Documenting Shifting Landscapes

Kalyanee Mam is a Cambodian-American filmmaker whose award-winning work is focused on art and advocacy. Her debut documentary feature, A River Changes Course, won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize for Documentary at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and the Golden Gate Award for Best Feature Documentary at the San Francisco International Film Festival. Her other works include the documentary shorts Lost World, Fight for Areng Valley, Between Earth & Sky, and Cries of Our Ancestors. She has also worked as a cinematographer and associate producer on the 2011 Oscar-winning documentary Inside Job. She is currently working on a new feature documentary, The Fire and the Bird’s Nest.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His first book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this conversation, recorded live at our Shifting Landscapes exhibition last year, Emergence executive editor Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee speaks with award-winning Cambodian-American filmmaker Kalyanee Mam about her process of creating Lost World—a short film that shares the story of a Koh Sralau community whose livelihood is threatened by ruthless sand dredging. Talking about the importance of documenting the shifts in our outer landscapes as a way to understand our changing inner relationship with the Earth, Kalyanee shares how her intimate experiences with people and places while filmmaking have rooted her in spiritual connection with the landscapes of Cambodia.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeGood morning, everyone. Nice to have you here with us. My name is Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee. I’m the executive editor of Emergence Magazine. I’m also the curator of this show. And I’m delighted to be in conversation with one of our artists, filmmaker Kalyanee Mam, who has come all away from California to be with us this week. Welcome, Kalyanee.

Kalyanee MamThank you, Emmanuel.

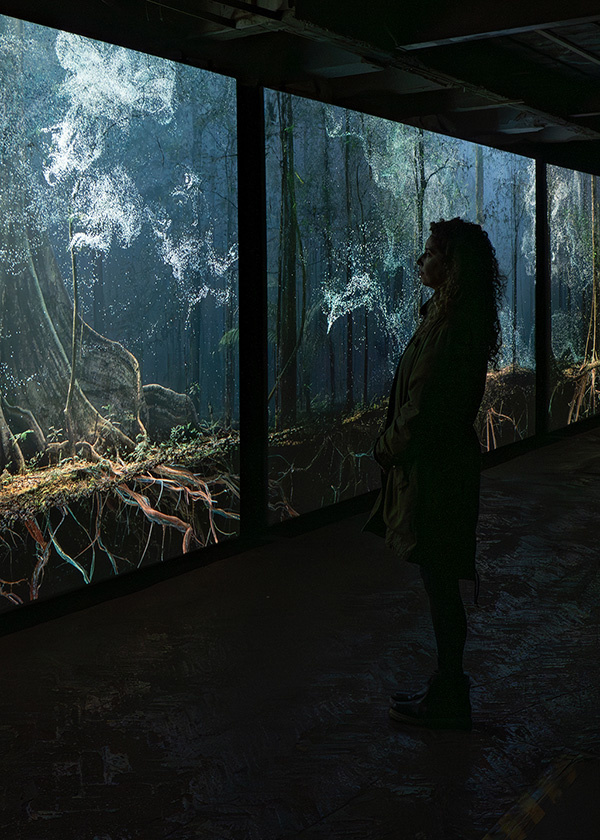

EVSo this morning we’re going to talk to Kalyanee about her work, which is being exhibited downstairs: the film Lost World and a companion set of photographs. Many of you may have already seen the work and watched the film. If you haven’t, then after our conversation, I highly encourage you to head downstairs and to watch this powerful, powerful piece of work.

Kalyanee and I have known each other over ten years now, and we first met while we were finishing both of our first feature films. A mutual colleague had seen both our work and after seeing the films felt like we should connect. And we met over coffee, and I think three hours later we were still drinking that same first cup of coffee, because we hadn’t drunk anything, because we were just talking. And there was so much that we shared and that we felt was important to explore through filmmaking and storytelling. And we’ve been fast friends and collaborators ever since.

And I was lucky enough to serve as a producer on Kalyanee’s film Lost World and work with her to create this really, really powerful—at times heartbreaking—story of shifting land. I mean, in some ways, the film that Kalyanee has made really brings to light the theme of shifting landscapes in a more potent way than perhaps any other work on display here. It’s a story, if you haven’t seen it, of one of the most beautiful places in Cambodia—Kalyanee’s homeland—that is literally being mined of its sand to build a new world in Singapore, an eco-park. And there’s something really quite tragic, and ironic perhaps, about that—that people are mining sand and destroying mangroves, and a people’s way of life that’s been dependent on those forests and those rivers for millennia, to build an eco-themed park so people can experience nature.

There’s extreme hubris present in that story. And it’s also very much a human story. It’s not just a story of land, but of people’s relationship to land, communities’ relationship to land. And it’s told through the story of this young woman who is an essential character and leads you on this journey to experience her relationship to land in these shifting landscapes that are unfolding. So it’s a powerful work. So thank you for that work, Kalyanee. Thank you.

Just a brief introduction to Kalyanee. Kalyanee is a Cambodian-American filmmaker who has been telling stories about her homeland for two decades now—stories of the shifting landscapes on many levels that are unfolding there, ecologically, culturally, socially, politically, economically, and specifically people’s relationship to land and community and how that’s evolving at this time of great change.

Her first film, A River Changes Course, won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, and Lost World was a Critics’ Choice nominee. She’s currently working on two feature films: The Fire and the Bird’s Nest, which she’s been filming for five, six years now. I had a chance to actually go with Kalyanee to Cambodia in February and meet the family that she’s been living with for all these years and filming. And also a film, Taste of the Land, which is a new film with Kalyanee’s sister that she might speak a little bit about as we learn more about her work.

So I really want to start our conversation, now that I’ve introduced a little bit about the film and its story, with its origin and what led you to want to tell this story and how it came to you.

KMThank you, Emmanuel. You say the word “origin,” and I’m so appreciative of that, too, because I’ve been thinking about origin and feeling the origins, the origin of my ancestors. And the word cheate in Khmer means “taste.” And the word roukkhcheate means “flora.” The word thommocheate means “nature.” Brates cheate means “country.” And all of those words have one word in common, which is “taste,” cheate. So in order to know the land, in order to know where you come from, to know your origin, you have to understand and feel the taste. You need to taste the land. And this is what we’ve been doing in this exhibition: tasting the land, tasting the forest, you know, tasting the sound of the nightingales, tasting the honey. And each of those experiences has brought us closer, closer to our origin. And it’s so interesting because cheate, doeng cheate, where we skal cheate, is “to know your origin.” So the word cheate also means “origin,” which is what I just realized, actually, a few weeks ago; I didn’t make the connection. But yeah, to skal cheate aing, “to know your taste” is to know your origin, literally.

And it’s been a long journey for me, because as Emmanuel mentioned, my family and I made a long journey from Cambodia. We fled the Khmer regime. I was born during the Khmer Rouge regime in 1977; that regime lasted from ’75 to ’79. Over two million people were killed, either by execution or starvation. And our family went through many challenges in order to escape this regime and to come to the United States.

But during that journey, I also lost something. I lost, you know, my family and I lost our homeland, and we also lost our taste. The taste for the land that gave birth to me and my family. And I thought I lost it. But over the years, what I realized was that the taste had always been with me all along. And the people who helped me to realize that were the families I met in Cambodia, who I spent many years with learning about their way of life, their connection to the land, and to the rivers and the forests. And especially Reem Sav See, the family that Emmanuel got to meet in Areng Valley—they taught me so much about the land and how precious this land is for their livelihood, for their sustenance, for their nourishment, for the way they see the world—it’s completely influenced and inspired by that landscape.

And what also made me realize that the taste was with me all along was my mother. Growing up in the United States, at the very beginning, we had no access to lemongrass or ginger or turmeric, you know, and all the herbs that made our food. And, Maak, you know, she had to find her way. She went to the— In Texas, she went to the Mexican grocery store, and she bought boxes of vegetables and brought them home and shared that taste with us. Even though it didn’t come from our homeland, she was able to share the taste of fresh fruits and vegetables.

And then when we moved to Stockton [California] and we found a Cambodian community there, we went to the farmer’s market and she shared even more with us. And she taught us the names of all the fruits and vegetables, and the herbs: lemongrass, ginger, turmeric; marah, which is bitter melon; throp, eggplant; sloekakrei, lemongrass; khnhei, ginger. We learned all these names through the food that we tasted with her. And so through my mother, Maak, I learned Khmer language, which gave me a window into the Khmer taste, which gave me a window into our homeland, and a window into our ancestry, and the bloodline that flows through our body. And that’s how I learned to appreciate the land. And that’s how I learned to want to protect this land and to continue to live with that land.

And so that’s origin. And that is something that I feel is within all of us. You know, each one of you have that taste too. We need to just revive it. How do you know to protect the forest if you don’t know how tasty those fruits are; you know, those mangoes that come from the forest are? You will protect it if you want to taste that mango again. And you will protect the Epping Forest—which I had an opportunity to walk through with my friend, Fran—if you can taste the mushrooms that grow there.

EVWell, that’s your origin story, which I think is wonderful to share—or a part of your origin story—to share as a backdrop for why you tell stories in the way you tell stories. And you spoke of protecting the land. Now, Phalla, the main character in Lost World, she is trying to protect the land. And if I remember correctly, when you shared the story of how you met Phalla—and perhaps you could share that story here—it was through her protection of the land that you first encountered her and were inspired to tell her story and the story of what was happening there. Could you talk about that?

KMYeah, so I was working in Areng Valley, filming See and her family, and I got a call from Alex Gonzalez-Davidson, who was the director and founder of Mother Nature Cambodia, a local grassroots organization of activists fighting to protect the land in Cambodia from hydroelectric dams, from industrial agriculture, from displacement of people from their lands. And he said, you have to go to the mangrove forest. And I’ve been to the mangrove forest before. Actually, David and I—my husband—we went when I was filming A River Changes Course, and I remember how beautiful it was. But I never realized how extensive and grand this stretch of forest was until I went there for the first time with Mot Kimry, a young activist who was also part of Mother Nature Cambodia.

And we took this journey together. We got in a boat and then we just went for like miles—or kilometers in Cambodia—many kilometers, stretches of mangroves, forest after forest after forest. And I was just astounded. I couldn’t believe how extensive this network was. And then when I learned about the mangrove forests and how important they are for the ecology and the ecosystem and then for our coastline, I was even more blown away.

And at first, I mean, I didn’t really go in with a plan. I never have a plan. I didn’t at all know what story I was going to tell. And I went into the community, and we lived with Bong Chen and his wife and his children. And then one day, he said, do you want to go out to where the sand dredging is taking place? And I said, of course.

And so we went out on the boat. And when you go out, you don’t just go out as activists or, you know, as experts. You go out as a family. So Bong Chen was there with his children and Pou Mok was there with his child. And so the whole family went: wife, children, everyone. And Phalla, who’s also part of the family, was there as well. And she just like— I had the the mic on Bong Chen and his wife, and after maybe a half an hour I was like, maybe I need to switch the mic to Phalla. And all of a sudden, we went and we were like—we had the boat going towards where the sand dredging was taking place—and all of us, I mean— They’ve seen this almost every day, because they were monitoring all the sand dredging. They were monitoring how deep the water was, how deep they were dredging the sand. And it was deep: many, many meters underneath the ocean. And the reason why they dredged so deep is so that they can get the finest sand.

And so we were watching them dredging, the excavators going in and pulling out the sand, and the sand’s just dripping from the excavators, you know, the arm. And all of a sudden, Phalla started singing. And she sang in this beautiful voice, this song, as we’re watching the sand dredging taking place. And she just sang and sang. And I put the camera down. I was filming her for a little while, but I decided to put the camera down and just appreciate her voice. And then I held her in my arms, and I just cried.

And she sang the song in the film, you know, about the land, about the mangroves, about the people, about this garden, this beautiful, natural garden, not built by human hands but that comes from Her—Mother Earth. And she sang this song, and it was just so beautiful. And I just knew at that moment that we needed to tell Phalla’s story.

EVCan you talk a little bit about your process of how you tell stories, because you spend a long time in each place that you visit, and just in sharing the story now, you’re sharing the names of everyone that you’ve met. I think there’s something really important about that. You’re sharing the names. They’re real people that you spend time with. You know their stories; you know their families; you know these villages; you’ve come to know their histories, because you spend a lot of time there. And you’re not always filming. In fact, I’ve come to know that you film a lot less and have a lot more time hanging out with the families and the places. But that’s really important because it’s part of the process that you go through about building a relationship. And it seems less like the filmmaker telling a story, versus a friend, a family member even, who’s spending time there and being a conduit perhaps— So I wonder if you could talk about your story and what unfolds over the years that you’re there in these places. Because even in this film, which is a short film, it took several years for you to film.

KM[laughs] Yeah, I don’t know how frustrated the grantmakers are by me, but… [laughs]

EVAnd producers.

KMAnd producers. And editors… Oh, it’s um— Thank you for asking that question, because the process that I just love so dearly about filmmaking— You know, making a film is actually only an excuse for getting to know amazing people and eating delicious food. So, like I said, I don’t really go in with a lot of plans, and this is probably why it takes so long. I just enjoy the magic of the unfolding, and just being in a place and really getting to know the place and the people.

And the people and place are one. This is the thing: the people who are telling the story—they live there, and this is their life, and their life is slow and beautiful. And, you have your heart against your heart. And I feel this, you know. Their life is so intertwined with everything around them. And so they feel everything and they taste everything. And I feel the only way that I can tell that story or help them—not me telling their story—but help them share their story, is to be in the same space; the same sense of space and time that they are in. And whether I wanted to or not, I felt like I really wanted to immerse myself.

Bong Chen, who we stayed with while we were filming, took me to Lover’s Island, like maybe three times. And Lover’s Island is the island that you see in the film at the very end when Phalla is sitting at the boat and she’s looking out of the island. It’s a very special place. It’s called Lover’s Island—Kaoh Sentiment, Kaoh Bong Kaoh Ohn, which means: bong is the word that you use to refer to your husband, and ohn, or your lover, who is, you know, older than you. And then your ohn is the darling, you know, and the other lover. And so Kaoh Bong Kaoh Ohn, when the tide pulls out, it becomes one island. So Lover’s Island is one island. And then when the tide is high, the island becomes two, and then you can see that they are lovers.

And the story was that they went out into the ocean, and they went crabbing and looking for crabs and fish. And then all of a sudden, the tide came in, and they drowned. But before that, they vowed to remain lovers for the rest of their lives. And so they’re still lovers now. So I was inspired by that story, and I wanted to just feel the place. And so I would go out with Bong Chen all day. We would go out on the boat, and people—the community members, you know—would be like, So, Kalyanee, where are you going today?

Uh, Lover’s Island.

What, again?

And even one night we went out and did a time-lapse. We set up the camera early in the day on a tripod and put it in the ocean when the tide was low, and we put up lights in the trees and the mangrove trees. And then we spent the whole night just watching the stars.

We did nothing with the time-lapse footage [laughs], but I just enjoyed being there. And it was just, yeah, it was just beautiful just to be there and to— You know, if I just flew in for a week or two weeks, or even just a month, I would not know; I would not be able to feel the rhythm, the rhythm of the life, the rhythm of the tides, the rhythm of the sunrise and sunset, and the rhythm of people.

You know, London has a rhythm, and it’s really—it’s very tense. But Lover’s Island has a very soft and gentle and sweet rhythm. And the only way that I can feel that rhythm and that heartbeat of that island is to give time and space for it.

EVWhen you spoke about your origin briefly a few minutes ago, you imparted the importance of the taste of the land, right? Cheate. And of course, that is about place. And, you know, all of your work really is about place: A River Changes Course is where you follow these three families over many years; Cambodia, as a whole country; these individual regions each family is from, their changing relationship to place as economic development and ecological devastation result in a shifting way of being in relationship to place. But Lost World perhaps is more directly—at least I find—about place. Was that something that was revealed to you through the process of spending years there with Phalla and visiting Lover’s Island, or did it become clear early on that this was a story about place that needed to be told in a more direct manner?

KMYeah, yeah. Actually, I don’t know if you remember this, but we had a conversation while I was in Cambodia. I think we were on the phone, but I just remember us talking about the possibility of going to Singapore.

EVRight, I do remember that conversation.

KMYeah. And usually, you know—like in A River Changes Course or Fight for Areng Valley—I never really wanted to show the adversary. And I hate calling it “adversary,” and I’ll explain that later. But I wanted to show and really put attention and focus on the people and their way of life and the land in the forest and show that beauty and immerse us in that beauty in that place.

And I remember when we had a conversation about the possibility of going to Singapore, Emmanuel, you really raised that possibility as an important one. You know, because in this film in particular, in order to show the devastation, we had to show what was— why this devastation was taking place. And we had to show the outcome. Where was this sand going? You know, this sand, this precious sand that came from the mangroves. Where was it going? What was being done with this sand? And we needed to answer that question. And I’m so happy that we did. Because by showing the contrast, by showing what happened to the sand, we could see the hubris, as you mentioned. We could see the devastation. We could see how, even reflected in the space that we’re in here in London, what kind of havoc and destruction we have done to the land with our hands—our human hands, our human desires, our human greed. And I think that question needed to be answered.

EVI mean, sand is—I was just reading about this the other day—is second only to water as the most in-use material in the construction of any building or development. And development of construction is 40 percent of global emissions compared to 25 percent of transportation. And sand is the key ingredient in concrete.

KMYes.

EVIt’s also a key ingredient—

KMIn glass.

EV—in glass, and expanding landmass. And what’s interesting, you know, is that sand dredging is almost an invisible form of extraction, compared to clear-cutting, for instance, or open-pit mining or other forms of extraction. Sand mining is, you know, dredging a river. And you can say, oh, it’s a beautiful place. And it takes time to reveal what’s happening to the mangroves.

And, you know, I remember that conversation, now, of encouraging you to go to Singapore. What I think is so interesting—what you do in the film—is you don’t just take the audience to Singapore and show the destruction with aerial footage. You do that in a very potent way, but you also do it through a very, very intimate lens of Phalla’s experience of coming to Singapore. And if I understand, it was the first time she’d left Cambodia, and you were torn about it. I remember talking to you about being torn about taking her there, but you felt it was the right thing to do.

So I wonder if you could speak more to that, because there’s also a story about your time there that isn’t in the film. In the film, you see Phalla going to the sand depots, going to the eco-park where this strange, strange—they call it the “lost world”—has been created to entice people to become closer to nature. You take her to this; she sees this. But you also did other things. And I’d like— maybe you could talk about the whole experience, because it’s very important.

KMNo, I actually wanted to mention that too. I remember a conversation we had with Phalla, and Mona Simon was with us as well. She did the stunning photography of Singapore. It’s incredible. She really captured that so well. And so Mona and I and Phalla, we were together. And I remember we had a conversation with Phalla, and we asked her how she felt about being in Singapore. And she spoke in such an eloquent way. I wish Phalla could be here right now to speak for herself. But she said to me, you know, she said, I don’t doubt the beauty of this place, and I don’t question the skyscrapers and the buildings. And, you know, they can do whatever they want with their land. But why did they have to take our land to build their land?

And then she also spoke about the skyscrapers and the high buildings. She said, I don’t understand how they sleep at night. You know, up in these high buildings. Our houses, our homes, are close to the water and close to the land. When you’re way up high and you’re sleeping on concrete, how do you feel the land?

I mean, this is a really interesting question. How, if you’re used to sleeping on concrete, how do you feel the land? How do you lay your head at night and know where you are? And, you know, she was just, like, astonished. And then when we were walking through the gardens—and you saw some of it in the film—she would look at every flower. She would smell every flower, and she’s like, What? These flowers have no smell. You know, in the forest, you smell the flower, and they’re so fragrant. In the mangrove forest, she talked about when she was a child climbing the mangrove trees and smelling the blossoms, or walking through the forest to find silence and quiet and peace in the forest. And in this eco-park, this man-made artificial landscape, she couldn’t smell anything. She couldn’t taste anything. She couldn’t even touch anything. There was a sign that said: Do not touch. Many signs everywhere said, Do not touch.

And one of my favorite moments was when she took the camellia in her hand. She was like, Oh, camelia. I’ve always wanted to meet you. And now I finally meet you. She smells the camelia and she says, I wonder if you can make traditional medicine with this. You know, so she’s accustomed to a landscape, a forest, of abundance; not just abundance visually, but abundance in medicine and food and sustenance and nourishment—a forest that gives and receives, that’s interconnected and intertwined with her, her community, and all the living beings and creatures that live there. And this “eco-park” was completely opposite of that. And she was just really stunned. And she actually got a little bit sick. And I think it was because she was in such a different place.

And you know, I remember, also, one time when I was in Areng— Not Areng. I brought See and her aunt to Phnom Penh from Areng Valley, and we screened Fight for Areng Valley. And See and her aunt said that they became dizzy, and they had headaches, because we were staying in a hotel that was on the second floor. And we could feel people on the third floor thumping their feet above us. And See’s aunt said, I can’t stay here, because I can’t have people’s feet above my head.

You know, so these are sensitivities that I feel that maybe we’ve lost, and we’ve become accustomed to the— What’s the word, you know, when you get used to the violence, you get used to the pain and the numbing? You get so used to it that you don’t even feel anymore. Yeah, and for Phalla, she wasn’t used to it yet.

EVNo.

KMSo she felt everything, and everything was just, you know, moving her body.

EVThere’s one thing that isn’t in the film that you did with Phalla, which I think was quite courageous, which was to stop people on the street in Singapore and to ask them if they knew where the sand came from that was expanding the island—with Phalla right there. Can you talk a little bit about that experience?

KMThank you for reminding me of that. You have such a good memory. Yeah, we had photographs. We brought photographs of the mangrove forest with us and easels, and we set them up in the urban landscape. You know, in the middle of Singapore, downtown, we set up the photographs of the mangrove forest, of Lover’s Island—some of the photos that are in the gallery. And people were walking by, and then we had edited a small little clip of the mangrove forests, of Phalla singing the song, and of the fishing and of the people pulling in the fishline and pulling in the crab pots. And people were walking by and they were curious. And now they asked us what we were doing. And so Phalla invited them. And she called everyone “Brother” and “Sister.” She said: Oh, Brother, come, I will speak with you. Oh, Sister, let me tell you a story.

So they would come and they would listen to her, and she would share the story of the mangrove forest. And then she would share the story of the excavation and the sand dredging. And then she would inform them that they are standing on Cambodian sand. They are standing on the land that came from her country, from her land, from her forest. And people were stunned. Nobody, not a single person knew that this was the case. And they were so appreciative of Phalla sharing her story with them. And they told us who they were and what they did, and that they would, you know, spread the word and tell others about the stories that Phalla shared. But it was a really important moment for Phalla to share these stories. And for the people of Singapore. Maybe it was a total of ten or twenty people that we reached out to, but at least ten, twenty people she was able to sit with for a certain amount of time and share the stories and shine a light on what is happening.

Not only in Singapore, but all over the world, land and people are being displaced, removed. You know, first it was people, then it was animals, then it was plants and trees, and now it’s sand. It’s the very land itself that’s being carved out and displaced and taken somewhere else.

EVYou know, listening to you talk about your work and talk about Phalla and her family and Koh Sralau and Lover’s Island and Areng Valley and See, and all these people and places that you spend time in and tell stories about— There’s a feeling of intimacy—I’m sure you can feel it too—that’s present there. And there’s also humility: something I’ve been very touched by in how you approach your work. It feels like you are removing yourself from the center, how far you can get to the side, pushing yourself always to the side. And I wonder if you could talk a little bit about your own journey in getting to that place where you are so intimate with your subjects. And, you know, maybe it’s a little uncomfortable to talk about how you become humble—because a humble person should never talk about that, right? It’s a secret. But you are a humble person, and it’s very moving having seen you, after many years, watching your work through the edit stage and seeing final films and having you talk about it.

But after many years, as I mentioned, I got to go to Cambodia and spend several weeks with Kalyanee while she was there and watch her film and also just watch her be with the families and the places. And, you know, a journey with Kalyanee takes a lot longer, because she’ll stop and she’ll talk to every single person, and she’ll ask them their story. And by the end, the joke is like, she’s been invited to stay at dinner, to be the bridesmaid, because there’s a real genuine connection that you make with people in a space of humility.

So I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that journey that you went on and how conscious it was, or maybe also some of the things that you were challenged by and your own process, and having to look at yourself, and what shifted over the years there.

KMThank you, Emmanuel. So much shifted. And I’m glad you use the word “shift,” because I’ve been thinking about the title of this exhibition a lot. You know, Shifting Landscapes. And the word “landscape” is really interesting because—and this will all connect: I always go in a roundabout way. But, yeah, the word “landscape” is, I find— I’ve discovered it’s very, it’s like distant. You know, you’re looking at the landscape. It’s escape; it’s not a home. It’s not, you know, being immersed in the place.

And I find that I’ve discovered with all the families that I’ve lived with in Cambodia and with my mother, too, that the land is part of us. We cannot extricate ourselves from the land, and the land cannot extricate themselves from us. And the land is a reflection of our innerscape. And who we are inside us is a reflection of the land around us. So the reason why the land is shifting—and of course it’s always shifting— However, the reason why it’s shifting in the way that it is now is because our innerscape has shifted. We have changed in the way that we view and value the land. And this is what I’ve realized with myself, that as I learned to see the land differently, through the support and sharing of the families that I lived with in Cambodia, and through my own greater appreciation of my own mother, I learned that something shifted in me too.

You know, when we came to the United States, as I said before, everything shifted for us. Our physical dislocation resulted in our spiritual dislocation as well. My father lost everything. He lost his home, he lost his land, he lost his family, he lost his role as a father. When we came to the United States, it was very difficult for him to find work. He couldn’t provide for his own family. During the Khmer Rouge, at least he knew his role was clear. He knew that he would protect us, and he would guard us, with everything that he had to make sure that we were safe. So his role was very clear during the Khmer Rouge.

But when we came to the United States, his role was less clear. He really didn’t know who he was and what he represented and what belonged to him or who he belonged to. And my role was not clear either. Because I was forced to leave this, you know, traditional place. And I came to the United States—and I think the UK is the same, the traditions are very similar—and I was taught that I needed to be educated. I needed to read books. I was taught that the English language was more important than my native tongue. And I was taught that in order to survive in the United States, and increasingly in this broader global landscape that we’re part of, I needed to work very hard, study very hard, and leave behind the ancestral wisdom that my parents taught me. And I also needed to have control.

You smile because you understand. I needed to be completely in control of myself. And I also needed to be individual. I needed to achieve and accomplish as an individual. Not as part of a community, but as an individual. And so I worked really hard. I read many books. And I went to school. And I forgot. And I lost. I lost many things that my mother taught me. And fortunately, my mother didn’t lose as much. When we came to the United States, she held on to her mother tongue. She held on to her maiden name. She didn’t change her name. My father changed his name. He changed his name, Sok Sann, which means “peace and tranquility,” to Peter, which means “rock.” So he was struggling to find security and strength in the United States.

And all of us changed our names, because we wanted to belong in the United States. We wanted to belong in this foreign country. But Maak did not change her name, and she did not even learn how to speak English. When I was young, I thought, Oh, Maak, why can’t you speak English? I want to communicate with you. I want to have a conversation with you. And I did not realize the wisdom of her choice. By not speaking English, she forced us to retain our mother tongue and our connection to our homeland, and our food and our taste and our ancestors.

And so I was lost. I didn’t know where I was going and didn’t know what I was doing. All I knew was that I had to get to the top and I had to go to the best university, get the best grades, accomplish everything, and do it all on my own. And I maintained that mentality even with filmmaking.

You know, I have to say, Emmanuel is very generous with his words, saying I was humble. But, no, I was not humble. When I started out, I was an American. I was a white person going to Cambodia believing that I knew what I wanted—what story I wanted to tell. You know, like I had things written down. I wrote notes, notes after notes. I would show it to See. I was like, Okay, See, what do you think of this idea? I’d like to tell the story of da-da-da. And she would just nod her head. You know, all the families were very, very patient with me. I would share books, I mean, notebook after notebook of ideas that I had about what the story was. And over time, I realized: Kalyanee, stop. Stop moving. Stop, you know, rushing. Stop thinking. Start feeling. Start sitting. Start listening. You know? Start tasting. And the moment I stopped and I started, that’s when the stories flowed. And that’s when my ancestors spoke to me. And when my heart was open enough to receive all the gifts—you know, the gifts, the treasures that have always been there.

EVLost World is a story about erasure and displacement of land and displacement of people. But it’s also—and I think this is one of the reasons why you made this film and why you tell stories too—that in telling these hard stories—because they’re painful, especially when you’re as close to the people in the land as you are, because it’s home to you, they’re home to you—that pain has a potency, because it can open our eyes, yes, and we can become educated, but it can also open our hearts, as it opened yours. And one of the things we’re exploring in this exhibition overall is, How do we place ourselves in these shifting landscapes when there is an opening present? When we have been impacted by the pain and the suffering and the grief of these changes? And there is a desire to respond from a deep place inside of us.

I guess my question is, how do you feel we need to, in some ways, bear witness, but maybe also mourn—because there is a space of mourning which is opening up. I mean, the mangroves are never going to be the same as a result of this sand dredging. Phalla moved to Phnom Penh when I was with you. I met Phalla, and she lives in Phnom Penh, and her husband works in the factory, because they needed to make a living and they couldn’t do it in the same way, in the way that their families had for millennia.

I mean, these are big changes that are impacting people in very direct ways: having to move from homeland to city to work in a factory. And these landscapes are changing all around us. And so you spent time in these places, and you’ve felt so deeply in relationship with them, and your stories offer windows for people to go into that space. How should we mourn and be present to these shifting landscapes? Whether that be in Koh Sralau, in Cambodia, or in our backyard? It’s a little harder to see, but they’re in London too.

KMOh, Emmanuel. Amazing question. You must have been in my head, because this is what I want to talk about. Oh, gosh. Grief, loss—those are all so intertwined and nothing can emerge without the grief, and the grief of the loss. And the only way I know how to answer questions is with a story, so bear with me. In April, about six months ago, I was bouldering and I fell, and I dislocated my elbow. And I had to get surgery. I tore my tendon and ligaments there, and it was very painful. And when that happened, I felt the pain that I never had felt before—a physical pain. And I wondered how to deal with this pain—deal—or manage this pain. I didn’t want to take painkillers because it made me nauseous, and, you know, it was horrible to take the painkillers. So I just let it be. And I completely embraced the pain.

And as I embraced the pain, I began to feel my father, and I began to feel the pain that he went through before he passed away from liver cancer. And I learned to appreciate that pain and also his response to it, which was to numb the pain. The pain was so great for him that he had to numb it. He could not just let it be. And it was not just a physical pain for him. It was a psychological, spiritual pain, which is even more powerful than physical pain. And so I learned to have even more compassion for my father.

And then as the months progressed, I saw the wound begin to heal. And now I have a scar from it. The wound was closing in. Actually, after a week, I think, we took out the staples, and I could see the wound open, and I was like, Wow, this wound is really open. And then as the weeks progressed, the wound began to heal and close. And then I realized I was actually witnessing my own wound—not just the physical one, but the psychological wound, the spiritual wound that I had been carrying all my life—finally heal. And it was such an amazing experience. And somehow the pain wasn’t so horrible anymore. It wasn’t so unbearable anymore. It actually became something that I embraced, because I had a newfound perspective for it. It also made me realize that this experience was crucial for me. I had to see this happen. I had to watch time pass. I had to watch the pain pass in order to truly heal. And I could not ignore it any longer.

And I feel this is where we are right now. You know, as part of this beautiful, magnificent world that we are in, this universe, this incredible place. You know, we need to look inward into our own pain, our own loss, our own suffering, and see where we can heal. And by healing ourselves, then we can truly be who we are, which I believe is a complete gift to the world. We cannot be a gift to the world if we feel pain, feel incomplete, feel unwhole, feel like we are not enough. We can only be a gift when we are whole. And I think this is the same for the mangrove forest, and all the forests that are being cut down, all the rivers that are being dammed. We need to find that wholeness again and that connection again. Allow the pain to enter us and to feel the pain, however; embrace the pain as an opportunity to hold one another, to be with one another, to support one another, and heal together.

I remember talking to my mother during the—I think it was before the pandemic, yeah. There was like extreme torrential rains: we call it an “atmospheric river” in California, in Northern California. And then, before that, there were extreme fires. Fires everywhere. In the Sierra Nevada, another homeplace for me; on the Sonoma Coast, another homeplace for me. And I was speaking with my mother and talking to her about all these things that were happening. And I asked her if there were any stories that she could share with me about things like that happening when she was young. You know, floodings or fires. And she said, yeah, there were some dry spells, you know, when we were living in Prey Veng. It would become really dry one year, or become really wet another year. But never anything this extreme. And I asked her, Maak, what can we do? How can we respond to this? And she said, we need to thveu bon. And thveu bon means “to make ceremony.” And I said, what do you mean by that? She said, we need to come together. You know, we need to hold hands. We need to sing songs, chant, pray, share food, make music. We need to be together. And only by coming together will we create the energy needed to heal the planet. And I was just so blown away when she expressed this. And I asked her, Maak, where did this come from? You know, how do you have this idea? And she said, I don’t know. The ancestors, the spirits, spoke to me. So I think what she says is true and this is what we need to do.

And then a day after my surgery, I was in so much pain, and I don’t know where this came from, but I could feel my heart beating very fast. And all of a sudden, I could feel my heart beating with Mother Earth. It was really strange. I don’t know how it came, but yeah, my heart was beating, and I could feel Mother Earth’s heart beating. And then all of a sudden, I saw the forest. I saw the Earth, Mother Earth, and I saw the forest, and I saw the forest respiring, and I saw the rivers and the rocks and the plants and the mushrooms, and I saw us all breathing and sharing one breath. And then a few days ago, when I arrived here, this is exactly the image upstairs. This forest, this breathing forest, was the image that I saw. However, I saw it as the Earth, and I saw the Earth as Mother, and us as Her children. And that image was so strong and clear to me.

You know, scientifically I knew everything that was written upstairs—you know, the synopsis—I knew in my head that this was true; but for the first time in my life, I felt it in my heart. And that is something that you cannot replace, the feeling in your heart. No matter how many books you read, no matter how many stories you hear or images that you see, you cannot replace that with the feeling that you feel when you’re standing in the forest. So I feel in a way that, you know, how do we heal? How do we come together? How do we feel? How do we emerge from pain and grief to healing and beauty? I think it’s by feeling, feeling and touching and tasting and truly connecting with the Earth and the land again.

EVKalyanee, it’s always a pleasure to be in conversation with you. Thank you so much for sharing your stories with us today.

KMThank you.