Another Kind of Time

Jenny Odell is an Oakland-based artist, writer, and educator. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Paris Review, The Believer, McSweeney’s, and Sierra Magazine. She is the author of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, a New York Times bestseller; and Saving Time: Discovering Life Beyond the Clock. Her visual work has been exhibited internationally, including at the Marjorie Barrick Museum, Les Rencontres D’Arles, and Fotomuseum Antwerpen. She has been an artist in residence at the Internet Archive, the Recology dump in San Francisco, and the Montalvo Arts Center and has taught digital art at Stanford University.

Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee is an author, Emmy- and Peabody Award–nominated filmmaker, and a Sufi teacher. He has directed more than twenty documentary films, including Taste of the Land, The Last Ice Age, Aloha Āina, The Nightingale’s Song, Earthrise, Sanctuaries of Silence, and Elemental, among others. His films have been screened at New York Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, SXSW, and Hot Docs, exhibited at the Smithsonian Museum and London’s Barbican, and featured on PBS POV, National Geographic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times Op-Docs. His new book, Remembering Earth: A Spiritual Ecology, is forthcoming from Shambhala in summer 2026. He is the founder, podcast host, and executive editor of Emergence Magazine.

In this conversation, artist and writer Jenny Odell points beyond the domination of clock time toward ways of being that are more in tune with the rhythms and patterns of the Earth.

Transcript

Emmanuel Vaughan-LeeI want to start by talking about language and how language informs how we perceive and relate to time. In Saving Time you explore the social and material roots of the idea that time is money—a phrase we’ve all heard, and one that’s become very entrenched in our thinking and ways of being as a culture, and that influences so many aspects of how we think and relate to time—and that one of the ways we can untangle ourselves from ideas like this is through the use of language and the ways that we write and speak about time. Can you talk about this?

Jenny OdellYeah. I am so glad that you ask that, because I feel like that’s one of the most important things to me about the book and kind of how I’ve tried to explain it as—you know, obviously it’s not self-help, but it’s a book about language. I have always been really interested in how language—and maybe things that you wouldn’t think of as literally being language, but maybe like framings, like frameworks for seeing—have affected the way reality feels. I’ve been interested in that for a long time, because I was also a visual artist for many years, and I tended to try to make work, and I also appreciated other work, that did something with those frameworks. So I talk in my last book, How to Do Nothing, about going to a John Cage performance in downtown San Francisco and walking out of the auditorium and almost being able to hear the city for the first time in the many years that I’ve lived there.

And I think that that can be such a destabilizing, but also really exhilarating, experience: sort of being given a different kind of access to something that was already in front of you all along and maybe it brings out or it defines different things that you weren’t able to see. And I’m just obsessed with that. I’m always chasing that, whether it’s from the point of view of a reader or a viewer or the person who’s making the work. And so I think that’s what I was trying to set out to do again this time—specifically, about how we perceive time, and how much either appears or doesn’t appear based on how you’re talking or thinking about it. And, you know, “time is money” is a very obvious one. It’s very familiar. That part of the book when I’m talking about that phrase in particular, I kind of imaginatively set that chapter at the Oakland port, because if you think about what shipping containers are like, right? Like a shipping container is a standardized box. It was standardized for very specific reasons, right? To be, to make commerce go faster and to be interchangeable. And that’s a very specific form, and I think, for me, standing at the port looking at those containers and thinking about this idea, time is money, meditating on that and sort of like how not given that is—that is actually a very strange way to conceive of time. It’s the most familiar, but it’s also the most strange. And so I kind of really wanted to pursue that strangeness and help the reader and myself not take it for granted as much as I think we’re encouraged to.

EVYou also explore how language—describing how we tell time, even simply the use of “o’clock,” referring to “of the clock”—signals a supposed domination of clock time over the living world. And its ways of telling time imposing, as you write, “an abstract grid onto a decidedly diverse landscape,” which in turn contributed, along with many other factors, to the distancing of our relationship with the living world.

JOYeah, there was a really interesting moment that I was kind of looking for when I was reading. There’s a book by David Landes that’s about the history of timekeeping. And I was kind of digging around in that book looking for the moment when clock time separated off from natural cues. Because I think it’s important to note that humans have always been very attentive to time. They have to be, right? Like it’s very important, it’s always been important, right? So timing and being attentive to time that’s, you know, as old as we are. But the notion of time as stuff that is measurable, accountable, interchangeable, that is measured in hours and minutes that don’t have anything necessarily to do with when they’re happening or where they’re happening. You know, time zones would be another example of this. Like the time being uniform within a time zone. I found that there was this weird moment—it’s sort of fuzzy and it’s hard to define, but you know, a lot of people trace the clock time to a monastic context, right? Like a monastery that has those prayer times—canonical hours. But those hours—although there was starting to be that pattern—my understanding is that they were still affected by sunrise and sunset. So they were adjustable, basically. Like many things were adjustable at the time.

And then something happened, and it seems to have to do both with technology and sort of cultural needs: like on the one hand the escapement, which is like a part of a clock that can sort of keep the mechanism going as opposed to like a guy ringing a bell at a certain time, right? That happened. And then also towns that were becoming very commercial started needing to be able to count up and measure labor hours that they were buying from people. And so some confluence of those things led to this notion of an hour: like an hour that can just exist, you know, in the imagination. And that an hour is an hour, and a labor hour is a labor hour, and it sort of doesn’t matter what season it’s happening in, what time of day. And for me, that is a really crucial separating point. That is when this idea of time as stuff started to peel away from all the things that it had been embedded in previously.

EVWell, it also feels like this notion of belonging to time in a very unhealthy way. You know, it’s just inherent in “of the clock.” You say it and it’s like, well time owns me, time is money. I’m owned by this unit of value that is imposed upon me and calculated. When you think about it, it’s quite overwhelming.

JOYeah. It was upsetting to do that kind of research, because what I found was that at the very root of this now sort of everyday prosaic way of thinking about time was the idea of buying and selling other people’s time. You can’t separate the history of timekeeping, and even time zones, from both colonialism—which involves also putting people to work right—and industrialism. But it’s always an interesting question throughout history to ask, who is timing whom? Timekeeping doesn’t just advance itself, right? We don’t have more and more minute measurements of productivity for no reason. It’s like there was always a reason to be doing it, and the reason was always to get more work out of people faster.

EVYeah. And you spent a lot of time diving into the implications of [the foundation] this historical setting laid for, as you said, industrialization and colonization and modernization and the kind of technical revolution that has even further imprisoned us in these units of time.

JOYeah, yeah. And you know, it’s funny, ’cause on the one hand it’s upsetting; on the other hand, I have sort of started to see it as just one language for time among many. And as a tool, clock time allows us to coordinate our actions, right? It is like the lingua franca, right? It’s the measurement that everyone understands. So as a tool, sometimes you have to use it, obviously. But I think the part that’s sort of more distressing is how much it’s— Even for me, right? Like even as I was writing the book, I was really coming up against the sort of difficulty of not taking that to be time itself. Like if you tell someone “time is not hours and minutes,” you’re gonna get a lot of resistance—but it’s not, you know? It just goes to show that there’s this one sort of historically specific way of reckoning time that got, I think, really deeply embedded. Not just in how we think about what time is, but also things like worth and what work is, and you know, all that kind of stuff.

EVIn the intro to the book, you wrote something that I really resonated with: “As planet-bound animals, we live inside shortening and lengthening days; inside the weather, where certain flowers and scents come back, at least for now, to visit a year-older self. Sometimes time is not money but these things instead.” That gets to what you were just saying.

JOYeah. And I think later on I quote Barbara Adam—who’s a sociologist who inspired a lot of my work in the book—sort of making a similar point, where she, after having delineated what standardized time and sort of economic time is like, goes on to say that in reality, I think she says, complexity reigns supreme—which I just, I love that phrase. But she’s like, yeah, we’re humans and we live on a planet and there’s also social time and memory and all of these things that are not so linear and standardized. And even though it’s true that one of these ways of thinking about time has cultural dominance, it’s also not true that it has total dominance. And I find there to be something very hopeful about the fact that, actually, we do retain the ability to speak these other languages of time. And, also, all you have to do is hang out with a three-year-old to have a different way of thinking about time.

EVYou, you also talk about how learning to speak a different language about time would help bring climate justice and self-care together into the same effort. Not two topics you hear paired together very often: self-care and climate justice. And I wonder if you could unpack this and speak to how a different language about time would help facilitate this coming together.

JOSo that was something that I think I’d sort of been grappling with for a while—related notions are in How to Do Nothing, right? Like the self and the larger context and the grief and how to sort of be in the world as a concerned and sensitive person. But that really came into focus for me in the event that I mentioned in the introduction of the book, in the way it was titled, which was “Is There Time for Self-Care in a Climate Emergency?” And Minna Salami, who is a great author and was one of the people on the panel, in her response to that prompt basically said, that is an unanswerable question because it’s sort of imagining, I think the way she put it was like stealing little bits of time for the self, you know, while this catastrophe is going on and seeing those two things is kind of unrelated—which is why it’s so hard to think about that question.

Her comments were some of the first things that helped me start to think about if you have these two different feelings that seem really unrelated: I, the individual today, don’t have enough time; I’m running out of time; I never have enough time; I have this really antagonistic relationship to the clock and the calendar. That’s one feeling. And then you have the other feeling, which is: I’m at the end of time, right? Like I might be at the end of time, and everything that I am worrying about right now may be rendered completely irrelevant tomorrow. And also, just the grief, right? That’s about things that have already happened. So there’s that, and I think what her comments helped me see was that if you sort of dig down from both of those feelings which feel unrelated, you will kind of come to a common root. And the common root is the way that time is spoken and thought about, and the way that time is specifically talked about in the context of extraction. You know, “time is money” being one of them, but also, historically, the fact that, for example, colonists who would show up in a new area would see everything there, including the people living there, as being outside of time, outside of historical time, as if they’re sort of automata. And that is the mindset behind extraction, and it still is, right? That that part of the world is inert and it doesn’t exist in time with us. It’s sort of like this toxic language of time that has in different ways led to, now, these feelings that feel irreconcilable. But once you see what they have in common, you can see that actually you won’t be able to address either one without addressing that common root.

Which is why, for her, addressing that root is both. So, thinking about time differently, for her, is both addressing climate change and what we would call self-care, I think of it as just care, right? Because the other thing is that, I think about the phrase “self-help” a lot, obviously, because my work is sometimes shoehorned into that category. And it’s interesting to me that if you take a less individualistic view of the self, like you recognize that you live in a network of support—you’re giving and getting support all the time, from people you do and don’t know, that’s true, and then it’s also very true as we know that we are extremely embedded and inextricable from the nonhuman world, so there’s that connection as well—then the phrase “self-help” doesn’t make any sense. Self-help would just have to be help, or the way I think of it, as either readjusting or rebuilding relationships between different people in things and places, right? So when I think about it that way, I actually have no problem with the idea of self-help, because I don’t think of it as self-help. Obviously help is needed, otherwise people wouldn’t be seeking it out. People are in pain, and they’re uncomfortable, and they’re worried, like they should be. But if you sort of let go of that individualistic notion that’s behind sort of commercial self-help, that question, “Is there time for self-care in a climate emergency?” no longer makes sense.

EVRight. Because in order to respond to the climate emergency, one has to seek help and that has to be through relationship, and just a simple turning of the way we think about it opens up so many possibilities for deepening how we relate to the world around us.

JOYeah, I mean I think a lot about habitat restoration. In Alameda we have the nesting grounds, it’s an artificial nesting grounds for the least tern. It’s man-made, right? And I think about how obviously that’s helpful to the birds in that case or habitat restoration is helpful to the ecosystem, but it’s also obviously helpful to the people doing it. The people doing it are experiencing a sense of meaning and connection that is missing from most, I feel like most people’s lives right now. And so I think that’s like sort of an easy example of when you think less about self-help as improving one’s life in a sort of material or instant way and rather about seeking meaning and connection again, that sort of supposed dichotomy between climate crisis and self-help kind of falls away.

EVOne of the ideas you return to throughout the book is the difference between chronos time and kairos time, whose simple definition you could perhaps describe as quantitative time and qualitative time. And you write that the difference between perceiving chronos and kairos may begin in the conceptual realm, but it doesn’t end there. It directly affects what seems possible in every moment of your life. And that it also affects whether we see the world and its inhabitants as living or dead alive. Can you talk about this?

JOYeah, I think that distinction between those two ancient Greek words, chronos and kairos, that’s something that’s been helpful to a lot of people who have been thinking about climate specifically, because they’re two very different ways of seeing time. If I had to describe them for myself personally, chronos is like everyday, calendar time. Or I’ve been thinking about this lately because of all the storms that we’ve had here in California: chronos is like the time that gets interrupted by something like a storm, right? Like when the storm’s not happening, you’re just sort of going about your life, and your biggest question is how can I get to the next week and get through my to-do list? And that’s chronos to me. And then kairos is like the interruption, the big thing that happens that you remember years later. Whether that’s, I mean I have many friends who’ve had children in the last couple years. So like having a child, or you know, whether it’s good or bad, like a storm arriving and totally interrupting your life. And sometimes it can be very subtle. I know for me, I’ve had experiences where I read a book and I get to the end and I’m sort of like, I need to go sit on a park bench and rethink my entire life. You know? But like basically these are moments of action, moments of change. Sometimes I think of them as like earthquakes. I live very close to a fault. You live very close to a fault, you know. But there’s a moment where sort of things happen, and it’s very dynamic.

EVYou step off that conveyor belt. Like you step off that conveyor belt of chronos time and you’re in a different world.

JOYeah, yeah, yeah. Exactly. And I think the reason that really matters to me is that chronos for me is where nihilism and determinism live. So if I’m thinking about that sort of abstract plotting towards the future kind of time, it’s much easier for me to think that the future is a foregone conclusion. That there isn’t anything new that’s going to happen. There isn’t anything new that I’m gonna do. And there aren’t really a lot of healthy responses to that, right? Like one is, well, I’m just gonna live out my little life in the shadow of disaster. That’s not a happy feeling, right? Or there’s like, I am just gonna be permanently freaked out all the time and sort of, you know, feel like what is the point of anything, right? To me, these are not sustainable ways of thinking about the future.

And then for me, kairos is this reminder of the kind of inherent unpredictability and creativity of every moment. When you look, especially, at history, right? I’ve spent a lot of time looking at archives going very far back, but just considering these moments in which someone in the past also didn’t know what was gonna happen and was also responding to their moment; and the way that history eventually gets written, it sort of obscures that, right? It feels like everything that happened was supposed to happen. But everything that happened was not supposed to happen. It’s actually not that hard. You just have to look at like one or two things. It’s kind of that sense that you have when you look at a colorized historical photo, from the thirties, and you’re like, oh yeah, those were just people. Like, that guy could have been my friend, you know, down the street. This moment was alive.

And so, unsticking the past from that sort of chronos way of thinking, to me, it makes the future look very different. Obviously, it’s not true that anything could happen in the future, especially with climate, right? There are things that we know. But it makes the future look a little more like a field of possibility. And if the future is a field of possibility, then I now have choices and I now can do something that either I didn’t expect, or no one expected. And I think that’s so important right now because I feel like the way choice is presented to us right now is often as consumers. Buy green, for example, right? Like, which green product are you gonna buy? That’s the choice that’s given to you. It’s not what are you gonna do, it’s what are you gonna buy? What kind of lifestyle are you gonna have? And it feels so undignified to me; it feels like a dropdown menu. Like, this is the only choice I get? And after a while, living in chronos time and living in that dropdown menu kind of way—it can get in your head, and it can make you forget that you do actually have these choices that are not on the menu that you haven’t even thought of yet. You sort of need to put your heads together with some other folks and sort of make a trail where there wasn’t one before.

EVYou also spoke about how being trapped in chronos time set the stage for the climate crisis and the racial injustices of today, and that it played a role in turning people and the more-than-human world into resources.

JOYeah. I think a really interesting mental exercise to do with anything or anyone is to think about whether they have been afforded experience, the ability to experience, which means like having a past and a future. So one of the most fascinating things that I came across in researching the book, that I talk about somewhere in the middle of the book, is a study about the lesser minds bias. It’s not something you would immediately think has to do with time, but it’s a bias that other people, especially people in out-groups—so people you don’t identify with—don’t have as rich of an emotional inner life as you do. And so in this study that I referenced, the people running the study ask the participants to think about houseless people and show that the part of their mind that has to do with theory of mind, and imagining that someone has an inner life, is not lighting up when they’re thinking about these people. And then they ask them the question, what kind of vegetable do you think they would like, this person? Just imagine that and then suddenly it is lighting up, right? And my interpretation of that in the book was, well, someone who wants something and has desire must have a past and must have hopes for the future. For something to have desire, it has to exist in time. And so it’s almost like—that participant who’s thinking about them—it’s almost like this person has entered a time with them. Like this person is now also an actor. This person has wants and needs and regrets. And I think that kind of flipping is a really helpful and interesting way to think about why we do or don’t afford that to, you know, the nonhuman world, and also many groups within the human world—like out-groups, as they were talking about in the study. And it is that relegating of part of life to the realm of the timeless—like it might be cyclical, but it’s considered timeless—that is so much at the root of the logic of extracting it. It’s lifeless. But it’s the same mechanism that’s behind dehumanizing someone, because you’re seeing a person as almost like an instance. To go back to people without housing, it’s interesting that people don’t think about how someone might go in and out of housing within their life. You know, what led to that? What might be in their future? They’re just sort of seen as they’re just there. And so I think that’s an example of what happens when you take something out of time, or it doesn’t seem to inhabit time in the same way you do.

EVYou wrote that the book itself was “written in kairos for kairos—for a vanishing window in which the time is ripe.” What’s it like to write in kairos for kairos?

JOIntense. I mean I wrote the proposal before the pandemic started, and so I was not expecting to be writing at a time when a lot of the ideas that I had planned on researching and writing about were going to become so vivid. As one example, I was, I think at the beginning of the pandemic I was writing the chapter about labor time, and I was thinking a lot about wage labor and sort of compensation and how different people’s time is valued. And then there was the whole conversation about essential work going on at that time. And also just the kind of visual contrast of people working from home, like myself, and then this whole other segment of people whose lives had not slowed down—they actually sped up, like if they were working in health care or delivery or anything like that. So these things became very, almost like sharpened in a way that I think was probably helpful, but it was definitely intense.

I often have this feeling like I’m falling asleep and waking up and falling asleep and waking up, over and over again, or like remembering and forgetting something and remembering something and forgetting something. And when I feel like I’ve woken up and I remember something, it’s always, this is the time; there’s all this other stuff that’s distracting me, but there are the things that are the most important to me in my life and I want to be a part of this historical moment of responding to this crisis. And then it seems so clear to me in those moments and then it gets obscured or fogged over for a while, and then it comes back, you know? And so, I feel like writing this book was like a really long period of time in which I did feel like I was able to grasp onto that feeling of urgency but also clarity.

EVAnother area you return to frequently in the book is the difference between horizontal and vertical time, which does share some parallels between chronos and kairos, but is also very different. Could you talk about the difference between horizontal and vertical time and the importance of embracing the different dimensions of vertical time which you explore?

JOYeah, so that distinction is something that I got from Josef Pieper, who was a German Catholic philosopher who wrote Leisure: The Basis of Culture. That was a really important book for me early on. So, he describes horizontal time in a way that would actually include what most of us, I think, would think of as leisure. So, for him, horizontal time is work, and then it’s refreshment for work. I think of it as like work and the weekend, like the weekend in which you’re recovering so that you can go back to work and be refreshed. And obviously that’s all centered around work; not to say that you’re not enjoying that weekend. So, he describes that, and then he says, the point of leisure should not be to work better. Leisure should be experienced for its own sake. Like he’s sort of trying to move the center of gravity away from work and towards what he is defining as leisure. And so, work and refreshment for work—that’s horizontal.

And then, the way he describes vertical time reminds me of the way you would feel if you were looking at a really incredible view or a sunset, or I don’t know, a baby—like the things that remind you of your mortality and the sort of fragility of your life, but also this deep sort of awe and gratitude about the fact that you exist at all. And he describes it as sort of cutting through that horizontal plane; it feels in that moment almost like it invalidates the horizontal time, like work, and refreshment for work, are extremely far from your mind in those moments. It’s easy to imagine it as like something you experience standing on top of a mountain or something. But in the book, I mentioned that I have experienced it waiting in line at the grocery store before. Like I think it’s definitely easier to experience that feeling in certain situations and contexts, but I think all it really requires is a kind of, any kind of, interruption—whatever that’s triggered by—in that horizontal plane. And so that’s his definition of leisure, and it seems, you know, he doesn’t—

EVIt’s also about transcendence, too, right? It seems like there’s a transcendent quality there.

JOOh yeah, definitely. And for him it’s spiritual. Yeah. And he doesn’t talk about ecology or anything like that in the book, but I think to anyone who cares about the nonhuman world, it’s very obvious that that’s kind of where that would live. I think a lot about when I used to work at Stanford and I would be walking to class, late. I had all these big bags ’cause I took public transportation from Oakland. So I was just on this whole like sort of journey, and I’m thinking about how I am late and I didn’t prepare enough. And the Stanford campus has an incredible number of birds because of where it is, and I would see a warbler, or just something very unexpected, and just freeze, almost like I forgot who I was in that moment; and in that moment I was also connected to a migratory clock in a migratory sort of geography, and also just this kind of extreme focus on something outside of myself that at the same time is reminding me that I am an animal, an earthly being. And then you know, that would collapse in on itself and I would go to class. But for me that is an example of that kind of interruption.

EVYou wrote this passage I really loved in response to vertical time: “What songs are audible when the wind stops? What has been kept alive in the time snatched from work and sheltered from ongoing destruction—what moments of recognition, what ways of relating, what other imagined worlds, what other selves? What other kinds of time?” It’s very beautiful.

JOThank you. Yeah, I also, I was on a show, a public radio show recently, and the host asked people to call in or write in with their own observations of this other kind of time. And they’re so beautiful. There was one where someone described, I think they had covid and so they were sort of like stuck inside, and they watched a single poppy growing. And I was like, that’s so beautiful, right? Like, I don’t know, it almost reminds me of an issue of frame rate. Like certain things are only visible, certain movements are only visible at a certain frame rate, and if you are only paying so much attention to something, and it’s really spread out, you will not be able to see it moving, or you won’t be able to see it changing.

EVRight, right. This winter in California—as you know ’cause you live here as well—has been a very wet and a very cold one, and it got me thinking a lot about the seasons and just how in flux they are at this time. Winter lasting longer, spring starting later, erratic stops and starts throughout this time confusing human and nonhuman alike. But also perhaps that within this disruption there’s an opportunity to return to a different and older way of thinking and living in relationship with the seasons. And you write about the seasons in the book and how “there is no inherent reason for a season to be any length of time, much less of four equal, mutually exclusive lengths. Until relatively recently the naming and recognition of seasons or seasonal entities was an indicator of some action to be taken: collecting, hunting, harvesting. Likewise, no element of a season can be considered in isolation from space, time, or other components.” Can you speak to this a bit?

JOYeah, yeah. So I grew up in the Bay Area, and for some reason, two notions that are very unintuitive, if you simply just look around in the Bay Area, I internalized: one was that of four seasons, there are four seasons; and then the other one was that the Bay Area doesn’t have those. So it’s like a double sort of impoverishment, right? It’s so different now, but I’m in my thirties. But I do seem to remember as a kid thinking like, oh yeah, we don’t have a real winter, we don’t have fall colors, right? Like we don’t have the caricatures of the seasons in the Bay Area. And when I was writing How to Do Nothing, I learned a lot more about bioregionalism, and so it meant that I became a lot more familiar with plants and the local ecosystem, which means becoming attentive to when they flower and sort of what they do.

I talk a lot about the California buckeye in this book and how it goes dormant in the late summer. It’s very unusual compared to other trees’ kind of schedule. So as I paid more attention it became clearer to me, Oh yeah, things are changing all the time. Sometimes they change faster than others, sometimes it’s more visible or sensible than others. But something is always happening. There’s always like some transition that’s about to happen. And once you know it, it’s very obvious, right? Like you live with those kinds of seasons. And I remember, before the pandemic, I was hiking in Huckleberry Botanic Preserve, which is a really lovely trail in the East Bay. And I saw some Douglas iris flowers, which I love, and they, to me, from my perspective, my calendar, they were early. And I remember I was like walking thinking about that, and then I was like, what’s early?

The Douglas iris does not have a calendar. And then I was thinking, what is time to the Douglas iris? It’s water and temperature and maybe sunlight, you know, and probably some other factors I don’t know about. But those were all present. And so for the Douglas iris, it is time; it is time to flower. And I think about the same thing with birds and nesting and all of the sort of messages and cues that they’re interpreting that are not the calendar. So I feel so fortunate that I live in a place where you can see those minute changes so easily. It just did not occur to me until yesterday: I’m really glad that my book came out in the spring, because like spring is a time where in most places things are changing visibly, right? The way I feel about seasons now is I either think about microseasons or I just don’t think about them at all. I just think about it as like, this is the time of year when this happens. And I cite examples in the book of Indigenous Australian names for our seasons where it literally just means like the time when the X plant flowers. That’s the name of the “season.”

EVYeah. And there’s, you know, seventy-two seasons in Japan. And there are six seasons in Melbourne. And there are places around the world that acknowledge the larger seasonality and changes that we go through. But yeah, I’ve been thinking about that a lot myself, because it’s such a rapidly changing environment. What happened last year is going to be different than this year because of all the climate change–related factors. And it only pushes us to be more aware of what happens in the present. You know, it’s not to me a negative, only, that spring’s season, as it was twenty years ago, is changed, because it makes us realize that we are actually not the dominant imposing factors. And yet we are at the same time. I mean it’s a paradox, but it’s interesting.

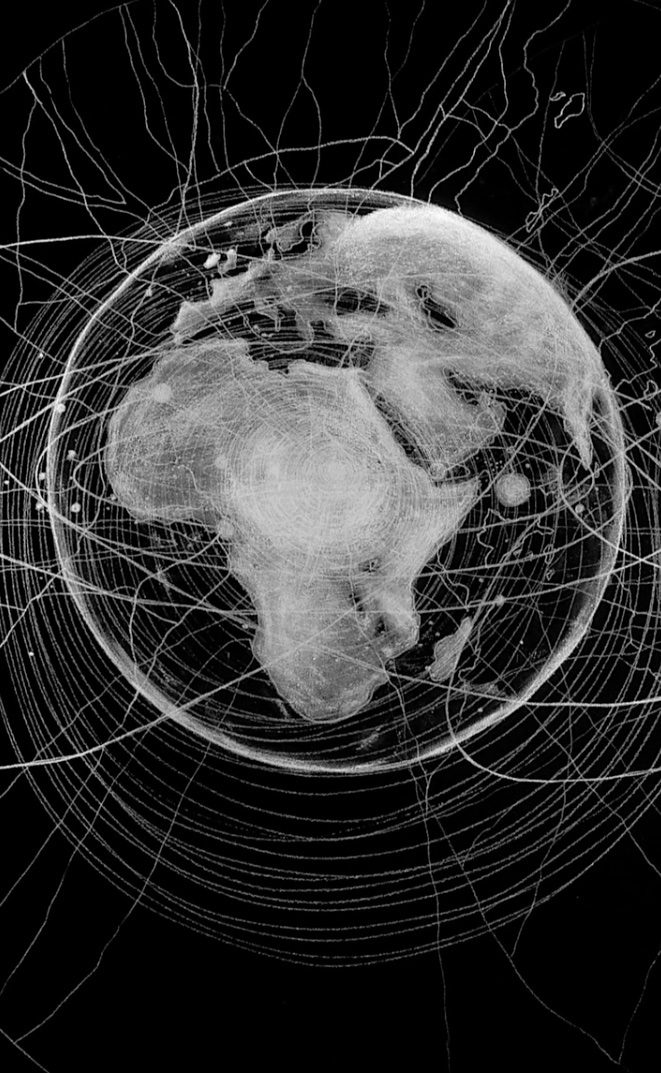

JOYeah, right. You know, the part of the book where I write about the fires in 2020: I describe adding, I think like a bookmark tab on my browser for air quality, and you know, how many people had really thought about air quality that much before, right? It was upsetting, right? Because the air quality was often really bad, and it was determining whether or not you could go outside and do things. But I also think that it made me think about air in a way that I maybe hadn’t, and on a very big scale. Like I describe looking at that website windy.com, which I find so mesmerizing, and windy.com is showing these kind of swirls and flows of air that can be quite large, you know—really small and really big at the same time. And suddenly air did not feel like this empty thing to me anymore. It’s like, this air came from somewhere else, it has stuff in it, it’s going somewhere from here, you know?

EVYeah. Yeah. There was a question you asked that was also in this section of the book, another one that stayed with me, which was, “What would happen to our view of time if we could better see our wheres?” Which is a really simple question but also a very, very complex and profound one: “if we could better see our wheres.” Can you talk about that?

JOI think that question I am either quoting or referencing the Indigenous scholar Daniel Wildcat, who is one of many that I think is trying to articulate this inseparability of space and time, right? That in itself is like a big mind trip. Like when did those separate? And you know, that’s a very similar history to time being money. But, if you look at something like, you know, that chapter is set in Pescadero. If you’re on a rocky beach and you look around and you look at the rocks and you think about geology, it becomes very clear that time and space are inseparable. Like the identity of a rock is what happened to it. Like if you look up what is serpentine or what is sandstone, it’s just gonna tell you what happened to that material to make it be serpentine or sandstone.

So there is that sort of like basic inseparability that I think is again one of those things that can seem very different but on the other hand, I think, is quite intuitive for us if we think about it, or just kind of look around at the material in the natural world. And yeah, I think the same way that time has become abstracted and thought about as stuff—the idea of a man hour or labor hour, you know—the same way that is actually quite unnatural is the same way that I think about the notion of space: so like the idea of square footage for example, or real estate, in particular like investment, like buying a bunch of land as an investment. The land, other than its resources—say like water—doesn’t necessarily have an identity oftentimes in those kinds of transactions or ways of seeing it. Whereas I—and this is something that I really appreciated from Daniel Wildcat—I really believe that every place has a personality—I think he uses that word also, “personality”—and has an identity. And there is no place that is equal with another place. And obviously in the everyday world—

You know, I grew up in Cupertino. I complain a lot in How to Do Nothing about the sort of identical conglomerations of businesses in these horrible shopping centers where you do feel like it’s all the same. But on an ecological level, no place is the same. I really love when you’re in a place that’s kind of on the boundary—boundaries can be very small or very large, right?—but when you start seeing a new type of tree, for example. Like you see one and you see two and then you see a lot more, and then suddenly you’re in an area that has a lot of Douglas fir, or something like that. Just thinking about that difference across all of space. And I think that not only did the concepts of abstract space and abstract time arise together historically, I think it’s also a really helpful way for us to kind of get back to a different way of thinking about time where, if abstract time and abstract space are kind of like a Tron-type grid—like just a grid, a featureless grid, stretching into infinity—then the opposite of that would be for me thinking about moments in time as being as different from each other as points in space are different from each other. When I think about time, I think almost of hills and valleys and like big dunes and thinking about time that way, whereas like the reality is that like time is those dunes. So it’s not a metaphor. But for me, in sort of thinking about it, it’s been helpful to kind of use both time and space to try to move away from that abstract placeless, timeless, featureless, identityless way of thinking about something.

EVI mean that leads towards something I’ve been thinking about a lot myself lately, which is the materialization of time. And in the book you tell the story of a branch on a tree you visited regularly in a park near your home, and how your observations of this branch led you to the importance of unfreezing something in time and seeing the materialization of time itself. Can you talk about this exercise and observation and where it led you?

JOYeah, that was something that I think I started doing somewhat incidentally, because it was during the pandemic, so I was going on the same walks over and over again. And I had paid attention to that little sort of section of buckeye trees before, but I thought it would be an interesting experiment to really, like really, narrow my focus to a very specific part of one specific tree and sort of see what that allowed me to notice. I mean, you should see my camera roll. I have like hundreds and hundreds of photos of this branch, and it’s actually incredible. I’ve known about buckeye trees for a long time. They’re on the Stanford campus, so I would see them— I would have described myself as familiar with buckeye trees before this, but as a result of looking at this one branch, I became extremely familiar with the kind of really specific events that would happen in one branch. Like when the bud that’s been there all winter, sort of dormant, would start to turn green and it would start to get bigger. And then it opens, and then a separate set of leaves comes out of that. And then those open and they get bigger and then they turn kind of less waxy. As of right now, the flower buds have come out, but it hasn’t fully grown yet. Then those will open, then there’s going to be this amazing smell. I now know what an individual flower on one of those flower stalks looks like. Like what are the different components of that. It’s kind of the same feeling that you would get if you were doing a drawing observation that really forced you to sit and look at the different components of this and how they’re changing.

And then obviously those flowers wither. And then it was really interesting for me to see, even as the leaves are dying and the tree is going dormant, the yellow of the leaf—like the way it spreads across the leaf or the way it spreads across the tree—is very non-uniform. So even that as an expression of time is really interesting. And then it goes dormant, right? And the fact that it goes dormant for so long makes the next year, when it opens up again, so incredible. It’s sort of like, oh, this whole time you had this secret, right, that this is gonna happen. And yeah, I refer to that as unfreezing something in time, because to me the opposite way of looking at a buckeye tree would be as a static entity. The way I think of it is like—I don’t know, this is a weird comparison—the way products look on Amazon before you’ve bought them. It’s just like an object, or it’s like a thing and it doesn’t have a past or a future and it’s not alive, right? And obviously most people know that trees are alive, but what does “alive” mean for someone. Does it mean it’s green, and it has roots; or does it mean it’s actively changing and reacting to conditions around it every single second? And so unfreezing something in time to me is using that focus on a specific point or feature to help make something’s aliveness more accessible to you.

EVYou wrote about the distinction between “seeing the tree as evidence of time and seeing it as symbolic of time”; that “the literal tree … is encoding time and change at this literal moment”; that “a story is being written there,” and a story is, of course, alive.

JOYeah. Right. I felt like I had to make that distinction, because trees are a really good metaphors for time, right? If you think about, you know—my boyfriend and I were just talking about this yesterday—as you get older, or as something progresses and decisions are made, those would be like the big branches at the bottom, right? Then you have the smaller and smaller decisions that are always constrained by the last ones. Like that’s a very interesting metaphor, but because it’s an interesting metaphor, I had to distinguish, you know—in the book I was like, no, I’m actually talking about— I’m not talking about metaphorical tree, I’m talking about the tree that’s in front of you. That everything about it is based on things that happened in the past. Like it is a materialization of time.

EVYeah. Yeah. I mean this also leads into the importance of recognizing patterns of time, which you devote time to in the book—patterns that exist all around us—and that if we begin to recognize these patterns, worlds open up to us, the inanimate becomes animate, and an invitation to step into a relationship of kinship with the living world arises. It’s like there’s a deepening from the observation you describe, as you start to see these patterns, and then through that, it’s almost like a door is swung wide open that says, “Hey, there’s a world here. Engage with me.”

JOYeah, totally. I mean, something that I still think about a lot—and I have a photo of it in the book—is tafoni, which I don’t know, is there tafoni near you? Like on the coast? Have you seen it?

EVI don’t— I’m not sure.

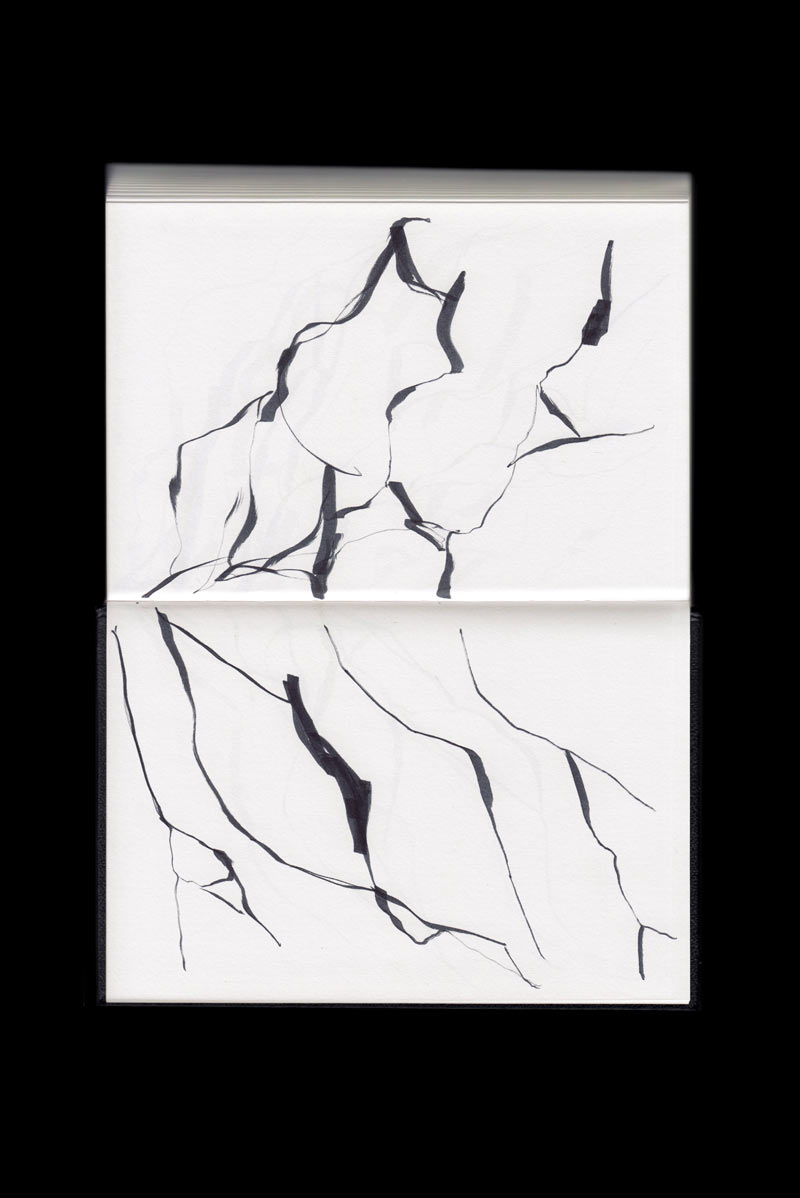

JOOkay. So tafoni is a pattern that you will observe in rocks. It’s very common. I’ve seen it a lot near Mendocino, like up north. And then I’ve also seen it at Pescadero, and I have a photo of that in the book, but it’s like this pattern that you’ll see on sandstone boulders or cliffs that almost makes it look like a sponge. So it’s sort of like a series of different shapes and different sized holes clustered together. And it’s the kind of thing that, if you saw it and you looked at it for more than a couple seconds—it’s sort of confusing. Like why does this part of the rock look like Swiss cheese? And if you look it up on Wikipedia or something, or if you do like a cursory search, it’ll say that it’s “salt weathering.”

But then if you look a little bit further, it’ll say, it is salt weathering, but actually there’s some disagreement. You know, like, there’s something more here. And then I ultimately found this paper that someone had written all about tafoni. They basically said, okay, yes, it is salt weathering, it involves salt—the salt is like getting deposited on the rock and it’s kind of working its way in—but basically the way the pattern looks will depend on the salt, but also the composition of the rock in any particular place, and also things like the air, and all the conditions around the rock, and this sort of long list of things. And basically, he’s implying that there’s no way to explain a particular pattern of tafoni without knowing everything that happened in that place.

And so in the book I compare tafoni to experience, like the idea of experience. Like a person is who they are because of what happened to them and what they remember and who they started out as, right? Like all of these sort of factors. And the only way to explain one’s current identity is to take all of that into account. The tafoni is important to me because it’s a rock. And I think people don’t think of rocks as being alive, and they certainly don’t relate to rocks and think of rocks as having a memory or personality. And for me, knowing that about tafoni is like, when I see it, I really do imagine that that is the rock’s experience, just like my experience.

EVThat also leads to this notion of each of these patterns—they’re each full of agency, they each are deserving of respect. And you talk about this and how seeing these patterns in this complex way, each influencing the other, it also leads to an abandoning of hierarchy.

JOYeah. Right? There’s a study that I cite (near the tafoni) about Indigenous Mexican children being interviewed about what things are alive. And some of them give the definition that we would be more used to, like something’s alive if it reproduces and eats and all that stuff. But then when some of them are asked, Is the ground in the dwelling alive? they say yes. And they ask why, and [the children] say, because of the animals. And then the researchers are like, What if we take away the animals? Is it still alive? And they say, yes, for the plants. And as they discuss in that paper, that answer is exhibiting a very different notion of aliveness, in which to be alive is just sort of to create effects in the world.

And again, that’s one of those things that feels unintuitive. But I find that when you really try to get to the distinction between something that—using our sort of traditional definition of aliveness, what is and isn’t alive—like, for me, I think about a tree root that’s going into some rock, and you think of the tree as alive and the rock as not. But if you really go to the interface of the tree and the rock and you think about the minerals or just all the interactions between the tree and the rock, it becomes much harder to think of the rock as not being alive. You know, I think anyone who spent any time thinking about ecology has an appreciation for how all of these different elements are pushing on each other all the time, all in one kind of big process that includes us. So, so yeah, it does kind of do away with that sense of hierarchy, because you sort of understand that these processes are cascading into other processes, and it involves everything and everyone. And to me, like if I had to answer the question, what is time? Like, that to me is time. It’s just that kind of total process.

EVYou wrote about how “the co-creation events of our lives do not play out in an external, homogenous time,” but rather “they are the stuff of time itself”; that you are in “constant conversation” with an alive, animate world, like you’re just mentioning. And that “when you remember this, the future can cease to look like an abstract horizon toward which your abstract ego plods in its lonely container of a body.” Instead, “it” returns a dynamic exchange with the animate world always speaking to you. And that “the task for many of us is to learn once more how to hear”—that once we’ve shifted our perception of time, we need to change the way we listen. Can you talk about this a bit?

JOYeah, I mean, I think maybe it’s helpful context to know that—and this is something that I didn’t really realize until after I finished the book. I think that a lot of my work, both in this book and the last one, has been motivated by a reaction to the feeling of alienation. So it’s kind of like that dropdown menu feeling I was describing before, right? There is for me a deep loneliness in the way a lot of modern life feels in terms of how we’re able to relate to other people and how we’re able to relate to the nonhuman world. And there’s a part of Braiding Sweetgrass, where Robin Wall Kimmerer is describing—I think she’s talking about like what it would feel like to not know the names of the things that are living around you. And then she says, I imagine it must feel like showing up in a city and you can’t read any of the signs, right? Like, that’s a deeply frightening and lonely experience to have. I likewise feel like I don’t wanna live my life in a way where I’m just kind of here and I consume things and I have certain achievements and then like I go away. That’s like, when I think about it that way, I always, I always imagine myself as like this little speck that’s sort of orbiting around the Earth, but never really touching down. And I really don’t want that. And so I’m always kind of trying to work against that. I remember I had this experience a couple months ago or so, I was driving to a place in the Santa Cruz Mountains that I really love and I have a long connection with just going back even to childhood. And I was really worried about how it was gonna look because one of the storms had just happened, I think, and then as I was sort of thinking about climate change and how different it was gonna look and how worried I was about that.

And at first I thought, I’m worried about this place becoming unrecognizable to me. But then a few moments later I was like, that’s not what I’m worried about. I’m worried that this place will no longer speak to me. That’s what I’m actually worried about. And that could happen either because it’s rendered unrecognizable and destroyed, or it could happen if I’m no longer able to hear it. Or both of those things could happen. And so I feel like I need that personally. And I mean, I don’t wanna presume, but I think a lot of people need that kind of feeling of hearing and being heard, by not just people, but by the places that they’re in.

EVYou know, patterns lead to rhythms, and you write about rhythms of time and how they can take on many meanings and you ask, would it be possible not to save time, but to garden it by saving, by inventing, stewarding different rhythms of life and I really love this and this idea of gardening time, it really stuck with me. Can you talk about this notion of gardening time and working hand in hand with the rhythms of life present there?

JOSo, you know, thinking about something like the microseasons, even just different times of the day, I think that there’s something really potentially inspiring about that difference, right? Like celebrating that difference and making use of it. The idea of there being like a good time to do different kinds of things and that that’s not an inconvenience, that’s actually something to be enjoyed and celebrated. There was something actually really ironic that happened when I was writing the book at the very beginning. You know, I had two years to write it. This is so ironic. I wrote out a schedule for myself that was very uniform and sort of imagined that I was gonna work at this very constant rate, and I was gonna hit these milestones in these equal intervals of time, making no allowances for the fact that obviously there are different stages of researching and writing.

Also, I’m not going to be the same person a year from the beginning than when I started. I will know more. Things will go faster at a certain point. I will hit a rough spot, they will go slower, you know? And I just like wasn’t taking any of that into account, and I started missing all of my own deadlines. And I was sort of worried, like, oh no, I’m not gonna make it. And then at some point in the middle I was like, oh, this is just not, this is just not how writing happened. You know? I was like applying industrial time to myself, right? And so I think a lot of times just logically it makes more sense to sort of organize things with some kind of attentiveness to the reality of change. And that most things involve stages, and those stages are different.

But then I think you can move beyond that to really celebrating that and really enjoying that. I think a lot about seasonal festivals. I love that we still have seasonal festivals. Like up in Northern California, I think they have a marbled godwit festival, which I’ve always wanted to go to, but it’s just celebrating the marbled godwits. Like that’s it, right? And that’s such a seasonal thing. It’s like, oh, they’re here, you know, and then they’re gonna be gone. And that’s what gives that experience meaning when you look at them—Oh, they’re here and then they’re not gonna be here. And isn’t it a miracle that they’ve arrived again? Right? So kind of just celebrating that difference that’s already inherent in how things are happening. And I think that that can allow us to find more meaning in each one of those different stages in any process.

EVYou also wrote about how social time, our social time, is inseparable from the rhythms of the Earth, and that if time can be gardened, then it’s also possible to imagine its increase in ways other than individual hoarding.

JOYeah. That is something that’s really stuck with me, actually, after having finished the book. I find it to be a very interesting sort of thought experiment to do. I mean, this is assuming that you have some amount of latitude and control over your time, but I find that like, if you get into this sort of mindset of where your brow is furrowed and you’re like, I’m not being productive enough, and you have that hoarding feeling about time, you know, like, I don’t have enough time and I’m not accomplishing what I want to accomplish. I have found that sometimes in those moments to do something that feels like giving time away is actually what I need, and it feels backwards. But, because the truth is, if time is not money, there isn’t anything to give away. Right? Like, you’re just making a connection with someone else. That’s what’s happening. But it turns out that that’s usually what I have needed that whole time.

And so I’ve been thinking a lot about this feeling of generosity in time. I mean, I talk about in the book, as a metaphor, those beans that my friends grew. She started growing them twenty years ago and couldn’t find them at the store anymore, but her friends that she’d given them to grew some of them to maturity and gave them back to her, and now she has them and she can still give them to other people, right? So it’s that sort of non-zero-sum game way of thinking about time and value, like, you can actually do something that’s good for both people. Like, just because I give something to you, like time, doesn’t mean I have less.

And so I think that has been something that I’m excited to actually bring more of into my work, because I have this document on my computer that is titled Work Log. Again, I realize that’s probably ironic, but it has a list of everything that I did for the book starting the day that I started writing or started researching it. And even if that was like, I didn’t “do” anything but I had some kind of realization, I would put that on there. And I was thinking about how for the next project I linguistically would like to frame it in terms of things that were given to me. So instead of, I did this and this and this, “my friend gave me a really important book.” This actually happened last week—my friend gave me a really important book that I recognize is going to be crucial for my next project. Or like, “so and so told me about this,” or, you know, “this bird landed in a tree near me and it made me think about this.” Right? But just kind of like moving the focus away from me and the idea of work and just recognizing that both How to Do Nothing and Saving Time I consider to be—not that I didn’t work—but I consider them to be the sum of many, many gifts that were given to me over time by many different people, and by places, specifically.

EVJenny, it’s been a really lovely speaking with you today. Thank you so much for taking, I guess, time—to throw that in there—to chat about all this.

JOIt’s my pleasure. Thank you.