Fred Bahnson is the author of Soil and Sacrament, and his essays have appeared in Harper’s, The Sun, Orion, Oxford American, and Best American Spiritual Writing. His essay “On the Road with Thomas Merton,” originally published in Emergence Magazine, was selected by Robert MacFarlane for Best American Travel Writing 2020. He is a recipient of a W.K. Kellogg Food and Society Fellowship, a North Carolina Artist Fellowship, and a Terry Tempest Williams Fellowship for Land and Justice at the Mesa Refuge. He lives with his family in southwestern Montana.

Jeremy Seifert is an award-winning film director, cinematographer, and editor whose documentaries have premiered at Sundance, Berlinale, Hot Docs, Tribeca, and AFI DOCS. His feature films include The Devil We Know, co-directed with Stephanie Soechtig; and the award-winning documentaries GMO OMG and DIVE! Living Off America’s Waste. His short documentary for Emergence, The Church Forests of Ethiopia, premiered on New York Times Op-Docs. Jeremy is a frequent contributor to Emergence Magazine.

Nearly all of Ethiopia’s original trees have disappeared, but small pockets of old-growth forest still surround Ethiopia’s churches, living arks of biodiversity amongst the brown grazing fields. In this film and essay, Jeremy Seifert and Fred Bahnson travel to Ethiopia to gain a deeper understanding of how our fate is tied with the fate of trees.

The Seen and the Unseen

In the forests of northern Ethiopia, there are said to dwell large numbers of invisible hermits who intercede on behalf of all humanity. Menagn, they are called in Amharic. According to Ethiopian Orthodox cosmology, hermits rank just below angels in importance, making theirs the most efficacious of all human prayers. To have one of these holy men living and praying in your forest is considered a special blessing, even if you never see him.

About the hermits’ lives, little is known. They appear rarely, and only then to those with the eyes of faith, yet their presence in these forests is undisputed. They might accept an offering of dried chickpeas or a handful of roasted barley left in a clearing, but mostly they subsist on leaves, bitter roots, and prayer. They wear shabby clothes, unkempt beards, dreadlocks. Only the holiest of them achieve a state of invisibility. When someone manages to see them and attempts to take their picture, it is said, their image will not appear in the photograph. A hermit might live in a particular forest for years, going about his hidden work of intercession, and then one day someone walks by a juniper tree and discovers a pile of his bones.

I live in a temperate rainforest in western North Carolina. I visit the woods often, sometimes with my wife and sons, sometimes alone; whenever I enter a forest, I can’t help but fall into reverie. Increasingly the woods for me have become a place to ponder, to pray and contemplate, so much so that the woods have come to be inseparable from my spiritual life. Several years ago when I first read about Ethiopia’s church forests, it seemed that I’d stumbled on my own symbiotic relationship, albeit one that had already been thriving for sixteen hundred years. I made plans to visit, bringing with me many questions about the geography of faith, but also about different ways of knowing that often seem in conflict and which our age seems unable to resolve: our desire for certainty and our hunger for mystery.

My search led me to a man who embodied that tension, and who has dedicated his life to studying and preserving Ethiopia’s last primary forests. This is a story about trees and hermits, but it is also the story of this man, of his love for both.

Photo by Fred Bahnson

The Hinterlands

On a hot morning in late February, Dr. Alemayehu Wassie crossed a dusty field toward a forest surrounded by a stone wall.

As he approached the wall, dozens of worshippers emerged through a gate. They were clad in white shawls, returning home from a wedding, and on their necks they wore small wooden crosses. Some of the women wore crosses tattooed on their foreheads. They left the forest slowly, in silence.

Alemayehu motioned me toward the wall so that I could see the forest beyond. This was a quick stop. Soon a busload of fifty local priests from across the South Gondar province would arrive for the start of a two-day tour, but first Alemayehu wanted me to see Zhara, the place where it all began. Alemayehu had convened the gathering along with his friend and colleague Dr. Margaret “Meg” Lowman, an American ecologist and canopy biologist, with whom he had worked for the past ten years to conserve Ethiopia’s church forests. Each year they taught a workshop for priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedu Church, which traces its roots back to the fifth century. Normally they hosted the workshops indoors, showing PowerPoint slides and Google Earth images of the church forests. But this year the two ecologists had rented a bus. They wanted to show the priests the newly completed conservation wall at a place called Zajor, in hopes of inspiring them to protect their own church forests, but first we stopped here at Zhara, the first church forest to be conserved.

When he decided to become a forest ecologist, Alemayehu realized that in order to study Ethiopia’s native forests, he would have to study the forests surrounding churches. Until roughly a hundred years ago, Ethiopia’s northern highlands were one continuous forest, but over time that forest has been continually bisected, eaten up by agriculture and the pressures of a growing population. Now the entire region has become a dry hinterland taken over almost entirely by farm fields. From the air it looks similar to Haiti. Less than three percent of primary forest remains. And nearly all of that three percent, Alemayehu discovered, was only found in forests protected by the church.

“I was amazed to discover that,” he said.

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

The pressures on these forests, especially from cattle grazing, were easily identified; the question of why they persisted was a puzzle. To solve this puzzle Alemayehu went to Europe to complete first a master’s degree then a doctorate in forest ecology, returning to Ethiopia each year for his field research. Alemayehu chose twenty-eight forests on which to focus his research, sites representing all of the known endemic tree species, and the more he studied them, the more he understood their significance. “I was hooked,” he said. “Church forests became not only my profession, but my emotional and spiritual connection.” But he also saw how quickly the forests were disappearing, some from deforestation, most from cattle grazing. When Alemayehu met Meg at an ecological conference, she introduced him to Google Earth. They estimated that there were nearly twenty thousand tiny church forests in the Ethiopian highlands, scattered like emerald pearls across the brown sea of farm fields, and most of these were no more than eight or ten hectares. While viewing the Google Earth images, Alemayehu and Meg hatched a plan: they would use these images to educate priests, showing them how much forest had been lost, and also how much was still worth saving.

With the permission of the local priest, he and Meg chose Zhara as their pilot project. Zhara was rich in biodiversity. During his initial research Alemayehu counted over forty-six tree species in this one forest alone. Yet it was becoming degraded. “When I first came to Zhara in 2002,” he said, “the forest floor was trampled. Like the dirt floor of a house.” He found no regeneration, no young seedlings emerging. Cattle had trampled or eaten everything within browsing height. A harsh microclimate dominated. Trees on the outer perimeter bordering farm fields were stressed; when Alemayehu returned a year later, some of those border trees had died.

“I said to myself, ‘this forest is not going to last.’”

As part of the pilot project, Alemayehu and Meg offered their first workshop to the priests on how better to conserve their forests, and it was at this workshop that the idea for the wall first arose. It came from the priests themselves. They would enlist local villagers to take stones out of the surrounding farm fields and build a dry-stack stone wall around the forest. Meg raised money for a gate and for trucking the stones. They built the first wall at Zhara in 2010, expanding the forest boundary from eight to ten hectares. Very quickly the process of regeneration began. The inner forest became more secure, the air more conditioned. Birds returned. Wild animals increased. The number of pollinators grew.

The conservation wall was working, but this was only one forest. What of the twenty thousand other church forests in the Ethiopian highlands? As they narrowed down a list of conservation priorities, they quickly faced a definitional challenge. What represents a forest? Is it five trees? Five hundred trees? Could it be a degraded site, or does the forest have to be beautiful to justify conserving it? In the end they chose forty forests, those that contained the highest biodiversity and could serve as a genetic seedbank along the elevation gradient.

If they could save these forty forests, then perhaps one day, they hoped, the native forests of the Ethiopian highlands could be restored.

The Journey

Up ahead on the forest path, a dozen or so men approached, surrounding an elderly man dressed in a yellow robe. Alemayehu walked over, bowed low, and kissed the man’s wooden cross. By the way people attended the elder, followed him, watched his every move, it was clear he possessed some kind of authority. I wanted to ask Alemayehu who this man was, but just then a horn sounded out on the road. The bus full of priests had arrived.

We rejoined Meg, who was waiting back at the Land Rover, and set off for our main destination, the bus lumbering behind us. Earlier that morning we had left the city of Bahir Dar, a city on the southern end of Lake Tana, and now we were on the road to Zajor. We traveled for the next hour on increasingly deteriorating roads, until finally we left roads altogether, jouncing over dusty farm fields bisected by dry riverbeds. There were eight of us packed together in the Land Rover: Alemayehu and the driver up front, my friend and filmmaker Jeremy Seifert, Dr. Meg Lowman, and myself in the back, and hunched in the very back, Tegistu the translator and several priests we’d picked up along the way. Even as the road deteriorated, a jocular mood prevailed. A full day of adventure awaited us.

We were bound for a special place, Alemayehu explained: the church forest of Zajor. According to local tradition, when the Ark of the Covenant was brought to Ethiopia some three thousand years ago by King Solomon’s son Menelik I, it rested for a time at Zajor. The place has long been known for its hospitality. Of the dozens if not hundreds of church forests Alemayehu has visited and surveyed in his work as a forest ecologist, Zajor was his favorite.

As we bounced over fields and navigated the steep ravines, I decided to ask the question I’d been holding ever since I first learned of the church forests and their conservation walls. Back home in the US, I said, there was much talk of walls just then. Trump was whipping his followers into high dudgeon with frothy “build the wall” rhetoric, and a lot of us were scared he might actually follow through with his intended xenophobic construction project. I then asked Alemayehu the question that had troubled me since I first read about the conservation walls: why erect barriers? Did the world really need more walls?

“I like walls,” Alemayehu said. He chuckled.

A small-framed man of quiet demeanor, he suddenly grew expansive, throwing open his arms in mock welcome, and shouted out the window of the Land Rover, “Mr. Trump, I want you to build your walls here! These Americans don’t understand you, but I understand you, Mr. Trump! When you say you want to build a wall, I believe you! We can work together. Just take a fraction of that money you want to spend on your border and give it to Ethiopia—in two years we can provide you with more walls than you ever dreamed!”

We all laughed. Nothing like a shared tyrant joke to foster international cooperation.

“Ah,” Alemayehu said, “here we are.”

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

Like many church forests, Zajor was set on a hill. Before climbing to the forest edge, we had to first navigate one final ravine. As the Land Rover slowed to begin its descent, a group of boys ran up beside us, laughing and making traffic cop signals. We dipped into the dry riverbed and climbed the steep bank beyond, then someone gave a shout. Behind us, the bus was inching down into the ravine, its nose pitched at a dangerously steep angle. For a moment it hovered over the ravine, perched on three wheels. Then it leveled out and pulled up the far embankment. Everyone cheered. We parked in a large field below the hill and disembarked. The priests emerged from the bus, their flowing white robes radiant against the dry brown fields, and together we walked en masse up toward the forest of Zajor.

It was beautiful, even from a distance. From every point in the landscape, the eye would be drawn exactly here, its gaze traveling over the surrounding brown fields with no rest, until it arrived on this sudden lushness bursting with every shade and hue of green. Surrounding the forest was a handsome new stone wall, contouring around the hill in both directions toward the horizon. It was an inviting place, a place where had you been walking for hours across this dry, hot landscape, as many people did before arriving here, you would be instantly drawn to this place of coolness and rest. “City on the Hill” was an ancient scriptural metaphor for the place where God’s people gather, but here, I thought, was an improvement on that old trope, one more fitted for the Anthropocene age, less militant fortress than mystical refuge: the Forest on the Hill.

I followed Alemayehu up through the dry fields. When we reached the outer wall he paused, waiting for the men in flowing white robes to join us. We were met at the gate by several priests in white tunics, a welcome party. Leading them was a gray-haired priest holding an ornately carved staff. “I love this guy,” Alemayehu said, as he walked over to greet him. “It’s such a pleasure for me to come here.”

The Outer Wall

When all the priests had gathered beside the wall, Alemayehu paused for effect, then began his pitch.

This land was once completely forested, he began—sweeping his arms across the surrounding countryside—so much so that nobody would have seen the church. It was all trees. Now almost all the old forests have been cut down. The only place where they are still protected are in church forests like this one. When the people here at Zajor decided to build their wall, he said, they were not bureaucratic, they just built a wall. He motioned to the elderly priest with the carved wooden staff and thanked him for initiating the project. Alemayehu hoped other priests would be inspired by this community’s example.

As we stood beside the wall, a stream of local parishioners came and went through the gate. This is what Alemayehu meant when he described the wall as “porous.” A group of children hopped on the wall and ran down its length to the west until they rounded the corner and were lost to sight. An elderly woman approached. She stopped beside the wall, crossed herself three times, then bowed low at the waist and began to fan her face with both hands, cupping the air and pulling it toward her, as if partaking of some invisible goodness that lay inside the wall. Then she rose and walked solemnly up the forest path. Clearly this was no mere border fence; it was an entrance into the sanctuary.

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

Perhaps I was witnessing more than gestures of devotion, important as they were. Maybe they were also the secret to conserving the forest, small acts that together with hundreds of other gestures like them formed an invisible shield around the forests of Zajor. As I would come to learn, this shield was embedded deep within the structures of belief that had survived here since the fourth century. Our Western conceptions of belief are almost entirely inward and private. Here, and at other points on my journey into these forests, I was witnessing the performance of a mystical geography, the soul’s journey to God made visible in the landscape.

Churches in the Ethiopian Orthodox tradition inherited many of their ideas of sacred space from Judaism. The center of their church, like the metaphorical center of the Jewish temple, is called the qidduse qiddusan, the Holy of Holies. In that center rests the tabot, a replica of the biblical Ark of the Covenant, another borrowed symbol. Only priests can enter the Holy of Holies. Enclosing this sacred center is a larger circle—the meqdes, where people receive communion—and outside that lies a still larger circle called the qine mehelet, the chanting place. All three spheres are contained under the round church roof, but those circles ripple outside the church itself.

Beyond the church building lies the inner wall, which forms a circular courtyard around every church. According to tradition, the proper distance this wall should stand from the church is the armspan of forty angels. During my visits to different churches, I watched many people enter these inner courtyards. Before crossing the threshold, they performed various gestures of piety—crossing themselves three times, dipping a knee, perhaps kissing the wooden doorframe. It was clear to everyone that when you crossed the inner wall, you were entering holy ground.

The brilliant move the priests made was to take the idea of the inner wall and replicate it. Using the same design, they built a second wall of dry-stacked stone just outside the forest boundary, thereby extending the invisible web of sanctity to include the entire forest. Suddenly the holy ground surrounding the church expanded from the size of a backyard to a vast tract of ten, fifty, or even several hundred hectares. Once Zajor’s outer wall was complete, people could no longer cut trees along the perimeter, nor could cattle trample or browse young seedlings. Every tree, animal, and hermit was now sheltered under the church’s protection.

“In our tradition, the church is like an ark. A shelter for every kind of creature and plant.”

By extending the boundaries of what they consider sacred, the Orthodox Christians of northern Ethiopia are not only protecting their own forests; they are offering a pattern for how we might tap into our deep cultural memory reaching back hundreds if not thousands of years, and put that memory to work on behalf of the web of life.

When it can be channeled, there is no force on earth more powerful than the religious imagination.

As I stood outside the forest wall at Zajor, this stone barrier before me seemed a near-perfect solution. Labor was plentiful, so there were ample people to help build the walls. Stones of volcanic basalt were freely available in the surrounding farm fields, and local farmers were happy to have them removed. In a place called Wonchet, another church forest I visited, the priest described the process: Fifteen volunteers from four surrounding villages came each day, rotating in and out. They averaged fifty linear feet of wall per day. Working straight through, it took them two months to complete. Meg raises money to pay for gates, for trucking costs to carry stones to the building site, and for stone masons who direct the work. The conservation walls do many things—serving as a habitat for rodents, lizards, snakes, and insects, for example—but most importantly they address the devastating effects of cattle grazing. With the wall in place, cattle are excluded, while people can come and go. “The wall is porous,” Alemayehu explained, pointing to the people entering the forest. “Humans can come here any hour of the day to contemplate or pray or collect seeds.”

Contemplate. Pray. Collect. Ecclesial verbs transformed into forest verbs.

I had other questions for Alemayehu, questions about the distance a forest’s sanctity extended. And what of the surrounding farm fields, were they not considered sacred? I understood the need to keep out cattle, but wasn’t the wall a sign of retreat? With twenty thousand church forests, how could they possibly protect all of them? And what of the hermits he spoke of, and their invisible work of intercession?

But these questions would have to wait. There beside Zajor’s wall, I stood before a series of concentric circles radiating outward, as though the tabot were a stone tossed onto the landscape, sending invisible ripples of holiness out into the world. Here was the culmination of sixteen hundred years of religious imagination, and I was about to walk into its center.

The Forest

I felt the change first on my skin.

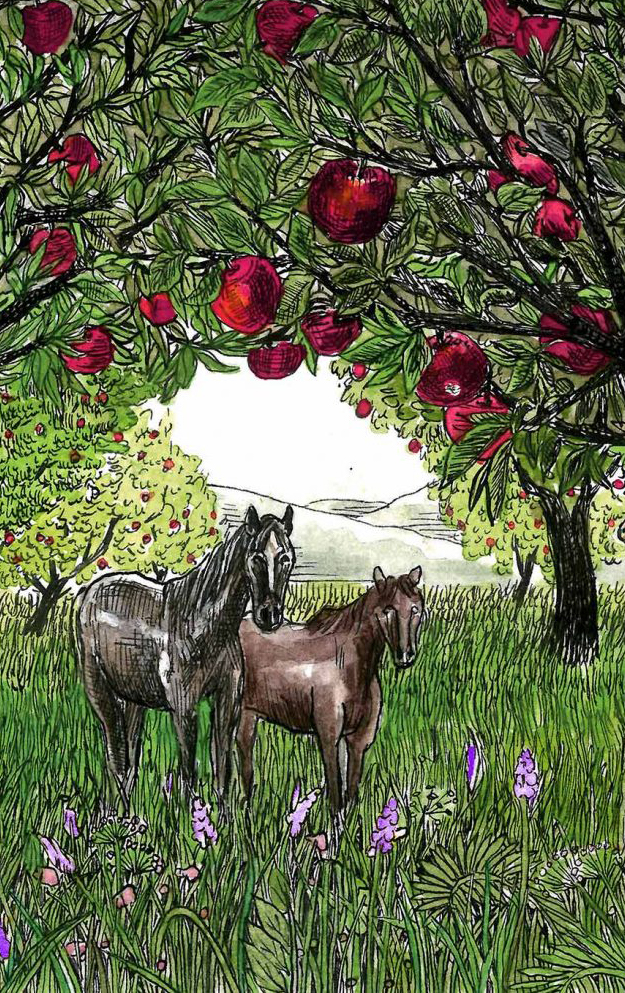

Moments ago outside the wall, we stood under a cloudless sky, sweating in the morning sun, but here under the forest canopy the air was cool and pleasant. The temperature had dropped a good ten degrees. All around and above us, the forest came alive. A flowering donga tree, Apodytes dimidiata, gave off a pungent jasmine-like perfume.

I asked Alemayehu about the names of trees. In our previous conversations I noticed how he wore his learning lightly, always assuming the other knew more than he did, when in fact he was one of the most knowledgeable scientists in the world about these forests. Now in his element, he rattled off a slew of Latin names: Carissa edulis, Prunus africana, Ficus vasta, the holy fig. We walk past a large Juniperus procera, the African juniper that, according to Ethiopian Orthodox tradition, is the tree on which Jesus was crucified. A mating pair of hammerkops, one of the many bird species here, nested in the donga. Further up in the canopy, dark forms emerged, leaping between branches: vervet monkeys. Other creatures lived here, too: rodents, porcupines, tree squirrels. Though I didn’t see any, I learned that the church forests were home to even larger animals, like wild pigs, gazelles, and rare civet cats.

“These forests are not just good for people,” Alemayehu said, “they are also the last shelter for wild animals. In our tradition, the church is like an ark. A shelter for every kind of creature and plant. If a wildcat or little kudu or vervet monkey leaves the church forest, immediately he will be killed. Here the animals are safe.”

In a previous conversation, Meg had described the church forests as a modern Noah’s ark. In the coming days I would think back often to that image, reflecting on the ways in which these forests were living arks of biodiversity, tiny green vessels sailing over a barren sea of brown. In this time of rising waters and diminishing life, the church forests of Ethiopia are in many ways the perfect metaphor. As we sail into the Anthropocene bottleneck, a constriction of our own making, places like Ethiopia’s church forests offer a vision of a future that we are making even now. We will need many more arks like them, tens of thousands of arks: cultural, biological, spiritual. Only then will we survive the storms that are surely coming, that have already arrived.

Whatever we make of the Noah’s ark story, it’s clear that we face a flood of our own making, only this time there are multiple catastrophes: carbon warming the atmosphere, acidifying oceans, species loss, deforestation. How much of Life we carry through the bottleneck will largely determine the kind of world we will have on the far side of carbon stabilization.

In many ways, the vision of our shared future appears bleak. Only three percent of Ethiopia’s original forests are left, but that is also true of the United States. Most of what we Americans know as forests are secondary or tertiary growth, and in both countries the remaining genetic material is under threat. In a place like Ethiopia, is it reasonable to expect that stone walls and religious rites will prevent the onslaught of biodiversity loss?

There is no great victory in this story, not yet. During my visits to different church forests, I began to feel there was something poignant, almost melancholic, about how much biodiversity remains under threat. Only fourteen forests out of the intended forty have been protected—a mere thimble of biodiversity—and after that there are twenty thousand more. How to ever slow the deluge? How to halt the steady erosion of life?

And yet there is also something quietly heroic about such efforts, a stubborn hope that refuses to despair, that refuses to countenance that world-weary climate apathy to which so many of us in the Western world have fallen prey.

The trees’ fate is bound to ours, and our fate to theirs. And trees are nothing if not tenacious.

“Humans can come here any hour of the day to contemplate or pray or collect seeds.”

From the beginning of human history, our lives have been entwined with the life of trees.

The scientific way of knowing has taught us many things about these beings. Forests draw down as much as a quarter of all our carbon emissions, making trees one of the most crucial technologies in the fight against climate breakdown. In the UN’s Special Report on Climate Change and Land released August 7, 2019, scientists stated unequivocally: “Our planet’s future is inextricably tied to the future of its forests.” This report and others like it alert us not to the “fate of the Earth,” an abstraction, but to the very specific question of our own survival.

“Trees are the longest-living life form we know,” reports a recent article in Aeon magazine, “and manifest their temporal and geographic histories within their very bodies.… Alongside humans, trees are the dominant drivers of terrestrial biogeochemical cycles in the Anthropocene, influencing the Earth’s environment in ways that no (nonhuman) animal can.”

The article poses this intriguing question: “If trees are not simply the environment, but active participants within it, then what exactly is the tree-environment relationship, and what can trees teach us about the very idea of an ‘environment’?”

This article is but one of many voices now asking us to consider what indigenous cultures like the Orthodox Christian people of Ethiopia have long known is true, that trees are not a green backdrop against which all our vaunted human dramas play out, but actors in their own right, performing what Primo Levi called “the solemn poetry of chlorophyll photosynthesis.” Thanks to several decades of research on the fungal networks of mycorrhizae, we know that trees enact a surprising degree of agency. They respond to threats; nurture their young; share nutrients, even with unlike species. Most intriguing of all, through the mediums of leaf chemicals and underground strands of mycelium, trees communicate.

All of which make trees seem more like slower, or perhaps less frantic, versions of ourselves.

The scientific way of knowing is only one form of human knowledge. There are roots that reach deeper still, into the subsoil of human history, revealing more subtle, more intimate forms of tree-human symbiosis. Some of these resemblances are discomfiting, for trees “symbolize the ongoing transformations, and thus corruptions and degradations, associated with the living body: from growth to decay and eventually death. In other words, before us and in plain sight, they present precisely that from which we want to distance ourselves.”

During my visit to the church forests of South Gondar, that tree-human relationship manifested at every turn. As Alemayehu put it during our earlier visit to Zhara, “A church without a forest is like a naked person. A disgraced person.”

As we enter the Anthropocene bottleneck, it seems that so many of us around the world are on our way to becoming disgraced people, shorn of our forest clothing. “In my lifetime,” Meg told me, “we’ve lost fifty percent of the world’s forests.” How we love individual trees, but how we forget that our tree is embedded within a community of beings—a forest—without which that individual could not exist. It is only through relationships that a solitary tree is able to survive. So, too, ourselves.

As we walked deeper into the forest of Zajor, Alemayehu grew animated as he described all the ways trees support his fellow Ethiopians. “Trees are life,” he said. “They are a game changer for developing countries.” One of the crucial roles forests play for agriculture is to serve as a home for pollinators. As he explained, pollinators are the crucial ingredient to produce seeds for farmers. A farmer can till and plant, and rain may come, but unless there are pollinators, there will be no crop.

Trees also mean water. Without trees, water cannot infiltrate the ground and recharge the groundwater, which later comes up as springs. People depend on wells or springs for their water source. Without trees, those springs run dry. Most people here cannot afford to buy Western drugs or pharmaceuticals. When they need medicine, they go to the church forest; for Prunus africana, for example, or Hygenia abyssinica. Cures for stomach or prostate or liver—all of these are treated with trees.

Just as the presence of trees confers human health, their absence invites diseases, like malaria. That disease was once confined only to the lowlands, Alemayehu explained, but as a result of climate change and deforestation, mosquitos are moving up the elevation gradient. Malaria has now come to the highlands.

“Forests are really mystical, holy, sacred places,” Alemayehu said. In Amharic the word for forest is ch’aka, which means “wild.” It can also mean “mystery.”

And yet for Ethiopian Orthodox Christians, Alemayehu explained, there are no sacred trees, for that would imply tree worship. Trees are revered, loved, and cared for, but they can still be cut: like the juniper, the tree on which Jesus hung, which is occasionally harvested for the construction of new churches. As we walked through the forest of Zajor, I saw several junipers that had recently been felled, intended as gifts to a nearby village who wanted to build a new church. Certain trees in the Ficus genus are considered to be especially revered. I often saw a number of these massive figs, Ficus vasta, growing at the entrance to a forest, many of them half a millennium or older.

Seeing the freshly cut junipers laying on the forest floor, or finding a plastic water bottle here and there beside the trail, I was reminded that the church forests were not pristine wilderness. Here was a kind of paradise, yes, but a usable paradise.

Watch the companion film, The Church Forests of Ethiopia, by Jeremy Seifert

The priests chatted in low but excited tones as we walked down the forest path, and as we progressed deeper into the forest, I asked Alemayehu more about how trees have shaped his spirituality.

“In the Bible, trees are symbolic of the presence of God’s mercy,” Alemayehu said. “In the Psalms, King David says, ‘Don’t leave me in the desert where there are no trees.’ Well, he doesn’t mean that literally. He means he doesn’t want to be left without God.” Places without trees and water are presented as departing from God.

Alemayehu recounts the story of Genesis, where God places the human in the garden “to keep it and dress it.” He likes that verse, because it shows the role humans have in caring for our earthly paradise. To “keep” implies preservation, while to “dress” means to develop or enrich. Alemayehu sees our role as both safeguarding biodiversity, but also “dressing” the barren places, helping that biodiversity spread. “This is a place of worship, or prayer, contemplation, devotion,” he said. “This is the best place to keep our biodiversity.”

Alemayehu spoke often in our talks of biodiversity. I asked him why it was so important. “In this world nothing exists alone,” he said. “It’s interconnected. A beautiful tree cannot exist by itself. It needs other creatures. We live in this world by giving and taking. We give CO2 for trees, and they give us oxygen. If we prefer only the creatures we like and destroy others, we lose everything. Bear in mind that the thing you like is connected with so many other things. You should respect that co-existence.” As Alemayehu explained, biodiversity gives rise to a forest’s emergent properties. “If you go into a forest and say, ‘I have ten species, that’s all,’ you’re wrong. You have ten species plus their interactions. The interactions you don’t see: it’s a mystery. This is more than just summing up components, it’s beyond that. These emergent properties of a forest, all the flowering fruits—it’s so complicated and sophisticated. These interactions you cannot explain, really. You don’t see it.”

Like the prayers of hermits, which also were part of the forest’s emergent properties, invisible to the untrained eye.

The trees’ fate is bound to ours, and our fate to theirs. And trees are nothing if not tenacious.

As we continued through the forest on our way to the church, I enlisted the help of our translator, Tegistu, to speak to one of the priests. I asked him why these forests were important. “It’s our duty to protect the church forest, because hermits live here. They don’t have houses. They live deep in the forest.” He pondered for a moment. “And the forest is important, because the church should be a symbol of paradise. The Garden of Eden was full of trees, fruits of all kinds. So a church should always be surrounded by many different kinds of trees to symbolize paradise.”

I heard similar responses from other priests and monks I spoke with during my visit. Occasionally one of the more educated priests would mention how trees provide medicinal value, or provide habitat for pollinators, or produce oxygen, but for the most part people here did not think in utilitarian terms. They knew the value trees gave, but they weren’t first concerned with what trees did for them. Forests needed protecting because they were symbols of paradise—and because forests provided a home for hermits.

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

The arrival of Christianity to Ethiopia could be said to date from the first century, when the Ethiopian eunuch mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles first adopted the faith, but the official arrival is ascribed to a group of Syrian monks in the fourth century, when the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became official state religion. Later known as the Nine Saints, the Syrian monks brought an ascetical faith that two centuries earlier had sprung to life out of the barren deserts of Egypt with the flowering of Christian monasticism. Ethiopian Christianity has to this day retained its monastic character, and this includes a deep reverence for solitude.

As Christianity spread through Ethiopia, so too did the rise of anchorites, religious recluses. Like their counterparts in northern Africa, Ethiopian hermits sought out remote places for their abodes. In the desert lands of Tigray, they lived in caves or cliff dwellings, but when they spread into the lush highlands of Gondar, the hermits took refuge in forests. They became dendrites: tree dwellers.

It seems that hermits across the ages share certain arboreal similarities. In his classic The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James mentions St. Peter of Alcántara, a medieval hermit renowned for his feats of asceticism, whose body was “so attenuated that it seemed formed of nothing so much as of so many roots of trees.”

The work the menagn of Ethiopia have practiced for at least fifteen hundred years is the quiet, unseen work of intercession. They hide themselves not to escape society, but to pray for the healing of the world, and for that work they are much revered. A description from the fourth-century text Historia Monachorum describes early Christian monastics of northern Africa, but it well captures the attitude of the Ethiopian Orthodox faithful toward their own menagn: “It is clear to all who dwell there that through them the world is kept in being, and that through them too human life is preserved and honored by God.”

“I once wrote a novel about hermits,” Alemayehu told me. “A mystical novel. This phenomenon, it’s part of our culture.” This was in response to one of my questions about the menagn during one of our long, bumpy rides in the Land Rover. He mentioned it almost in passing. I silently added “novelist” to my growing mental list of Alemayehu’s gifts and accomplishments. He was hesitant to speak of it, but when I pressed him, he began to recount his strange encounters over the years with various menagn.

Did I remember the elderly priest in the yellow robe, the one surrounded by followers whom we saw that morning at Zhara? He was a hermit. It was rare for him to be seen, Alemayehu explained. He had appeared for the wedding.

In Ethiopian monastic life, a monk might decide to go to a far mountain, or a dense forest. There he will spend the rest of his life immersed in prayer. During his years of research, Alemayehu has come upon signs of a menagn: a water bottle; a necklace of wooden prayer beads hung from a branch. Sometimes he came upon what he called “a praying place” in the woods. He felt a nearby presence, even though no one was visible.

“When you first encountered this phenomena,” I asked, “did you find a conflict within yourself between the scientific Alemayehu and the mystical Alemayehu?”

He laughed. Yes, he said. At first he was skeptical. He asked himself, Am I really experiencing this? But the encounters were too many for him to discount. Eventually Alemayehu became convinced not only of the invisible menagn’s presence but also of their protection. In some of the forests there were dangerous wild animals, even pythons. But he was never harmed.

Once when he was a PhD student, Alemayehu traveled with his professor to Daga Estefanos, one of the remote island monasteries on Lake Tana. The forest was dense, and in the course of wandering around, they became lost. His professor was from the Netherlands, so they were speaking English. Suddenly a guy appeared in dirty clothes and long dreads. Alemayehu and his professor carried on their conversation in English, discussing which path to take, until finally the hermit told them which way to go. It was clear he had understood their entire conversation. There are some very educated people who live as hermits, Alemayehu explained: pilots, doctors—professionals who at a certain point say, I’ve had enough; I’m going to live as a hermit.

There are different hierarchies among hermits, Alemayehu explained. “Only the holiest of them, if they are given this gift from God, are allowed to become invisible. They can chose when and to whom they will reveal themselves. Some of them disappear forever.”

“That sounds like something out of the Acts of the Apostles,” I said. I was thinking of the miraculous stories of Jesus’s early disciples who spoke in tongues and healed the sick.

“Exactly. That kind of thing can really happen in Ethiopia, especially in these remote areas of the forest. I can’t prove it. It’s a feeling.”

Of the early anchorites in the deserts of fourth-century Egypt, historian Benedicta Ward wrote, “the monks were like trees, purifying the atmosphere by their presence.”

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

Most church forests claim only a handful of hermits. And then there is Waldeba.

When Alemayehu described Waldeba, a vast forest in the far northwest of the country on the border with Sudan, I was transfixed. He estimated this old-growth forest to be ninety thousand hectares in size, and it was inhabited almost entirely by hermits. The drive was far. One had to walk through the forest for two days just to reach the hermit dwellings and, even then, spend several days in silence and prayer to earn the hermits’ trust before you could speak.

Later I was talking with one of the priests when he mentioned Waldeba, and his own strange encounter there. As a young man he had made a pilgrimage to fast and pray—praying and fasting, he explained, were “the tools to live in the house of God”—and there in the forests of Waldeba he had a vision. Before him stood one of the hermits. His dreadlocks hung down to his ankles. The pilgrim knelt and waited for the hermit to speak, and when he spoke he told the young man to go out and preach the Word. This happened many years ago, he explained. He was old now and had happily lived out his life following the hermit’s advice.

When the priest finished his story, I asked for his blessing. He extended his wooden cross and touched my forehead three times. Then he rubbed his hands on my cheeks, neck, and forehead, intoning words of blessing and blowing his breath over me. I welcomed it for what it was: a gift, a transference, a sharing of the ancient breath he himself had received in the forests of Waldeba.

The Inner Wall

The forest path widened; the light grew stronger. We were approaching a clearing with another stone barrier: the inner wall. Beyond the wall the church’s tin roof reflected the late morning sun.

The inner wall looked like a much older version of the outer wall: of shoulder height, three to four feet in thickness, built of volcanic basalt stones dry stacked many centuries ago by an expert mason. The only difference were the massive roots that had grown up in between the stones. Here it was again, the easy intertwining of the arboreal and the human.

Given our proximity to the tabot, the holiest place in the Ethiopian Orthodox imagination, I recalled what Alemayehu told me when I asked about distance. I had wanted to know how far outward the tabot’s sanctity extended. It depends, he said, on what the community and the priests agree on. The moment they decide that this will be a church compound, they hold a ceremony to sanctify it.

“It’s not the distance that matters,” he said. “It’s the belongingness and blessing.”

“So potentially you could have a church forest that was hundreds, even thousands, of hectares?” I asked.

“Yes. We have some that are three hundred hectares already. And then of course there is Waldeba.”

Why was the Ethiopian Orthodox Church needed to protect these forests? Why not a national park?

“I’ve seen forests transferred to the state that were destroyed overnight,” he said. “It’s only because of the patronage and blessing of the church that these forests have survived. It’s their passion, their religious commitment to safeguard them. Why are we here?” he looked around, gesturing to the inner wall, the church, the forest. “Because it’s the only place we still have forests. We scientists are highly indebted. Now after protecting the forest for so many centuries, the churches need us. We scientists can help.”

I followed Alemayehu around the inner wall. We passed a rough wooden structure, inside of which were several grave markers. The church forest, I learned, also serves as a place of burial. There are no private cemeteries here, Alemayehu explained. Everyone who is an Orthodox Christian is entitled to be buried in a church forest. It is here they are baptized, and it is here they are buried. “To us the church forest is the beginning and the end,” he said, “the Alpha and Omega. The eternity.”

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

The Church

Slowly, one by one, the white-robed priests entered the inner courtyard. Each paused at the threshold to cross himself. The building itself, like nearly every other church in Ethiopia, was round; on its tin roof sat two solar panels.

The roof reminded me of a church I’d visited several days before on the Zege Peninsula at Lake Tana, a monastery called Abuna Maryam, or “Saint Mary,” on whose rooftop were displayed seven large eggs: ostrich eggs, one of the priests explained. Both male and female ostriches take care of their eggs, he said, just like God always takes care of us. If God leaves us, we spoil.

When everyone was gathered in the courtyard of Zajor, the speeches began. I couldn’t find Tegistu to translate, so I took off my shoes, as is the custom, and wandered into the church’s dark interior.

I was greeted by the smell of dust, centuries of dust, followed by aromas of frankincense, wood, and sweat. As my eyes adjusted to the dark interior, the human imprint was everywhere visible. Wattle and daub walls shaped by hand. Twin rough-hewn doors, fifteen feet tall, carved by hatchets from a single slab of sycamore. Door frames and support beams hewn from juniper, the tree on which Jesus hung, each post covered in a dark patina rubbed smooth by centuries of sebaceous oils passed from hands, lips, foreheads.

I touched a door lintel, crossed myself, and stepped across the threshold. This was the qine mehelet, the chanting place. A circular inner wall rose before me, perhaps twenty feet in height, painted floor to ceiling with elaborate icons. The wall seemed to contain every major biblical story: The expulsion from Eden. The Flood. Jesus healing the leper. The Tree of Life.

During the centuries when most people were illiterate, icons served to teach the biblical stories. The paintings, most from the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, were made from natural dyes taken from local plants. Other than the tin roof and solar panels, all the materials for the church came from this place. In these icons was a forest transformed, the trees and roots and pollen all having passed through the fires of human imagination, while still retaining their sylvan imprint.

I heard singing. A priest walked toward me, reaching into his white robe for his flip phone. His ringtone sang in Geez, the ancient liturgical language known only to priests. Tegistu had found me, and I asked him to translate. It was a song composed by Saint Yared, who lived in Axum in the sixth century and who is credited with inventing the sacred music tradition of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. This song, Tegistu said, recounted Jesus’s words to the women who wailed for him as he carried his cross of juniper toward Golgotha. “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me,” he told them, “but weep for yourselves and for your children.” Suddenly, I felt the centuries fall away. Here were the words of a first-century rabbi transcribed by the writer of Luke’s gospel, picked up five centuries later by an Ethiopian hymn writer who translated Koine Greek into Geez, the words dwelling in that language for the next thousand years only to appear on this day in the forest of Zajor, amplified through a piece of technology made in China, then refracted from Geez to Amharic to English; and through that convoluted matrix, I could still feel the raw emotion of a man condemned to hang on a tree, speaking a word of comfort to his followers.

I walked the concentric circle of the chanting place, looking at each icon in turn, until I came to the Flood story. I thought again of Meg’s description of the church as Noah’s ark. Until the waters receded and the first green leaves emerged, all the creatures of the world were sheltered there. Ethiopian Orthodox Christians also see the church as a symbol of the Garden of Eden. The Ark and the Garden. Two potent metaphors. How very different to think of the church this way, instead of, say, the City on the Hill, that beleaguered fortress image to which so many American Christians still cling, as if faith were a redoubt in need of defending from the pagan hordes. How much more inviting to perceive the church as refuge, a place where all life, not just human life, is preserved and honored by God.

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

I had come full circle. To my left lay the main entrance, to my right another doorway leading deeper into the interior. Beyond the door on my right lay the meqdes, where people receive communion, and beyond that the qidduse qiddusan, the Holy of Holies, where the tabot sat quietly in the darkness.

I paused.

Here at the completion of my circumambulation, I no longer felt drawn to the center. The Holy of Holies was forbidden, of course, so there was only so far I could travel. But I mean something else. After walking through the majestic cathedral of trees, full of holy figs and junipers and flowering dongas, the actual church building felt somehow anti-climactic. I had a sense that this small, round structure served not so much as the center of attention, but merely as a fixed node for the imagination. In our own journey to the interior, we need these points of reference on which to build our personal and social imaginaries, but only as temporary stops. For those following a mystical itinerary, as my Ethiopian counterparts were teaching me, the real action will always lie beyond reach, just around the next path, another way in which forests are an analogue for the spiritual journey. The more we learn, the more vast and inscrutable our inner and outer worlds become. Ch’aka: forest, wild, mystery.

That day at Zajor, I needed to follow the path back out into the forest, where trees were offering their hidden intercessions, telling the air things the world needed to hear, out there where hermits sat under those same trees tapping into the Great Mind of the universe, bringing back secret reports of mercy.

I left the church’s somber, dusty interior and stepped out into a courtyard full of dappled sunlight. A forest breeze touched my cheek. I inhaled deeply.

The priests were already on their way to the next stop, a nearby clearing in the forest. It was time to eat.

The Communion Feast

Aromas of cooking fire and boiled meat wafted through the trees. I followed the priestly entourage down a small path, the smells growing more pungent. We emerged into a clearing. Several rough-hewn wooden benches, a series of woven mats, and two plastic chairs were arranged in a circle. Alemayehu and Meg were offered the plastic chairs, the seats of honor. The elderly priests sat on the benches, and the rest of us took the ground.

I asked Tegistu about the beautiful tree in the center of the clearing. Teclea nobilis, it’s called, named after a saint because it was found in his monastery in the fourteenth century. Beneath this tree sat the elderly priest with the ornate staff.

Two teenage boys entered the clearing lugging a plastic five-gallon jerry can. Cups were produced, rounds from the jerry can were poured. The drink was tella, a type of beer made of finger millet and maize. Then came bottles of arake, a distilled spirit made from finger millet. I passed on the tella, which tasted like watery sourdough starter, but the arake was a different story. Smoky, earthy, and vegetative, it reminded me of a fine Oaxacan mezcal.

Plates of injera appeared, then shiro, a chickpea sauce, then the main course, which I’d smelled on the way in. The meat was carried by two boys, hauled in a massive plastic tub. Lamb or goat, I couldn’t tell, but it was savory and tender. This was followed by my favorite dish, warm goat yogurt, which still bore a whiff of the cooking fire. We ate. We sipped tella and arake. We communed. Inside the church building they served bread and wine, but here in the forest clearing, injera and tella had become the living sacrament.

More speeches began. I didn’t catch everything—Tegistu’s translation was coming in between bites—but I heard something about King Solomon, how Zajor hosted the Ark of the Covenant, and how in the centuries ever since, Zajor had been known as a place of hospitality. Perhaps five or six different priests rose to express their gratitude to Alemayehu for his help building the conservation walls, and to Meg for raising the funds.

When the speeches were over, the group slowly and amiably made preparations to return to the bus. The afternoon was lengthening, and there were other church forests to visit.

Photo by Jeremy Seifert

The Holy of Holies

The entourage filed out of the clearing until only a few of us were left. Tegistu pointed out a Rüppell’s vulture high up on a juniper branch, and above him a pair of nesting tawny eagles. A faint breath of cool air blew through the clearing. Zajor had cast its spell. I didn’t want to leave.

Under the beautiful tree sat the priest with the ornate staff, the elder who organized the building of Zajor’s wall, of whom Alemayehu expressed his deep fondness. When he noticed me, he smiled and beckoned, as if he wanted to tell me something. I approached. Normally I would have started in on my questions, the kind of journalistic softballs I’d been asking of all the priests I met and which started to seem less and less like meaningful questions, such as tell me about the relationship between the forest and the church or what do trees mean to you; but these no longer seemed like the right questions. I was realizing that I could spend a lifetime in this one forest alone and still remain ignorant of its mysteries. I did what I had done a hundred times on this trip when meeting a priest: I crossed my arms over my chest, bowed low, and asked for his blessing.

He nodded and held out his wooden cross for me to venerate. He spoke his blessing and I stood to take my leave, but then he placed his hand on my right forearm. Did I have a family? He asked me to write my wife’s name, and the names of my three sons. I jotted their names on a torn piece of notebook paper. He would pray for us every day, he told me. Slowly, imperfectly, he read aloud the names—first my wife, then each of my three sons—and as he read, I felt something inside of me open. Whether it was the prolonged absence from my family or the accumulation of awe or something more, I cannot say, but as I heard this man’s sonorous voice, I imagined him speaking my loved ones’ names in the days and months to come, interceding for my family just as he interceded for countless others, for the trees, for the animals, for all life, and in that moment I felt myself part of the invisible communion of saints, a family not bound by race or creed or geography, or even physical form.

An invisible weight pressed upon my shoulders. I dropped to my knees and began to weep, overcome by this man’s kindness, by the sharp awareness that our lives were not bound by space or time, but were strangely intertwined. It seemed a long time before I was able to stand.

When I arrived back at the Land Rover, the others had been waiting. I couldn’t begin to articulate the reasons for my delay. Later on the drive we were nearing Bahir Dar, our home base, with Lake Tana in the distance. Between us and the water, banking over a dark green marsh, a flock of Eurasian cranes turned and began their long, slow descent.

What I’d experienced there in the forest clearing at Zajor was beyond my ability to describe, so I simply told Alemayehu I’d had a powerful encounter with the elderly priest.

“He is a very holy man,” Alemayehu said. He was quiet for a time. “He’s one of the guys who is in between. I am sure one day he will disappear.”

All Will Come Again into Its Strength

When Alemayehu dreams of the future, of the Ethiopian highlands he hopes to see as an old man, he sees a land covered again with forest. He’s aiming for forty percent. By then church forests will not only be conserved, they will have grown and spread. There are already church forests dotted roughly every three kilometers across the highlands. If every church forest expanded, eventually some of them would begin to join—like merging nuclei. That’s one of Alemayehu’s three models for realizing his dream.

The second model is to plant the rivers and streams. If you read the landscape carefully, he says, you will notice that church forests are already connected by waterways. If those riparian areas could be planted in trees up to ten meters on either side of the bank, you would have corridors along which seeds and germplasm could flow. Rivers of trees. The third model he calls area enclosure: fencing off land from human or animal disturbance, and simply letting it regenerate. If left alone, forests will heal themselves.

Listening to Alemayehu, it’s easy to feel that the dream is within reach. Already he’s been advocating these three models to NGOs. Working through the TREE foundation, he and Meg hope to raise a quarter million dollars to conserve the remaining twenty-four high-priority forests, a tiny amount by international conservation standards. “Less than a new Jaguar with all the add-ons,” Meg said.

Two of the fourteen church forests have already expanded their walls. When Alemayehu told me that, I had to ask him to say it a second time. Yes, he said, they simply picked up the stones and moved the wall farther out, growing the forest by several hectares. And already, in the protected church forests, he’s seen the spread of germplasm. Here he grew animated. “Trees can jump!” he said. “The wall does not prevent them.”

When I think of Alemayehu’s dream, it seems that it’s not his dream so much as it is the land dreaming through him, or God dreaming through the land, which then rises up in the mind of one man and spreads, a dream of what the land wants to become, and will be again.

I’m reminded of these lines from Ranier Maria Rilke, from his Book of Pilgrimage:

All will come again into its strength:

the fields undivided, the waters undammed,

the trees towering and the walls built low.

And in the valleys, people as strong

and varied as the land.1

This is a story about trees and hermits, which is to say it is a story about those unseen forces that undergird our lives, forces to which we pay scant attention but whose quiet power lives and breathes for us, sustaining us, waiting to rise up within us and find expression.

Religious traditions demonstrate our very human need to locate our spiritual yearnings in the things of this world—a wall of stone, a piece of bread, a sip of wine. Perhaps our time calls us to extend that yearning to the trees. To find God not only in the bread and wine, but in the bark and branch, the soil and mycelium. To notice the intercessory work of forests, breathing their invisible sighs from every copse, stand, and canopy. If we lose that, we lose not only shelter, medicine, the source of springs, and sequestered carbon. We lose part of our imaginations. Without forests, where will our creativity, compassion, and longing—those invisible, reclusive parts of ourselves—find a home?

Forests like Zhara and Zajor offer us a totemic image that stretches across the centuries, a pattern of caretaking that can be repeated wherever our forests of belief, and actual forests—or deserts or estuaries or backyard gardens—meet. It is a vision not of transcendence, but of immanence, of finding God again, and thereby finding our deepest selves, in the living world.

It is an inner vision that ripples outward, stretching our awareness of the holy in ever-expanding circles until the whole world fits inside.

I remember what Alemayehu told me that day at Zajor, as we stood beside the grave markers. “I always contemplate that this is my end,” he said. “This is where my body will live forever. I will become part of a tree. Ashes to ashes. Dust to dust. The eternity.”

- “Alles wird wieder gross…/All will come again into its strength,” from Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God, by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy, translation copyright © 1996 by Anita Barrows and Joanna Macy. Used by permission of Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

The Church Forests of Ethiopia

Over the past century, farming and the needs of a growing population have replaced nearly all of Ethiopia’s old-growth forests with agricultural fields. This film tells the story of the country’s Church Forests–pockets of lush biodiversity that are protected by hundreds of churches scattered like emerald pearls across a brown sea of farm fields.