Practical Reverence

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, scientist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants and The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Robin is a MacArthur Fellow and was awarded the National Humanities Medal. She lives in Syracuse, New York, where she is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this conversation, Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer introduces us to the serviceberry as a living model for a gift economy that recognizes the sacred nature of the Earth. Speaking about her latest book, which elaborates on an essay she wrote for us in 2020, Robin offers a framework for embodying a practical reverence: an ethic of care, reciprocity, and gratitude for the Earth and Her abundance.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeRobin, it’s such a pleasure to be in conversation with you today. Welcome.

Robin Wall KimmererThanks for inviting me.

EVI’ve just finished your new book, The Serviceberry, which grew from an essay you wrote for Emergence that was the most read essay we’ve ever published—which I think points to the chord it struck with people. And this new book expands on this essay and is not only a wonderful celebration of the generosity of the land, but is a really powerful manifesto on abundance and reciprocity as models for a new economy that operates in right relationship with the Earth. But before delving deeper into that, I wondered if you could introduce us to the book’s namesake, the serviceberry. Who is this plant and what kind of relationships do we have with it?

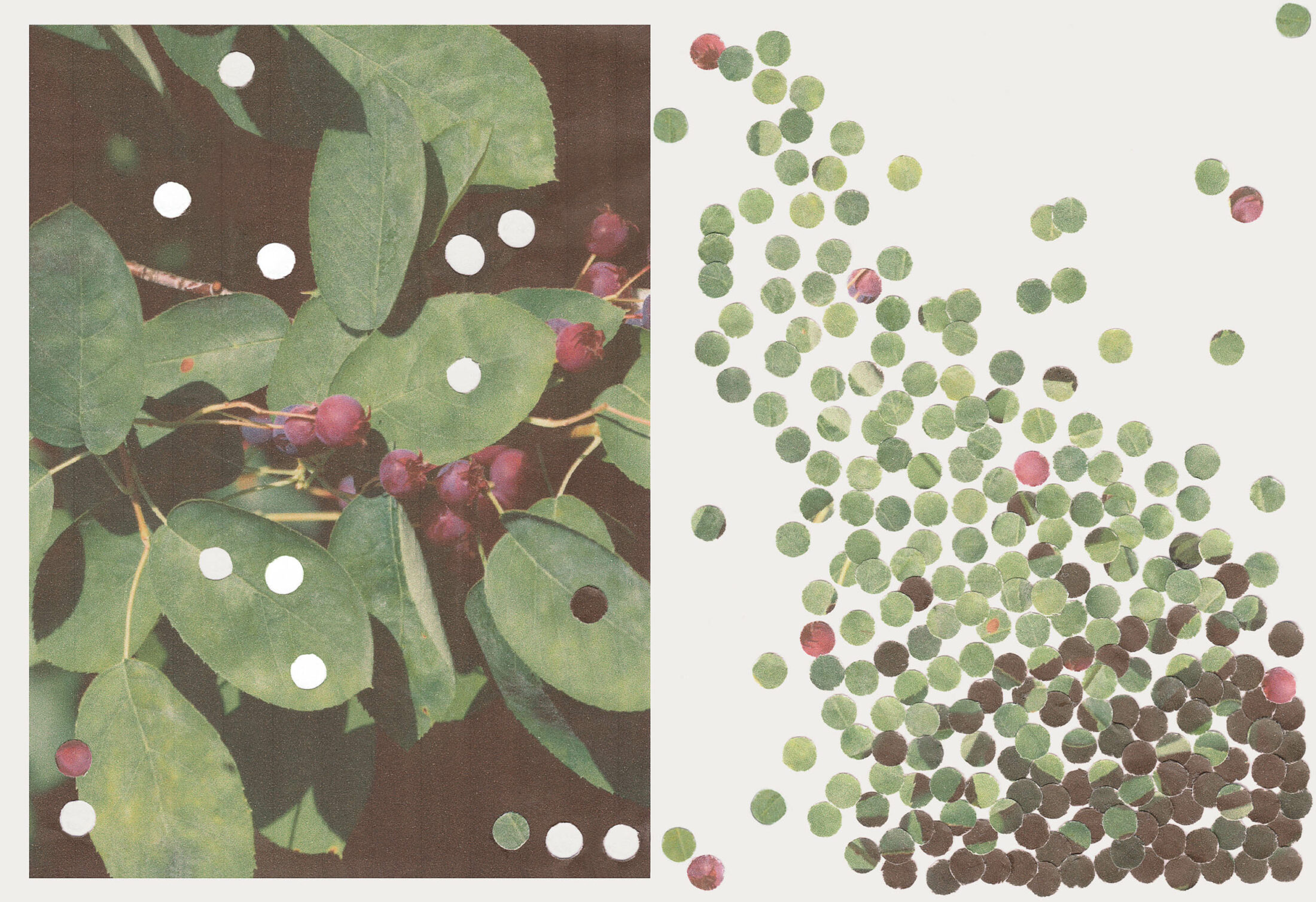

RWKI’d love to start there. The serviceberry is a plant with so many different names: juneberry, saskatoon, sarvis, shadblow, shadflower. It has so many names because it has so many relationships. And if you were to meet a serviceberry that would likely be along a wood’s edge, near water. It’s a small tree, a little bit shrubby in nature, and in a way, quite unremarkable looking, just oval leaves, smooth gray bark. You might just walk by it without thinking too much about it, unless it was springtime, in which case there’s just this explosion of bloom before anything else in the woods is in flower. So some of its relationships are associated with those early spring pollinators. In July or June, depending on where you live, there are these heavy clusters of delicious berries that hang from the branches. And then it surely draws your attention. And even then, if you missed it, the cedar waxwings and the robins would let you know, because they’re just calling and chattering and saying, Berries, berries, berries. Everybody, come feast. So your attention would be drawn when it’s in fruit.

EVIn the book, you share that in the Potawatomi language, the word for serviceberry is a revelation, because it is also the root word for “gift.”

RWKYes. That little word min means “berry” in my language, but it is also the root word around gift-giving, and around a gift. And I love the poetry of that, because, of course, berries feel like a gift, don’t they? There they are just presenting themselves, hanging there all red and blue and sweet and juicy, and we didn’t earn them. We don’t deserve them. We don’t own them. And yet there they are, like an offering from the tree. And so I love that that’s present in our language as well.

EVBerry picking is a hugely seasonal act, and it is for many a ritual of the warmer months that embodies the gift of summer. And across your work, and particularly in The Serviceberry, you write about how abundance and the summer proliferation of berries and flowers, fruit and vegetables, leads us to characterize this season as one of deep abundance, of plentifulness, although this notion of abundance can be found and felt across all seasons in different ways. And in The Serviceberry you reorient us to look at this seasonal abundance differently, introducing us to how it can be pivotal in reimagining an economy that is currently based on scarcity. I wonder if you could speak to this.

RWKYou know, in fact—back to the language—our word for summer, niben, means the time of plenty, it means the time of abundance. And the notion of abundance being provided by the plants is, to me—I think about it not only in berries, but in medicines for us, in materials for us, basket plants, all the kinds of things that the plants, by virtue of the ways that they live and the surplus that they create, creates abundance for us if we know them, if we know their gifts, if we are paying attention to them. And I like what you said, that it’s not just in the summertime: even in deep mid-winter, the plants are offering us medicines and teachings and materials.

EVIn the book, you point towards a need to shift our ideas on consumption: we need to learn to see that most of the time we already have what we need. And you write that recognizing enoughness is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more.

RWKYeah, for sure. You know, think of all the messages that we get relentlessly from media, from advertising, saying: Well, you know, if you only bought this, then you’d be happy. You need to consume this. In fact, our very measure of a successful economy is one that is always growing, which means always consuming more. Right? Whereas the notion of enoughness— Doesn’t it just make you feel content to think of enoughness? To say, I have what I need. I have everything that I need provided for me by the land. And to me, that just awakens gratitude and a sense of sharing, of saying, I have enough. And so that means if I have enough, the rest, the surplus, can be shared. And that notion of enoughness as a radical act really can put the brakes on consumption. And we know that it is hyperconsumption that has us poised at the brink of climate catastrophe. Right? And so it’s not only a radical act in an economy, it’s a real act of healing for the land and for people, as well, to say: I have enough. I don’t need to take any more. Which then liberates that abundance for others so that they can flourish too.

EVWell, what you’re talking about is radical, particularly in the framework of the capitalist economy that we operate in. It also isn’t, in many ways, because this way of living in accordance with abundance and an ethic of sharing has been around for millennia practiced by cultures that live in close relationship with the land the world over. And in both The Serviceberry and Braiding Sweetgrass you talk about a canon of principles that govern this practice in many Indigenous cultures, including your own, called the Honorable Harvest. Could you talk about this?

RWKThe Honorable Harvest is— Well, I want to back up and say thank you for recognizing that this isn’t new and radical. These are in fact the fundamental principles of how one lives sustainably in place, which we have forgotten, which we have been made to forget by an economy that doesn’t want us to have enough, that always wants us to consume more. And in order to talk about the Honorable Harvest, what I also have to talk about is that the stuff that the Western extractive economy wants us to consume is understood as material. It’s just stuff, right? It’s objects. And so if we’re just consuming objects, and if those objects belong to us, if they’re our property, we don’t really need any ethical guidelines about consumption, because it’s just stuff.

But in the Indigenous worldview that views those plants, those animals, Mother Earth, as our relatives, right, as our kinfolk, we are now talking about in order to live, we have to eat our relatives. Right? Now that opens up, not natural resources, but our relatives, our kinfolk, who are giving us gifts. And so that creates both a pragmatic and an ethical imperative to have guidelines that regulate how we consume. And so those are what are known collectively as the Honorable Harvest. And the Honorable Harvest guidelines begin— They were taught to me in picking berries and digging medicine roots, et cetera, you know, sort of piece by piece. We’re always taught responsibility before we’re taught the taking. Right? And the Honorable Harvest begins with the fact that we never take the first one; whether it’s berries or firewood or basket plants, you never take the first one. And this self-restraint means that you’re never going to take the last one. So it has an inherent conservation ethic.

And, you know, different cultures have different ways of thinking about it, but sometimes the rule is you don’t harvest until you see four, or you see seven, or you see ten, whatever your family’s guidelines might be. And then, you never take more than half, because you always have to leave some for the thriving of the plant, but also for the other ones who, the other beings who want and need berries or medicines too.

When we see the fourth one, let’s say we also ask permission of that plant. I will quite literally introduce myself and say— In fact, I was just doing this the other day, harvesting some mosses for my upcoming Ecology of Mosses class. And I had to talk to those mosses and tell them, you know, would you come into my lab and teach my students? Is that okay? And that step of asking permission recognizes the sovereignty— It recognizes that the plants don’t belong to us; they belong to themselves. And so if we’re going to ask permission, we have to listen for the answer as well. And there are a lot of ways to do that. We can use Western science to do that and look at the demographics of the population. Look at its health, look at its vigor, look at the soil quality. Is it thriving? And if it is, you say, well, yeah, I think they have enough to spare. But if it’s weak, if it’s chlorotic, if there aren’t any young ones, you would say, no, I can’t harvest here because this population doesn’t have enough to give.

But if it does, then as I said, you take only half, and less than; you take only what you need. And you take it in such a way that you do as little harm as possible. Don’t disturb the whole place in order to get what you need. It’s a long protocol for picking berries, for taking from the Earth, as opposed to the Western mode of going in and just grabbing what you need. Right? Well, when you harvest, you, again, take only what you need and give thanks. You stop and pay gratitude to those plants, because, after all, they’ve just given you their bodies, in some cases their offspring you’re taking home in your basket. And so you really pay gratitude, not just in that sort of flip thank you, but a real recognition that your life is inextricably tied to theirs. So a deep kind of gratitude.

And then, I’m told that we never go home with our basket without reciprocating the gift, of giving back to those plants. We’ve taken something; they’ve given us something. So how will we pay them back? Sometimes it’s with a spiritual gift. In fact, it’s always with a spiritual gift, but also a material gift: Maybe they need a little more sun. Maybe you should weed around them. Maybe you should sprinkle some fertilizer there if they’re looking like they need it. So you need to know the plants; you need to know what they want and to help them out. And then, you have done right by the plants. It is an Honorable Harvest because you have been given what you need, you haven’t done serious damage—and, in fact, some of the ways that we’re taught to harvest actually help the plants to multiply. If that reciprocated gift is, I’m going to carry some of these roots to another place where that plant could flourish, well then, I’ve just used my gift of mobility to complement the gift of the plant making medicine. So oftentimes the ways that we harvest actually multiply abundance.

EVYou’ve previously written that this knowledge has continued forward in stories, and that these stories help us to restore balance and locate us once again in the circle. Can you speak a bit about this circle?

RWKThe circle that I’m referring to is a circle of mutual flourishing with our kinfolk. These stories remind us that the Earth doesn’t belong to us, that we are blessed to receive the gifts of the Earth, and then we have to give our gifts back in return. That’s the circle, right? It’s a circle of giving and receiving that recognizes that everybody in the circle has a gift. And it’s our responsibility to use whatever our gift is to support the flourishing of our kinfolk leafy ones, the feathered ones, the furred ones.

EVThroughout The Serviceberry you refer to a concept or way of thinking that understands the currency of the gift economy to be relationship, which you express perhaps most directly in the line, which is repeated throughout the book, “I store my meat in the belly of my brother.” And I love this line. Could you talk about this?

RWKIt is the heart of the book and of the essay, isn’t it?

EVYeah.

RWKIt comes from the explorations of a linguist who was working in Amazonia with Native peoples there. And in his reports, he tells this story that a hunter and his family were really successful on a hunt, and they brought back some big game. And as they were preparing it, the anthropologist and the linguist who were observing said, well, you know, what will you do with the surplus? How will you store it? Because clearly it was way more meat than the family could consume. And so the hunter said, “Store my meat?” He didn’t quite understand it. And the interviewer said, “Well, you know, dry it or smoke it, or put it away for a time when you need it.” And the hunter said, “I store my meat in the belly of my brother,” meaning he had a surplus, he had an abundance of food, and so he was holding a feast. And all over the village, all his family and friends and neighbors were all invited to come partake of that feast. So the storage of that meat was in good relationships, in the feasting, in the storytelling, in the singing that accompanied his sharing the gift of the forest with the people.

And this notion of, I store my surplus in the belly of my brother, means, of course, that you’re creating relationships of reciprocity and that those reciprocal relations manifest themselves in food security down the line, because there’s going to be a time— Abundance isn’t guaranteed, right? There are going to be scarce times too. And in those scarce times, you then have the sense that the people who came to your feast will share with you. When they have a big net full of fish, you’re going to be invited to their feast. And so, the food security comes from good relationships with your neighbors and a trust that abundance will always be shared.

EVYou write about how our current economic model is rooted in projects of colonization and how the dispossession of Indigenous people was designed to eradicate the notion of land as a source of belonging and to replace it with the idea that land is nothing more than a source of belongings, which you pointed to a little bit earlier. And that this, in turn, narrowed the definition of well-being from commonwealth to individual wealth, and from abundance to scarcity, which really gets to the heart of the crises that we’re experiencing.

RWKYou know, the idea that the land is a gift that we can only harvest honorably, that we hold land in common, not as individuals, runs completely counter to the Western notion of property law and prosperity, right? Where the gifts of the land go to make individuals prosperous and wealthy as opposed to the whole community. And in this country, that was a very dangerous notion—a notion of colonizers, particularly colonists who came to North America expressly for land. That’s what they wanted. So the notion that land should be held in common, held as sacred, was a dangerous notion.

And so when we look at the projects of violent assimilation, through the boarding schools, for example, and other tools of cultural erasure, much of that, including the erasure of our language—attempted erasure of our language—was in large part to replace, in this imperialistic way, the notion of common land with the notion of private land and private property. This enables the commoditization of land, the commoditization of forests and water and wildlife, so that the benefits all accrue to individuals. And now, of course, corporations are viewed as persons as well. So that falls under that umbrella as well. But yeah, basically what we’re talking about is the replacement of the Indigenous view of commonwealth with the notion of private wealth.

EVYou talk about how the equations we use to measure economic value, like GDP, only account for that which can be bought and sold. And there is a great line in the book that speaks to this: “There is no room in these equations for the economic value of clean air and carbon sequestration and the ineffable riches of a forest filled with birdsong. Where is the value of a butterfly whose species has prospered for millennia and lives nowhere else on the planet? There is no formula complex enough to hold the birthplace of stories.” I was very moved by that line, and especially the last sentence: “There is no formula complex enough to hold the birthplace of stories.”

RWKYou know, economists, particularly ecological economists, are trying to quantify the values of clean water, air quality, forests, et cetera, through this language of ecosystem services. And the idea is that if you could put a monetary value on ecosystem services, then you could factor them into that equation. And so there’s absolutely merit in that way of thinking. But the problem is when we try to put economic valuation on birdsong and water, it converts the gift to commodity.

EVRight.

RWKBy monetizing it, it takes away from its inherent value. It says that the value becomes the dollars associated with it, not its intrinsic, indeed sacred, nature. And so there’s quite a bit of resistance to valuation of ecosystem services on philosophical grounds, but it’s also true that it is an attempt to put those things back in the equation.

EVI want to talk a little bit more about the notion of gift, which we’ve touched on already, because this model of harvesting only what you need to live is really an example of a gift economy. And I wonder if you can talk a bit about the sorts of ethical constraints a gift economy encourages around the accumulation and distribution of things.

RWKSo the ethical constraint around not converting a gift to a commodity, to me, is best exemplified in thinking about water. You know, if maybe when you turn your faucet on, you just think it’s this fluid that’s coming to you from public works. But if you focus on really understanding what’s coming out of your faucet, you know, that beautiful water—finite in quantity, right, we will never have any more than we do today—that falls freely from the sky and waters our gardens and makes food grow and makes flowers bloom. This water that can be dew, it can be clouds, it can be snow, this long traveling molecule that animates life all over the planet, without which life simply would not exist. Oh, now you start looking at water and saying, it’s a lot more than this clear substance flowing out of my faucet. It’s not an object anymore. It is a gift.

And so when you think about this gift of water, it belongs to all of us. The rain falls on all of our heads, right? So why does a corporation have the right to say, this freely distributed gift I am going to filter and put into plastic bottles and sell at a price that’s higher than gasoline? That they’re going to make all kinds of money over a freely given gift—that seems an ethical travesty.

EVRight.

RWKAnd, of course, think of all of the environmental damage that is done by privatization of water, in single-use plastics, et cetera. But to me, the real crux of that is that water should be a public good, a common good, and not privatized. So that’s just one example of thinking about what feels to me like the ethical jeopardy of privatizing a freely given gift.

EVYeah, you write that “to name the world as gift is to feel your membership in the web of reciprocity,” which really challenges what you just described as the way we currently perceive water, for example.

RWKYeah, exactly.

EVYou look at the serviceberry plant itself as a model of gift exchange, looking at how it participates in hundreds of gift exchanges before you even put a berry in your mouth. The plant is accepting things from different parts of the ecosystem so that it can grow, and giving many other parts of the ecosystem what they need in return. And you speak about how this is a big part of the gift economy ethos, keeping the gift in motion so that it does not stagnate.

RWKYeah. When we look at the economy, if you will, of the serviceberry, it’s a circular economy. It’s an economy in which the production of that wonderful plant is in circulation. It’s not hoarded. It’s given away from the pollen on those beautiful, frothy white flowers in the springtime that feed those early season bees. Right? It’s given away. When we think about the foliage—those beautiful solar panels of the leaves that are fueling the growth of that tree, that are the sole food for certain kinds of caterpillars—that production is being given away, as it were, released to those caterpillars. When it comes time for the ripening berries, everybody shows up—all the birds, all the small mammals and the people too—to share in this abundance. So the plant is making these baskets full of berries, and they’re all heading out in all kinds of other directions. Not to be accumulated, but to become part of life: to make more birds and more birdsongs and more meadow voles and jumping mice and everything up and down the food chain. And then when fall time comes, the leaves fall to the ground and feed that whole web of the detritivores that make the soil that allows more serviceberries to grow. And so it’s a circular economy. Everything that is made is given away, is sent off to support other lives. But then those lives support the serviceberry. And so it is a model of circulation and circularity.

And we know that these circular regenerative economies are the ways that nature provides abundance. And, for the most part, our industrial economies are quite the opposite. They’re just these short industrial pipelines that go from production to waste with amazing efficiency. But in a natural economy, there’s no such thing as waste: a waste product becomes a resource for someone else’s life. And in that way, I mean, the whole point of the book, right, is this idea of biomimicry. Could we look at how nature delivers goods and services in this regenerative way? And why is it that we don’t create our human economies to emulate nature rather than to wreck nature?

EVYou say that in response to gifts, our first intuitive response should be gratitude. And it’s not quite as surface level as manners. It’s not the simple vocalized thank you that we are often accustomed to. It’s more about a recognition of indebtedness that brings you into the realization that your life is nurtured from the body of Mother Earth. Can you speak a little bit more about the recognition of indebtedness that lies at the heart of gratitude?

RWKYeah. And that’s what converts it from just this ritual of nice manners, to say, thank you. It is the recognition that our lives are intertwined. That our physical lives are intertwined. If not for you, I would not live. And so that’s a powerful kind of gratitude, right? To say, you know, without you, I could not be. And really what it takes is that attention and a kind of humility, the beautiful kind of humility, not— You know, oftentimes in the Western world that idea of humility comes to mean a kind of meekness or self-effacement. But in the teachings that I’ve been given, humility—in Potawatomi language the word is edbesendowen—means the recognition that I am not more important than you. Which doesn’t mean that I’m not important. It means that you’re important too, that we are important to each other. So it’s a way of lifting up all lives to say we are all important to each other. Without each other, we would not be. And that’s a really deep kind of gratitude that makes you feel so fortunate. Right? And it creates a really different orientation to the world of, not that I’m going to try to take more, but that I’m going to respect what has been given to me.

EVYou echo this thought in Braiding Sweetgrass, writing that the expression of gratitude for what the Earth gives us is revolutionary in a consumer society. That contentment is radical. Gratitude creates an ethic of fullness, and we live in an economy that thrives on emptiness.

RWKYeah, exactly. And that’s why the notion of gratitude, enoughness, and abundance feel so important as an antidote to the endless need to consume. The idea of contentment. And we’re back to the notion of enoughness, aren’t we?

EVYeah.

RWKThat just makes you say, I have everything that I need.

EVYou also say we need to go beyond gratitude and that we need to become a culture of reciprocity. What do you mean by that?

RWKYou know, gratitude feels like we are expressing our thankfulness for our lives, et cetera. But then, you know, when someone gives you a gift, you want to give them something. You are in their debt, in a way, and you want to honor them and respect them in the way that you’ve been respected. And so that opens the door to reciprocity, to say, well, what is the gift that I could give you in return for water or berries or birdsong or whatever it is that we’re talking about? And that requires that deep self-examination to say, well, what is my gift? And which of my gifts are what the world needs in this moment? And now we’re talking about a purpose-driven life, right? To say, oh, I matter too. I matter too. My participation, my gifts, need to be in the world in order for the world to thrive. And then that converts our sense of ourselves far beyond just a consumer, right? We’ve been sold this narrative that we humans are just takers, that we are just consumers, that’s all that we do. But in reciprocity, we can reclaim our sense of ourselves as givers, as well, as full participants in the flourishing of the world. And that’s joyful. It gives you a sense of kinship and purpose and agency that rivals this sense of agency and purpose that the birds and the trees have.

EVAs the currency of the gift exchange, gratitude and reciprocity are a truly renewable resource. And you write, every time gifts are given, their energy concentrates as they pass from hand to hand. Can you speak a little bit more about what you mean by this and what is enlivened within both the giver and the recipient in this exchange?

RWKThere’s some beautiful writing around this in Lewis Hyde’s beautiful book The Gift, and other philosophers and anthropologists talk about this. But let’s take the example of a gift like—supposing I wanted to just give you a teacup, I could go down to the local store and buy a teacup and give it to you. But what if the teacup that I gave you was my great-grandma’s, that she brought with her from a long journey, that she had told stories and had tea parties? They’re both vessels for holding hot water, but one of them has been exchanged so many times, has so much more resonance, so much more meaning, so much value and honor. And that’s the way that relationships kind of burnish the gift and make it even more valuable. And if you then took that gift and gave it—said, this was given to me by Robin in honor of our friendship, and she gave me this one that was in honor of her grandmother—all of that story keeps going, right? And so the gift as it is passed on, in the sense of a material gift, gathers the nonmaterial value and stories that go with it. In an ecological sense, gifts also get in a sense more concentrated when they go up the food chain.

EVRight.

RWKAnd that’s the other element of thinking about ecological gifts, that you think about, perhaps, say plants that are harvesting abundant sunshine. But when they make berries that are then eaten by the birds, the birds are only concentrating about ten percent of the energy that the tree produced in those fruits. And so the birds are a more concentrated form of that energy. And whoever eats the bird, the fox that just picked that robin off the ground, is getting ten percent only of that. So now it’s a hundredth of what the plant produced. And so, as you go up the food chain, energy also becomes much more concentrated. And that’s another way to think about the way that, as gifts are passed on, they become more valuable. I mean, it’s why there are fewer birds in the world than grasshoppers, because that energy is concentrated. That gift becomes in a sense more valuable as it is passed up the food chain. So it’s both cultural and ecological.

EVYeah. I liked what you said about how the material gift holds the story as it is exchanged when given to others. And it makes me think about also the spiritual exchange, the energy that’s present within the story that is allowed to become more concentrated as it is used and enlivened as the exchange is passed on. And that when we stop it by saying, no, it’s mine, it’s like we stop the flow of everything that’s happened until that point.

RWKAbsolutely. Right? Yep. Exactly.

EVOne of the main questions now being asked in relation to the gift economy model is, how do we take it and scale it up so it can be feasible within societies at large? But you challenge this notion and you say that you’re not sure that’s the right question, because it is the small scale and the community context that makes the flow of gifts meaningful.

RWKYeah. A lot of the scholarship around gift economies all over the world—and they occur all over the world. They occur in small, close-knit communities, and there’s a very good reason for that. Gift economies rely on trust. They rely on being known. They rely on saying that, you know, you invited me to your feast, so I’m going to invite you to mine. In a society which is too big and too complex, you can be anonymous within the society, right? And anonymity creates the opportunity for cheating in the system. But where everybody is known and related through gift exchange, there’s a high level of trust. So this diffuse reciprocity can work.

And so it could be said, well, gift economies then can never prevail in a society like in the United States today. But I don’t think that’s true, because what we as individuals crave is community and a sense of belonging. So gift economies are not going to replace extractive capitalism, right? But I think they can exist within it as we create and value these small-scale communities. And we saw that happen during the pandemic as mutual aid societies in neighborhoods grew, as community gardens grew. People found ways to create these small, very local webs of reciprocity and care. And that, I think, is the invitation: to do those things that allow us to honor a currency of relationship rather than a currency of money. And so when I say, well, I don’t think we should scale them up, I really mean they probably wouldn’t work at a scale of five hundred to a thousand people, but they work really well at two hundred people.

And so, how do we, again, invest in our neighborhoods in our communities to create opportunities for things like tool sharing and community gardening and food sharing? And I think about the buy-nothing networks, for example, that are deeply community-based. Those are gift economies. And we get the benefits of, I suppose, the goods and services that come through those exchanges, but we also get the benefit of human relationships and mutual respect and the sense that you matter, that that network needs you and what you bring. And in a society where I think people are longing not only for community, but for purpose, oh, those are pretty good benefits.

EVI want to talk a little bit about the deeper spiritual values that are present in this book, and of course your work overall, and that your exploration of the gift economy seems to be pointing towards. There is this crisis of a lack of respect for the Earth as a spiritual being, one might say, and that we don’t value Her and all She brings because of the systems that have removed us, sometimes very, very violently. And your work is very much about inviting people to transform this and to want to change the bleak future that is now often being promised to us and to mend this relationship. So I wonder if you might speak a little bit about the deeper spiritual values that a gift economy could really lead us towards and help us learn to reembody.

RWKYeah. This is, of course, work that transcends human communities and the exchange of goods and services. What it means is that we are investing again in communities of care and compassion, not only for one another, but for the Earth. I think what we’re really leaning toward is a kind of interspecies justice, to say that this mutual responsibility that we have for one another is our primary spiritual responsibility. Not just pragmatic, but it is— I also love the term “practical reverence.”

EVOh, I like that.

RWKBecause this is deeply practical, but it has sacred dimensions, doesn’t it?

EVYeah.

RWKOf caring for one another and honoring the gifts that come to us. To me, the gift economy and our responsibilities to participate in it are very much tied to our spiritual responsibilities, which in teachings that have been shared with me, and that guide me, are those notions that in return for life in this beautiful, complicated place, we were given a gift to bring here. Each of us is to bring that gift. And to not give the gift is a betrayal of a kind of spiritual responsibility, a spiritual equation, in a way. And so gift economies offer an opportunity for individuals to say, here is the gift that I carry, and I’m going to share it with you to enliven our community, to enliven life around us. And that deep sense of purpose is a spiritual one as well.

EVYou know, to me the immense popularity in both Braiding Sweetgrass and “The Serviceberry” essay speaks to a deep-rooted hunger people have for this way of being rooted in reciprocity, for this sense of practical reverence, for being in caring, mutual relationship with all that’s alive around us, and that we are craving models and pathways into once again living in spiritual connection with the Earth. I wonder if you could speak a little to this hunger that is apparent—this innate desire that remains, although often buried in us—to be in conversation with this Earth.

RWKOh, yes. You know, one of the joys of the work that Braiding Sweetgrass in particular has done in the world is an almost daily flow of messages from readers who conveyed just what you’re talking about: of longing, of longing to be in right relationship with the Earth. And all the stories that are around us that divert us from that, to say, well, no, that doesn’t really matter. That’s not what being— That’s not what you’re here for. Braiding Sweetgrass has given permission, I think, to many of us to feel that longing. And the idea of being in right relationship with land—given the way that our species, particularly in this country and industrial economies, have inflicted so much harm on the marvelous creation around us—can also create this sense of shame and dishonor. You think: That’s not who I am. That’s not who I want to be.

And practical reverence offers almost a notion of redemption, to say: No, you are not just a taker, you are not a despoiler. You can be medicine, you can be medicine for the Earth. You can be a healer. You can participate in regenerative economies. You can participate in ecological restoration. You can contribute to justice within our own species, and interspecies justice. People are longing for a kind of permission to really be their authentic selves in right relationship to land. And I’ve been so gratified to see the ways in which people are taking this on, of feeling liberated to: Oh, I could be a giver. Well, here’s what I want to do. You know, somebody who said: I’m going to this education system that teaches us just to be consumers. I don’t want to participate in that. I’m starting a school, or I’m writing curriculum. Or the man who wrote me, who said: I’ve been in finance on Wall Street for most of my professional life, and now I can’t do it anymore; and I’m going to take my wealth and go create a regenerative farm. You know, there’s just so many stories of people feeling liberated to be in right relationship with the land, which for some reason they had just felt wasn’t even possible. And that’s the power of collective storytelling, isn’t it?

EVYeah.

RWKBecause when one person said: Here’s how I’m looking at this—it’s contagious and gives people agency and permission to take those steps so that we are not complicit in destruction. Because that complicity weighs on us, doesn’t it? It weighs on us heavily. And to be able to take those steps in a gift economy, in regenerative economies—to step outside of that complicity and resist it in any way—really gives a sense of power and agency and rightness.

EVYou offer a lovely example in the book of how intuitive and innate a gift economy is to us as humans. That gift-giving is a primal element of human relationships. And you point to the “maternal gift economy” here: the giving of milk from a mother to a baby, which really is “pure gift.” Mothers don’t sell their milk to their babies. The currency of this economy, this exchange, is the gratitude and love in support of continued life.

RWKIsn’t that a powerful idea? Genevieve Vaughan was the first to talk about this. And I’ve only scraped the surface of trying to understand the work that’s being done around maternal gift economies. I want to learn more. And I plant that as a seed for readers to learn more as well, to say, well, what would that look like to live in such a way that honored these exchanges of life? What those thinkers, those wonderful feminist thinkers, are arguing is that gift economies are a biological imperative. If we didn’t do this, we simply wouldn’t be. So how could that translate into means of social and economic organization based on blurring the boundary between me and we? That’s part of the beauty of the maternal gift economy: the boundary between mother and child is so porous, right? It really is an exemplar of this idea that all flourishing is mutual. Our lives are so linked, but truthfully, all of our lives are linked. And when we start to think about the ultimate mother from whose body we are fed—of Mother Earth—what does a maternal gift economy look like in that realm? It’s really exciting arenas of thought.

EVHand in hand with what’s shown by the maternal gift economy, you go on to suggest that like the sun is “the source of flow” in the economy of nature, perhaps the source that replenishes the flow of gifts in the human gift economy is love.

RWKIn the maternal gift economy, I think that there’s no argument about that, right?

EVNo.

RWKBut it’s a kind of, again, practical reverence of love and milk. We need both. Love alone is not going to nourish that infant. And it’s, again, when we think about the story of the hunter who says, I store my meat in the belly of my brother—isn’t that love, isn’t that love for your people? And there, the boundary between me and we is also blurred: that the gifts of the Earth, that hunted food, don’t just belong to me, they belong to all of us. And I can be an agent of distributing that abundance to the we. And I think all of this really leads us to that acknowledgment that we live in this society that is so hyper-individualistic that we think that all of the benefits are to accrue to individuals and their tight circles. Whereas what would it be to think about, as in an ecological system, where the benefits flow to the whole community?

EVRobin, it’s been an absolute privilege getting a chance to speak with you today. Thank you so much for joining us.

RWKThanks for a good conversation.