On Time, Mystery, and Kinship

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

Jane Hirshfield is a poet, essayist, and translator whose poetry collections include Given Sugar, Given Salt, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; After, which was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and named “best book of 2006” by The Washington Post and others; The Beauty, Ledger, and most recently, The Asking. Recognitions include Columbia University’s Translation Center Award, the Poetry Center Book Award, the California Book Award, and the Hall-Kenyon Prize in American Poetry, and fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller Foundations, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Academy of American Poets. In 2004, Jane was awarded the 70th Academy Fellowship for distinguished poetic achievement by The Academy of American Poets. And in 2019, she was elected into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In this conversation, poet Jane Hirshfield locates time as part of the great mystery of the cosmos, embracing its largeness and unknowableness from a place of humility. Reciting several of her poems, she shares how an inner spaciousness can draw us towards being in service to the Earth.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeJane, welcome to the show. It’s a pleasure to have you here.

Jane HirshfieldWell, thank you so much.

EVI wanted to begin our conversation today by talking about the poem “Time Thinks of Time” you wrote for our latest print edition. But I wonder if you might read it for us first.

JHOf course.

Time Thinks of Time

(And the poem begins with an epigraph from a much longer announcement put out by the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.)

“15 years of radio data reveals evidence of space-time murmur.”

Perhaps like a new planet,

you were only a state-change.

You didn’t exist, then did, inside all your colors,

inside your vertiginous unfolding no eyes were present to see,

no mind yet there to take in or imagine.

We may try to think of you, Time,

but you, Time, think yourself continually,

without need of imagination, assistance, or witness.

Think also us.

What might have been different,

could we interrupt you?

The pondered diamond

that would have been flawless, priced beyond measure,

turned instead to department store bauble.

Some biologically living world that doesn’t exist.

It could be you were interrupted when thinking of me—

your bus-station beloved,

your four-thousand-week or so stand.

But no. Time cannot be interrupted. It can only be bent.

Also cannot be kept,

despite that odd locution, time-keeper,

said of wristwatches, nightstand alarm clocks,

referees, prisoners—

You slipped inside your spinning nebulae

as if into the Siberian tiger I once found asleep in the San Diego Zoo,

and lay beside, a wall of one-way transparent plastic between us,

while you, Time, ate us both up.

Last year’s rose bush opening this year’s flowers:

one of your definitions.

Another: what keeps everything from happening at once.

I read in a book “thirty earth years,”

and glimpse,

for one earth instant, your non-earthly Face.

Your prosopopoeia is us.

By which I mean: all—galaxies,

deer flies, protons, matter bright, matter dark,

swarms, flocks, herds, dustings, sneezes,

virga existences gone before reaching ground,

the ultrasound’s shadowy heartbeat,

gone before reaching ground.

One hundred thousand years ago,

one of your shadows began to imagine you back.

Now, those who listen report

a new fingerprint to study the whorls of—

“the space-time equivalent of car horns, jackhammers,

shouts.” The dance club’s floor bouncing.

A vibration felt only in instruments’ low-strung ears.

Senses vulnerable, human, could not bear it.

Senses able to notice you

only at certain amplitudes, particular speeds.

For the rest,

your waves pass through us almost unnoticed.

Almost.

“A rumpling,” one article describes the new discovery.

Morning sheets after a night of love rise to mind.

One lover brushes her long, gray hair

while the other makes coffee,

waits for this instant’s kettle to come to this instant’s boil

by the grant of a minor, peripheral, not-yet-run-down star.

Six billion years or so of earth-mornings remain,

a stray neuron of memory reminds—

enough, for now.

Enough for these lovers to pass their lives in,

to talk about planting next year’s trial-garden roses,

better resistant—though not entirely—to rust, blight, early black spot.

EVIt’s a very beautiful poem. And I love the way it characterizes time as a presence with its own agency. And like many of your poems, it brings you into an almost visceral encounter with the wonder of the ordinary or the invisible. And as far as I understand, the poem grew in part from a scientific discovery you came across, in which scientists detected a cosmic background of ripples in the structure of space-time.

JHExactly so.

EVCould you talk about this discovery and what struck you about it that you go on to explore within the poem?

JHWell, first of all, what struck me is simply the astonishment that we now have instruments that can recognize such a thing and that we can still be completely surprised by the deep physics of existence—and that this is somehow connected to time, space-time murmur. You know, the very language of the scientific reporting was part of what caught me. You can’t hear so much when I read the poem. You could see it on the page, you know, the phrase about the—I’m trying to find it now. There’s a quote from the scientific report. Ah, yes. “The space-time equivalent of car horns, jackhammers, shouts.” That’s in quotations on the page. And I don’t think that’s NASA’s report that said that, but it was one of the scientific journalists trying to give us some sense of the quality of the sound. And that just absolutely struck me. And then from there, I had the immediate association myself to say, “the dance club’s floor bouncing.”

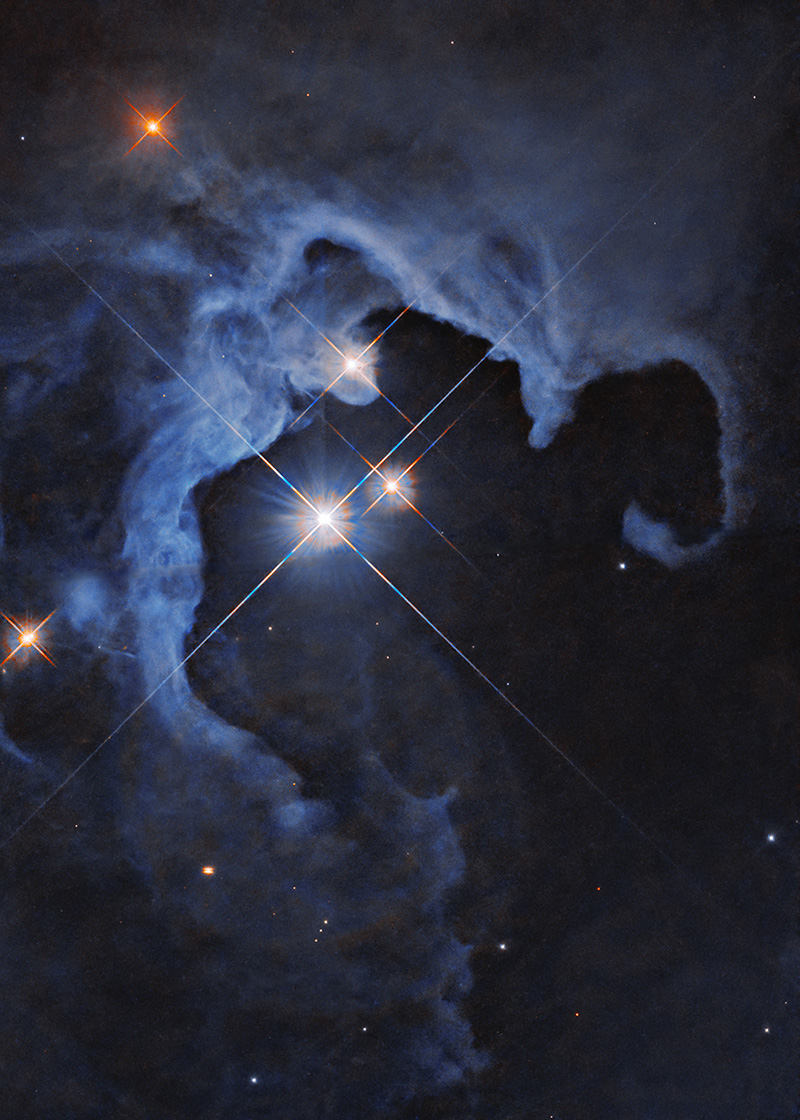

So that was what sort of alerted my antennae. I knew that I had been requested to write a poem about time, because this is how Emergence works. You know, it is the most—for anyone who has not seen it—it is the most extraordinarily beautiful publication. And I think this volume, you know, even transcends the previous ones, which are, each of them, original works of art in themselves as objects and embodiments of not only language, but what is possible with the printed page when brilliance and artistry and the respect for the physical object of words in ink reaches its pinnacle expression. So anyhow, sorry, a little praise of Emergence in there.

EVYou’re too kind.

JHBut I knew I was—my antennae, my own Hubble telescope of the poetic muse—was scanning for a way to enter this request to contribute to the special issue on Time. And so when this article came through, I just recognized it at once. Ah, there we have it. Now I don’t get into the article immediately, except that the epigraph refers to it, but I’m just kind of pondering time in, as you said, the grammar of time being someone you can talk to, time being personified. And I love poems in general. One never wants to do anything all the time, because that would be very boring. But I love poems that include the second person in them. There is a great intimacy to that. And time is, in a way, such an unimaginable invisible force in our lives that to speak to time directly allowed me to think in a different way, and a more intimate way, and a way in which the imagination, I hope, does not disrespect time’s imperviousness to us—which is what the beginning is pondering, you know, that time doesn’t need our imagination, assistance, or witness. And yet, we in our human lives, being mammals—singularly perhaps, or at least well on the one end of the spectrum, aware of the fact that we live within a span of time—we are constantly in conversation with it, even though it does not need us.

EVMm. Something I felt that was very present in the poem was an acknowledgment and maybe in some ways an honoring of the mystery of time. And part of what our recent exploration of time that you contributed to has been focusing on is the ways our modern culture has stripped time of its primordial sacred mystery as we’ve mechanized it and diluted it, and taken the magic out of it, and in many ways turned it into a form of control. But I’m very much of the belief that there remains a fundamental mystery to time that we can tune in to or return to, that in turn brings us into contact with something essential. And like the poem says, “We may try to think of you, Time, / but you, Time, think yourself continually, / without need of imagination, assistance, or witness.” And I felt like you’re feeling into time’s obscurity, its mystery as a force that we can’t quite truly know.

JHOh, absolutely. Its largeness. Its unknowability. Its untouchability—that, you know, time can’t be interrupted. I have in recent years come more and more to find absolutely indispensable—as a way to navigate this confusing world we are part of and to recalibrate my relationship to it—the idea, the feeling, of humility. And I think mystery and awe and the recognition that something is larger than we are and untouchable by us counters the arrogance of ego, of the industrial revolution, of the idea that we humans are somehow in control. And you know, there are very different kinds of spirituality in this world. And I don’t want to say that any is preferable to any other, but all of them have some acknowledgment of a little humility in them. A little acknowledgment that, no, we are not the all-powerful ones. And I think that is a corrective to so much that in the end brings upon us all, in private ways and in public ways, only an increase of suffering. I don’t want to take away my equal treasuring of the sense of human agency. We are not passive, we are not incapable of changing our own actions, thoughts, ways of relating to things, ways of understanding. But for me, there is this perennial reminder of how important it is not to think that I am ever in total control.

EVHmm.

JHIf I am, I’m just going to disappoint myself, no end anyhow. I will fail. We will all fail. Every single one of us is mortal.

EVThere’s a line from the poem: “I … glimpse, for one earth-instant, your non-earthly Face.”

JHYeah.

EVYou know, and that seems to speak to that larger other—which is not just outside of a human lens, but also an Earth-based lens—that opens us to the mystery and the mystical sense of time.

JHExactly. And as the line right before that says, “I read in a book” and then again in quotes this phrase “thirty earth years.” And that’s something the physicists know quite well: what a local unit of measurement an Earth year is; that even within our own solar system, every one of the planets has its own quite-different-in-length year. And I just loved how I suddenly realized, Oh, you know, time does not travel through the great expansive existence on Earth time; but Earth time is our time. And that’s why the poem ends with this intimate portrait of two lovers in the morning making coffee and planning the garden. I think, again, for me, in my own relationship to navigating this life and to my sense of mystery and the large—that is not to turn away from the radiant intimacies of what we have so astonishingly been given: sheets, coffee, roses, you know? How amazing is that? How lucky is that? What a life we get to witness for our brief time on Earth living by earthly years.

EVWell, I’m curious to go back in your own story a bit about your experience with Zen and how this impacted your relationship to time. Because in your twenties you spent, as I understand it, eight years living in a Zen monastery, which I imagine would impact how you relate to time and perceive time in many ways. So I’m curious about how this impacted your relationship to time.

JHYeah. Big, big question. So, just a slight factual correction: eight years in full-time residential practice in Zen communities, but only three of them were in the monastery.

EVOkay.

JHAnd that monastery was the first Buddhist monastery in existence in America: Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, inland from Big Sur. And I came to San Francisco Zen Center in a red Dodge van, with tie-dyed curtains and a built-in bed and wall-to-wall carpeting, in 1974 as a quite young woman, because I knew Tassajara existed, and because I knew that if I was going to investigate this practice of Zen that it was monastic practice that I was interested in. And living in the wilderness in that way— In those years, of course, it was long before solar panels, and Tassajara had, you know, a generator to run the kitchen so there were lights for the cooks who were making breakfast before daylight arrived. But the rest of the monastery was living by the natural world’s light and dark and weathers with only kerosene lamps. And we didn’t even have glass on the windows in those days. The windows in winter were covered with plastic. And in summer just screens. The cabins were, in those days, uninsulated wooden cabins. You couldn’t be closer to living with no human skin around your existence at all; except, you know, a tent would’ve been a little closer. Nothing would’ve been, you know, the true mammalian life.

But one night when I was there—forgive me, I’m free associating here—but one night there was an earthquake. And because I was sleeping in this little, almost non-existent wooden cabin, raised perhaps eight inches off the ground, I heard the Earth during that earthquake. I heard the actual—you know, maybe the rattling of the kerosene lanterns woke me up—but I heard the Earth itself. How rare that is for most of us in this modern world. And so, as a person who grew up urban—I grew up in Lower Manhattan, New York City—that, as quickly as my life allowed it, I ended up spending three years almost unmediated between time, the seasons, the Earth. In the summer when the creek was low, you’d hear mountain lions walking down the creek yelling at one another—I think in love, not in argument. And the stars are very visible at Tassajara. There’s something about the flow of the atmosphere right there which makes it one of the clearest places to see the stars. Now I’m talking about physical things rather than talking so directly about time, but time is part of all of those things: you know, day and night, summer and winter, fall, spring; creek high from winter rains, creek low from summer drought. This is how time enters our lives locally and by what, we who know existence by our human senses. You know, that’s what time actually means to us. Just as right now, as we tape this, so obviously the turn into autumn has come to where we each speak from.

So also, of course, in a monastery you don’t wear watches. You might have a little battery-operated alarm clock if you want to wake up before the wake-up bell. And I often did, because I will confess that every single day of my life in that monastery, I woke up a little early so that I could make myself a cup of coffee before zazen. The more proper monks were making themselves green tea. But I was making coffee with a little alcohol stove. And again, you know, the texture of time in our lives— I very quickly got— So an alcohol stove, you pour some liquid alcohol into a catch bowl, and then you put a match to it, and you put your water over it, and it’ll boil your water. And without any measuring instruments, I so quickly got so that I just knew—my hand knew, my body knew—exactly, to the drop, how much alcohol to pour into the stove for the water to come to a boil and then the fire go out. This is what time feels like in our lives.

And you didn’t wear a wristwatch. You began zazen with the bells that tell you it’s starting. The period ends with the bell telling you it ends. The period of several periods of morning zazen ends with a drum and a wooden instrument called a han—so, a wooden block hit with a wooden mallet. And that does roughly tell the time: you know, the hours and then whether it’s the first third of the hour, the second third of the hour, or the last third of the hour.

Sitting in meditation, time’s elasticity becomes very clear. Some periods of meditation are over in an instant, some of them last two and a half years. You know, so again, you understand how our sense of time is completely affected by how we meet time. Sometimes time can actually disappear. Sometimes time will return to you because the first bird of the morning begins to sing, and there is no separation between the singing and the ears that hear it and take it in.

EVHmm. You’ve also spoken about how your Zen practice taught you to pay attention.

JHOh yes.

EVSo I’m curious about specifically what kind of attention that is and how this influenced how you perceived time. But also another big question: how you write a poem?

JHWell, I’m glad you added the last, because it does seem to me that attention is kind of the entrance gate to anything and everything. You know, it’s the entrance gate to parenting. It’s the entrance gate to having a conversation with a horse, if you’re trying to decide whether this scary puddle can be crossed or not. It’s the entrance gate to playing a musical instrument. Nothing in this world can be done well if you’re not paying attention. If you’re distracted, if you haven’t learned how to bring yourself in an immediate and wholehearted way into whatever it is you are doing, in a way, you don’t have your life; your life slips away from you like water you’re trying to hold in your hands. It is your attention that tells you to cup your fingers in a way that the water will stay in your hands long enough to lower your mouth and drink from them.

So, Zen practice is in a way almost entirely about attention, and particularly at Tassajara and in the San Francisco Zen Center lineage, which began with the teacher Suzuki Roshi but goes back to the Japanese thirteenth-century teacher Dōgen, who brought Chan from China to Japan in this particular form. This is not the Zen of doing koan practice, where you are working with verbal riddles that are deeper than riddle. The practice of Sōtō Zen is shikantaza, just sitting, just being attentive. And as anyone who’s ever taken up meditation or tried to take up meditation knows, our minds love to wander. They love to talk to us. They love to skip around. They love to rehearse the past or rehearse the future, run scenarios. They’re skittish little colts, our minds. And meditation practice is a way to notice the skittishness and call the colt home and say, Ah, try this, try this, try this. Come back. Here’s a bucket of grain. And the grain, of course, is the great reward of stepping fully into a state of awareness in which the distractions of our ego’s lovely narratives can for a moment be stepped outside of. And then your relationship to the rest of existence becomes one of connection rather than one of sitting inside the individual room of your individual life all the time. It is as great a relief as stepping out of a house you’ve been kept inside of too long and breathing a larger air.

So I write poems— The instrument of writing is attention. I listen for a different voice to bring the words to me. And when I revise a poem, I revise it by reading whatever I have set down on the page in that first draft and feeling the effect of those words in me; feeling whether they have taken a wrong turn; feeling whether, okay, I knew what I meant, but that’s pretty obscure; feeling with my attention whether I find what I’ve written embarrassing, and then if I do, is it embarrassing in the way that tells you you’ve made a misstep—which is, Oh Lord, that’s cliched and sentimental—or is it embarrassing in the way that says, Oh, I’ve exposed something here, do I feel safe exposing it? And that one you want to really think about allowing to stay in, not taking it out, not calling it an error. That’s the kind of courage it takes: to be—not only to expose your deepest inner ponderings of this life and your experience of it, but also the simple courage it takes—I think, being built the way I am—to be seen at all.

As a child, I hid in my room and read most of the time. I didn’t really want to be looked at. I was not an exhibitionist. I was the opposite. I was, you know— Animals have different strategies of safety, and some of them go parade out in the world and look very big and fierce. And some of them blend into a pebble or, you know, a stick: a stick insect that looks like just another part of the branch. That was my nature. And one of the things that quite surprises me in this lifetime is, how on earth did such a young person ever turn into a person who talks to strangers in public as much as I do?

EVThere is a timelessness when one is truly in the present in a space of pure awareness, as you just spoke about, in part, and that this space can, as the mystics often say, open the gates to mystery.

JHYes.

EVAnd I feel that in much of your poetry, throughout your work, and you’ve said that the writing of poems allows the mystery of existence to slip the leash we so often try to put on it. And I like that very much. And I wonder if you could speak to this a little bit, about this slipping the leash.

JHYeah. What a lovely phrase. I never remember a thing I’ve said or written—my lifelong terrible memory—but I hear that and I go, yeah, that sounds like me. So, you know, what is the leash? The leash is in some way— You know, I have great compassion for how difficult it is, even for the great mystics, to continually dwell in that place of openness. Many, many years ago, I put together an anthology called Women in Praise of the Sacred: 43 Centuries of Spiritual Poetry by Women. And I did it because someone should have done it ten years before. You know, there had been a great wave of feminist research telling us, showing us, that Virginia Woolf’s image of, there were never any women writers before us— It’s accurate in one way, but in another way it was—forgive me, Virginia, great soul, great writer, pantheon figure for me—ignorant. Because anywhere that human beings do anything, be it spiritual practice or writing a poem or inventing writing itself, women will have been part of that; it’s just that many cultures suppress the evidence of it.

And so, studying the lives of all of these women from all over the world, in every tradition that I could find, what I found was something I had not known until then, which is that even after the greatest openings, people still have dark nights of the soul.

EVYeah.

JHAnd that is in some way comforting to all of us who feel like, why aren’t I walking in total openness to the mystery all of the time? When you see that every single great mystic—you know, St. John the Divine, Hildegard of Bingen, Mirabai—every tradition, the dark nights of the soul come after the great experience of opening as well as before it. And this is because the leash is strong. And I have a theory. I can’t justify the theory, you know, I’m a poet, not a scientist. And I doubt that even scientists will ever quite be able to say, oh yeah, that’s right, or that’s wrong. But I think that one reason it is so difficult for human beings to step outside ego and fear and self-concern is because evolution built us to be self-concerned. If you want to survive the dangerous world where you might be eaten by a tiger, maybe it’s a good idea to have some sense of self-protection. And so in a way, the great mystics are transcending evolution itself and how much our brains and bodies have been attuned to survival, just pure survival—not wanting to be hungry, not wanting to be the one who is eaten. That’s evolution. And so slipping the leash is recognizing that in many, many circumstances we can set that down.

I think, to go to a different explanation system yet, I have always loved the psychologist Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, in which he says: First, people need safety, shelter, food. And then there is this pyramid of, what do you need before you will be able to feel free to engage in art, to feel free to engage in generosity, to feel free to not put your own self-preservation as the glasses you look at the world through. And so the great mystics—the truly great mystics—they are able to do this even when they are cold, hungry, and in peril. And maybe that’s one of the things that meditation or prayer or long abiding, in the sense of the divine or the large—whatever language one wants to put onto this experience—it shows you that you are always safe and the world is always abundant if your own next meal is not the most important thing.

EVCan I ask you to read your poem from Ledger, “A Bucket Forgets Water”?

JHYes.

A Bucket Forgets Its Water

A bucket forgets its water,

its milk, its paint.

Washed out, re-used, it can be washed again.

I admire the amnesia of buckets.

How they are forthright and infinite inside it,

simple of purpose,

how their single seam is as thin of rib as a donkey’s.

A bucket upside down

is almost as useful as upright—

step stool, tool shelf, drum stand, small table for lunch.

A bucket receives and returns all it is given,

holds no grudges, fears,

or regret.

A bucket striking the mop sink rings clearest when empty.

But not one can bray.

EVMm. I loved this poem and the collection that it’s part of, and specifically the way you speak to emptiness here in sometimes a utilitarian manner almost. But also, like, the bigger question I guess is, within your Zen practice, emptiness has played a central role, and that comes through your work. And there is this experience—whether it’s fleeting or not—within emptiness, that also opens us to mystery, that is a gateway that helps us slip the leash.

JHYes.

EVCould you talk a little bit about that and how you work with emptiness, maybe in your writing, but also in the way you live your life?

JHYeah. So, you know, “emptiness” is a translation of a Sanskrit word that entered English early and stayed. But many people who have actually, you know, explored that word and its original meanings and usage, they say that it might have been better if we had chosen “spaciousness”—which confuses in another way. You know, this is the thing: language points to experience, which those who have had the experience know exactly what’s meant, but those who haven’t can be misled by a word’s other associations.

And I wanted to open by saying that, because I know for people who have never practiced any of these Eastern religions, “emptiness” can imply nihilism. And it is not that. It is much more, as you say, the state of unboundaried participation with the mystery. And it has to do, I think particularly in this poem— What the poem is exploring—and you are quite right that it is a poem that has Zen practice deep in its bone marrow and DNA—is the setting aside of fixed identity and fixed label. And that when the bucket isn’t a milk bucket or a paint bucket, or even a bucket at all when it’s turned upside down and it’s a table for lunch, look how much more is possible when the bucket doesn’t cling to “I have only one job in this world. I have only one definition in this world.” And so you get, eventually, to the, you know, you can’t hold grudges or fears or regret if you are not fixed in one story.

And then, the penultimate line: “A bucket striking the mop sink rings clearest when empty.” And I think for me, again—you know, all I can say is my own experience, which is the experience that came within a tradition. But when— I like to say, to put it a different way than I was about to, the peak experiences of my life have all happened when I wasn’t there. You know, I wasn’t Jane. And for me, those experiences of really feeling the entire unboundaried fabric of existence, which—like those time ripples of the first poem—it does express itself in details, in substances, in a bird singing or a creek flowing, or the person next to you coughing. But when you are not separate from those things—oh, this feels to me like the truth of the matter. The truth of the matter. And the rest is a different truth. And it is to be enjoyed, and it is to be cared for.

You know, in Zen you take care of every object you touch. You hold a bowl with both hands, you set it down softly, with tenderness, compassion. Sometimes this is described as if it were the baby Buddha. You know, that’s a helpful mnemonic. But if you spend years, and everything you touch, your intention is to touch it with the sense that it is not separate or outside some shared life, then emptiness, spaciousness, begins to be your, never constant but perhaps more frequent, companion. And I think it changes people.

And I think, you know, one of the things many of my poems do, and I don’t know that we’re going to have an example of this in any of the poems we read, but often I write poems to find something or rediscover something for myself. Poems are a— Always, I’m trying to change my relationship to wherever I was before the poem, to something different after the poem. One can say that, you know, any period of sitting zazen for forty minutes has the same intention: that you walk in one person and you walk out a slightly different other person. But one of the things that I am often looking for in my poems is a way to address my perplexity at what this world seems to be like. And so, you know, years and years ago, way back in 2004, I wrote a poem called “Global Warming.” And what it was actually—yes, it was looking at the fact that there is global warming—but what the body of the poem— I can read it to you if you like. It’s very short.

EVPlease, please.

JHIt’s only like four lines. So I probably have it by heart, but I’m going to find it in the book that I have, because then I won’t be nervous about getting a word wrong. What I was perplexed by was, how can anyone who has children or grandchildren or imagines the future, how can anyone not behave—2004, remember?—as if global warming is established fact, and as if we might need to do something to prevent its getting worse? And so I’ll read you the poem and then I’ll say why this introduction led to this poem.

Global Warming

When his ship first came to Australia,

Cook wrote, the natives

continued fishing, without looking up.

Unable, it seemed, to fear what was too large to be comprehended.

Now that’s a true story, and I found it in the historian Robert Hughes book about Australia. But why this poem led to this title and this framing—why that story led to this—is it helped me find compassion for the climate deniers. And I want to find compassion. I do not want to be angry, and I do not want to be totally bewildered, which is how I was feeling, and say, How can anyone—said the indignant, leaping little Jane inside of me, How, how, how? And when I found this story, I understood how: “unable to fear what was too large to be comprehended.” And, you know, right or wrong, I’m sure there were some people who understood just fine and decided to be short-term greedy over long-term concerned. But I feel better as a human being if I can find compassion. That was a long detour. You can bring us back to wherever you wanted us to be now.

EVIt was a great detour. And I did want to speak about kinship, both as a kind of a segue from “emptiness,” because I feel like— Or “spaciousness,” which I love as a term, to expand, as I agree that “emptiness” can be confusing.

JHYes.

EVAnd spaciousness is the space you were taken into through emptiness.

JHYes.

EVI wanted to speak about kinship, because in those spaciousness encounters that we have, we are brought into relationship with the more-than-human in a way that can be quite impactful and change so much—especially in light of kind of understanding what is too enormous to understand, because climate change can be overwhelming unless you feel it. And kinship can be a gateway to feeling.

JHYes.

EVAnd moving a scientific fact into a felt experience in the body that one has to take responsibility for.

JHYou have just named why poems matter in this conversation. That’s what they do. Finish your sentence, please.

EVAnd I’ve been repeatedly touched by how you work with kinship, and it feels like a very big theme.

JHYes.

EVAnd you know, I guess my question is that the power of the poem not only to open us to kinship, but there’s a magic—at least I believe there’s a magic in poems and in all good forms of storytelling—that has the capacity to hold a connection between that which you have kinship with. Like a poem or a story can weave something together, can help weave a bridge between the worlds that have been severed, create those ties of kinship. They don’t just open us, but they actually hold a little magic. And I’m curious to hear your thoughts about this.

JHWell, first, I have been—if people could see me—I’ve just been nodding and nodding and nodding at what you have said. And here’s another shorter detour: I once was asked to do an onstage conversation with Barry Lopez, and it was on this realm of, you know, the spiritual, the large. And the place that had asked us to give it gave us a title that neither Barry nor I liked at all. And Barry and I then had a forty-five-minute conversation—because we do come from different quadrants of experience—about what word we could both feel served the subject. And the word we landed on after forty-five minutes was the word “numinous.” The numinous. And afterwards I looked up its etymology—because I like to do that—and the word “numinous” comes—its taproot meaning—comes from the word meaning “to nod,” to say yes physically with your body.

So kinship— I think there is a continuum between the ideas of kinship, which has to do, you know, again, etymologically with the sense of family, the sense that we are connected, that we have ties. It also is very close to the word for kindness: “kinship” and ‘kindness” are related. Your “kind” is also those who you are among, who you live your life among. And then the idea of kinship in poetry or stories, I think what that connects to then is this line that runs through kinship into imagination, which is the house in which all creative art is made. And then the idea of empathy, of compassion and empathy. And I sometimes feel—this is almost impossible to say because it’s such a felt sense of the world—but I feel like everything is empathy. Anything that you learn or know or take in from beyond who and what you already are, you know that because you experience it inside your body; you take in a fact or an image or a novel that you are reading, and you feel it from the inside.

So, you know, the neuroscientists have discovered that if you are reading a book and in it there is a mention of eating an orange, the same part of the brain that lights up a little when you yourself are actually eating an orange, it lights up. So we feel everything from the inside. The only instrument we have to play the music of existence is our own interior felt embodiment of this world, and what we ourselves have known of it, have taken in from it. And so, you know, kinship, imagination, empathy—for me these are all words that have to do with connection. They’re all words that have to do with, you know, we can call it “emptiness” or “spaciousness,” we can call it “nonduality.” But this sense of: I am a thread in an endless fabric. I am not a cut-off isolated phenomenon. And I just feel better when that sense of the full fabric of existence, going backwards in time and forwards in time and outward in every direction, accompanies, you know, this small boat that I am rowing through this world.

EVThere is something that you said about kinship that I came across while preparing for our conversation that I really loved. And it speaks to the compassion and empathy that you just mentioned. And you said, “If we are aware that we are born into this world in a space of inseparable kinship, it gives us a little bit more tenderness to our own failures, our failures of separation.” And I found this very moving, and also deeply practical, on the other hand, as so many of us struggle with the complicity we feel in relation to the climate crisis—that we’re constantly failing to respond.

JHYeah. Well, there was that marvelous thing that Václav Havel once said, which was, You don’t do the right thing, or you don’t do good, because you think you’re going to win. You do it because it is the right thing, because it is good. We may fail. And that idea has been in my poems from, you know, things I wrote forty years ago. There’s an early, early poem that talks about the world as a net of blue and gold—and a little bit that’s, you know, remembering Indra’s net from Buddhism, but also an experience you can have any day—and it ends with, How is it we fail so often in such ordinary ways in the face of the continual presentation of miracles and radiance and awe? And I think one must be tender because despair does not serve us. And falling into only self-castigation— You know, you need a moment of the pure discomfort that says, Oh, I’ve made a mistake. You know, that’s really useful information. We all make mistakes, and we should know when we do. And that sharp, sharp emotional pang of shame or self anger—you feel it, and then you respond to it. And the response can be: How can I repair this? What do I do differently in the future? How do I speak differently? How do I act differently? How do I go to that person whose feelings I’ve hurt and show them some tenderness and show them that I care about their future, and not only my own—and their present, and not only my own.

So climate change, you know— We may fail. We may. The evidence is not looking good. But any remedy matters. Any small act. The fire protection agency where I live just made me take a tree down, because if there were a fire, it would burn explosively. It just hurt my heart. I said, how can we in this— The reason that the fires have increased is in part that we have deforested the world. And you think the answer is for me to take another tree out of this world? And so, you know, I did it. They said I had to do it. But cutting down that juniper tree, I felt like a murderess. And I felt like, this can’t be. I don’t know what the solution is— Well, you know, we do. We know how houses can be built less flammably. But, for the moment, what they’re concerned about is that I not contribute to my whole community, you know, succumbing to a big fire. And I can understand that as well. We live amidst these colliding currents of knowledge and action and somehow must treat ourselves tenderly, because we will do what we can.

So that was a recent and difficult dilemma for me, and it’s one tiny example of all of the choices we have to make as we live now. I have a kind of signature poem for many people—again, from years and years ago—that talks about how there’s a second-growth redwood tree quite close to my house, and they won’t make me cut that down because redwoods are protected. But someday, as that tree gets larger and larger and larger, it and the house are going to have a little dispute about, you know, whose space is this? And in my poem, I vote for the tree. You know, it was here first. When I compare the life of an eventually thousand- or two-thousand-year-old tree to a room, who deserves to continue their existence? And who contributes more to the well-being of how many beings? How many creatures must live in that tree—that’s their house.

EVYou spoke about despair, and there’s something that you said about despair as a response to it that I think is very potent. That it’s simply rude, it’s simply rude to despair at the state of our moment without acknowledging the beauty and wonder that continues to unceasingly color our existence on this Earth. And there’s a duality that’s very present, as you were just speaking about, in our moment of ecological unraveling, in which loss and beauty are almost two sides of the same coin. And you get at this idea very powerfully with the image of “kerosene beauty” that you evoke in your renowned poem “Let Them Not Say.” Could you read that for us, Jane?

JHYes, I will. And yeah, before I do, I will just say, I took up a practice and I think it is a practice against despair. When I went and did a festival in Australia not too many years ago, but pre-Covid, I heard a phrase, a saying; something Australians, as an expression of happiness, say: You beauty, you beauty. And I took up the practice of, every morning when I first wake up, whatever I open my eyes to, which when I’m home is Mount Tamalpais out the window, but whatever it is, you know—even in some hotel room in Kent, Ohio, which I just came back from—I open my eyes and I try to remember to say to the world, whatever it is, You beauty. Because, yeah, that’s what keeps us going. Okay, here’s the poem.

Let Them Not Say

Let them not say: we did not see it.

We saw.

Let them not say: we did not hear it.

We heard.

Let them not say: they did not taste it.

We ate, we trembled.

Let them not say: it was not spoken, not written.

We spoke,

we witnessed with voices and hands.

Let them not say: they did nothing.

We did not-enough.

Let them say, as they must say something:

A kerosene beauty.

It burned.

Let them say we warmed ourselves by it,

read by its light, praised,

and it burned.

EVFor me, one of the things this poem evokes is the need to love the Earth.

JHYes.

EVIt will not be despair that saves it, or facts and figures at the end of the day. And we will not save all that is being lost or change our relationship with the Earth because it’s a good idea either.

JHHmm. Yes.

EVYou know, we’ll only reengage with the Earth as She really is if we love Her.

JHExactly. It’s something I say frequently. We will only work to save what we love. That is what we work to save. That is why, you know, the parent runs back into the burning house for the child, or why, in this sense of deep kinship and sympathy and empathy for the terror of it, a firefighter will run into a house and rescue a kitten or a dog. Because we love, because we know how it feels to love. And that is what we want to save.

EVTo me, love and intimacy go hand in hand, and there is an intimacy with the living world that is just a thread that runs through so much of your work. And as you said, goes back a long, long time. And this is something we’ve really been exploring at Emergence of late, how to dissolve the boundaries we’ve placed between the self and the living world through story.

JHYes.

EVParticularly in modern Western culture. And I’ve heard you use an example many times that works to kind of throw in relief the difficulty in enforcing such boundaries when you really stop to examine them. It’s a kind of cheeky example: you ask the question, when you eat a sandwich, when does it stop being a sandwich and start being Jane? And I love this because it’s so simple. You could share it to a three- or four-year-old, and they could almost grasp what you’re sharing here. And yet it’s incredibly profound.

JHWell, it is a question that I have asked since childhood, you know, and it came back and got into a poem, and that got me saying it more. But yeah, children are very metaphysical, you know.

EVLess boundaries.

JHThey want to understand. Yeah.

EVAnd this gets to that, because the firmness of separation that we like to place between our own bodies and the rest of the world is a huge obstacle…

JHYeah.

EV…to this level of intimacy, which, you know, is both a foretaste to the love we need to experience and then a deepening that comes from that love.

JHYes. Yes.

EVCould you speak to that a little bit? I mean, it seems something that you’ve thought about a lot in your work.

JHWell, I think that, again, all of these explorations that we do so often through words—because words are how we try to comprehend, although sometimes it happens outside words, and then I can’t talk about it because it’s outside words—but this remembering of the pure, simple, beloved facts of existence: every breath I take, the outside is coming into me, being transformed, and I am returning it to what is outside. And if you can actually feel your life in this intimate, simple, physical way, as not a barricaded place but a privilege of witness, then our intimacy with everything is felt. It is both cognitively undeniable that we are membranes. And the poem that that sandwich image shows up near the end of is a poem titled “My Proteins.” And it started out from a science article talking about scientists having figured out how itch works. And the answer is a protein called natriuretic polypeptide B. But the poem moved on then to what was then an equally recent addition to lay people’s understanding of ourselves in the world: the microbiome. And what the microbiome is— You know, who we think of as ourselves is actually ten billion independent organisms that live in our body and do that same transforming work that I spoke of us doing when we breathe in and we breathe out. And the condition of your microbiome—it affects your mood, it affects your intelligence. It probably affects your courage. And, you know, is that me or not me? And the more that I can feel it as not me, the more I can love the entire phenomenon in a way that feels kin, that feels spacious, that feels unboundaried.

There’s a whole series of my poems that, you know, the bucket poem is one of, “My Proteins” is one of—and they’re all sort of asking what in Zen is sometimes a question people are told to work with: Who is this? Who is thinking? Who is this moment? And you ask the question to dissolve it, to dissolve this sense that there is a separate who. If you look with enough attention, in enough safety—in enough sense of, okay, for this few minutes nothing bad is going to happen and I can lower the barricades of self-protection, I am safe on this meditation cushion—then the separation— You know, it’s like, we’re not separate. And sometimes we can feel things that way.

I’ve often, you know, tried— So like everybody else, I can fall into the grip of excruciating emotions. We are social mammals, and excruciating emotions are in us for evolutionary reasons, which is, if you’re ostracized by the herd, you’re probably in trouble. We need one another to live with. But sometimes— And I always know, at least, Oh, everything changes. This will also. If I wait long enough, I’m going to be perturbed by something else. Some new thing will bump this one out of the center of the field. But meanwhile, if you’re trying to say, okay, I have learned this, I take it in, I know what I can do differently from it, I am set on reparations or I am set on, you know, comprehension—

Sometimes if I want to quicken the escape process a little bit, I’ll simply imagine: Now, Jane, if you were a bit of calcium in your elbow, how would this moment feel to you? And you know, just sort of shifting what do you identify with? And sometimes it helps, because after all my elbow is not experiencing excruciating social emotions. It’s just busy, you know, being an elbow.

Your skeleton— There’s a poem right next to “My Proteins” in the book that those poems are in. And the poem right next to “My Proteins” is “My Skeleton,” in which I am also sort of going, well, you know, Is it me? Is it not me? You know, when I, the story of Jane, have died, the skeleton’s still going to be itself for a while, you know. And who is this? And what is our relationship? And what does it tell me? And that poem ends with a tenderness towards, you know— I’m talking to my skeleton and I say, “I who held you all my life / in my hands / and thought they were empty?” No, it’s like a mother holding a newborn child. Our relationship to the self and the not self—how do we feel that? And what happens if we can move our feeling more towards the whole and less towards the narrowest possible story of the desperate and injured and grieving ego—which has its own information to bring, but it’s not the whole story. And all my poems are looking for the larger story, because I feel better when I find it.

EVYou’ve talked about how the experiences of the self dissolving can recalibrate your heart.

JHYeah.

EVBut you’ve also spoken about how this leads to recalibrating your ethics.

JHHmm. Yes.

EVAnd I think that’s important, because sometimes there is this tendency to romanticize the mystical from afar.

JHYes.

EVThat it doesn’t have real practical ramifications. And you don’t, you know, fade off into a cloud of unknowing. Well maybe you do, but—

JHMomentarily, momentarily.

EVMomentarily. But then you’re in this world and you bring that experience back with you…

JHYes.

EV…and that has to have an ethics to it. And I don’t think that ethics is only relevant to those who might have had an experience of selflessness. I feel like it’s an ethics that we need to look at, because it is a holistic ethics in relation to our responsibility because of our kinship and where we are in the planet right now.

JHExactly right. Exactly right. Again, you know, what are religions or spiritual traditions but the recorded codification of what certain experiences leave traces of in us. And you know, I don’t think there’s any such tradition in the world that doesn’t speak of ethics, and doesn’t speak of—you know, in Buddhism, you have all those, you know, “right speech,” “right action,” “right understanding,” “right perception,” “right wisdom.” These are ethical. They are not just metaphysical. They have to do with: we are acting beings in a great symphony of existence, and what we do, however minuscule a difference it makes, it does make a difference.

And I love that you have brought the term “ethics” into the room with the idea of poems, because it is one of the things that I teach, and not everybody does. You know, not all poets talk about the ethics of poetry, but I feel it, and I feel that these things, they actually support one another. So if a poem has an ethical lapse in it, it also will not be as great art as it would be if it didn’t have that ethical lapse in it. There can be great poems that have bad moments in them. You know, we could go off on that detour, but I’d rather not. I myself choose to not lose the great poem or the great artist because they have made some error along the way in all they have written. You know, it’s like, I just— It is something— Where did I first hear this? You know, take the good and leave the rest. Praise the good and ignore the errors, and the child who you are raising, if you just keep praising the good, they will move towards it, out of love, out of feeling that, ah, this feels better.

But yes, you know, the ethics of poetry, sometimes it’s as simple as, don’t speak for something or someone who you have no right to speak for. So I tell my students, if they’re struggling with something like, they’d like to say that, you know, the deer is afraid that her lost fawn won’t come home. And we don’t actually know the interior life of deer. We can empathize, we can think we know what we’re seeing, and we’re probably not wrong—because I do think that we are continuous with all the other beings. But ethically in a poem, I say, you could say that better and not be accused of anthropomorphization or arrogance if you put it as a question; if you just say, is the deer afraid her fawn will not return? That’s ethical. You could do that.

But we shouldn’t probably pretend to know experiences that we don’t know. So if I write a poem that touches on some of the great catastrophes of the world, which I have done a little bit through every single one of my books. There’s not a book, going all the way back, that doesn’t have some poem in response to some war or conflict zone or catastrophe, because the world is never without such things. But if I know it only through the newspaper, I say that I know it only through the newspaper. That is my ethics in poetry.

And yelling at people is kind of unethical. I don’t like poems that badger. You know, badgering never won anybody over anyhow. But maybe that’s more an aesthetic error than an ethical error. I don’t know. A little bit of both.

EVI want to return to the theme of love and intimacy. And I came across something you said about the fact that no matter how many poems about love and mourning have been written, there will always be more poems about love and mourning. And this somehow reminded me of the endless poems about longing written by mystics—especially the Sufi mystics, or the endless poems trying to describe the experience of divine love, or union, or samadhi, or satori in Zen, it’s present across all the mystical traditions—who say that the experience can never really be described but then, of course, devote countless volumes to trying to describe it. And perhaps it’s because as essential or universal as mystical experiences can be, they are also deeply personal and deeply unique, and an expression of that uniqueness.

JHOh, yes, of course. And, you know, I do think— So most traditions have a set of poems—you know, the Song of Songs, or Mirabai’s poems to what Robert Bly translated as “the Dark One.” These are— They seem to be using the language of human eros as a metaphor for the longing for the Divine. And I have come myself to think of it more as, no, these experiences are a continuity, and that we learn the overpowering sense of longing or of surrender or of intimate joining; we learn that it is the same chords played on the same piano in different locations. But it’s not that one is a metaphor for the other. It is that one is— Each is continuous with the other, which is why I myself happen to love the spiritual traditions that don’t demand celibacy. You know? I think it just makes it a little harder, you know? Yes, yes, family and connection are distracting. And, you know, I understand why the— In theory, you know, the person who has—in Buddhism they call it “home leaving,” and they do part of the vows of ordination, even in Japanese Zen, where priests are allowed to marry. Part of the ritual is, you are leaving your family behind and taking that allegiance and love and dedication and widening it out to beyond your own home’s walls. So I do understand that. But I also think, these are not separate expressions of possibility. Both of them ask you to step outside your own skin.

So maybe that wasn’t what you were looking for, but that’s my feeling about it: that, you know, all longing is longing, whether it is longing for your beloved to come home or for your sense of union with the Divine, which has abandoned you, to return. Or, you know, in my case, because I’m not one of those poets who writes every single day: there are times when I write, and there are times when I don’t write. And when the times that I don’t write go on for too long, I begin to long for poems. I think it is all the same longing.

EVHmm. There was something you said about your own Zen tradition’s relationship to longing that intrigued me. You’ve said it holds it lightly, which is quite the opposite from my own Sufi tradition’s approach, which is more like grabbing it firmly with both hands and not letting go.

JHYeah. Yeah.

EVHow does one hold longing lightly? And how has this influenced your writing?

JHWell, first of all, let’s not— I never pretend to be a good Zen person or poet. I am me. And I’m not trying to live a doctrinal life. I’m trying to observe and participate and engage with this, you know, this point of view and body and story that I am inside of, which is deeply informed by Zen training but is not doctrinal. So, just to go back to what is meant in Zen by a statement like that: Zen meditation speaks of, when thoughts arise or emotions arise, or a story arises when you’re on the zafu, you don’t slam the door against it, but you let it pass through you the way the reflection of passing clouds fills a lake and goes. That is the lightness. It is the lightness of non-attachment, non-clinging, to anything, including— You know, one of the precepts you take in lay ordination, as well as priest ordination in Zen—and I am lay ordained—is, you know, a disciple of the Buddha does not possess anything, not even the truth. You just don’t hold anything with a tight grip. Because one of the teachings in Zen that is so forward is the acknowledgment of transience, the acknowledgment that everything changes.

And, you know, I love the Sufi poets. We all love the Sufi poets. And as a young woman, I did my share of reading, but I don’t claim to have a felt interior sense of what that fabric is like to live inside of when it comes to the emotions. There’s also an idea in Buddhism that at a certain point, if you practice in a certain way—or perhaps you’re just born into this world in a certain way—it’s described as (weird word) a “stream winner.” And a stream winner is someone who, lifetime after lifetime, they’re just gonna keep practicing. They might never, you know, there is no— In Sōtō Zen, you know, we don’t tend to fasten upon the idea of you’re ever going to be totally awakened and permanent and that makes you a special person or a special being. There is just this idea of, yeah, you know, the compass of my existence points to this particular north, and it is the north of certain kinds of understanding, certain kinds of how you spend your day. A feeling of, you know— In Mahāyāna Buddhism, which Zen is one part of, there is the feeling of service, that you’re not in it just for your own awakening. You’re in it— You will stay in this world of suffering until every last blade of grass is ready not to suffer. So that sense of, you know, change and non-clinging and non-attachment, I think, is what I must have meant when I said that.

EVI wonder if you could read one more poem to end our conversation today. And it’s about love and longing, but it’s also about time. A poem from Ledger, and it’s called “Ghazal for the End of Time.”

JHI have never heard that described as a love poem before. Marvelous. Yeah.

EVWell, for me it was.

JHYeah, I’m going to think about that quietly at home, because for me, it was a poem— The whole book Ledger is filled with poems looking at what I call the crisis of the biosphere, because it is climate change, but it is also toxins and extinction and habitat loss, you know, all of the many kinds of peril that the biosphere is in. And I not infrequently describe this poem as the darkest poem I’ve ever written. It scared me, this poem.

EVMaybe that’s the Sufi in me being drawn to the dark side of love, but—

JHAh, well, all right. I want to hear about this after I’ve read it, but first I’ll read it. So, just for people who may not know, a ghazal—which I am probably not pronouncing correctly—is a Persian poetic form, which this is only a very loose embodiment of: long-lined couplets, in which, if it’s done strictly, the same word will end, will be the recurring rhyme word. And in this poem, you know, I start with “open,” but then it moves through other words as well, which sound—more or less, they make the same music as the word “open.” So that’s what a ghazal is.

And the title of it, “Ghazal for the End of Time,” comes from a piece of music written in a German prisoner-of-war camp by the French composer Messiaen. He wrote Quartet for the End of Time. And he described that quartet as only a celebration of the greatness of God. And I hear that quartet as grief and mourning and sorrow. So I hear a great deal more darkness in it than he described. But mostly I took his title, you know, “for the end of time.”

Ghazal for the End of Time

Break anything—a window, a piecrust, a glacier—it will break open.

A voice cannot speak, cannot sing, without lips, teeth, lamina propria coming open.

Some breakage can barely be named, hardly be spoken.

Rains stopped, roof said. Fires, forests, cities, cellars peeled open.

Tears stopped, eyes said. An unhearable music fell instead from them.

A clarinet stripped of its breathing, the cello abandoned.

The violin grieving, a hand too long empty held open.

The imperial piano, its 89th, 90th, 91st strings unsummoned, unwoken.

Watching, listening, was like that: the low, wordless humming of being unwoven.

Fish vanished. Bees vanished. Bats whitened. Arctic ice opened.

Hands wanted more time, hands thought we had time. Spending time’s rivers,

its meadows, its mountains, its instruments tuning their silence, its deep mantle broken.

Earth stumbled within and outside us.

Orca, thistle, kestrel withheld their instruction.

Rock said, Burning Ones, pry your own blindness open.

Death said, Now I too am orphan.

So maybe you can talk about the poem a little first and tell me what you heard in it.

EVWell, to me, I feel the opening that the grief brings to us—and I feel that grief in the poem—it is a form of love being thrown in our face in a very direct way. The grief of what we have done. And, again, maybe it’s the Sufi in me, this pain of separation that the dark night of the soul can take you towards, deeper and deeper, that then reveals what you love and what you want to go home towards, what you want to cherish, is what is evoked when I…

JHOh, yeah.

EV…hear you read these words. That’s the love and longing. It’s the very visceral, painful love of things breaking apart. And I feel that that needs to be looked at as much as the need to return to a sense of shared kinship; but also when we have removed ourselves from that. And that is a form of love too.

JHI think you are absolutely right. And I think the poem, you know, the poem almost says it in that very first line: “Break anything—a window, a piecrust, a glacier—it will break open.” So yeah, it’s not something— Because I was so deep in the grief of it, it’s, you know— There is a term in literary theory called “the intentional fallacy.” And what that means is, the author doesn’t always know what the poem says. The author is not the total authority on what a poem means. And as you described what you are hearing in it, I nod to that. And I’m glad it’s not as terrifying— For me, you know, the idea— If Death were an orphan, what would it mean for Death to be an orphan? It would mean there would be nothing alive. That, to me, is the darkest sentence I’ve ever written.

But it’s not over. You’ve got, you know, right before that—”Burning Ones” is us—”Rock said, Burning Ones, pry your own blindness open.” So this poem, very much like “Let Them Not Say”—something I often say when I read that poem, and didn’t this time—both these poems by their existence are trying to make themselves incomprehensible in the future. They are trying to change the tiller of our human actions and decisions by saying, look, it could burn. And if you feel that; and if you feel, as you have been saying so rightly, an abiding love for the beauty of this world that you can’t help—orcas, thistle, kestrel—how can you hear those words and not feel the astonishing beauty of existence? And so, yeah. If the poems let people feel the grief and the loss of it, the hope is we will then become a little less self-serving in immediate ways and a little more find ourselves in service of the love and the large and the intimate and the shared future beyond our own lifetimes.

EVJane, it’s been beyond a pleasure to speak with you today. Thank you so much, and for sharing your poems and your words with us.

JHWell, it has been a joy to have such a genuine conversation. And I, again, thank you for inviting me to do this, and I thank you for everything that Emergence is bringing into the world with its foundation in the great breadth of the Sufi tradition. Thank you.