Bernie Krause, ©2021 Masha Karpoukhina for Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain

Earwitness to Place

by Erin Robinsong

Erin Robinsong is a poet and interdisciplinary artist working with ecological imagination. Her debut collection of poetry, Rag Cosmology, won the 2017 A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry. Her chapbooks include Liquidity, and her work has appeared in Lemon Hound, The Capilano Review, Effects, Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry, and many others. Originally from Cortes Island, Erin now makes her home in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal.

Bernie Krause is a renowned musician, bioacoustician, and a central figure in soundscape ecology who has been recording and archiving wild soundscapes for over fifty years. His many albums include Citadels of Mystery and In a Wild Sanctuary. In 1968, he founded Wild Sanctuary, an organization dedicated to recording, archiving, researching, and expressing the voice of the natural world. His books include Wild Soundscapes: Discovering the Voice of the Natural World and The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places.

In this interview with Bernie Krause, poet Erin Robinsong speaks to the renowned musician and bioacoustician about biophonies of place, practices of earwitnessing, and the intimacy of listening.

Musician, author, and bioacoustician Bernie Krause is a central figure in soundscape ecology who has been recording and archiving wild soundscapes for over fifty years. When he began in 1968, he had no idea how radically the multispecies sound worlds he was recording would transform over the next decades; over 50 percent of the soundscapes in his archive have since been so altered by human activity, they no longer exist in the wild. His archive—based on recordings of entire biomes rather than single-species sound signatures—is one of the largest of its kind in private hands. Now in his eighties, Bernie exchanged emails with me about what it has been like to be an earwitness to biodiversity loss.

When we spoke before our interview, Bernie told me that studying the environment without listening to it is like studying film with the sound turned off. In a visually dominant culture, the implications of becoming an articulate listener are immense and can tune us into a much deeper relationship with the living world. Listening is intimate—sound literally touches us as vibrations—and when the voices of specific species disappear, as they are displaced or go extinct, this particular intimacy goes too. As he said of his exhibition The Great Animal Orchestra: “The basic message is that the soundscapes of the natural world are the voices that we need to hear in order to moderate our behavior.”

Bernie’s account is gorgeous, urgent, and may alter the way you hear the world. In our conversation we discuss what listening can tell us that looking can’t; how every organism produces some kind of sound and every place has a voice; why science and art belong together; what it was like to lose his home and archive to the California fires; and more.

Punctuated with recordings from Krause’s archive and a song from musician and composer Cosmo Sheldrake, this interview invites you into Bernie Krause’s extraordinary yet immediately accessible way of engaging with the world through sound and vibration.

Interview

Erin Robinsong: Bernie, you’ve been listening deeply to nonhuman voices over the last fifty years. Accounts of this historical period tend to center a certain species: the human. I often think, If other species were writing the history books about this time … You’ve been helping them do that, in a way, as an earwitness and an archivist to this history, during the most precipitous drop in biodiversity in the last ten million years. I wonder if you could start by telling us about a particular place (or places) that you’ve recorded over several decades, and the sonic changes that you have witnessed?

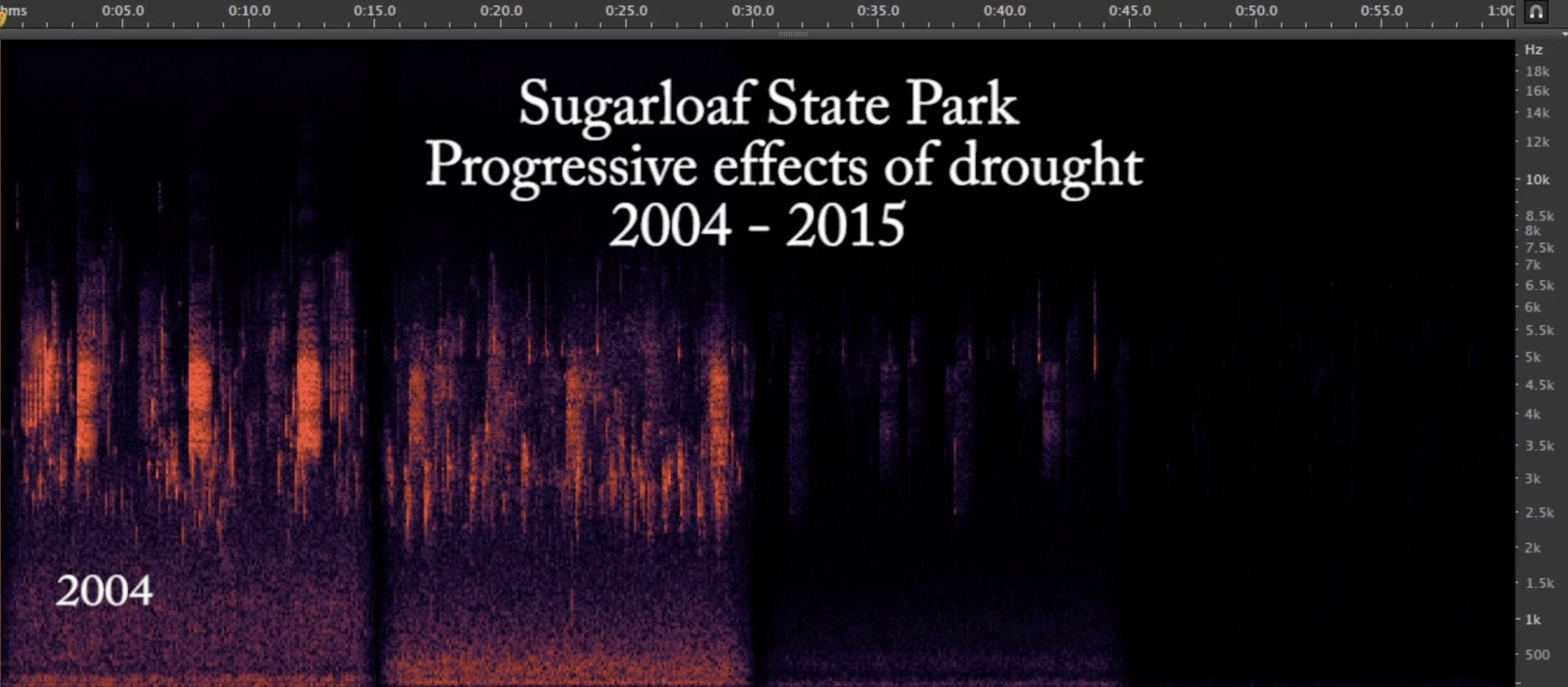

Bernie Krause: The one place that most powerfully illustrates changes in biodiversity, due in large part to global heating, is a site where I’ve been recording each spring since 1993, a place called Sugarloaf Ridge State Park (about fifty miles north of San Francisco—located in a low-elevation mountain range that borders Napa and Sonoma Valleys). It is located in the Valley of the Moon, about a twenty-minute drive from where my wife, Kat, and I now live. I’ve reduced these audio recordings down to four 15-second examples for a total of one minute and created a video of the related streaming spectrogram, a graphic illustration of the sound. The spectrogram illustrates shifts due, in part, to issues associated with global warming.

This short example pertains to the California drought and shows, over an eleven-year period, its impact on the biophony in this area. In the spring of 2015—because of the drought—we experienced what was virtually a silent spring, with no birdsong, for the first time in living memory, even at what normally would have been the height of the season in mid-April. What is most remarkable and peculiar is that very few people in this area have as of yet commented on the stunning paucity of birdsong, now in its tenth year.

The video powerfully illustrates how the issues of climate change and drought have progressed in one location over the course of one decade. The first segment was recorded in 2004; the second in 2009 (five years later); again in 2014, the third year of drought; and the last in 2015.

These recordings were made in exactly the same spot, in mid-April, with carefully calibrated and repeatable settings, same protocol and same equipment year after year. The lower half of the spectrogram shows the signature of a nearby stream, which was flowing pretty normally in 2004 and 2009. The upper half is filled with several different species of birds (note how the species present in that habitat have found frequency bandwidth above that of the stream signatures). The 2004 audio example was similar in density and diversity to other examples from the period between 2001 and 2011 at the same spot. In the 2009 segment, however, the bird vocalization density had dropped off a bit, likely due to the spring season occurring two weeks earlier on average. But the stream was still flowing. In the 2014 segment, however, everything had changed. Three years into the most serious Northern California drought in twelve hundred years, the stream was no longer flowing and the bird density and diversity had dropped off to very low levels. The 2014 example shows something even more interesting; the avian diversity has shifted, with new species occupying acoustic niches that the stream signatures once occupied and several of the other species no longer present in any numbers. This confirms an earlier assumption posited in the acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH) that is predicated on vocal organisms finding unoccupied acoustic bandwidth within which to generate sound.

Spectrogram Video of Sugarloaf Recordings

ER: Wow. And have you continued to record there since 2015? What is the situation there now?

BK: I record there every year about this time. Oddly, after the recent spate of fires, and even with the drought still happening, some of the birdsong seems to be returning. Nothing like the previous density or diversity, but nonetheless present.

ER: What can listening to a place tell us that looking cannot?

BK: Seeing is a relatively passive event. Hearing, on the other hand, is almost entirely physical; component parts of our being respond to incoming waves of air pressure, oscillating in cyclical patterns that are transformed into meaningful signals, indicators that are life-affirming and comforting, or irrelevant, or predictive of danger. Every living organism produces some kind of signal. Hearing those impressions, however faint, either completes what we see or supplants seeing entirely. Because we’re a visual culture we tend to believe all that we see (“seeing is believing”). But, as Saint-Exupéry wrote in Le Petit Prince, “L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux” (What is essential, is invisible to the eye).

ER: Hearing is more like touch when you describe it like this. Can you elaborate on what you mean by “every organism produces some kind of signal”?

BK: Every organism produces some kind of acoustic signature. Some with their voices. Some by stridulation (rubbing wings or other body parts together). Some, like fish, with their swim bladders, teeth, or the oscillation of their caudal (tail) fins. And some create a signal through their metabolism. About twenty years ago, Matt Cooper, a researcher at Cambridge, even recorded the rupture event of a herpes virus. A rupture event—a spike-like signal—occurs when a virus releases itself from a T cell.

ER: The musician Cosmo Sheldrake—whom we know in common—told me a story about a cuckoo you recorded singing over the grave of composer Benjamin Britten, a recording that is now part of Cosmo’s version of Britten’s song “Cuckoo.” Can you tell us about how that came to be?

BK: Britten just happens to be one of my favorite twentieth-century composers … especially his operas. I rarely visit cemeteries, but since I was invited to give a presentation at Snape and was staying nearby in Aldeburgh, I went to visit the graveyard behind St. Peter & St. Paul Church, where Britten and his partner are buried. It was still a time when I traveled with a recorder in hand or pocket. The moment I got to the gravesite, a cuckoo began to sing. Even though it was some distance from where I was standing, I did manage to record the song, which immediately brought to mind the piece of music Britten had written about the cuckoo, and which Cosmo Sheldrake has brilliantly recorded as a duet with the bird I happened to capture that day.

ER: What happens when we listen deeply to biophonies on their own terms?

BK: To the extent that I’ve learned how to listen, biophonies confer to me a strong “sense of place” in much the same way that the late author Wallace Stegner describes in his essay of the same title. Biophonies become narratives that deliver indications of habitat health and stress levels through the collective expression produced by the density and diversity of voices present in a given habitat.

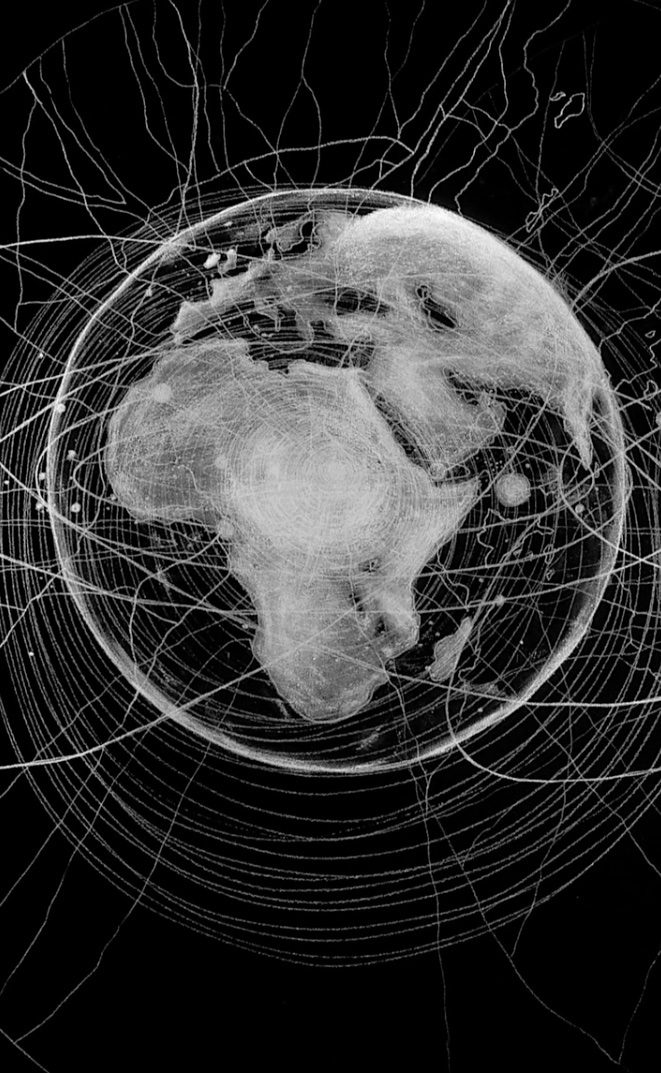

In The Great Animal Orchestra, I mixed soundscapes so that each of the seven environmental examples reveals its own unique story. I utilize avian and mammalian textures, rhythmic patterns of insects, melodies of birds and marine mammals, and reptiles and amphibians to round out different aspects of the accounts. With minimal text, visitors to the exhibit are spared the distraction of explanation. The performances, enhanced by closely related streaming spectrograms (graphic illustrations of the biophonies), are delivered in a biophonic protolanguage that all people—no matter what their age, language group, culture, or gender—can instantly and nonverbally grasp.

ER: Nonverbal understanding is a very interesting form of knowing, especially when it comes to sound. Let’s try it! Is there a soundscape you could share with us?

BK: I recorded this just before dawn in a tower at the end of a dock at Camp Leakey, an orangutan rehabilitation site in Borneo. The lookout rises some fifty feet above the black water of Sekonyer River that flows by the site, just high enough that it aligns midway up the sumptuous canopy, where gibbons and other primates in the area spend most of their lives. The gibbons of Indonesia are sunrise singers. Their songs are so beautiful that ancient Dayak myths speak of the sun rising in reply. In the remaining viable rainforest habitats of Borneo and Sumatra, every dawn chorus is filled with the near-field and distant strains of long descending and ascending vocal lines, as bonded gibbon pairs connect through elaborately developed vocal exchanges unique to each couple; alluring duets of affectionate concord.

ER: What a way to start the day. And it’s an incredibly busy scene—I hear so many other creatures in that recording as well. This biodiversity reminds me that living with strangers who aren’t “like us” seems to be how life works here. Monocultures don’t occur naturally. There are so many ingenious ways on this planet to make a living that sustains life instead of depleting it. You’ve shown how this occurs in soundscape ecology as well, with your acoustic niche hypothesis. Could you tell us about how a crowded sonic environment organizes itself so everyone can be heard?

BK: The signals emanating from organisms large and small in a given habitat must find clear acoustic bandwidth in order to efficiently transmit and receive information germane to their sound-generating behavior. I’d love to take credit for some of that. But, alas, it was the Others who mentored me. The acoustic niche hypothesis (ANH) was an observational take on what I first began hearing in the early 1980s. The signals were highly organized bioacoustic arrangements—especially those that occur in healthy equatorial rainforest habitats. I came to realize that over time each species finds its own frequency or temporal niche, within which it attempts to send and receive signals with minimal interference. With most biophonic spectrograms drawn from healthy equatorial habitats, patterns of acoustic signals are so clearly defined that they often remind me of a musical score created by the twentieth-century French composer Pierre Boulez.

“Every living organism produces some kind of signal. Hearing those impressions, however faint, either completes what we see or supplants seeing entirely.”

ER: Now I’m listening to Boulez … It makes me realize I haven’t been in a healthy habitat of any kind for a while, though I do hear birdsong every day from my apartment in Montréal. What kind of music would you compare urban soundscapes to, if any? Can you discuss biophony in the context of an urban or unhealthy/damaged habitat that you’ve recorded?

BK: I was never much interested in urban soundscapes, mostly because they generally made me feel unwell. I guess the closest experience with music would be some of the early experimental synth recordings that emerged when the analog synthesizers first appeared on the market in the 1960s. Some of the timbres were really abrasive to me—especially as they were amplified by the effects of the ADHD I had to endure. These sounds were partially what drove me into the woods in the late ’60s with our album In a Wild Sanctuary.

ER: That sounds very healing. Did it help with ADHD?

BK: Afflicted with ADHD since my childhood, I found very few human resources that I could turn to for help to mitigate the effects of that condition. I tried everything: therapy, medication, yoga, special diets. None of the more common routes seemed to work. It took me almost until midlife before I understood that the environments most obliging were those of the natural world. (The Japanese made a similar discovery with the practice called Shinrin yoku, or “forest bathing”—a term that emerged in the 1980s.) Of course, they, like us, came to this idea very late. It’s been around for millennia—particularly with indigenous, tropical forest–dwelling cultures that still live in close connection to the natural world. To sit for a time in the depths of an old-growth forest with the fresh, piquant scent of conifers after a rainstorm, the zesty smell of living earth, the cool, humid feeling of the air on your skin; or to hear the trickle of a nearby stream or the rhythmic edge tones of a raven’s wingbeats as its arced flight above the canopy defines the unique space of a habitat that stretches way beyond the boundaries that our eyes, alone, are able to reveal—these special moments infer the closest links to the Divine that we may ever realize.

If that all sounds a bit too anthropomorphic, I am delighted to remind my colleagues that I can’t help it. My morph has always been anthropomorphic.

ER: You’ve moved between worlds with this work—from music and film to academic research and major exhibitions, and of course your ongoing fieldwork and archive. How is art related to bioacoustics for you? How important is it that they speak to each other, overlap?

BK: In my role as a scientist, I still feel that scientific discovery demands a strong element of “art.” The techniques of the craft involve insight, creativity, the ability to transform (sometimes) arcane concepts and conclusions into language that’s accessible, at least to colleagues. That said, if I happen to write and publish a paper, perhaps a dozen peers may read it. However, when I convert that data into works of sound art, such as The Great Animal Orchestra, and generate directly related streaming visuals to support the soundscapes and the media through which they’re transmitted, the performances reach across all cultures, ages, and language groups to an extremely large audience. Natural soundscapes eschew cultural bias.

ER: What has listening to animals taught you about how to rebuild after catastrophic events, like fire?

BK: For me to have arrived at this point in my life with any measure of health and with the feeling that there is wonder yet to be discovered with each passing day is a direct consequence of my intimate engagement with the natural world, and especially its voice. Without that waypoint on my compass, we’d likely not be having this exchange.

But I have no idea what it means to rebuild in what has become a serious fire-prone area. What does one rebuild with? What does one rebuild for? We’re also seven miles (eleven kilometers) from the Rodgers Creek Fault, an earthquake fault that hasn’t triggered in over a hundred years in this area. So, we’re traveling light now: just enough forks, spoons, plates, and cups to eat and drink with; just enough clothes to grab in the event of another firestorm; cat containers always at the ready and at the door; and a couple of towels and a first aid kit with enough food and water for a few days in the car. Looks like we have it all together, right? OK. Any suggestions on where we might go if we have to split this joint?

ER: I would say come to Canada, but we are having huge fire seasons now too (in British Columbia). Living in a fire and earthquake zone is no joke. I know you lost your house to fire in 2017.

BK: Yes. In early October 2017, my wife, Kat, and I lost everything in the wildfires that destroyed large areas of Northern California: Our home in Glen Ellen. Our dear cats, Seaweed and Barnacle. All my detailed field journals, going back half a century. Slides and photos of work in the field. Reference books. Nearly seventy years of historic correspondence. The wonderful sounding Manouk Papazian guitar I played at Carnegie Hall as a member of The Weavers. Fine art. Clothes. Furniture. The intensity of the inferno was so great that even the refrigerator and the engine block of Kat’s car melted into unrecognizable puddles of stainless steel and aluminium. Of everything we had amassed over the arc of our lives, not one single item survived. Without warning from first responders, county, or law enforcement agencies, we were mercifully awake at two thirty in the morning on the ninth of October when the hillside outside our front door suddenly burst into flame, and we fled Wild Sanctuary, our home of twenty-five years, for the last time.

Kat, who had just returned home from a total knee replacement, was completely traumatized, needing assistance to get to the car. The fire was so intense, we left behind all of our personal items: computers, iPhones, glasses, and medical aids for Kat’s surgical recovery. During our dicey pre-dawn flight, with only the clothes we wore, we came face-to-face with the malevolent eye of global heating and its horrific consequences as we bolted through the wall of flame that had enveloped our driveway—our sole one-lane path to whatever life now remains to us. As we raced toward the car, a fire tornado seethed with a voice of rage, a sound I’d never heard before and hope never to hear again: the combined sucking roar of wind and blistering heat, signified by a ferocious expirational crackling surge, while the propane tanks of neighbors exploded all around us. The intensity of the inferno was a humbling reminder of feral power and the absolute certainty that natural forces will always triumph in the end. That sound haunts us to this day; I rarely make it through a night without awakening to frightful sonic nightmares.

Our home, Wild Sanctuary, was a place where we were greeted nearly every day with the numinous voices that arose from various blends of thirty-two species of birds, a family of foxes, bobcats, several coyotes, reptiles, amphibians, lots of insects, and even a mountain lion that occasionally visited us—all making their sonic presence known from time to time. What made our home sacred was a serene consonance of the seasonal cycles, moments heightened by the captivating biophonies that arose from our tiny oak woodland.

With all the “stuff” gone now, the tranquil soundscape that once existed remains the feature we miss the most. It, too, is gone. It was from the voice of our special animal orchestra that we knew the time of day or marked the progressive phases of the seasons. From messages inherent in those distinctive narratives, we became intimately familiar with many aspects of the small bit of earth that we affectionately occupied. Now, something is missing. Wild Sanctuary is eerily quiet. With the loss of that voice, our sense of well-being has palpably suffered as we have moved tentatively and with little choice into a future of unfamiliar and uncertain diasporas.

Special thanks to London-based musician, composer, and producer Cosmo Sheldrake for permission to share his “Cuckoo Song.” Cosmo collaborated with Bernie Krause at The Great Animal Orchestra exhibition at Foundation Cartier in Paris. In 2019, he released a series of Wake Up Calls, pieces composed entirely from recordings of endangered British birds.