Paul Adams is the head of Photography at Brigham Young University. His current area of research focuses on alternative photographic processes and digital technologies. He is the recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship and his photographs have been featured in the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., the Royal Photographic Society, the Moscow International Foto Awards, the London International Creative Competition, and the International Kontinent awards in Izmir, Turkey.

Jordan Layton is a photographer and artist currently living in Los Angeles. He received his Bachelors of Fine Arts from Brigham Young University in 2017. His work focuses on self-exploration of cultural and religious identity. His work has been featured in publications and museums including Communication Arts and the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian in D.C.

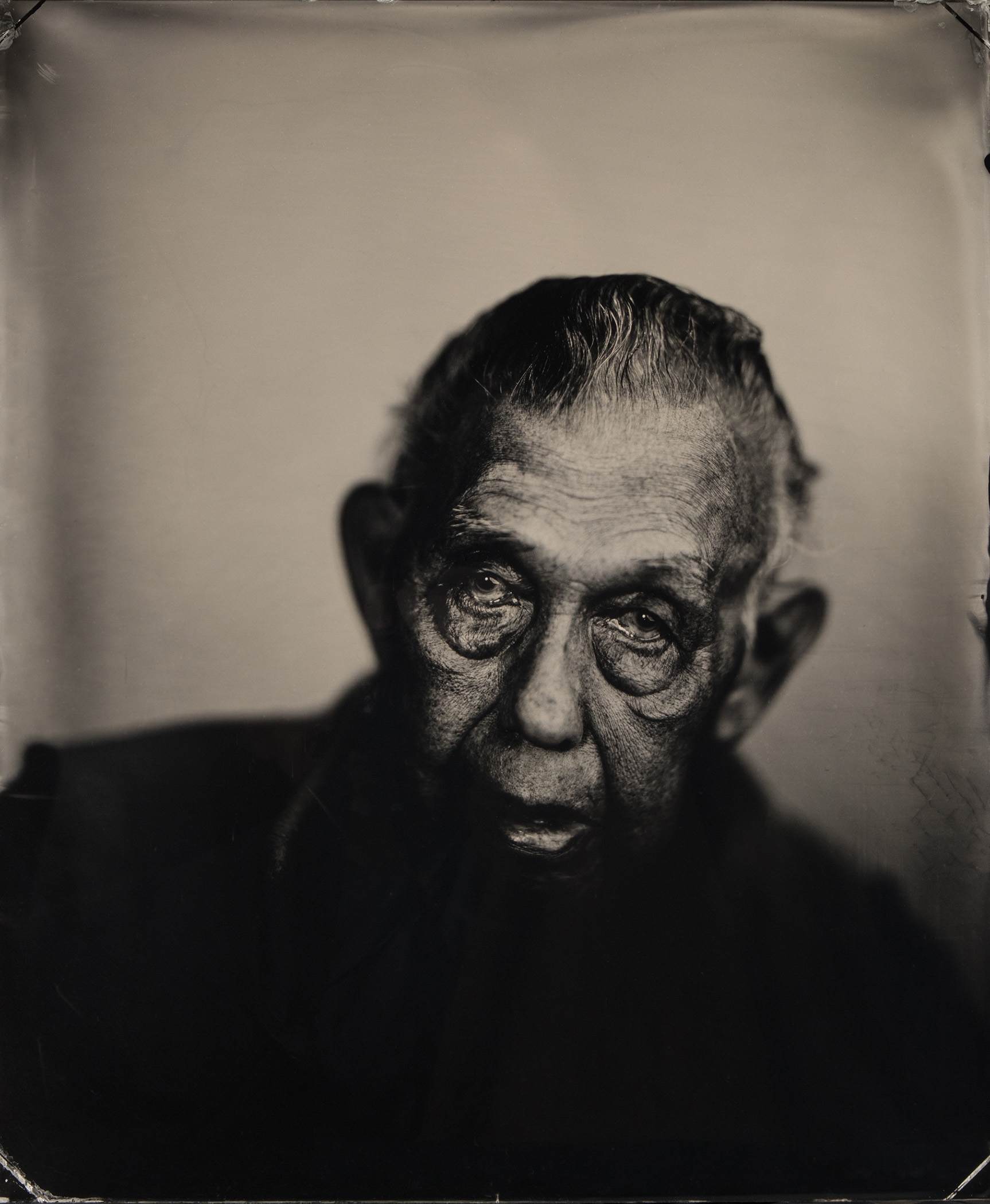

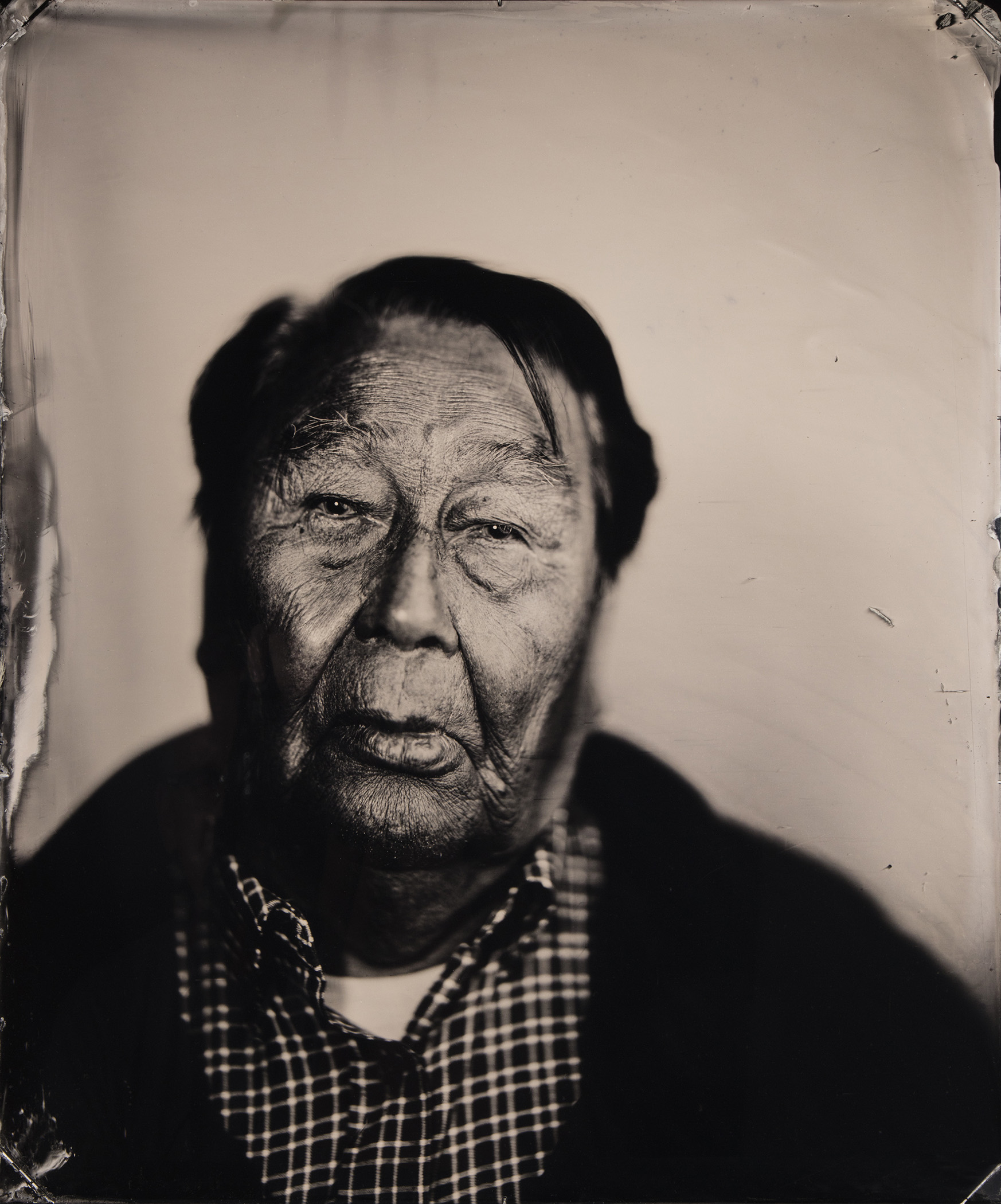

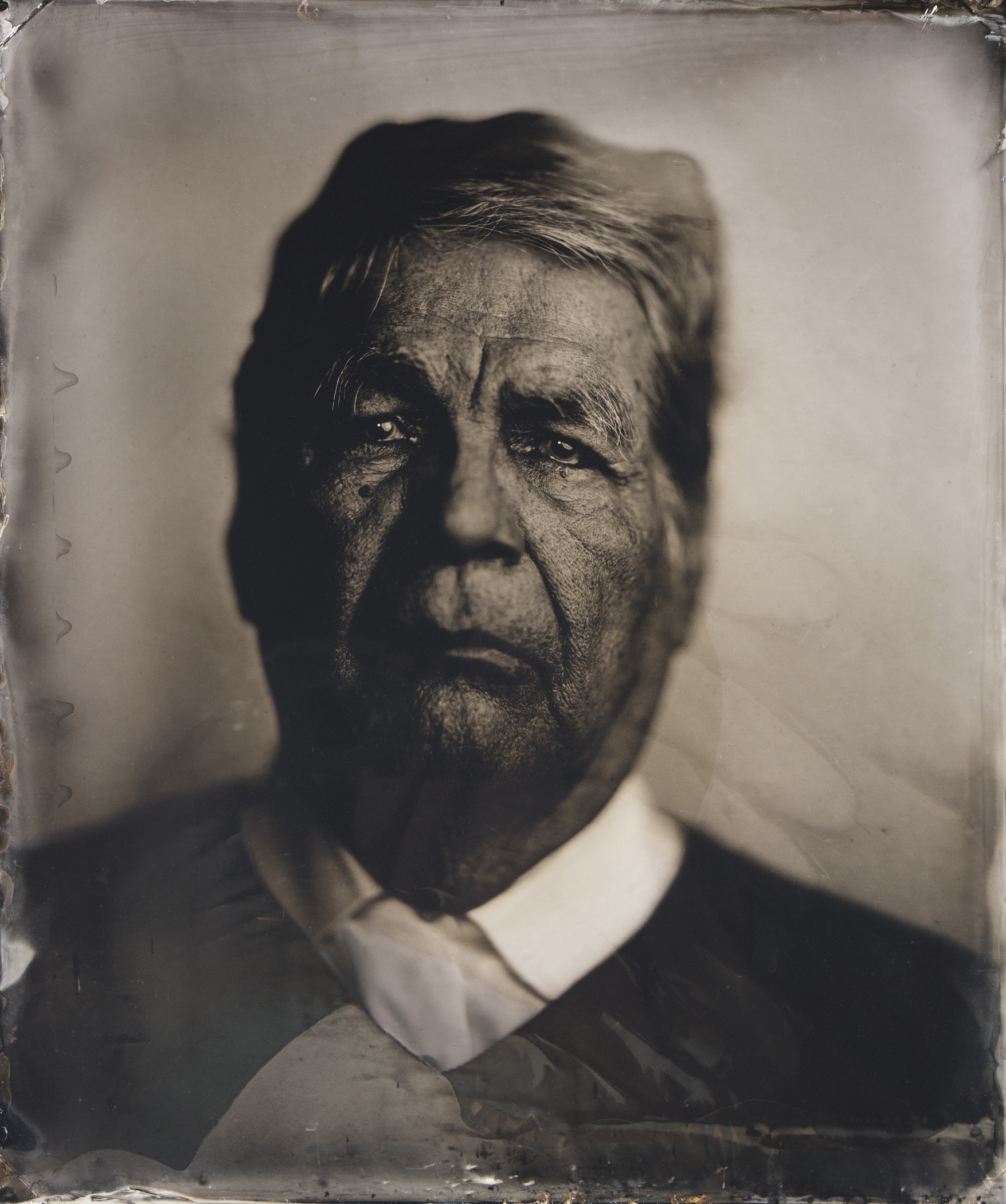

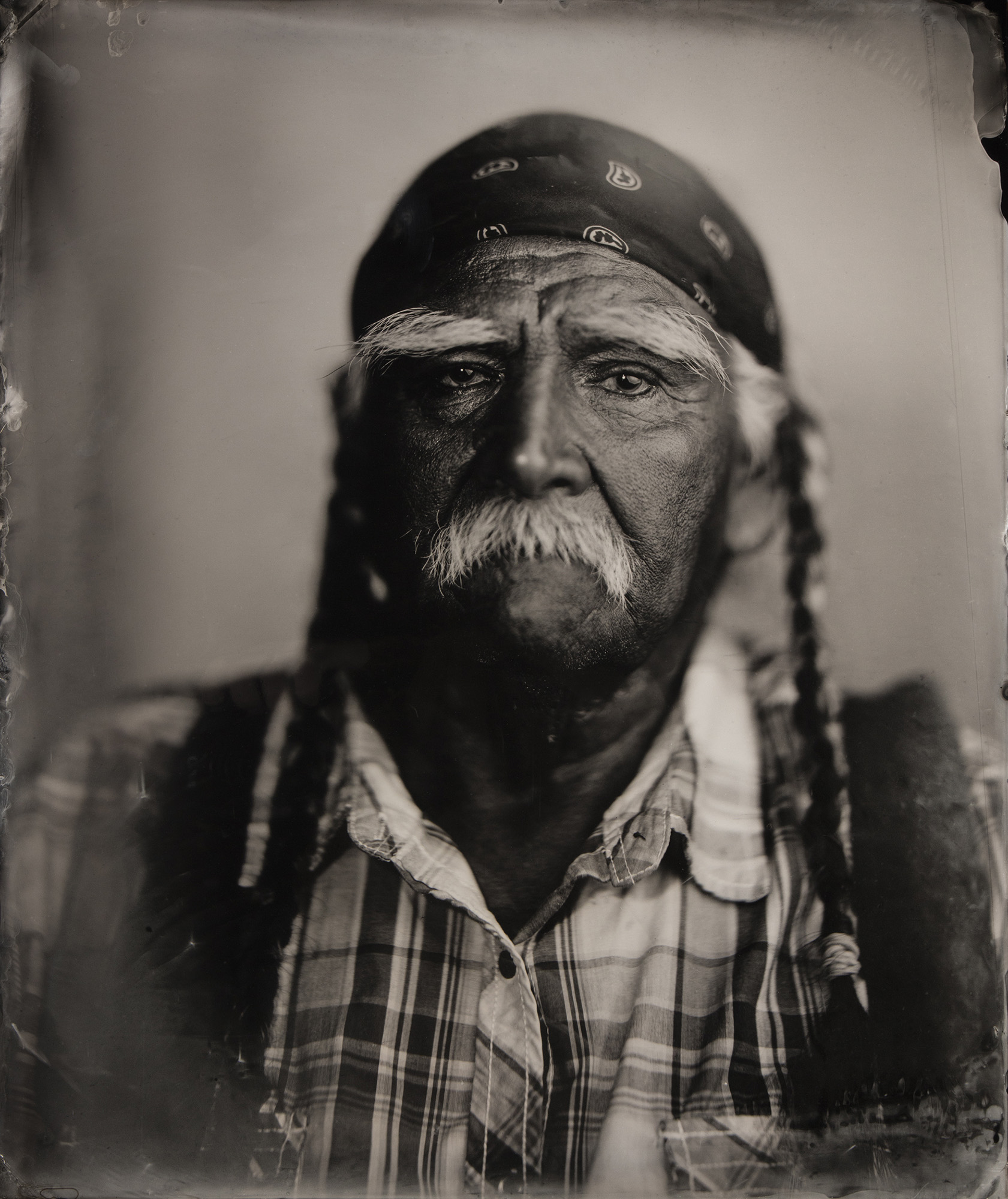

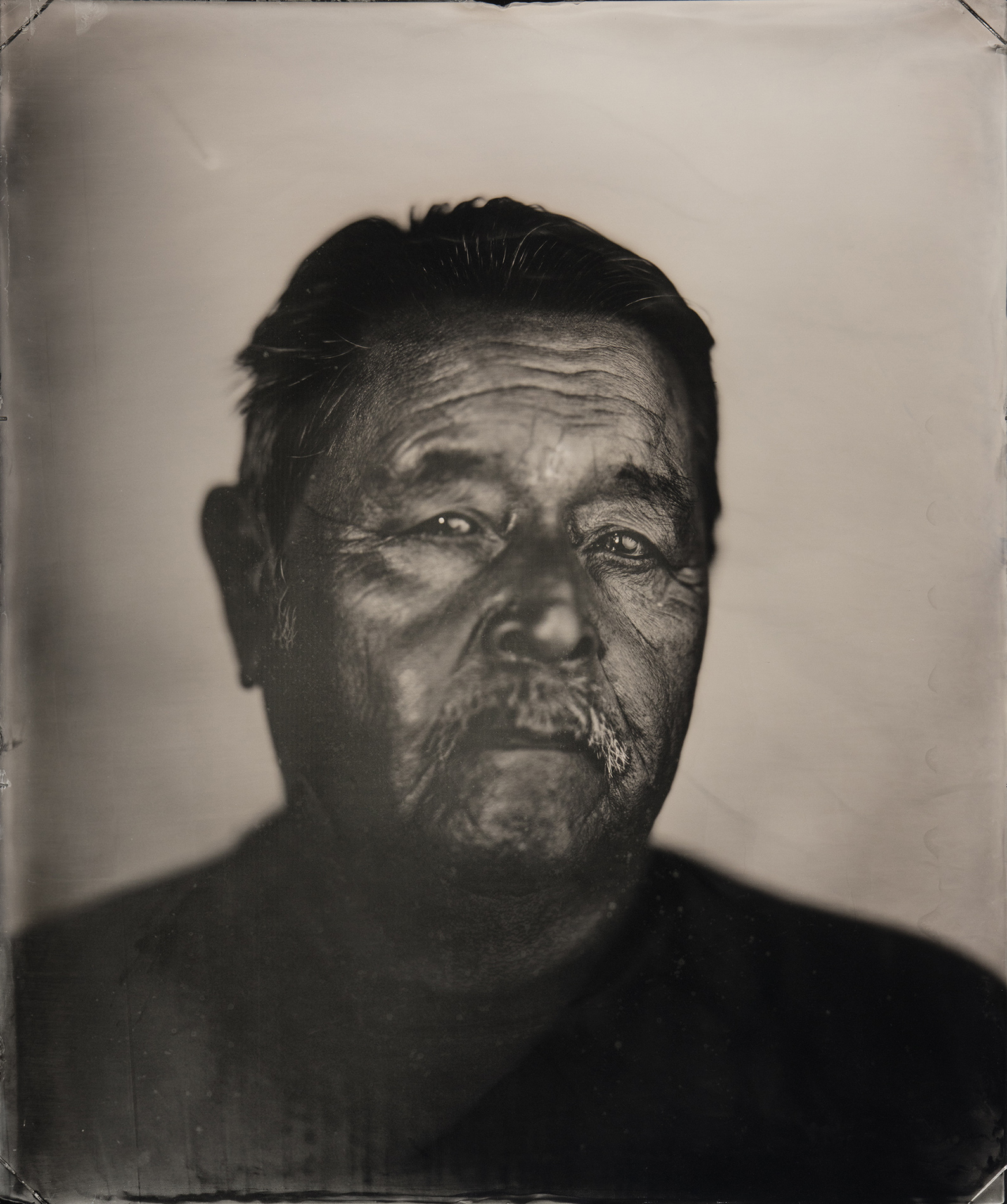

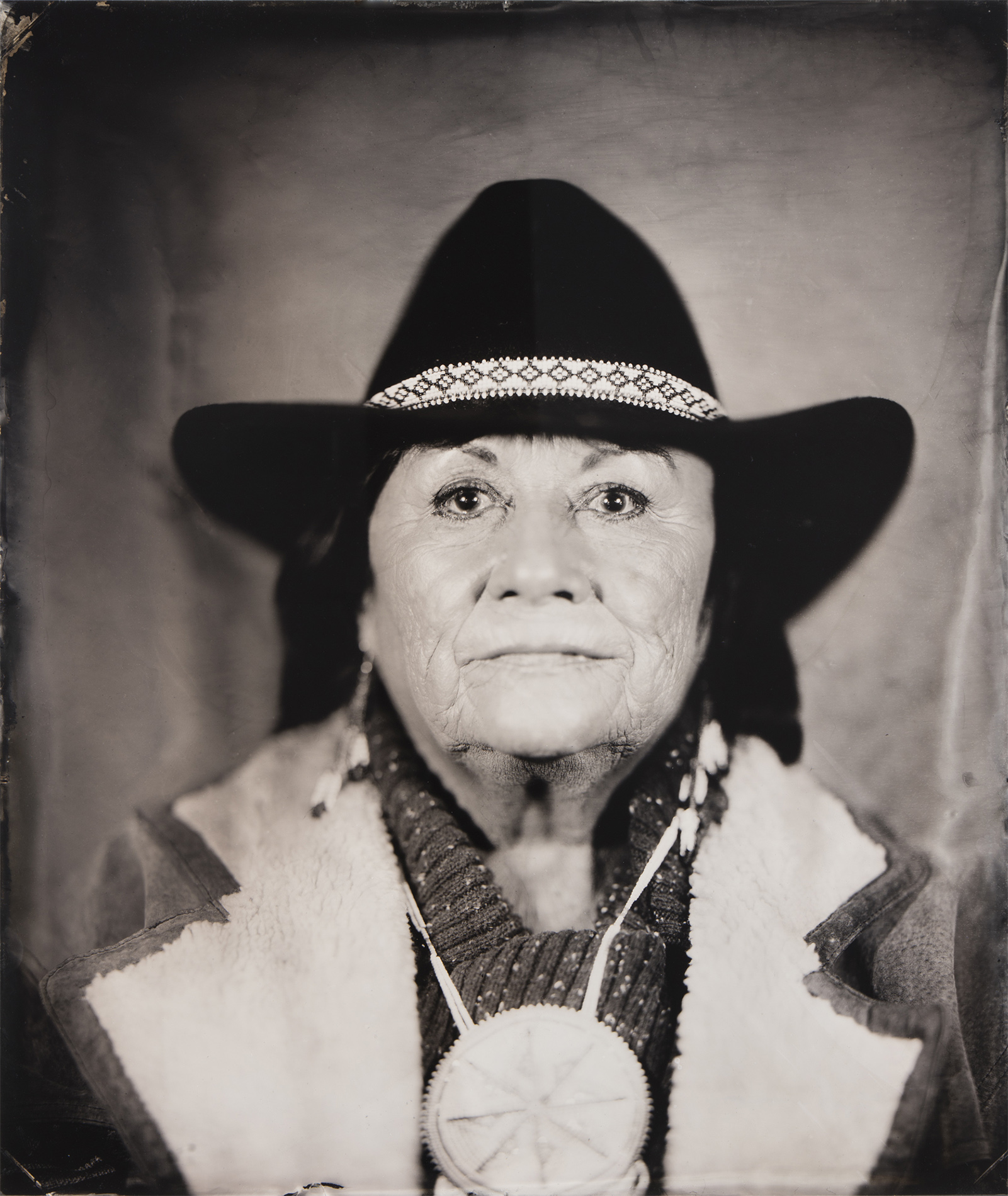

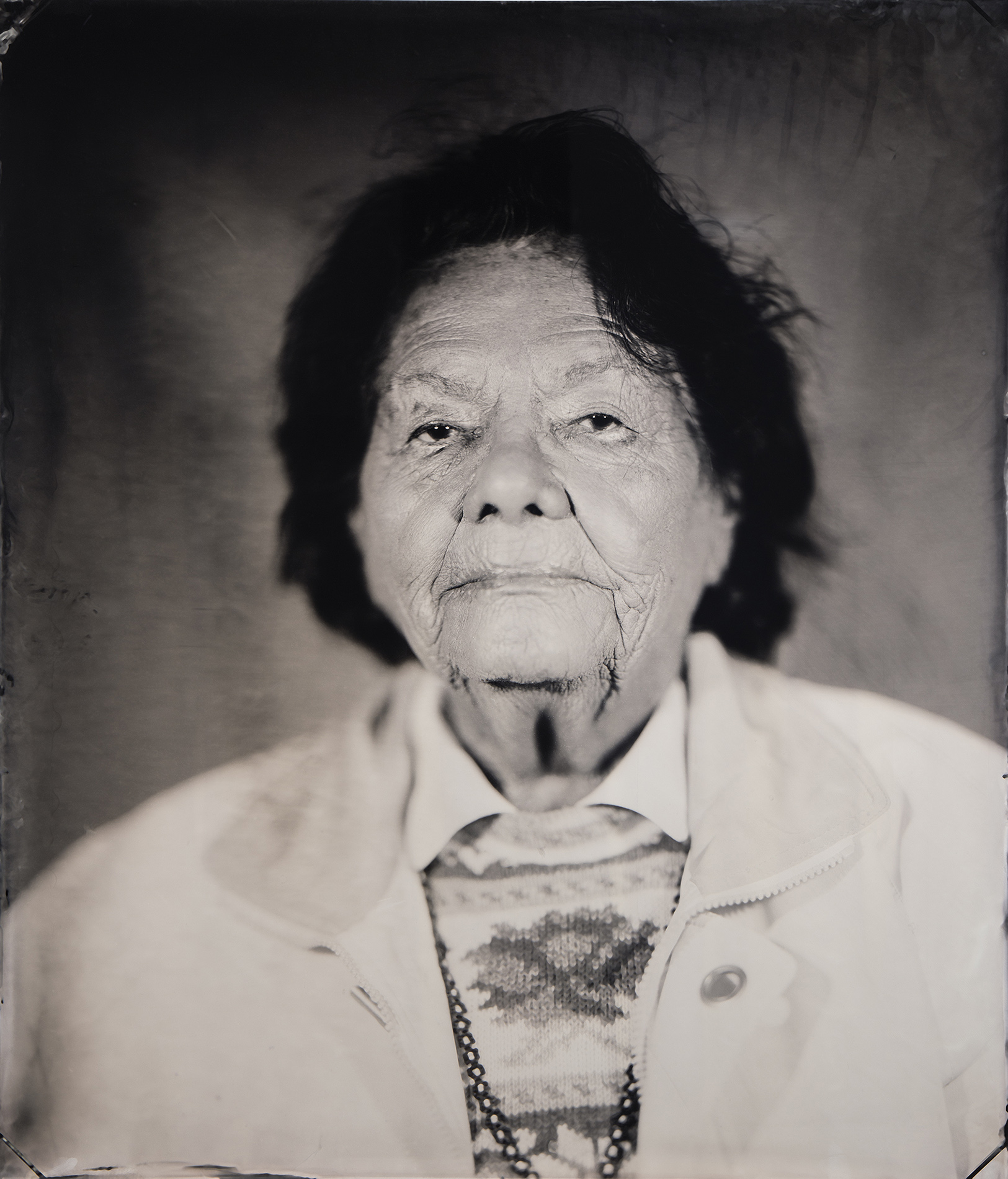

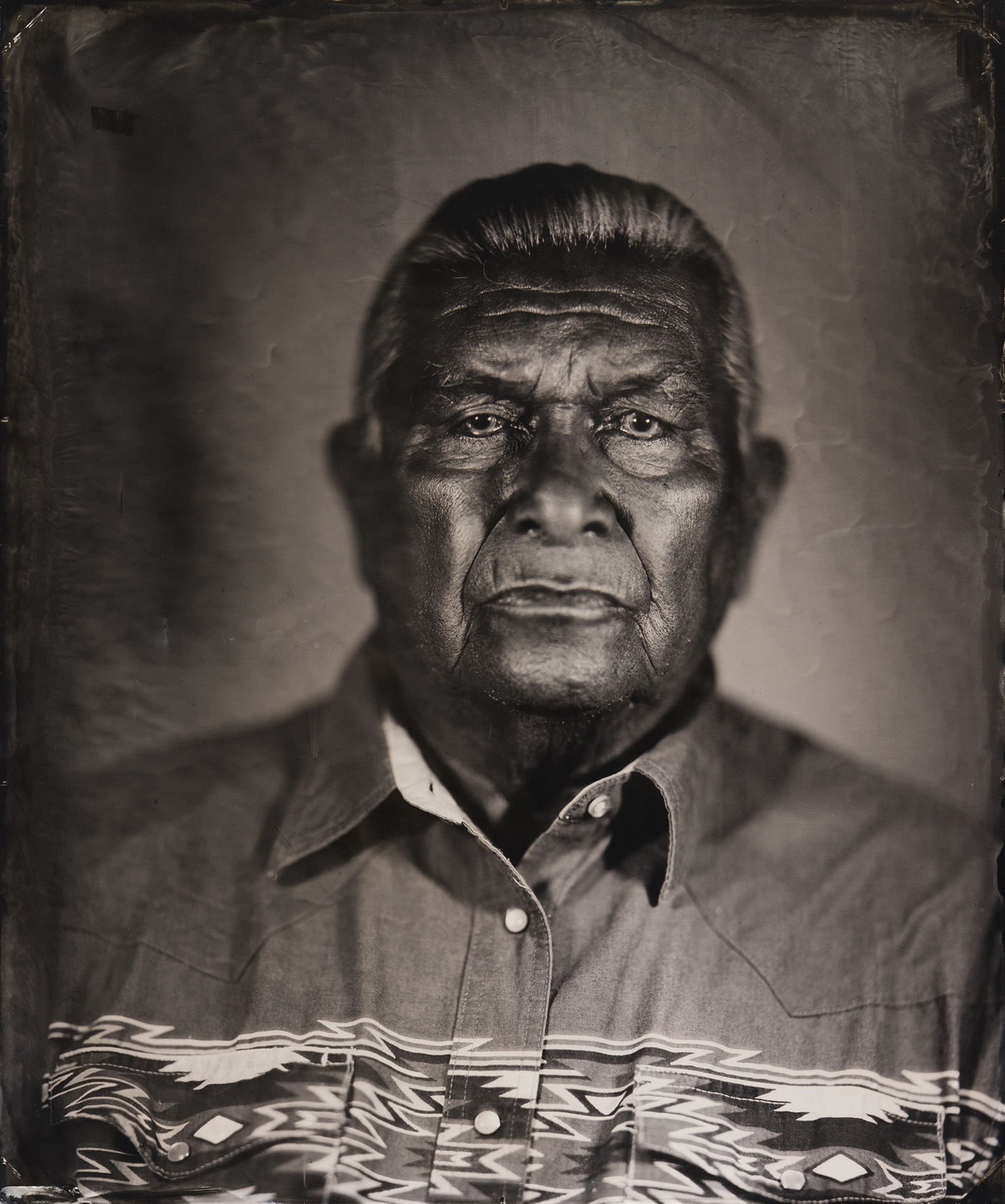

This series features tintype photographs of the remaining speakers of endangered languages in North America, highlighting the critical state of Indigenous language loss and celebrating the Native speakers whose voices embody resilience and revitalization.

Sally Carlough

Alutiiq

Kaguyak, AK

Nick Alokli

Alutiiq

Alitak, AK

Kodiak, AK

Mary Haakanson

Alutiiq

Old Harbor, AK

Florence Pestrikoff

Alutiiq

Akhiok, AK

Phillip Sabon

Ahtna

Copper Center, AK

Mammie Oxereok

Inupiaq

Ambler, AK

Joseph G. Norris

Hul’q’umi’num’, Halalt

Duncan, British Columbia

Duncan, British Columbia

Norbert Sylvester

Hul’q’umi’num’, Cowichan

Duncan, British Columbia

Arvid Charlie

Hul’q’umi’num’, Cowichan

Duncan, British Columbia

Alberta, Canada

Priscilla W. Eswonia

Mojave

Parker, AZ

Johnny Hill

Chemehuevi

Parker, AZ

Mojave Desert, CA

Rena Killian

Mono

North Fork, CA

Gertrude

Mono

North Fork, CA

Marie Wilcox

Wukchumni

Woodlake, CA

West Mojave, CA

Lucille Girado Hicks

Kawaiisu

Montclaire, CA

Luther Girado

Kawaiisu

Tehachapi, CA

Around the world, one language dies every fourteen days. By the next century, it is predicted that nearly half of the roughly seven thousand languages spoken on Earth will disappear, as dominant languages such as English, Mandarin, and Spanish exert their influence in an increasingly homogenized linguistic era, in which technology and world commerce push regionalized languages towards extinction.

In North America alone there are more than 280 vulnerable and endangered languages spoken within Indigenous communities. Fluent speakers of these languages are often over seventy years old. Who are these language keepers of North America? What is lost when their language goes silent?

The purpose of this series is to honor and share the work of the remaining fluent speakers of North American languages. In these photographs, each language keeper portrayed represents the gravity of all that is at stake when a language becomes endangered, as well as resiliency and the hope of revitalization.

This series features Marie Wilcox, the last known fluent speaker of Wukchumni; Gertrude Killian, one of the last known speakers of Northern Mono; Mammie Oxereok, one of the remaining speakers of Inupiaq; Florence Pestrikoff, one of the few remaining first-language speakers of Alutiiq; and Lucille Hicks and her brother Luther Girado, speakers of the Kawaiisu language. Luther passed away in February 2021, four years after his portrait was taken, leaving Lucille as the sole fluent speaker of Kawaiisu.

These portraits are created using a Civil War–era photographic process called a tintype, or wet-plate collodion positive. This unique photographic process creates a tin photograph that perfectly portrays the singular nature of the people being photographed. The light reflected from the subject is embedded in silver on the tin plate in the camera—thus, the photographic plate on display is a record of the actual light reflected from the subject herself.

This process is labor intensive and involves hand coating each metal plate with silver and exposing it to light. It takes a team of at least four people working together to create each portrait and requires hauling a six-by-twelve-foot cargo trailer—converted into a mobile darkroom—to each subject’s location.

But by far the most important and critical part of the process was building trust and relationships with the subjects and their communities. Too often, white voices have sought to control and co-opt the story of Native people in our country. We were honored and humbled to be invited into the homes of the keepers of these languages. As we sat with them throughout the lengthy process of creating the photographs, we had an opportunity to hear their stories and learn more about their roles as Elders. After seeing her tintype photograph, Lucille Hicks said, “The event of this process, to me as a Native Elder, is very emotional. It’s emotional in a good way. It takes my mind back to where I come from, who I am, and that I really am proud of who I am as a Native American.”

Within many of these communities, fluent speakers are participating in language revitalization efforts, seeking to pass their languages on to the next generation. Marie Wilcox created the first Wukchumni dictionary and is working with four generations of her family to keep the language alive. Luther Girado’s daughter, Julie, spent thousands of hours recording her father and aunt speaking the Kawaiisu language, creating an archive from which anyone could learn Kawaiisu.

This project celebrates the men and women who continue to speak their Native languages. It seeks to impart to viewers both the extent of Indigenous language loss in our country and the sense of possibility that can be seen in the light reflected back to us from these speakers.