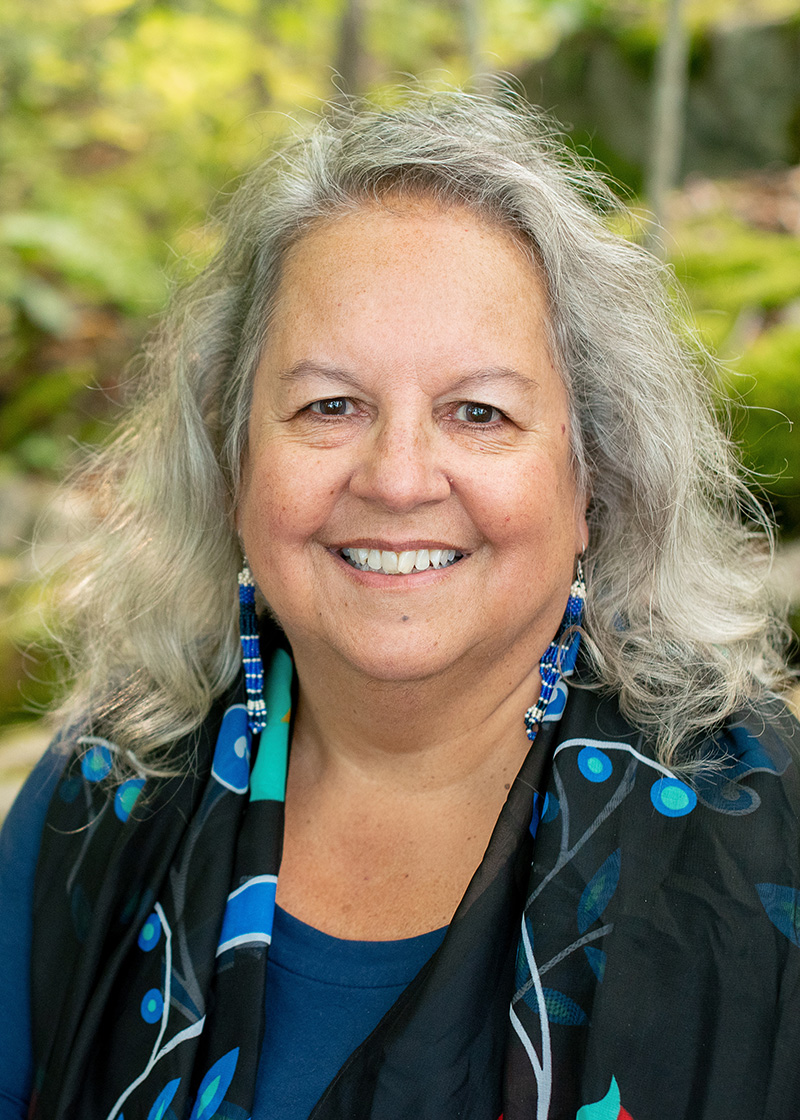

adam amir is a Vancouver-based filmmaker who works for the Tahltan Central Government of the Tahltan First Nation in Northwest BC, Canada. His work for Tahltan has featured across international media, and he has also filmed in Navajo, Central Asia, the Congo, and elsewhere. adam’s image-work has appeared in Nature, The Narwhal, and The New Yorker, and the subjects he’s covered range from gorilla totems and taboos, to wolves and justice in Tajikistan, and methods for decolonizing conservation. His films include Nzhu Jimangemi (The Gorilla’s Wife), which won the Jean Rouch Award for exceptional collaborative filmmaking; and Walking Before Walking, which featured in The New Yorker.

What’s a season if you’ve only circled the sun a few times? And can’t really remember what it was like at this time last year?

A young child’s sense of time must be overwhelmingly abstract. Time is the ever-present now. While the rhythms and routines mark the daily cycle—breakfast and bedtime, bathtime and naptime—beyond a day, the cycles become too vast to comprehend. Our four-year-old still doesn’t understand what a week is, let alone a month or the phases of the moon. “Why is it a weekend?” he asks, as we head to the forest instead of daycare.

Seasons mark time and in their distinct elements make it tangible. Akin to how you might walk the land to learn it, you try to catch time in the act of passing, seeking understanding. Seasonal practices allow you to enter time as if it were space. By providing structure and consistency, practices create moments. We were here at this time last year, do you remember? See the buds? They’re almost here again.

To take our kid into the seasons, I try to show him time as a space, a place we can go. When he can’t remember this time last year, his mother and I call up stories and images. We talk about what happened last year, and what might come this year. This may be one reason I document our practices, to create a record for reference.

We have a name, place, and time for each of our seasonal practices. And we have more than four. The practices reflect cycles in the land where we live, and orient us to the ephemeral—the shifting, changing, only-here-for-so-long.

This is how I try to teach our kid where we live, and figure it out for myself. This is how we learn the land, in space and time.

Snow Line

Wherever snow lies, we can sense the season, but we search for snow line—the exact place where the world turns white.

When the days are short in the temperate rainforest, there is a line through the Doug firs and cedar. A curtain that marks the threshold between worlds of white and green. On the way up, the white feels right, like mountains should be capped with snow, the world growing brighter as you go higher. But coming down, it’s the intensity of the color, the too-green of the rainforest in the rainy season, that jolts you every time. After all the white, the almost monochrome of winter mimicking moonlight, to enter such color feels impossible. A hallucination. How can the very same mountain, at once, be so green?

This time of year, we climb to the snow line of a favorite mountain, continue into the snow, and then come back down again, to feel this sensation. Our seasonal practices are this simple.

Meeting the Migration

When animals wash across the land, we go to meet the migration. We camp at stopover sites, nestled between swaths of soybeans, to watch sandhill cranes and snow geese fill the sky. We wade into marshlands and stumble onto swans, floating off a delta island where the river meets the sea. We ferry to gulf islands to see the sea explode with all who come to feast on herring, streaks of deep-green seawater turning tropical turquoise in the haze of eggs. A few seasons later, we walk up rivers, greeting chinook, then pink, sockeye, chum, and finally zombie coho spawning out in the snow.

Barry Lopez describes migration as the land breathing. He sees it as one great breath, the light and animals drawn north, inhaled, held, then released south with an exhale. With your face in the wind of wing beats, in the pulsing of a thousand dunlins, in the bursts and blasts of hundreds of snow geese, it can feel like the land is breathing before you.

To the child, you can try to explain how far these birds have traveled, and how much farther they will go. What they’ll eat, where they’ll sleep, and how they find their way. You can try to describe how the salmon’s physiology changes as they leave the river for the sea, their years in the ocean, how they’ve come home to die. But the facts only make comprehension even harder. How can this be happening? All these geese are on their way from California to Chukotka?

The sense of bewilderment that migrating wildlife can bring offers a way “of merging with other systems of space and time,” as Jack Halberstam explains. The animals arrive and everything changes. The same place is a different world.

This practice is about letting wildness bewilder us.

Sakura

We live on unceded land, shared by the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, whose seasonal sites and practices overlap here. The relationship between these Nations and their land sets the tone of this place. When we are welcomed at events, hear the songs, and encounter the unique aesthetic that emerged from this region; when we learn the proper names of our streams and mountains, seashores and great volcano, we feel more connected here.

The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh have more than a dozen names for the seasons, including temlháwt’ (herring time), tem tsá7tskay (plant shoot time), and ten eshcháwm (salmon spawning). Hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ (the language spoken by xwməθkwəy̓əm and səlilwətaɬ) includes as many, such as tem ćəm̓əx (herring roe), təm liĺə (salmonberry), and təmθə́qəy̓ (sockeye) seasons. Nearby, across the Salish Sea and among the islands, W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) seasons include Pexsisen (blossoming), Penáwen (harvest seaweed), and a series of salmon seasons: Ćenŧeki, Ćenhenen, Ćentáwen, and Ćenqolew. The Sockeye returns to Earth. The Humpback (Pink) returns. The Coho. The Dog (Chum) Salmon.

To learn how to live here, my partner and I look to First Nations friends and co-workers: artists and authors, in particular, among the many nations of the Stó:lō, the Salish Sea, the temperate rainforest stretching from the Klamath to the Alsek. We read their writing and watch their films, attend their events and shows, and their ideas linger. Years ago, we went to see a Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun exhibit, in which he was calling for the renaming of British Columbia, noting how changing the name “will change our idea of where we are.” Ever since, I am careful in how I refer to our mountains, rivers, and sea, our volcano, spots, and places, especially when speaking of them with the kid.

I work for a Nation in the north and get to drop in on culture camps and fish camps, visit with gathered families, join hunts, and help pack out meat. I learn not only what to do on the land (and when), but how to behave as we do so. I get so many ideas from colleagues and friends, observing what they do, how they practice. I note how they change their practices too: for example, in response to communal concern for chinook or caribou.

But no matter how much my partner and I learn, as immigrants we carry cultures from afar. The traditions and practices we learned as children do not connect us to the land here, or its seasons, in the same way. We want to share our traditions with our children—and not be the ones to cleave them from their ancestors—but what sense do these distant practices make here?

We’re raising our children over a thousand miles from where each of us grew up, and farther from the lands of our great-grandparents. And all around us, many others are too. Their ways become part of living here as well. Together, we start to share each other’s seasonal practices. This is another way to learn to live here. To remember, while also adapting.

This practice is about learning the cultures of the land, and of each other. By attending seasonal festivals, and by sitting with the sakura, we honor practices outside our own.

Plucking as Prayer

Two years ago, snow line hung higher than ever. Our snowpack, the source of our water, was the lowest on record. The sakura seemed confused, blooming out of sync. Old trees lost large branches to unusually heavy, late, wet snows.

Four years ago, a week after the kid turned one, a heat dome descended upon us. Over twelve days, the heat killed over six hundred people. Most were elderly, and lived alone. All but a dozen died inside. Biologists at the University of British Columbia estimate a billion sea creatures perished: mussels, clams, and barnacles boiled alive as the dome refused to lift. Mobile and fortunate, we fled to a mountain river one day, tidal flats the next, seeking sanctuary from the heat. The sense of relative climate security we’d developed, nestled on our wet, temperate coast, instantly shattered. We came home and suffocated. Lingering in our memory is the feeling of heat that would not abate, even in the evening. How our bodies would not cool down, could not cool down, even at night. We found relief in the cold mountain water, and the slight sea breeze, but we don’t live or work there. We had to come home, and home was a hot you could not escape.

Where others have traditions to teach, classes for their children, very old stories to tell, I have but a feeling.

This time of year, it’s hard not to think of the heat dome. Or the wildfire smoke the years before and after. But this season can be glorious too. Rainy season, snow season, sky season, even salmon season, are all slippery and unpredictable. Not so with berry season. We notice as soon as the berry buds arrive, then return day after day in anticipation of the first fruit. Once the salmonberries show up, the rest follow fast. Thimbleberries, strawberries, salal, blackberries; red and purple and baby blue huckleberries, which taste a bit like banana. There may be no practice the kid enjoys more, no season easier to celebrate.

The practice is so simple: pick, pluck, pop it in your mouth. Taste the wild land, the short season. The best part may be how each berry tastes slightly different, distinct from the berry beside it, from itself if you were to pick it next week; how, in high mountain meadows, you literally wade through berry bushes, swimming in sweetness.

This practice is about intimacy with the land. Berry season is when you take it into the body.

A SHARED LANGUAGE

Many sense the mystical in the mountains. Trying to get the kid to feel the tingle too, you step into the numinousness, hoping the kid will follow, but only fall further in.

Watch a young child amble along an intertidal island, even as the shimmering sea slips in to reclaim it. The child, oblivious to the beauty, kneels to poke at a periwinkle, turns over a twisting mudflat snail shell in search of a hermit crab. At the edge of awe and aww is ecstasy. The sole sensation is of love, for the world, for the child, for how they inhabit each other.

If you must understand something to teach it, how do you pass on that which you lack the language to understand? Where others have traditions to teach, classes for their children, very old stories to tell, I have but a feeling. A sense of the spirits or souls of the land. I am reluctant to try and name any of this. But without names, unable to articulate this sense, how do I share it with our children?

The purpose of our practices is to create the time and space where the kids just might sense something too, in part through the way the seasonal shifts make the land feel so very alive. Our practices ask only this: go meet the season. We pray through pilgrimage, to snow line, to snow geese; to surreal sakura and thousand-year-old cedars; to salmonberries and salmon streams. This is how I learned to love the land, the seasons, the world. I hope, through these practices, our children come to love them too.

By returning to the same places at the same times each year—marshlands in the migration, sidewalks in the sakura, rainforests in the rain—our practices mature into rituals. But we lack community, a shared language. I worry that when our children are grown, they won’t have others to practice with. Even among those who love the land as they do, they may not recognize each other’s rituals.

I present our practices here in hope that others might do the same, and together we might develop prayers and practices our children someday share.

CREDITS

Featuring Rumi Amir

Written, Narrated & Directed by adam amir

Produced by adam amir & Noal Amir

Executive Producer Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee

Director of Photography adam amir

Edited by adam amir

Original Music Composed & Performed by Phillip Hermans

Vocals Performed by Riga Amir

Sound Design & Mix by Phillip Hermans

Additional Sound Recording by Sunny Tseng

Dall’s Porpoise Footage by Dr. Eric Keen, courtesy of Luke Padgett