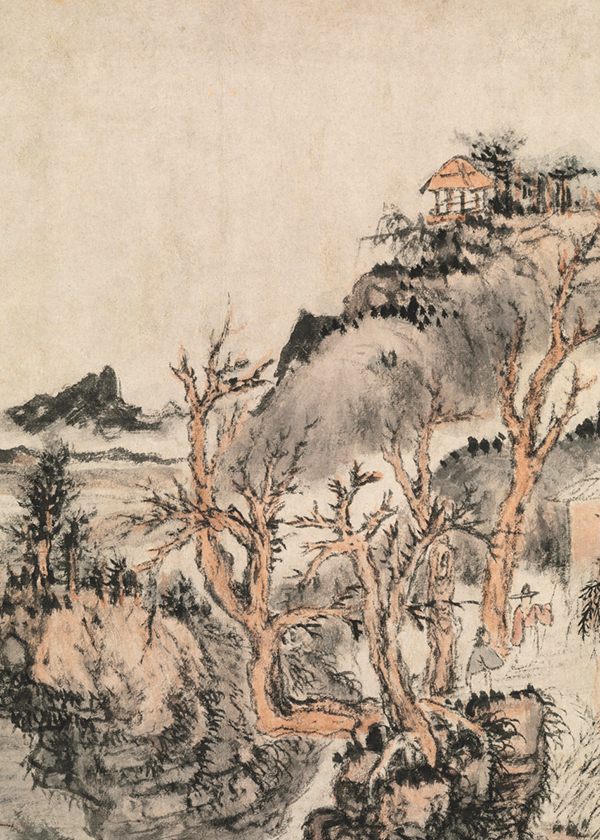

Photo by Dennis Stock / Magnum Photos

Darkness Rising

Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee is a Sufi teacher who has specialized in dreamwork and Jungian psychology. He is the author of numerous books on Sufism and spiritual responsibility in our present time of transition, including For Love of the Real and Seasons of the Sacred, and editor of the anthology Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth. His most recent book is Seeding the Future: A Deep Ecology of Consciousness.

In a time of growing ecological and humanitarian crises, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee bears witness to the darkness of the dying myth we are stranded in.

As our world appears to spin more and more out of balance, what are the stories that speak to this darkening time? What stories are destroying us, and what stories are sustaining us, helping us to find a path that can return us to a point of balance, a place of belonging?

The unprovoked invasion of Ukraine retells an old story of conquest and control bringing destruction and death. With missiles falling onto cities, thousands already dead, and over two million refugees, mainly women and children, fleeing, we are witnessing a way of life, of freedom, being lost. As these refugees join the millions worldwide displaced by conflict and persecution, this war is bringing the added threat of nuclear weapons and mass destruction—even as ordinary Ukrainians take up arms and build barricades to defend their country. So many lives shattered, dreams destroyed, darkness spreading. What is this world into which we have stumbled? Even while, for most of us, our daily life appears unchanged, our stores still stocked with food, our problems mostly personal, we are walking into a different landscape with few signposts for the future.

Meanwhile failure of leadership and our collective inability to respond to the reality of climate change is now confronting us with an accelerating disaster. The recent IPCC report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, reads as “an atlas of human suffering” with irreversible ecosystem damage, drought, fires, and floods increasing. For Africa’s Sahel pastoralists, the climate crisis has already destroyed a way of life that sustained them for millennia. They did not create carbon emissions, but with their cattle dying from drought they have become refugees in their own land. And their story is just a foretelling of the plight of hundreds of millions who will face water scarcity, floods, and famine as the temperatures continue to rise.

An imbalance in the natural world was also the most likely cause of the present pandemic, which showed the fragility of our global systems even as it brought anxiety over sickness and death and economic distress. And then what should have been a basic health concern morphed into conspiracy theories evoking aggression, tribalism, and a tangled web of misinformation. Is this simply a response to fear for loss of civil liberties, or is there another story hidden beneath these conflicting voices? Is something beginning to fracture at the roots of our society that is surfacing in this hostility?

Could it be that these images of a broken world speak with a wisdom we need to learn? That our present story—our dream of economic and material prosperity—is over? That underneath our intensifying divisiveness the Earth is telling us that conquest and control belong to a dying world? That our present way of life is simply unsustainable? And maybe we are not as cut off from the natural world as we imagine, maybe we feel in the depths below our rational consciousness how our present way of life is tearing at the fragile web of life that sustains us all. For centuries we have regarded nature as something separate, to be exploited for our greed and endless desires. But how can we be separate from the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the land that feeds us? There is a knowing in our bodies, even if censored by our minds, how we are part of one living ecosystem, which we are polluting and destroying at an accelerating rate.

Stories are what hold us together, sustain us, and give us a sense of belonging. But we have no story to support us in this present landscape, only a deep anxiety at what is being lost. Our politicians either project denial or, in some ways more dangerously, tell us that we can “green the economy,” continue with the fantasy of endless economic growth. Or they retreat into the bunkers of authoritarianism and nationalism, seeking both power and refuge in old stories that no longer speak to our present predicament. Meanwhile social media, which promised to bring us together in new ways, has accelerated our divisions, increasing the voices of anger. Is this what it means to live at the end of an era, in a post-truth world?

Young people are speaking truth to power, even as they cry out for a future that is being stolen and suffer the very real trauma of climate anxiety. They are more attuned to the moment than those in positions of power, recognizing how governments and big corporations are too addicted to the present ideology of progress and profit to effect real change. But while there are many suggestions for a more sustainable future—for example, rewilding, agroecology, reciprocity, degrowth, as well as the basic need for carbon neutrality—there is no story that speaks to our present condition. We are stranded in a dying myth, even as it creates ecocide in the world around us and under our feet.

When America was first “settled” by Europeans, 90 percent of the Indigenous population was killed within a hundred years: fifty-five million people died from violence and never-before-seen pathogens like smallpox, measles, and influenza. Recent research suggests that due to this rapid population decline, as farmland was abandoned and towns and villages were deserted and absorbed back into the forests and jungles, trees and flora captured so much carbon dioxide that the global temperature decreased, helping to trigger a period called “The Little Ice Age.” The land left unused in the sixteenth century created around 200,000 square miles of new forest, and by the end of the 1500s, the Earth cooled; winters became colder, extending far into spring; crops were devastated, resulting in famine. Colonization, pandemics, and climate change have been woven into the destiny of the planet, particularly that of America, since the beginning of European expansion.

Unlike the Spanish conquistadores, we cannot justify our present activities in terms of a religious mission to bring Christianity to Native peoples, even though some today justify their anger, even violence, as protecting their ethnic or national values. Instead of “God and gold,” we are mostly left with just “gold”—the basic greed that also underlaid the early colonists and the continued exploitation of nature and human beings that was a part of their conquest. European colonists helped create a world in crisis: as the Indian author Amitav Ghosh says, “The indigenous peoples of the Americas have been saying for decades that our past is your future and now that’s exactly what’s proving to be the case.”

We need to become free from the ideology of conquest, which seeks to control rather than listen, and sense what it means that the Earth is in distress and that our human landscape is fracturing. Sadly, much of our present ecological response is to continue with our technological dreams, fantasies of carbon capture or electric cars solving our carbon emissions. We do not dare to look deeper, to go beyond this story of conquest and control, of alienation from the land, of our failure to listen to its many voices. As Thomas Berry put it, “We are talking to ourselves. We are not talking to the river, we are not listening to the wind and the stars. We have broken the great conversation. By breaking the conversation we have shattered the universe.”

We can begin to see the effects of this primal split being expressed in our present divisiveness. We no longer have a living story, just profit and the unsustainable myth of economic expansion and the dynamics of power. And while there is talk about a new story—the eco-philosopher Joanna Macy speaks about The Great Turning, a shift towards a life-sustaining society—at present we are entering the space between stories, what Macy calls the Great Unraveling. How we walk this liminal landscape will determine much of the coming decades, whether we dare to recognize how our present story has become so environmentally and socially toxic.

For how long will we remain caught in a dying dream? If the present pandemic has evoked such anger, how will we collectively respond to the trauma of climate crisis? As fires, floods, rising temperatures, droughts, and climate refugees threaten our present way of life, where will we try to find refuge? Will our divisiveness escalate until we encounter social breakdown, even collapse? Will anger escalate into the violence that is at the root of so much of our Western colonial story, and is tragically once again visible in the war in Ukraine? Are we trapped in this cycle, or can we find another way to travel this landscape: in care, community, compassion for each other and the Earth? This is becoming no longer just a theoretical but an existential question.

I am fortunate to live close to the land here beside the ocean where I am surrounded by other stories, by the simple rise and fall of the tide, by a family of river otters I have come to know and love. Walking in the early morning wetlands, I look to see if they are swimming together, or tumbling over each other in the sand. A blue heron often watches nearby. These are stories that sustain me, even as our world seems to darken. They bring me solace and a sense of belonging. I would like to think that this time of transition is as simple as turning our attention back to the living land, being aware of its more-than-human inhabitants and how we are part of a single interdependent ecosystem. But I also know that the road back to this primal awareness that we mostly lost so long ago will not be easy. Our violence against each other and against nature continues to cast a long shadow. We have been sold too many false stories, separated from our deeper selves for too long. When we colonized the land and forgot it was sacred, we lost touch with an essential part of our heritage, with a loadstone that used to guide us for millennia. Today’s social landscape has few traces of this precolonial self.

Amitav Ghosh writes so poignantly, “The planet will never come alive for you unless your songs and stories give life to all the beings, seen and unseen, that inhabit a living Earth.” This is the world that is waiting for us, a fully animate Earth, alive with the songs and stories we tell our children and grandchildren: the true heritage we can pass down through the generations. We always belonged to this mystery, and maybe we can begin to find our way back, even if it means following an almost hidden path, unrecognized by our rational selves. Despite the growing darkness and images of destruction, the gate to this garden is always open, and if we listen carefully, we may hear the many voices that still beckon us.