HERE THEY ARE, Coyote’s twin daughters, Answer Woman and Question Woman, sitting on a fence rail high atop Sonoma Mountain telling stories. Some people say they are a pair of crows; others claim they are two identical looking women with long, dark hair. In any event, they have been on the mountain a long time. They are Coyote’s daughters, after all. The Coast Miwok people tell us that Coyote created the world and the first humans on top of Sonoma Mountain. They know that the mountain is a sacred place and that if you hear the twin sisters telling stories, you should listen. This is their predicament: Answer Woman knows all the answers but she cannot think of them unless she is asked. Question Woman, on the other hand, cannot remember a single answer, not one story, and she must always ask her question in order to hear the answer again.

This morning, stopped on the mountain, I overheard the sisters squawking, bickering, which was what caught my attention. Question Woman was upset that the stories her sister was telling were not Creation stories, not the stories from that time before people when all the animals were still human.

“You keep telling stories about the Forgetters,” complained Question Woman. “They are the people who left this mountain long ago, and when they came back to this land, they’d forgotten all the important stories. They didn’t even remember the mountain.”

“But Sister, nothing has changed,” answered Answer Woman.

“How can you say that? The Forgetters are foolish. They go about hurting one another. They hurt the animals and plants. They forget that we are one family. They forget that this world is our home. They know no limits. Even the Coast Miwok people, who settled closest to this mountain after Creation, even many of them have forgotten.”

“Which is why I tell stories about the Forgetters, so that we, all of us, remember. Those ancient people who lived at the time Coyote created the earth and people, they forgot; they too often acted foolish. That is what I mean when I say nothing has changed. We need stories to remember, just as those ancient ones did. The people today, spread out in the towns and valleys—we are one family. These stories, like the old stories, mark the land so that we can know the stories and find ourselves. Just as an outcropping of rocks on the mountain reminds us of a story, or a patch of clover alongside a freeway, even an old house in Santa Rosa. We share the same sky, the same sun and moon.”

“You made your point. I guess I’d forgotten.”

The sisters were quiet then. The day was warm. A cool breeze blew from the ocean that could be seen in the distance. The sisters, perched on the fence, took in the wide view of the valley, its cities and towns spreading out below the mountain. The sun rose higher in the sky. The air was pure. It was morning yet.

“No one creature or plant or rock on this earth can do everything,” said Answer Woman. “We need each other—that’s what the Forgetters forget. Which reminds me of a story.”

“What story?”

“It’s about a woman who has many gifts, the woman who met an owl, a rattlesnake, and a hummingbird in Santa Rosa.”

“What about her?”

“Listen.”

BELOW THE HILLS east of Santa Rosa there was a village called Kobe·cha. In the Southern Pomo language kobe is rock; cha is house. The village sat on a knoll above a deep blue pond. It was a good place to live. Fish, bluegill and catfish, in the pond, plenty of acorns and deer in the hills. What distinguished the village was its triad of enormous rocks, connected one to another atop the knoll. Passersby on the plain, farther west, might see plumes of fire smoke, then look only to find these rocks and the villagers scurrying about below them, small as rabbits or birds. “Kobe·cha,” they’d say. Rock House. A small creek snaking below the hills fed the pond. Sometimes, with heavy rains, the creek swelled and the pond rose until the knoll was an island. But the villagers didn’t worry. Until there was another great flood, when the ocean itself would rise again, Kobe·cha would not be covered by water. “More rain, more grass for the deer and elk,” they said. An early American farmer dynamited one end of the pond, hoping to contain the winter rains. But it was a tract home developer who finally accomplished the deed, installing drains on street corners to catch the water.

It was around this time—say, the early 1950s—that Isabel was on the other side of town picking strawberries. It was May and it had been unusually hot for at least a week. Each second seemed endless, as if the sun had stopped time. Thick scarves covered the women’s heads, straw hats and sombreros for the men, but the heat found their backs and shoulders, baked their skin under their clothes, as they bent over the rows and rows of strawberries. Filipinos and Mexicans, poor whites, and Indians from different rancherias worked in the strawberry fields. Isabel was an Indian. She was twenty-five and plain, which meant she did nothing to call attention to herself. Anyone who talked about her might have claimed that her unwillingness to dress up after work each night or to cut her hair fashionably was the reason she still wasn’t married. Others might have said she was just quiet by nature and respectful. Still others might have said she was shy. Whatever the case, she minded her own business.

Sometime in the afternoon, as Isabel was filling her crate with fruit, a large ripe strawberry slipped away from her. Just as she was clasping it between her thumb and forefinger, it scurried under a green leaf as if it were a mouse or a lizard. She figured she was tired, the sun was too hot. Maybe she’d eaten too much for lunch or hadn’t had enough water. She straightened and took a deep breath. She wasn’t dizzy. When she reached for the berry a second time, again it escaped her. Again and again. And each time her fingers touched the fruit, it was gone, only to be discovered under yet another leaf. She went for water, splashing her face under an irrigation faucet at the edge of the field. When she returned, she picked the berries more quickly, pulling the crate along as she hurried down one row of plants and up the next, for she had no sense of how much time she’d lost and needed to make a daily quota for the farmer to pay her.

That night as folks gathered around fires telling stories and listening to the pockmarked-face Mexican with the silver moustache play his accordion, Isabel thought about what happened that afternoon and figured something had gotten in her eyes, temporarily blurring her vision, or that she had indeed been dehydrated. She dozed under the stars—no one slept inside the tents on account of the warm weather. She listened as the sound of voices and laughter blended with the melodic notes of the accordion. But all the while she saw that strawberry escaping her and felt the sensation of it slipping from her fingers. Soon it was day again. She was reaching for the strawberry. Drops of water glinted on the tops of her hands, and there was nothing else but the folks’ voices and the Mexican man’s music in the sky above her. But she was not asleep. She was wide awake.

The next morning, and throughout the day, she found she was alert, wide awake, despite the sun, which unbeknownst to her was even hotter than before. She bent over the strawberries, picking the red fruit, up one row and down the next. Only when the farmer arrived before lunch with metal barrels of fresh water did she realize how warm the morning had already been.

“I don’t want you to have to keep drinking that dirty slosh from the field faucet,” he said.

Isabel watched the men and women filling canteens and gallon glass jugs with water, then joined them lest she look like a sick animal left behind in an empty pasture. Up close, she saw the sun glistening on the water inside the glass jugs. She felt a strange attraction to the water, or maybe the reflected sun, she couldn’t tell which, but she was certain that whichever she reached for, the water or the reflection, it would escape her, slip from her hand, just as the strawberry had yesterday afternoon. She filled her canteen, though she truly wasn’t thirsty.

That night, wide awake, thinking of the strawberry and glistening water, she overheard someone mention Kobe·cha and the deep blue pond while telling a story, and right then, for no explicable reason, except perhaps to distract herself from the pictures that kept repeating themselves in her mind, she determined to find Kobe·cha, knowing full well that she would have to leave camp in the dark and return before daybreak, lest anyone notice she was gone or, worse, find her late for work and think she’d been out with a man someplace.

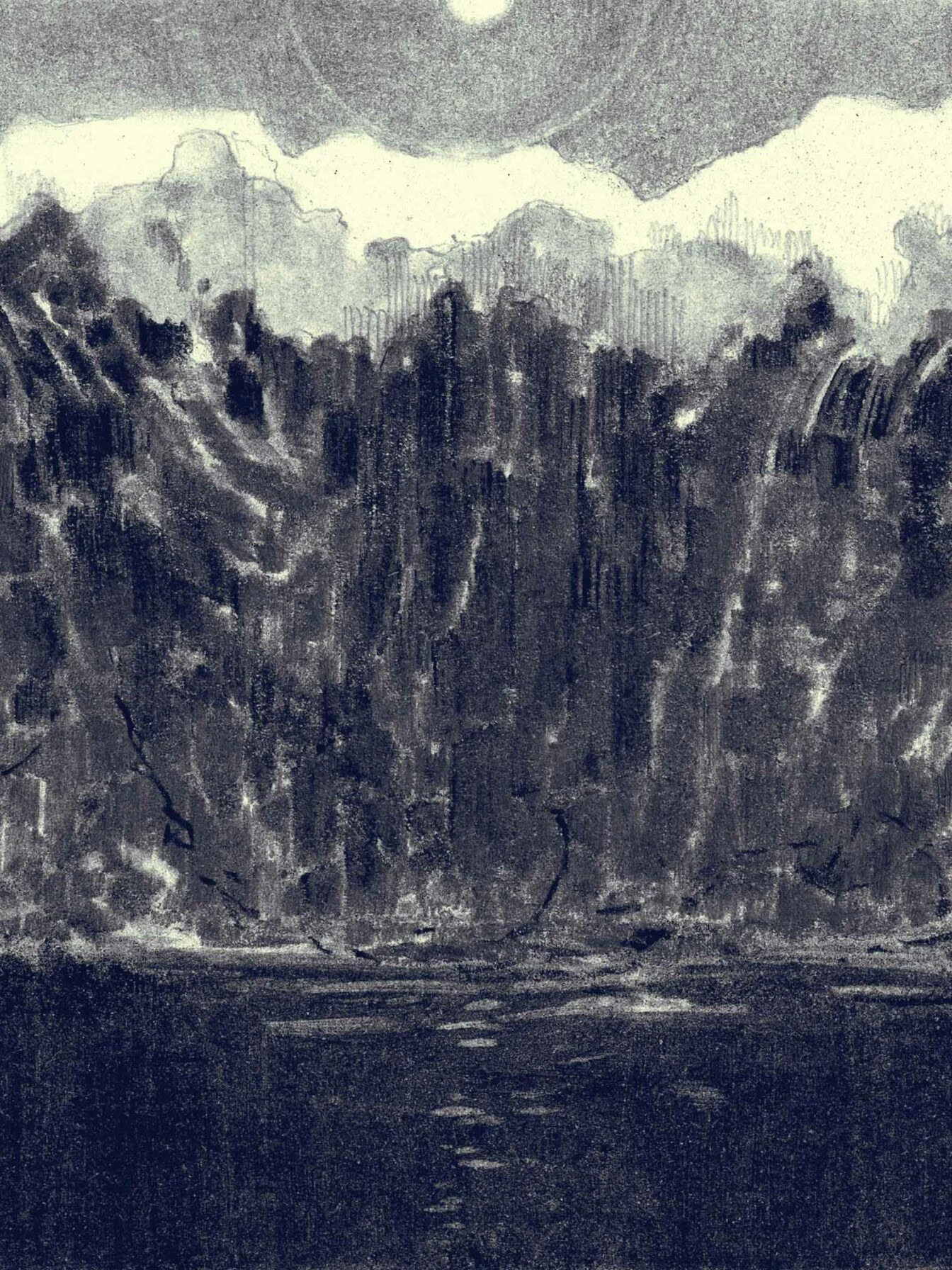

It was a three-mile trek, across town. It was dark. There was a full moon, but it was low in the western sky and pale, like a yellow button on a black dress. She went up Farmer’s Lane and turned west on Fourth Street, following the line of hills above town. She knew where Kobe·cha was but found herself lost in a maze of new streets and houses where only last fall she’d picked walnuts. She stopped, ready to turn back, when she suddenly realized that she was standing on a street corner where there were once clover fields, that the maze of new streets and houses now covered the jersey dairy also, for she could see the three enormous rocks of Kobe·cha, two and three stories high, and dwarfed below them the dairyman’s farmhouse. Following a street and then a dirt path, she found the place where folks picking walnuts used to pitch their tents, and then kept going until she was stopped by the remnants of a barbwire fence, all that was left of the dairy besides the farmer’s house. But from where she was standing, looking eastward, she could not see the house, only the rocks, yes, enormous, like huts in a village of giants.

She was surprised that in the dark she could see so well, the shapes of the rocks, the outlines of the trees, the water. She looked about for a streetlamp, though she knew she wasn’t close to a street corner, then saw the moon, not where she remembered it, low in the sky, but directly above her; not a yellow button, but a full white orb giving form to everything she saw, and reflected so large on the pond that it seemed the orb in the sky could just as easily have been a reflection of the one in the water.

She thought that she hadn’t been paying attention earlier, that she’d been rushing to find her way. She looked behind her, up the dirt path, and when she turned back to Kobe·cha she half expected the light to be gone. But it wasn’t. Then she figured it was close to dawn, that she wouldn’t make it back to camp without being discovered, and as she hurried along Fourth Street and then Farmer’s Lane, she felt she’d been foolish, completely mindless, and resolved never to leave camp in the middle of the night again. But the next night, no sooner had the Mexican retired his accordion than she was gone, even before the fires had turned to coals.

She found herself stopped by the barbwire fence, just as before. She heard voices and wondered if someone had seen her leave camp, or maybe had spied her from a window in one of the new neighborhoods and followed her. But the voices, soft yet clear even from where she was standing, came from below the rocks, she was certain of it. She stepped through an opening in the leaning fence and made her way easily to the rocks, avoiding gopher holes and low-growing shrubs lest they ply her clothes with stickers, for the moon was up again, over the trees and on the water. The rocks were huge, truly enormous. At the foot of them, she could not see the tops, which was why, staring upward, she did not see silhouetted in the moonlight the three figures seated on the ground below her. A woman and two men.

Her breath caught, but she was more embarrassed than frightened, as if she’d found herself inside a camp uninvited.

“I’m sorry,” was all she managed to say.

“Don’t be,” said the woman, who then pointed to an open space in the circle. “Make yourself at home.”

Isabel thought the woman might be making fun of her, maybe merely displaying the perfunctory kindness old-timers showed strangers. But these three people weren’t old and perhaps not all of them were Indian. The unusual light that was everywhere shone on them as bright as the sun. They were her age, in their twenties she thought, and wore contemporary clothes, the woman a sweater over her housedress, and the men jeans and long-sleeved shirts. One man was an Indian. The other two, Isabel wasn’t sure of. The woman’s hair, parted on the side, was wavy, betraying Spanish or Mexican heritage. The man was light-skinned; he could well enough have been a white man. With Isabel’s arrival, they’d stopped talking, and when they started again, seeming oblivious now to her sitting among them, Isabel found that what she had interrupted was a story they were telling.

“Waterbug wanted to kiss Quail Woman,” said the Indian man.

“And when he saw her take a drink of water, he wanted to know the water’s song so he could enchant her to kiss him,” added the woman.

“So, he stole the creek and wouldn’t return it until he forced the song out of the creek,” continued the light-skinned man.

This was the story of how Waterbug stole Copeland Creek. Isabel knew it and finished the story in her head. The mountain and everything all around dried up. There were no salmon in the creek. People were dying of thirst. Finally, Eagle, Waterbug’s ex-wife, took him in her talons high into the sky and forced him to spit out the song and return the creek, and then she dropped him so that when he hit the ground his legs bent clear around, which is why to this day he goes about the creek water backwards.

“Yes,” said the woman.

Isabel was startled. She thought that perhaps the woman had been reading her mind or, far worse, that she herself had finished the story out loud. Amid the silence that followed, Isabel grew more and more embarrassed, convinced that she had been rude.

“It’s an ancient story from Sonoma Mountain, from when the animals were still people,” Isabel said.

She thought one of them might show surprise now—that is, if she had indeed been silent before. On the other hand, if she had finished the story out loud, maybe one of them would comment on what she had said. But then no one said a thing. More and more, Isabel felt as if she was in a dream.

“You told the story because we are next to the pond at Kobe·cha and the water is dammed up. The white people trapped it—like Waterbug did to Copeland Creek. They thought they could do whatever they wanted without consequences,” Isabel said, speaking as much to herself as to the three people in the circle with her.

“We tell lots of stories,” the woman said. “Wherever we go.”

It was then that Isabel saw that the light on the three faces was beginning to fade, and just as the rocks had seemed the night before, they appeared to be retreating from her, and then all she could think was to hurry back to camp.

All the next day she thought about the three people. She wondered if she had indeed met anyone, for the more she pondered, the more she felt she had been dreaming. She’d behaved badly, she thought, hadn’t introduced herself but chatted on as if she’d known them forever. Were they workers who’d wandered from a camp nearby? The only crop this time of year was strawberries, and she didn’t know of any other strawberry farms nearby. Maybe they worked on a dairy; there were still plenty of dairies west of town. She seemed to recall that the light-skinned man and the woman were seated together, that perhaps they were a couple. She decided that she would return to Kobe·cha, simply to find out if what she remembered was true. It was not so much that she was nosey as that she needed proof that they were actual people, that she had walked to Kobe·cha in the middle of the night and hadn’t been dreaming. But when she reached the leaning barbwire fence, alarmed that already she could see them so clearly—a circle of light upon their faces brighter than the full moon—she forgot whatever reason she’d given herself for rushing across town in the dark.

Not one of them said a word to her. They gave the impression that they were familiar with her, that introductions were unnecessary, and that they had merely paused mid-conversation. But Isabel was anxious.

“Who are you?” she asked. Hearing herself, she could not believe her complete lack of manners, but then, just as she opened her mouth to introduce herself, the woman spoke.

“Hummingbird,” the woman said.

Isabel figured Hummingbird was a nickname. But no sooner had she heard the woman speak than she felt momentarily disoriented, even lost. She knew enough Southern Pomo to know “hummingbird,” enough English and Spanish too, but now she could not remember in what language the woman had spoken the word. Again, she wondered if the woman was Mexican or Spanish. Then the woman leaned into the light-skinned man next to her.

“You know who he is,” she said. “Yes, we are married.”

Isabel’s earlier impression was correct: they are a couple.

“I’m Rattlesnake,” the light-skinned man said.

Isabel grinned. Certainly, they were joking with her. She knew the story, from the time on Sonoma Mountain when the people were still animals. Men competed for Hummingbird’s heart. Fox offered Bobcat, Hummingbird’s father, mounds of acorns, enough to feed Bobcat for one winter. Skunk offered fresh blackberries, Raccoon a beautiful flicker feather headdress, and Mountain Lion a bow and sharp obsidian arrows. Rattlesnake, a rather ordinary man, had only a song to offer. Over her father’s objections, Hummingbird chose Rattlesnake, for the song benefited not just her or her father, but the entire village. Rattlesnake’s song called the crickets up Sonoma Mountain each fall so that, hearing the crickets, the villagers knew to prepare for winter.

“I know the story,” Isabel said, laughing out loud now. “Yes, Rattlesnake and Hummingbird got married. She knew he thought of other people, that’s why she picked him.”

Then the Indian-looking man said, “I’m Owl.”

And Isabel was confused.

“What does Owl have to do with the story?” she asked.

“Well, not that particular story,” answered the woman.

“But all of the stories are connected, like all of Creation,” added the light-skinned man. “That’s what we must remember.”

“So, I call you Owl?” Isabel asked the Indian-looking man.

“And me, Hummingbird,” the woman said.

“Rattlesnake here,” her husband said.

Isabel felt that they’d all been joking with her, that she was only playing along. But with the silence that followed, she quickly became uncomfortable.

“Yes,” said the man who called himself Owl, finally answering her question, “I’m Owl.” Then he asked her, “How do you think you got here?”

“And back to camp, both nights, so fast?” added Rattlesnake.

“You use my eyes to see at night and my wings to move silently and swiftly,” said Owl.

“You use my wings so that you don’t get tired,” said Hummingbird. “Oh, and during the day too.”

“You have my mouth, so you don’t get thirsty,” said Rattlesnake. “And during the day too.”

Isabel had to admit she hadn’t been thirsty during the day, or at night, for that matter. For the last two nights she’d gone to Kobe·cha and back to camp with ease, never once being discovered by anyone, from the camp or from one of the new neighborhoods. Suddenly she felt trapped: if it was a game she had been playing with them, it wasn’t a game of her own making.

“Why me?” she asked. “I don’t want any special powers. I don’t want favors.”

“That alone is a good enough reason,” said Hummingbird.

“Yes, we see that you are a good person,” said Owl. He spoke as if he’d just concluded a long study of her.

Rattlesnake shrugged. “You came here. What more?”

“Well, at least I know the story,” Isabel said, because she didn’t know what else to say. But already the light on the three faces was beginning to fade, and then Isabel was making her way back to camp, only to return to Kobe·cha the next night, just as fast.

They were there. The light on their faces was so bright that she could see they’d been waiting for her even before she reached the leaning barbwire fence. She took for granted now the strange occurrence of the full moon unchanged in the nighttime sky and on the pond’s surface, for, if anything, it reinforced the strange feeling she had of being in a place and time she hadn’t known before. All day she had doubted this feeling and her memory of what had happened over the previous nights. She told herself to drink water even though she was never thirsty, and she questioned how the three strangers at Kobe·cha knew the ancient stories. Two of them didn’t look like Indians. And hadn’t she forgotten to ask them where they were from? A work camp? A dairy?

“Who are you?” she blurted, forgetting her manners.

“We told you,” the woman calling herself Hummingbird answered.

“No, I mean really, who are you?”

They looked at one another confused, as if she’d spoken a language they didn’t understand.

“Do you work on a dairy?” she asked, seeing their confusion.

“No,” answered Hummingbird.

“We just go about,” said her husband, Rattlesnake.

“Well, actually we can work anywhere,” added Owl.

Once again Isabel felt as if she was being played with, and she was determined to get answers to her questions. She didn’t want to insult them, inquiring about their physical appearance, but she couldn’t help herself.

“Are you Indian?” she asked.

“I am,” answered Owl.

“I’m mixed with Mexican,” answered Hummingbird.

“I’m Irish and some German,” answered Rattlesnake.

Isabel wasn’t satisfied. Now more than ever she felt she was being made fun of, that what they were saying wasn’t true.

“Are you witches of some kind, poisoners or human bears? If you’re looking to recruit me, I don’t want to join you. I don’t want to do any bad things. I’m not mad at anyone. I don’t want to take vengeance on anyone. I’m not jealous of anyone…” Isabel continued, remembering stories of how a witch might recruit an unwitting young person.

Owl, seeing Isabel’s increasing frustration, leaned forward so she could hear him clearly. “We tell stories.”

“That’s all we’ve ever done,” Rattlesnake said.

“Of course, at the same time, we’ve become the stories ourselves,” added Hummingbird.

“But you’re not all Indian,” Isabel said.

“Anyone can become a story,” Owl answered. “An old story or a new story.”

“Isn’t that all anyone becomes?” said Rattlesnake.

“We’re just old stories in new human bodies,” said Hummingbird.

Already Isabel had begun to feel more comfortable, for even as her mind continued to whirl with questions, she could see their concern to help her understand.

“We’re as old as the rocks here,” Owl said.

“You don’t look old,” Isabel said.

“We don’t grow old,” Hummingbird said.

Then Hummingbird started telling a story, and after her, Rattlesnake, and then another was told by Owl.

Isabel returned to Kobe·cha and listened to stories, proud that she knew so many of them and charmed by the ones she was hearing for the first time. She was proud, too, of her special gifts, none more than her ability to escape at night unseen, as if her secret was itself a power she could hold over the others. Which was why, returning one early morning, she was frightened out of her wits to find a man silhouetted under the streetlamp at the corner of Fourth Street and Farmer’s Lane. At first, she thought he might be Owl or Rattlesnake playing a trick on her, perhaps acting the part of a story they’d told her. But he wasn’t. As she drew closer, she saw the man was Rodrigo, the work camp supervisor, her cousin’s husband.

“We know where you’ve been,” Rodrigo told her.

Isabel said nothing, but as she followed him back to camp, she felt she was being apprehended.

Apparently, Rodrigo, on his way to the latrine, had happened to glimpse Isabel slipping from camp. He waited and watched her a second night, then deployed two of his friends to follow her through the new neighborhoods, as far as the dirt path that led to Kobe·cha.

“So that’s how we know where you’ve been,” said her cousin’s husband before returning with his two friends to their campfire.

Isabel was frightened they might have seen her below the big rocks, her face and those of her companions lit by the bright light. At the same time, she was furious that they had followed her, for what business of theirs were her whereabouts? In the days ahead gossip spread through camp, though little was said to her directly.

“Do you meet a man there?” asked the cousin whose husband had followed her.

When an old man snapped, “Your people are from Sebastopol, from the lagoon. Kobe·cha is not your ancestral village. What business do you have going there?” Isabel, though she didn’t say anything, had an answer for him. Water is water. It’s connected everywhere.

She missed her friends at Kobe·cha but didn’t dare leave camp lest someone follow her again and discover them. In the evenings, each long minute that she sat near the fire disproved whatever stories they had been telling about the woman who traveled at night to Kobe·cha. They were now just that, stories. But she was torn. Even as she wanted to protect her friends, she felt betrayed by them, as if in the end she had in fact been foolish to believe them. Which was no doubt why, when she found herself seated among them again, she was thinking only to get an answer to her question.

“You gave me a mouth so I don’t get thirsty,” she said to Rattlesnake, and to Hummingbird, “You gave me wings so I don’t get tired.” Then she looked at Owl. “And you gave me eyes to see at night and wings to move silently and swiftly.” She took a deep breath then blurted out, “So how did I get caught?”

Owl looked to Hummingbird and Rattlesnake. They appeared confused, just as they had when she asked them who they were, as if she’d spoken a language they didn’t understand.

Then finally Owl spoke.

“You are not all-powerful. No one is. Have you forgotten the power of humans? They are tricksters, they are clever. That is their power. They can trap anything. They can trap the water. They can trap animals and even one another. But they forget the limits of their power, and when they forget, harm and destruction follow. The water dries up. Plants and animals disappear. Isn’t that what the stories we’ve been telling remind us of? You got trapped. You thought that with the gifts you have you were all-powerful.”

Isabel thought of the water trapped in the storm drains on every street corner of the new neighborhoods. She thought of the deep blue pond now trapped by steep concrete walls. And wasn’t it just a few weeks ago, when they first arrived at the camp, that she witnessed her cousin’s husband shoot with determination every last strawberry-eating crow? She felt foolish now. Ha!, she thought to herself, this all started with a strawberry getting away from me. But to her amazement she’d been speaking out loud, for Hummingbird immediately rejoined, “Oh, it started before that. It’s just that when that happened, you started to pay attention.”

“And now you’ll always pay attention,” added Rattlesnake, “and you will be able to come back and join us safely.”

Isabel thought she heard Rattlesnake continue, launching into a story, but she wasn’t certain, for the next thing she knew she was awake on a bedroll. The sun was up, and her cousin was saying, “It’s late. Get up. Last day of work here, or did you forget?”

Isabel followed her cousin and the others to another work camp—hops, and after that, prunes and pears. If she heard talk of her night journey to Kobe·cha, she smiled to herself and merely went on her way. She married an Indian and had three children. For years people continued to tell stories about a woman at Kobe·cha, eventually without naming her, no doubt because anyone who might have known her from the strawberry camp had passed on. They claim to have seen a woman near the water. Neighbors tell of waking at night to the sound of voices, people talking. Today there is nothing left of the pond but a square of dirty water. Even the rocks are gone, moved to make way for a swimming pool. Still, it is said the woman is seen there now and then. She looks the same, about twenty-five years old and plain. She never grows old.