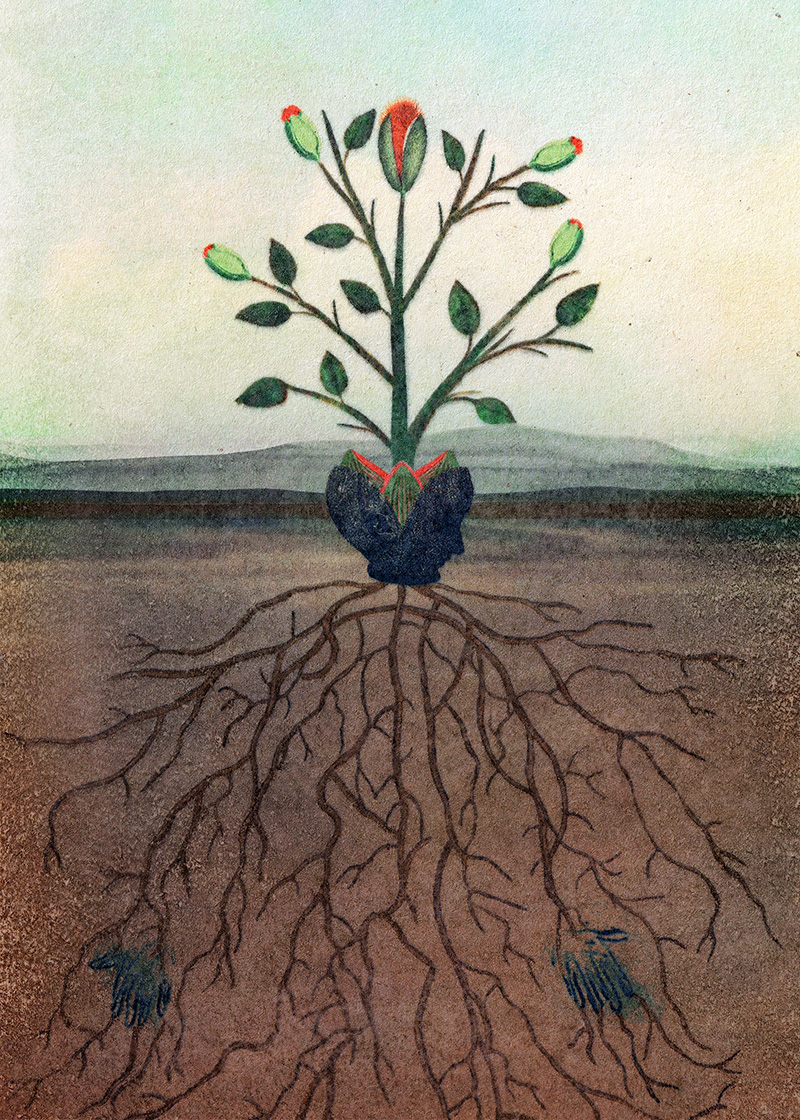

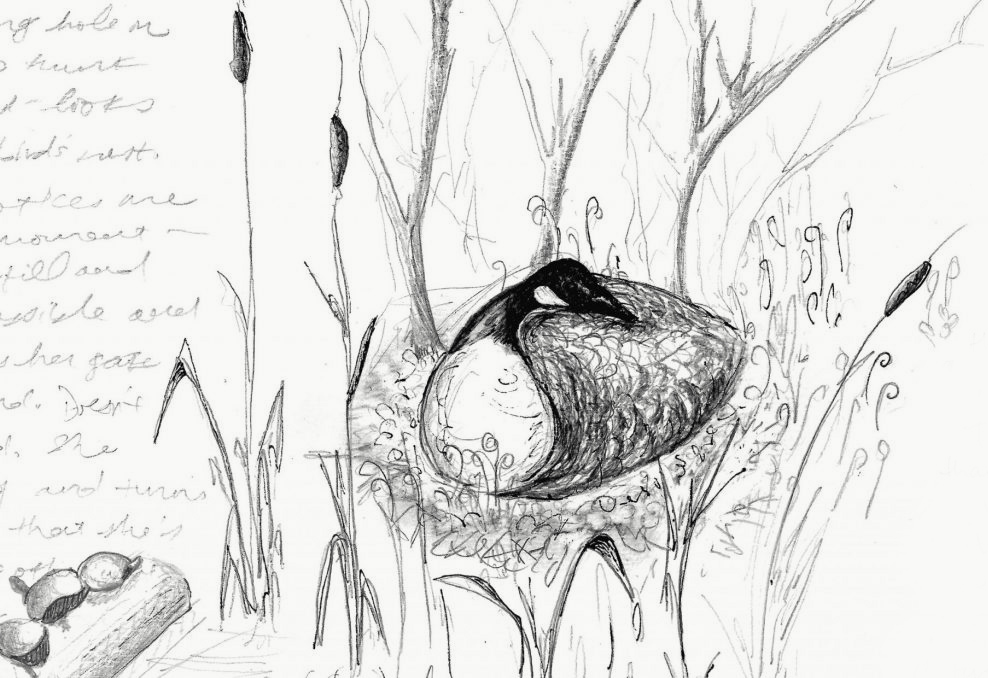

Artwork by Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder

Above Water

Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder is a writer based in northern New England whose work explores the human relationship to place. Her essays have been featured in Crannóg Magazine, Inhabiting the Anthropocene, and EcoTheo Review. Her forthcoming book is Rebirth: Mothering Through Ecological Collapse.

As she navigates the second trimester of her pregnancy in the midst of a pandemic, Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder looks to a Canada goose seated on a nest of eggs for ways to gracefully inhabit a shrinking world.

March 31

There is a small nature preserve near our house, made up of mature birch and hemlock trees and a two-acre pond filled with native cattails.

My husband and I have been walking here several times a week since the pandemic started; our usual trails are now overcrowded. Though the preserve is less than a quarter mile from a trafficked road and there are a number of houses that abut the boundary, it remains a quiet place.

We always bring binoculars and watch the chickadees chattering in the scrub brush or the downy woodpecker at work on the trunk of a tree. We’ve yet to come across any humans on this trail, which extends just a third of a mile, with the pond on one side, woods on the other.

Lately, we’ve made a habit of turning off the trail to step out onto a narrow peninsula that extends twenty feet into the pond. It’s barely five feet wide, built of spongy moss and damp grass. To get to the far end, we have to crouch or crawl beneath the young trees and bushes that have managed to take root on this strip of land.

Here at the edge, on the cusp of the water, is an oasis. The cattails grow free from the encroachment of invasive phragmites and Japanese knotweed that have elsewhere crowded into wetlands and marshes. Songbirds sway on reeds and turtles poke their heads above the surface. Ducks plunge their heads into the submerged weeds.

We are away from the news and out of view of the nearby houses. If the sky is clear, I roll up the bottom of my shirt and turn my rounding belly to face the sun. I take deep, clean breaths.

Lately we’ve been seeing another couple across the water. We keep our distance and they keep theirs. All of us seem to prefer silence.

They are Canada geese.

April 2

A warm sun is setting over the water. One of the geese is directly across from the peninsula, seated atop a small mound of grass and reeds, inches above the water. The early shapes of fiddleheads are curling out of the ground around her. Behind her is a shelter of reeds, shrubs, and tall golden grasses.

She is turning slowly in place, adjusting her stance and stretching her wings along her back. She sits and rocks herself a couple of times side to side and then uses her beak to arrange bits of down, tucking it carefully around her copper body.

I instinctively put my hand to my belly. She, too, is going to be a mother.

April 3

Last night I felt my child move for the first time—subtle and fluttering.

This morning, it’s raining lightly and the surface of the pond is soft with movement. The goose is seated on her nest, her long neck turned, her beak tucked into her back feathers. The gander is thirty yards away, standing in the shallows around the reeds.

I’ve been reading: Mothers generally begin to feel the fetus move between eighteen and twenty weeks. The movements are indistinct at first and hard to distinguish. Soon, I’ll feel them all the time, and my husband will be able to feel them too.

I’ve also been reading: A Canada goose makes her nest atop a slightly raised mound into which she makes a bowl-shaped depression. She will be near a water source, with an unobstructed view of what is around her. She lines the nest with cattail, grass, reeds, and down that she plucks from her own breast. She will lay between five to twelve eggs, over the course of as many days, and then incubate them for four weeks. The gander will always be nearby, keeping watch. They’ll defend the nest together if need be.

April 6

Friends tell me that I sound upbeat, like I’m doing well in the midst of all this. They’re mostly right—I’ve been keeping my head above water, staying calm, finding things to smile about. I try to keep the anxiety at bay by taking deep breaths, by limiting the news, by leaving the window open as the cold rain comes down with a steady thrum that feels like a cocoon.

The truth is, I don’t feel that I have much of a choice. My pregnancy books tell me that a fetus can sense their mother’s stress and worry. And so, since I have the luxury of finding ways to keep calm—I am not sick, I have a home and plenty of food—I have been.

It’s not that I’m in denial; I don’t think it’s ignorance. It’s more like an ongoing effort to joyfully inhabit a shrinking world: my home, my husband, this growing baby, and the edge of this peninsula where I have a view of the only other mother that I can visit, sit with.

At the pond today three great blue herons fly overhead, long necks bent to their chests, wings steady. I’ve never seen three together before, in the sky or in the water. Below them, the goose is quiet and alone and on her nest, as always. How small her world is! How gracefully she inhabits it.

April 9

I want to see my mother and my friends, show them how my belly has grown. I can’t, and it’s lonely.

I learn that the number of confirmed novel coronavirus cases in the United States has reached nearly half a million, a number which will be painfully outdated by the time you are reading this.

I have my next prenatal appointment in several days; the nurse called and told me to come in with a mask on. They’ll take my temperature in the lobby. I think of the mothers who have had to give birth alone, without their partners and spouses by their side.

The day’s heavy rain turns to heavy snow as the sun sinks behind the gray sky. There’s an inch of icy white on the ground by the time I go to bed, and it’s still coming down fast.

I think of her there without shelter in the dark, snow collecting on her back.

April 10

The storm has passed. There is a paper-thin skim of ice over the pond in the places that have yet to meet the rising sun. The goose has her neck stretched in front of her, prone on the ground. Her eye is unblinking. The gander is nowhere in sight.

I hand the binoculars to my husband. “It doesn’t look good,” he says, and I feel a knot in my stomach. I wonder if the water is shallow enough for wading across or if we could bring one of the kayaks here to retrieve the eggs, if they haven’t already gone cold.

But then she raises her head and looks around, tucks her beak into her back feathers.

April 11

I pass the gnarled, old white pine at the foot of the peninsula and crawl along the damp ground to the edge. I sit here, hands on either side of my belly, and watch her, thirty feet away. Both of us in the sun. Both of us quiet, both doing our needed work, in needed solitude.

An hour later, I arrive back at home.

“How was she?” my husband asks.

I hang my jacket and binoculars on two hooks by the door, remove my shoes, and step into the warm kitchen.

“She was good,” I say. “Content.”