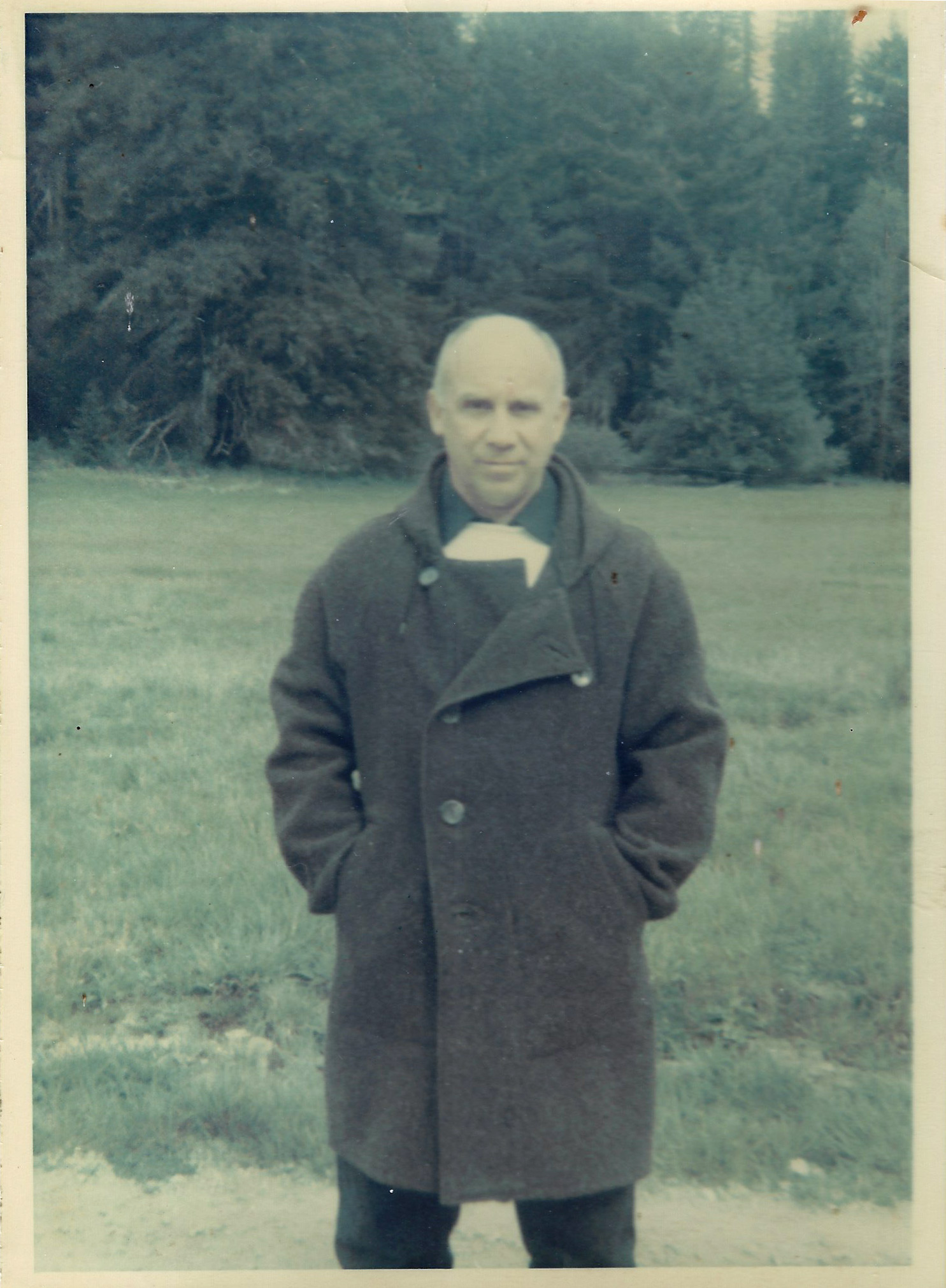

Fred Bahnson is the author of Soil and Sacrament, and his essays have appeared in Harper’s, The Sun, Orion, Oxford American, and Best American Spiritual Writing. His essay “On the Road with Thomas Merton,” originally published in Emergence Magazine, was selected by Robert MacFarlane for Best American Travel Writing 2020. He is a recipient of a W.K. Kellogg Food and Society Fellowship, a North Carolina Artist Fellowship, and a Terry Tempest Williams Fellowship for Land and Justice at the Mesa Refuge. He lives with his family in southwestern Montana.

Jeremy Seifert is an award-winning film director, cinematographer, and editor whose documentaries have premiered at Sundance, Berlinale, Hot Docs, Tribeca, and AFI DOCS. His feature films include The Devil We Know, co-directed with Stephanie Soechtig; and the award-winning documentaries GMO OMG and DIVE! Living Off America’s Waste. His short documentary for Emergence, The Church Forests of Ethiopia, premiered on New York Times Op-Docs. Jeremy is a frequent contributor to Emergence Magazine.

In May 1968, Christian mystic Thomas Merton undertook a pilgrimage to the American West. Fifty years later, filmmaker Jeremy Seifert and writer Fred Bahnson set out to follow Merton’s path, retracing the monk’s journey across the landscape. Amid stunning backdrops of ocean, redwood, and canyon, the film features the faces and voices of people Merton encountered. The essay offers a more intimate meditation on Merton’s life and the relevance of the spiritual journey today.

I. Woods

On the flight from San Francisco to Eureka, he looked out the window and caught his first sight of them: redwoods.

Even from the air, the trees appeared enormous. To the north, Lassen Peak and Mount Shasta rose like great silent Mexican gods, white and solemn. When he looked down again, the trees were gone. Entire hillsides slashed into, ravaged, stripped.

Life seemed to be unraveling everywhere that year. The date was May 6, 1968. Vietnam was in full swing, and King had been assassinated just one month earlier. Ever increasing frenzy, tension, explosiveness of this country, he wrote in his journal.

Thomas Merton was perhaps the most important Christian mystic of the twentieth century. For the past twenty-six years, he had lived as a Trappist monk at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, and for the past three he had lived in a cinder-block hermitage in the woods. I am accused of living in the woods like Thoreau instead of in the desert like St. John the Baptist, he wrote to a friend. Whatever else can be said about Merton, and much has been said, one thing is certain: he was a monk who loved trees. One might say I had decided to marry the silence of the forest, he wrote. The sweet dark warmth of the whole world will have to be my wife. Out of the heart of that dark warmth comes the secret that is heard only in silence … Perhaps I have an obligation to preserve the stillness, the silence, the poverty, the virginal point of pure nothingness which is at the center of all other loves.

He had been searching for that center his whole life.

Le point vierge, he called it.

Now, in May 1968, he was beginning a three-week journey out west in search of a new hermitage site. He was on his way first to Redwoods Monastery in Whitethorn, California, then on to the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in Abiquiu, New Mexico. During a brief stop in San Francisco, he would spend the night at City Lights Books, talking poetry late into the night with Beat poet and City Lights co-founder Lawrence Ferlinghetti. This monk who wed the silence of the forest was also a gregarious lover of people, which is exactly why he needed to flee their presence. He yearned for the kind of deep solitude where he could shed his public persona and live for God alone. Perhaps he would find it among the California redwoods, along the Lost Coast, or in New Mexico’s Chama River Canyon.

Before the flight, he sat at the airport bar in San Francisco and drank two daiquiris. Impression of relaxation, he wrote. Ever the wide-awake monk, he couldn’t even enjoy a decent buzz, only the distanced impression of such, yet even in the airport bar, he was recovering something of himself that had long been lost.

On the flight into Eureka, he jotted down notes for talks he would give to the nuns at Redwoods Monastery, a young abbey nestled among trees that were already saplings by the time Jesus was born. He copied dense philosophical quotes by Hegel, Unamuno, and Sartre, but in his journal such abstract quotes soon gave way to the language of direct encounter, as if once his hand touched redwood bark, those erstwhile forests of philosophical thought quickly lost stature, dwarfed by comparison.

When he stepped off the plane in Eureka, Sister Leslie complimented him on his beret. They bought a couple cans of beer and hit the road, driving south along the Eel River. From his view in the passenger seat, he took in the passing world. Everything from the big ferns at the base of the trees, the dense undergrowth, the long enormous shafts towering endlessly in shadow penetrated here and there by light.… The worshipful cold spring light on the sandbanks of Eel River, the immense silent redwoods.

Like a cathedral, he wrote.

On a Wednesday evening in late May, fifty years later, I step into the cathedral of trees surrounding Redwoods Monastery and enter the ongoing stream of silence.

I’m following the itinerary Merton described in his journal from that 1968 western journey, posthumously published as Woods, Shore, Desert. “It’s one of the world’s truly interesting journals,” Annie Dillard wrote of the book. Merton’s photographs from that journey, a selection of which appear in Woods, Shore, Desert, depict the surf crashing on Big Sur, a clump of ferns beneath a redwood, a beach empty of all but driftwood and fog. After twenty-six years of the inward journey, Merton was finding a new bearing in the American landscape itself. I dream every night of the West, he wrote upon his return.

I was curious why he made the journey at all. For years he had longed to live in a hermitage in the woods on the grounds at Gethsemani Abbey, until finally his abbot granted his request. What more was he still seeking?

What am I seeking? Here at the beginning of my journey following Merton’s steps, I wonder why, even in the midst of a flourishing family life, I still feel pulled toward silence and solitude, or why I can’t seem to shake this spiritual restlessness that has driven me most of my life, a propulsive desire to seek out the horizon. I feel those same yearnings in Merton’s writings. But my connection to him goes deeper still.

Merton was an orphan. His mother died when he was six, his father when he was sixteen. His parents’ deaths marked him in profound ways, but in his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, the most harrowing scenes from his childhood occur during the three years he spent at a French boarding school. Thomas was eleven when he was sent to the school. Once there, he pleaded in vain with his father to let him come home. For the next three years, Lycée Ingres, a place full of “some diabolical spirit of cruelty and viciousness and obscenity and blasphemy and envy and hatred that banded [the children] together against all goodness and against one another,” became his home. When young Thomas lay awake at night “in the huge dark dormitory,” he knew for the first time in his life “the pangs of desolation and emptiness and abandonment.”

When I was ten years old, one year shy of Merton’s age when he went to boarding school, my parents sent me to a place with diabolical spirits of its own. They moved our family to Nigeria so they could volunteer as medical missionaries, and I was sent to a mission boarding school. For the next three years, I lived in a dorm with twenty other children and a pair of adult caretakers who gave us food and gave us shelter but did not give us love. Neglect crept through the halls of our dorm each night and entered our rooms, looking to devour any exposed piece of our young hearts, so the trick was to keep them hidden. I came to know those pangs of desolation and emptiness of which Merton spoke. Years later when I discovered his writings, I knew that I was not alone. I had joined the camaraderie of the abandoned.

I arrive at the abbey in time for compline, the last service of the day. As the nuns chant the Psalms, I look around the church and take my bearings. In place of pews, wooden benches stand along three walls together with a selection of zafus and zabutons. The monastery is Catholic, yet a Zen-like aesthetic is everywhere present, perhaps most pronounced in the center of the chapel, which remains empty. Into that center the day’s last light pours from clerestory windows high up in the ceiling. Along the chapel’s fourth wall, floor-to-ceiling windows reveal a single redwood tree beyond, a four-leader trunk whose girth must be close to thirty feet. On the concrete floor, a series of long cracks run the length of the building. Redwood roots, I learn from one of the sisters, pushing upward. The trees are lifting the entire monastery off the ground.

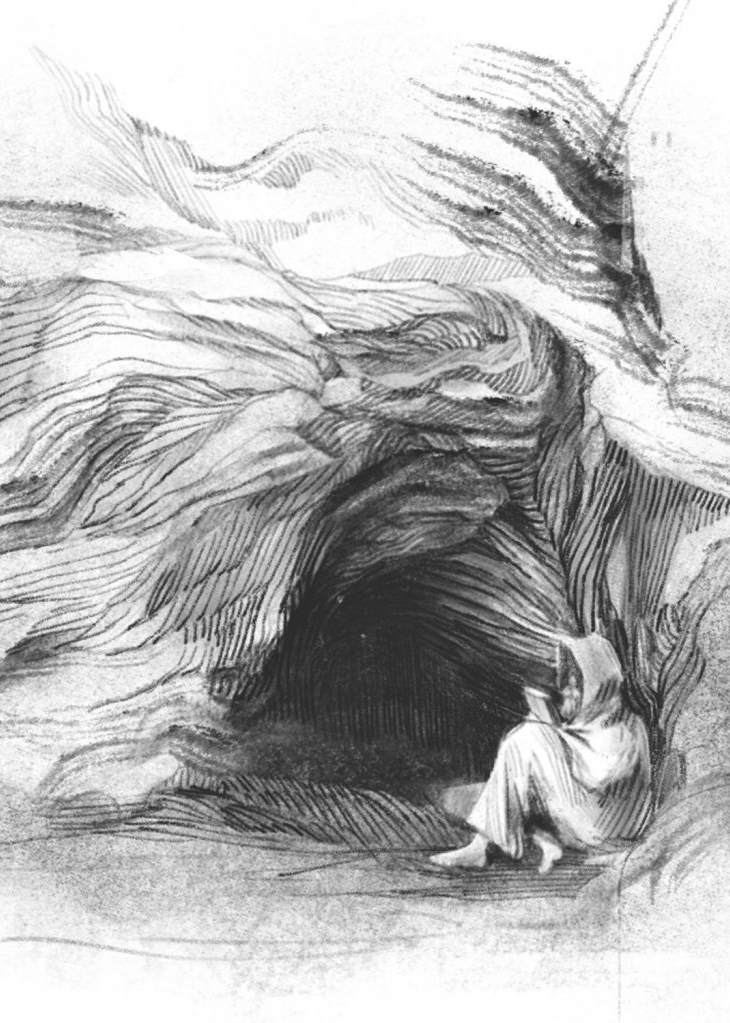

Northern California, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton1

The sisters of Redwoods Abbey are Trappists, also known as Cistercians of the Strict Observance, a worldwide Catholic monastic order of men and women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict and the Cistercian reforms of the eleventh century. Those reforms brought a return to simplicity, contemplative prayer, and silence. At a time when Christianity was taking a centuries-long detour into logic and rationalism, Cistercian monks were turning their attention inward, to the heart, where Jesus said we would find the kingdom of God.

The sisters chant the Psalms here in this chapel and in between chants they listen. Words are spoken or sung, but they are borrowed from silence and to silence they return. “The monastic journey is learning how to listen,” Sister Kathy, the abbess, tells me one day during my visit. “I don’t think we ever stop learning how to listen.” I experience it many times over the next five days—standing inside a circle of ancient redwoods across the Mattole River, sitting on a beach at nearby Needle Rock—but I find it first here among the sisters in their chapel of wood, steel, and concrete upheld by the roots of trees: a deep, welcoming silence.

Saint Ephraim the Syrian, a fourth-century monk, said to his brothers, “Good speech is silver, but silence is pure gold.”

After compline, Sister Karen, a nun from Bolivia, shows me to the guesthouse and assigns me the same room where Merton stayed. It looks unchanged since 1968. Cinder-block walls, a single bed, worn carpet, a desk and chair. I throw my bags down and walk to the patio, where I sit and watch the silent show unfolding out in the meadow. Two wild turkeys strut and preen. Beyond them a lone whitethorn bush stands in full bloom, its blossoms as white as the sisters’ cowls. When the fog settles, obscuring the remaining daylight, I turn in.

Can we redeem the desire to run from and turn it into a desire to run toward?

Unable to sleep, I sit at what I think of as Merton’s desk, a stack of his books in front of me, and reflect on why I’ve come.

As I confront the lingering feelings of exile and loneliness from my childhood, I find myself pining after what I call the geographical cure. Much more than simply an urge to travel, the geographical cure is the belief that whatever problems I’m facing at the moment will magically disappear if only I change zip codes for a day, a month, a lifetime. My awareness that the geographical cure is not a cure but an escapist fantasy makes it no less powerful an influence on my daily life.

So many of us are looking for escape routes these days: from depressing news cycles, from yet another school shooting, from climate change. Most days, though, my escapist fantasies are avoidance strategies for those mundane responsibilities of adult life. Still, I wonder: In our imaginative flights from reality, is there some original impulse that is worthy and true? Can we redeem the desire to run from and turn it into a desire to run toward? If so, toward what? I pick up my copy of Merton’s essay “From Pilgrimage to Crusade” and read the opening paragraph:

Man instinctively regards himself as a wanderer and wayfarer, and it is second nature for him to go on pilgrimage in search of a privileged and holy place, a center and source of indefectible life. This hope is built into his psychology, and whether he acts it out or simply dreams it, his heart seeks to return to a mythical source, a place of “origin,” the “home” where the ancestors came from, the mountain where the ancient fathers were in direct communication with heaven, the place of the creation of the world, paradise itself, with its sacred tree of life.

Merton’s essay describes two forking paths in the spiritual life, the choice between pilgrimage and its warped image, the crusade. But on another level we can see Merton working out his own restless desire for pilgrimage, why he felt unsettled at Gethsemani Abbey, why he needed to go in search of his own “center and source of indefectible life.” Did he really need to leave the monastery to find that center? Or was he, too, a victim of the geographical cure? Who were his models to help him discern the difference?

As I sit at Merton’s desk in the guesthouse of Redwoods Abbey, I want to believe that what brings me here is more than escapist fantasy. I find hope in Merton’s search, for it means that even a man who spent nearly three decades chipping away at his ego through prayer and stillness and contemplation was still a restless wanderer. Our yearning for paradise and its sacred tree of life may be part of our glorious human inheritance, but to help that yearning find shape and substance in our daily lives, we need guides.

Merton consciously sought out his own guides, most of whom had been dead for hundreds of years. “There are people one meets in books or in life whom one does not merely observe, meet, or know,” Merton wrote in Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander. “A deep resonance of one’s entire being is immediately set up with the entire being of the other.… Heart speaks to heart in the wholeness of the language of music; true friendship is a kind of singing.”

The early music that moved him most he found in Blake, Meister Eckhart, Ruysbroeck, Coomaraswamy, Dante, and he followed that melody line as it led him in later years to Sufism, Taoism, Zen, the Bhagavad Gita. But in the months leading up to his western journey in May 1968, the strongest singing came from the seventeenth-century Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō. Six months before Merton would depart for California, he read The Narrow Road to the Deep North, a series of travel sketches describing the pilgrimage Bashō undertook late in his life, a journey on foot over hundreds of miles. Opening himself to the elements, the aging poet carried little more than hat, staff, and satchel. Upon reading Bashō’s travel sketches, Merton wrote in his journal that he was completely shattered by them. One of the most beautiful books I have ever read in my life.… Seldom have I found a book to which I responded so totally.

When I came across this line in Merton’s journals, I felt as though I’d found the interpretive key to his journey. I immediately reread Bashō, hoping to find clues as to what Merton found so moving. “Days and months are travelers of eternity,” Bashō wrote. Like those who spend their lives traveling, he had “been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind—filled with a strong desire to wander.” Bashō is a connoisseur of simple pleasures found on a mountain pass or in one of the hermitages he encounters, or on the beach at Suma: “The scene excelled in loneliness and isolation at that season.”

Bashō walked north with no purpose other than his own unfulfilled longings: to see the full moon rise over the mountains of the Kashima Shrine, to see the pine tree of Aneha and the bridge of Odae, or to inhabit a scene like the one he describes in this haiku:

Tell me the loneliness

Of this deserted mountain,

The aged farmer

Digging wild potatoes.

I believe that what most drew Merton’s affection, more than any individual passage in Bashō, was the man himself, this aging poet who walked hundreds of miles through his native Japan in an act of self-abandonment. Like Merton, Bashō was a famous writer who, late in life, had wearied of his fame and who, after a lifetime of giving his words to others, needed to place himself before the Unsayable. Merton loved Bashō for the same reason he loved Russian icons or paleolithic cave paintings: they were all examples of pure seeing. In the final years leading up to his western journey, this desire for direct awareness became an increasing preoccupation for Merton. He was seeking bedrock. The undistilled center of our being in God. The pure drop.

At a castle ruins in the village of Ichikawa, Bashō wrote: “I felt as if I were in the presence of the ancients themselves.” He left those ruins and took a small boat to see the islands of Matsushima, which appeared to him “like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm in arm.… My pen strove in vain to equal this superb creation of divine artifice.”

Such is the power of literary influence. For much of our lives, the world spins past at too great a speed for us to notice, but sometimes we find a thread. We trace it back. Time and distance fall away. Suddenly we feel as if we are in the presence of the ancients themselves; we stand beside Merton as he stands beside Bashō on a deserted mountain in seventeenth-century Japan, all of us watching an aged farmer digging his wild potatoes. We feel the loneliness of that scene, yet we are not alone. We partake together. Heart speaks to heart across the centuries. This is the divine artifice at work and we strive to equal it: with our pens, with our lives.

At dawn it’s still raining. I awake to a chill in the air. I dress quickly, then realize I’ve slept through lauds and need not hurry. A brief stroll across the meadow, still shrouded in mist, brings me to the monastery. How pleasant on such a cold morning to find in the abbey kitchen a pot of hot coffee, cream from a local dairy, a mug, and a plate of oatmeal cookies, all of it left for me by one of the sisters. Monastic austerity, it seems, does not preclude cookies before breakfast.

I join the sisters for Mass, and afterward Sister Kathy invites me to sit and chat over more coffee and cookies. Sister Kathy arrived at the monastery in the early seventies, driving a green Triumph Spitfire convertible. When I ask what drew her to the monastic life, she tells me of a certain experience she had as a child, which she marks as the beginning of her spiritual quest. When she was six, her appendix ruptured. She nearly died. After two weeks in the hospital, Kathy arrived home. It was Easter Sunday, and while her large Italian family bustled around her, she remembers sitting in a chair, feet dangling over the edge, watching a single ray of sunlight spill through the window and illumine the space beneath her feet. Adults and siblings kept talking, oblivious to what she was sensing. In that moment she dropped beneath the noise and discovered God waiting for her. Here, she felt, was the life beyond life.

“That sounds like le point vierge,” I say.

“That phrase in Merton’s writings means a lot to me,” Kathy says. I ask her to elaborate. “The virginal point. It means pure, untouched, like the old-growth redwoods. He’s talking about an old-growth forest of the soul. It’s a profound metaphor for the spiritual life.”

I first discovered the phrase in Merton’s book Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, where he wrote:

At the center of our being is a point of nothingness which is untouched by sin and by illusion, a point of pure truth, a point or spark which belongs entirely to God, which is never at our disposal, from which God disposes of our lives, which is inaccessible to the fantasies of our own mind or the brutalities of our own will. This little point of nothingness and of absolute poverty is the pure glory of God in us.

Merton helped me articulate a belief I’d long suspected, that the core of our being is not rotten, as my Protestant upbringing had insisted, but is a place of untouched beauty and wholeness reserved for God alone, a place beyond ego that no evil can touch.

Merton borrowed the phrase le point vierge from Sufi scholar Louis Massignon, who borrowed the idea from the ninth-century Sufi Mansur al-Hallaj. As al-Hallaj wrote, “Our hearts, in their secrecy, are a virgin alone, where no dreamer’s dream penetrates—the heart where the presence of the Lord penetrates, there to be conceived.” As Kathy explains it, the idea is also deeply embedded in Cistercian tradition. Among Cistercians, you won’t find anyone banging on about original sin. Against the myth of “total depravity”—that small-minded theology invented by Calvinists in the sixteenth century to which an unfortunate number of American Protestants still cling—Cistercian anthropology is essentially positive. Which doesn’t imply a naïve attitude about human nature. Cistercians know of our innate propensity for self-delusion, which they speak of as “woundedness.” When we act out of our woundedness, we inflict collateral damage: on ourselves, on others, on the earth. Yet Cistercians believe that beyond the reach of our woundedness there remains a place in the depths of our being reserved for God alone.

Sister Kathy leans forward, her eyes ablaze. “We are stamped—stamped—with the image and likeness of God,” she says. “We are loved by the One who loved us first.”

Merton at Redwoods Monastery, May 1968.

“What can we gain by sailing to the moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves?”

Over the next several days, I fall into the rhythms of Cistercian life: prayer, silence, long walks in the forest. The meals—delicious vegetarian fare featuring local organic produce—are eaten in silence. Most communal work is also performed in silence so as to allow more time for prayer and contemplation. I spend much of my days here wandering through the redwoods. One morning I cross paths with Sister Veronique. Dressed in scarf, sweater, denim dress, and a pair of old leather hiking boots, she’s off on her morning walk, and I ask if I can join her.

It’s a lovely morning. The fog is lifting, and by the time we stroll over the Mattole River, the sun is coming down through the redwoods. Sister Veronique, age eighty-five, was one of the first nuns here at Redwoods Monastery, and perhaps because of her community’s isolation and the Cistercian practice of silence, her accent retains a lovely Flemish burl. She rolls her r’s, says “Very huud” to express approval, and speaks with much care and deliberation, occasionally stopping to take my arm and looking me in the eye. I sense that I’m in the presence of what early Christian monastics called an “amma,” a spiritual mentor whom pilgrims would seek for a word of counsel.

Sister Veronique leads me through a small wooden gate, then we walk down a narrow footpath in silence. We enter the cathedral: a stand of old-growth redwoods. Sister Veronique often comes here to pray. When she arrived here from Belgium, she told me, the redwoods prevented her from praying. She had to climb a hill near the monastery to get above them, and it was only on the hill that her heart would open to God as it had when surrounded by the wide skies of Belgium. In those early years she was depressed. Reading Hermann Hesse’s novel Siddhartha helped, but what helped most was poetry: Isaiah and Rabindranath Tagore. When Thomas Merton visited, he gave her his copy of The Tagore Reader. But her dawning realization that God was always and everywhere present came most from watching the moon. The recent full moon was hidden for three days, Sister Veronique tells me. Just because she couldn’t see it didn’t mean it wasn’t there, exerting its gravitational pull on her and on every other thing on earth. So it is with God. Always there, exerting a pull on us, but not always felt.

Before we leave the redwood grove that morning, I ask Veronique about my own prayer life. I tell her of my struggles as a father of three young boys, how difficult it is to find time for silence and prayer, how I continue to search for that center of stillness and repose that seems beyond the reach of whatever emptiness I happen to be experiencing. Sister Veronique stops, takes hold of my arm, and looks me in the eye. “You have a beautiful life, hmm?”

It comes out of nowhere, less admonishment than reminder.

I already have everything I need to begin.

One evening that week, Sister Veronique approaches me after vespers and presents me with a gift: a bottle of Belgian Westmalle Trappist Ale—a Tripel, no less. “Belgian beer is the best,” she says, winking at me. I try to convince her to join me but she won’t hear of it, so I return to Merton’s room back at the guesthouse and raise a glass in her honor. A toast to Sister Veronique, my “desert mother,” who dispenses not only wisdom but also the finest of ales.

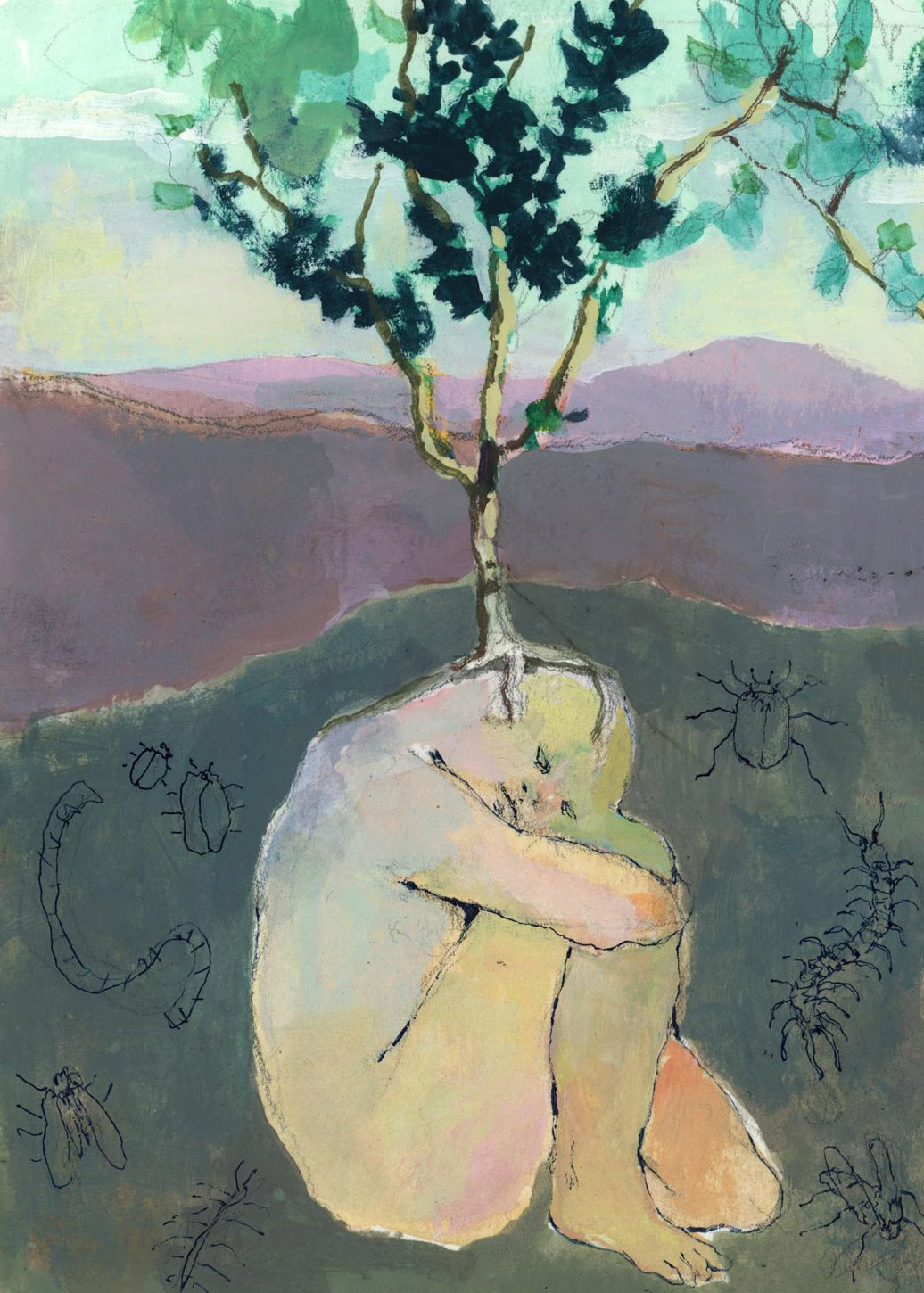

Northern California, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton

II. Shore

On the Mendocino coast, Thomas Merton sat on a grassy bench halfway between Needle Rock and Bear Harbor. Further north toward Shelter Cove he saw a manufactory of clouds where the wind piles up smoky moisture along the steep flanks of the mountains. Their tops are completely hidden.

It was probably raining back in the Mattole Valley at Redwoods Abbey, he thought. On Sunday one of the Flemish nuns danced barefoot in the choir. He was struck by the beauty of these sisters, both Flemish and American. The affection was mutual. When he told them he wanted to ask his abbot’s permission to spend Lent in the abandoned house at Needle Rock, one of the sisters told him they would all fight one another for the chance to bring him supplies.

Bear Harbor he liked better than Needle Rock. More isolated. At Bear Harbor wild irises and calla lilies grew wild among the ferns. Perhaps he could set up a trailer and live here in this hollow, surrounded by ancient Lombardy poplars, green firs, wild foxgloves.

He jotted down a line from Theophane the Recluse: Not to run from one thought to the next, but to give each one time to settle in the heart.

Eight crows wheeled in the sky overhead, casting their shadows on the bare hillside. He read the Astavakra Gita on reincarnation, looked out over the Pacific, and wrote: Reincarnation or not, I am as tired of talking and writing as if I had done it for centuries. Now it is the time to listen at length to this Asian ocean. In the fall he would cross this Asian ocean on a different pilgrimage, one that would be his last.

Before he left, he photographed Needle Rock. The great Yang-Yin of sea rock mist, diffused light and half hidden mountain … an interior landscape, yet there. In other words, what is written within me is there. “Thou art that.”

A longing for God that is vast, oceanic, yet as close to me as the waves beneath my feet.

One afternoon, one of the sisters kindly packs me a picnic dinner and I set off for Needle Rock. As she sees me off in the parking lot, Sister Kathy looks at my economy-size two-wheel-drive rental car, with its pathetic clearance, smiles, and says, “Boy, you really came prepared, didn’t you?”

The dirt road down to Needle Rock is even worse than she described: steep, heavily rutted, hairpin turns. I’m not sure I will make it back up. On the final curve down to the coast I come upon a herd of Roosevelt elk, perhaps a hundred or more grazing on a broad, grassy bench.

I pull into a small parking lot in front of Needle Rock cabin. Except for two other cars, the place appears deserted. Before I’m even out of the vehicle, a woman approaches. It’s Carla, the campground host. Carla introduces herself and immediately begins to answer questions I have not yet asked, a voluminous outpouring of trivia relayed in that way of campsite hosts everywhere who love the place they’re in. The coast is disappearing five feet a year, Carla says matter-of-factly. The cliffs are soft and they’re falling into the sea, so it’s best not to walk too close. She says this by way of warning, for my own good, because she can tell by my poor choice of vehicles that I’m in need of such advice, and perhaps I am. I nod absently through Carla’s lecture, catching about every third word, until I hear “one of the most seismically active places in the world.” I ask her to repeat.

Yes, she says, and points past Needle Rock toward a headland in the distance: the Mendocino Triple Junction. She explains how, just off the coast, three tectonic plates—the Gorda, the North American, and the Pacific—collide in a single point. A convergence of tectonic forces.

I walk north along a wide, grassy bench above the coast, a cool breeze on my face. Uphill to my right I pass the elk herd. Below to my left big rollers crash against the cliffs, coaxing the land back into the sea. Everything in bloom reaches my nose: wild mustard, bush lupine, wild iris, and the hypnotic perfume of calla lilies. I walk down a steep trail to Jones Beach and take off my shoes, the small, black pebbles warm on my toes. Around a bend I discover a flat-rock outcrop, the perfect perch on which to sit and watch the surf.

The ocean has long been the great symbol of mystical union with God. With the vast Pacific before me, I recall the story Merton told of the early Irish monks who took that metaphor literally, becoming pilgrims on the open sea.

Northern California, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton

They were called peregrini.

Inspired by Abraham, the archetypal pilgrim who left his home in Ur and traveled to the land God would show him, the Irish monks of the sixth and seventh centuries adopted the practice of peregrinatio, “going forth into strange countries.”

The peregrini set off alone or in small groups in tiny coracles made of willow and animal hide, abandoning themselves to the winds and currents of the North Atlantic. Most never returned. This exercise in ascetic homelessness was practiced by men like Saint Columba, a sixth-century monk who founded a monastery on the island of Iona, and Saint Brendan the Navigator, thought by some to have reached North American shores long before the Vikings. As Merton wrote in his essay “From Pilgrimage to Crusade,” the peregrini set out not in order to visit a sacred shrine but to seek solitude and exile. If the peregrinus had a goal, it was to find his “place of resurrection”—a specific place where he might live out his remaining days in prayer and solitude. This was not simply wandering for its own sake, Merton wrote: “It was a journey to a mysterious, unknown, but divinely appointed place, which was to be the place of the monk’s ultimate meeting with God.”

We moderns find it difficult to grasp the enormity of such an undertaking. Given how frequently we travel, we barely notice the existential threshold crossed upon leaving home. The peregrini remind us that we go on pilgrimage not to consume experience, but to be consumed. To feel again the porous borders between our inner and outer lives. If our rational age has obscured what Seamus Heaney called “a marvelous or magical view of the world,” pilgrimage helps us find it again.

Whether we think the oceangoing peregrini merely quaint or even deranged, Merton was at pains to show them as utterly sane. The historical and literary records, he wrote, show that such journeys were not simply the acting out of unsatisfied romantic notions or psychic obsessions. The peregrinatio was a result of the “profound relationship with an inner experience of continuity between the natural and the supernatural, between the sacred and the profane … a continuity in both time and in space.”

We can feel here a strong undercurrent of Merton’s own leanings. This description of the peregrinus could be read as his own spiritual dossier: “His vocation was to mystery and growth, to liberty and abandonment to God, in self-commitment to the apparent irrationality of the winds and seas, in witness to the wisdom of God the Father and Lord of the elements.… The deepest and most mysterious potentialities of the physical and bodily world, potentialities essentially sacred, demanded to be worked out on a spiritual and human level.”

The tide laps at the base of my rocky perch at Jones Beach. I should think about getting back. Here on the California coast, I’ve begun to feel the geographical cure giving way to something more durable. A longing for God that is vast, oceanic, yet as close to me as the waves beneath my feet. A feeling of presence that paradoxically comes when I feel most alone.

Was this le point vierge, the virginal point of pure nothingness that Merton found at the center of all other loves?

Perhaps this is our place of resurrection, not a fixed point but a longing, a portable question endlessly posed and endlessly answered whenever we go in search of God. A tectonic convergence of our desire for God and God’s desire for us, all of it mediated through that fickle, insatiable organ of perception that will travel to the ends of the earth to find what it craves, though it needn’t travel further than the next breath: the human heart.

On my final evening at Redwoods Abbey, I decide to give something back to the sisters. I want to honor their hospitality and pay homage to Amma Veronique’s singular gift.

Which is to say, I make a beer run.

When I roll into dinner that evening, twelve-pack of Belgian ales under each arm, Sister Kathy shakes her head in mock disapproval. It doesn’t take much sweet talk to convince her to give her abbatial permission. The party that ensues is lively by Cistercian standards, which means that the sisters drink one beer each, I drink two, and the normally silent meal gradually gives way to furtive titters, then whispered exchanges, then full-blown table conversation.

These women, most of them in the final third of their lives, have been on pilgrimage without ever leaving the monastery, yet what sights they have seen, what depths they have plumbed in their search for the life beyond life. The first pilgrimages may have been a search for the mountain where the ancient fathers were in direct communication with heaven, as Merton wrote, but here at Redwoods Abbey I’ve found the ancient mothers, and their communication with heaven occurs deep in a stand of old-growth redwoods. I am honored to have been admitted into their presence.

“We had a huud connection,” Sister Veronique tells me at our parting, “a very huud connection.” The following day I will get into my rental car and drive south to San Francisco, where I will buy a copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha at City Lights Books, catch a plane for Albuquerque, and make the two-hour drive to the Monastery of Christ in the Desert. Before I go, Sister Veronique cradles her belly with both hands and says, “Hold on to what you have and let it flower.”

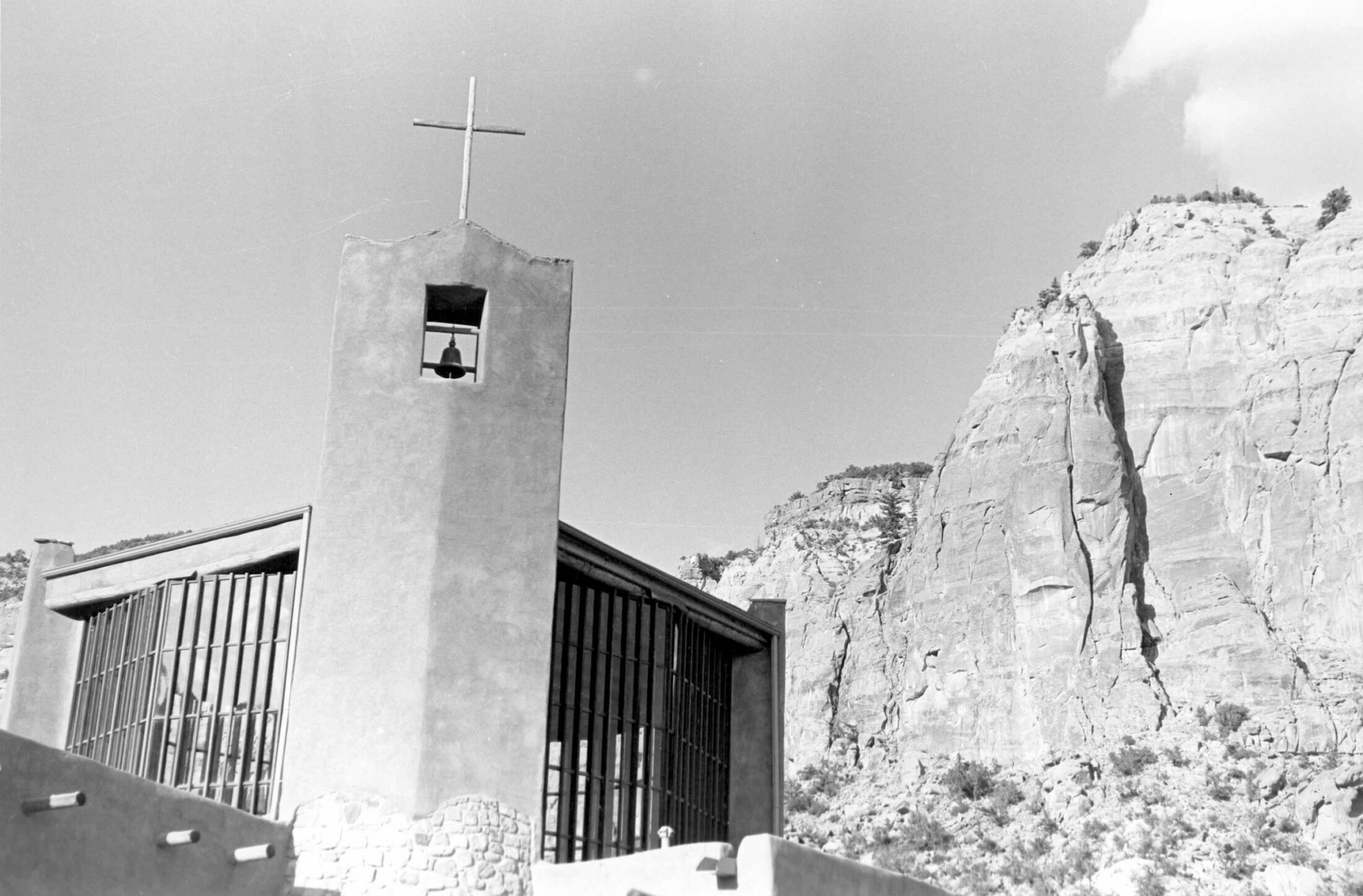

New Mexico, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton

III. Desert

Driving that May of 1968 on the road to Christ in the Desert, a new Benedictine monastery in the Chama River Canyon of northern New Mexico, Merton was bombarded by impressions. Snow up high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and then a marvelous long line of snowless, arid mountains, clean long shapes stretching for miles under pure light. Mesas, full rivers, cottonwoods, sagebrush, high red cliffs, piñon pines. Most impressed of all by the miles of emptiness.

After leaving the highway, he drove thirteen miles down a rutted dirt road and arrived at the remote monastery, a place of perfect silence. Inside the adobe church he marveled at the images of Santos as serious as painted desert birds. He spent the next several days hiking alone in the canyon. Small pine, cedar, a gang of gray jays, the cold, muddy Chama River—his eyes were hungry for all of it. He could use up rolls of film on nothing but the rocks along the canyon walls. The whole canyon replete with emptiness.

One day he lunched with Georgia O’Keeffe. He photographed Pedernal, the mesa dominating the skyline and one of O’Keeffe’s great subjects, and asked her what one sees from the top. O’Keeffe said, “You see the whole world.”

Each morning he read René Daumal’s Mount Analogue, which he declared a very fine book. “The gateway to the invisible must be visible,” wrote Daumal.

Whether Merton sought God here in this desert canyon or along the desolate Mendocino coast or in the deep hush of the redwoods, he began to suspect that his search for the perfect hermitage was a chimera. The country which is nowhere is the real home. His real home was le point vierge, the place in himself reserved only for God. Perhaps I have an obligation to preserve the stillness, the silence, the poverty, the virginal point of pure nothingness which is at the center of all other loves.

Watch the companion film, On the Road with Thomas Merton, by Jeremy Seifert

Though it has since flourished in every part of the world, Christian monasticism began in a desert.

The founder of Christian monasticism was Saint Anthony the Great. In the third century, Saint Anthony left his life in the city and went to live and pray in solitude in the wilderness of Egypt. Others soon followed his example. Within two centuries, so many men and women had fled to monasteries that chroniclers from that period report that the desert had become a city.

The Monastery of Christ in the Desert is no monastic metropolis, I discover when I arrive for a three-day retreat, but it has grown much since Merton’s visit fifty years ago. Surrounded by the deep silence of the Chama River Canyon, the monastery feels like part eco-commune, part African or Asian village. The immediately striking thing about the place is that most of the monks here are from the Global South.

Prior Benedict, the jovial right-hand man of the abbot, gives me the full tour. In front of the dormitories, he introduces me to a novice from Zambia mowing the lawn. In a side office, I meet a monk from Kenya studying ESL. In the kitchen, we bump into a Filipino monk in his eighties who was once a literature professor in Manila. He taught the metaphysical poets. Prior Benedict asks me who I think is his favorite. George Herbert? “No,” the Filipino monk says, laughing, as if the answer were obvious. “John Donne!” I learn that a number of the monks have advanced degrees. Prior Benedict has a PhD in medieval intellectual history. He is also an immigration attorney. For all the foreign brothers needing visas and green cards, Prior Benedict is their man. As we stroll through the grounds, he lists offhandedly the home countries of the brothers we pass: Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Zambia, Congo, Philippines … sixteen or seventeen nationalities in all.

The monks live off the grid. They plant vegetable gardens. Grow peonies. Build straw-bale buildings and put up solar panels to power them (theirs is the oldest and largest private solar array in New Mexico). They grow hops for their own Abbey Brewing Company. For exercise they ride horses or run trails or hike in the Chama Canyon or play volleyball—“full contact,” Prior Benedict says with a wry grin—using team names like Chastity and Stability. They study and read and play music and daily gather in the chapter room to confess their faults before one another—thereby preventing the buildup of that destroyer of intentional communities and families and marriages the world over, resentment—but mostly what they do is pray: eight services a day, more than four hours of prayer, every day of the year.

If Redwoods Abbey was a temple of stillness, the sisters embodying Rilke’s dictum that solitudes should “protect and border and greet each other,” then Christ in the Desert is by comparison a beehive. If you want solitude here, I realize, you have to hike for it.

I ask Prior Benedict for recommendations on that score. He points to several trails behind the monastery. His favorite, though, is a hike to some distant Anasazi ruins on the canyon rim across the river. Normally he would take me, but he is leaving the next day for Costa Rica. I’m happy to go on my own, I venture. But the hike is dangerous and steep—a full-day affair—and he cannot grant me his permission without a guide. “Ah well,” he says, “good reason for you to return.” We stand for a moment looking across the Chama River at the canyon rim. I picture myself climbing up to the mesa and walking in that ancient landscape, alone with God in the vast emptiness of the desert.

Christ in the Desert Monastery, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton

“You don’t choose to live in the desert,” Brother Chrysostom tells me. “You are called to live in the desert.”

Brother Chrysostom’s call came three years ago, on a three-month pilgrimage on Spain’s Camino de Santiago de Compostela. His life was already quasi-monastic—he attended daily Mass, prayed the canonical hours—yet something pulled him toward a deeper commitment. He decided to walk the Camino as a way to discern his vocation. About halfway through the pilgrimage he heard an inner voice saying, “John, I want you there.” When he got home he put his affairs in order, returned to Christ in the Desert, and took the name Chrysostom, the golden-tongued fifth-century saint.

There are many parallels between Brother Chrysostom’s life and Thomas Merton’s. Both men lived a full life before becoming monks: traveled the world, had rich social lives, were men of letters (although Brother Chrysostom is reluctant to speak of his accomplishments, I learn that he has degrees from MIT, Johns Hopkins, and Wharton, plus a doctorate in political science). When I tell him I’m following in Merton’s steps, he says, “Thomas Merton is my imaginary neighbor.” Brother Chrysostom lives in cell 8, right next door to where Merton stayed, in cell 6. He is the same age Merton was when he died: fifty-three. “Merton loved this place, and I know he wanted to be here,” he says. “Now I’m part of the continuation of his story.”

Whatever their mother tongue or place of origin, the monks here feel a certain camaraderie with Merton. To Brother Jerome, a thirty-six-year-old monk from Zambia, Merton was an ordinary monk who, by immersing himself in prayer, became extraordinary. “He shared the fruits of his contemplation with the rest of the world, and we try to do the same. We nourish ourselves individually with God, then we share it with the world.” People like Merton are guides. Jerome quotes an old Zambian proverb: “The one who has crossed the river knows the story of the river.” Merton crossed the river of prayer. He was a human being like us, Brother Jerome says, and he gives us courage to make the journey.

Over the next three days, I speak with different monks about their experience crossing that river. Brother Leander, a quiet ninety-two-year-old monk from Scotland with a cloudy right eye, takes to calling me “dear brother” and “laddie.” He sees prayer as central to the monastic life. “If we were just a jolly bunch of farmers and ecologists, well …” His voice trails off, his right hand waving the thought away. He quotes Karl Rahner, a famous midcentury Catholic theologian. The Christian of the future, Rahner said fifty years ago, will either be a mystic or cease to exist. Brother Leander looks hard at me with his good eye. “And what is mysticism? The experience of God in the interior of one’s being. I always liked Hermann Hesse’s definition of a mystic: a poet without verses, a painter without a brush, a musician without notes.” I tell Brother Leander that I pray the Jesus Prayer, a kind of mantra used by the early desert monks. “Yes, laddie, and you must pray the prayer not only with your lips or your mind but with your heart.”

Brother Isidore became a monk after fleeing war in Congo. He has seen much suffering and death, yet he possesses a deep calm and joy. “Contemplative life is the heart of the church,” he says, and that involves a commitment to silence. “Most of the time we have a lot to tell God. We must learn to be silent before God who made us.”

As I talk with these monks, each of them grows animated. They speak of God as one speaks of a dear friend, a family member, a lover. But as they make clear, such connection with God doesn’t come without struggle. The desert in the biblical tradition may be a place of stillness, contemplation, and deep encounter with God, but it is also a place of temptation, despair, and madness.

When you’ve been stripped of all but your indissoluble self, what core remains?

It was a collective madness that befell European Christianity in the medieval years when Christians gave up wandering in search of God and turned their search toward wealth and power.

By the twelfth century, the peaceful and defenseless peregrinatio of the Irish monks had been replaced by the violence of the Crusades. When knights, kings, and priests attempted to liberate the land of Abraham through force, Merton wrote, they implanted within the European psyche an insidious pattern of conquest that would repeat itself many times over the coming centuries. The promised land, paradise, the place of resurrection—such metaphors for the spiritual journey became actual places that needed to be conquered through violence and preserved through politics, and those who inhabited those places became barriers between the European pilgrim and his god. At that point, Merton wrote, Christian life took on an embattled, martial character. The colonizers of the Renaissance were capable of the horrors they inflicted on native peoples precisely because they were alienated from themselves: “History would show the fatality and doom that would attend on the external pilgrimage with no interior spiritual integration, a divisive and disintegrated wandering, without understanding and without the fulfillment of any humble inner quest. In such pilgrimage no blessing is found within, and so the outward journey is cursed with alienation.”

By the time Europeans set foot in North America, the pilgrim mentality and crusader mentality had finally fused, creating a singular and disastrous form of alienation that resulted in the conquest of indigenous peoples. As Merton wrote: “Centuries of ardent, unconscious desire for the Lost Island had established a kind of right to paradise once it was found. It never occurred to the sixteenth-century Spaniard or Englishman to doubt for a moment that the new world was entirely and rightly his. It had been promised and given to him by God. It was the end of centuries of pilgrimage.”

“There is no lost island merely for the individual,” Merton concluded in his essay on pilgrimage. “We are all pieces of the paradise isle.” In no time is that more true than now, in this age when our paradise isle is threatened at every turn. Perhaps the meaning of pilgrimage now in this age of climate change and species loss is that the fruits of our inner life in God cannot remain ours alone; they must be shared for the sake of all life. The portal to the invisible must be visible.

“What can we gain by sailing to the moon if we are not able to cross the abyss that separates us from ourselves?” Merton asked. “This is the most important of all voyages of discovery, and without it all the rest are not only useless but disastrous.” To update Merton’s question: What can we gain by fixing climate change or ending poverty or terraforming Mars if we remain alienated from ourselves? How to cross that abyss?

Brother Leander: You must let the prayer descend to your heart, laddie!

Brother Isidore: Let us be silent before God who made us.

Brother Jerome: You learn to talk to silence, and silence answers in silence.

On my last full day at the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, I decide to climb up to the canyon rim in search of the Anasazi ruins. I want to approach with as much humility as I can that holy place where silence answers in silence. Prior Benedict might disapprove of my solo mission, but by now he is in Costa Rica, and after all, I have taken no vow of obedience.

I pack light: running shoes, shorts, T-shirt, two liters of water, and some desert rations—a boiled egg, a few dates. Before I can begin climbing I first need to cross the cold, muddy Chama. The one who has crossed the river knows the story of the river. Down along the river bottom I wade through milkweed stalks looking for a way across, until I discover under a willow tree a battered, leaky rowboat. Like the peregrini of old, I launch my coracle into the swift, dark waters. The current is strong. I have to row diagonally across, working the oars with all my strength so as not to be swept downstream. Midway across the river I feel something tingle deep in my spine, that mixture of fear and wonder that accompanies any such journey: I am traveling alone; no one knows where I am going; I might not return.

The cliff face above appears impregnable save for one slot. I aim for that. The climb takes me up a steep arroyo choked with ocotillo, white sage, and juniper. On a cliff to my right I notice strange markings. Petroglyphs? I can’t be certain, for the rock face lies hidden in morning shadow. Within an hour of climbing, I near the slot and find my first cairn. Beside the cairn are signs of life: a pile of coyote scat drying in the sun, a lone cactus in bloom. This seems to be the way.

Once reaching the canyon rim I see another cairn, but a bit farther on when I top a small rise at the rim’s edge there is no trail, only a broad, juniper-choked mesa stretching away to the west. For the next hour I move outward in concentric semicircles trying to find the path. By now it’s late morning. The sun is fierce. Most of my water is gone. I find a few more scattered cairns, but they don’t lead anywhere—or rather, they lead me in circles. For another two hours I wander around increasingly uncertain of where I am. I know how to go back, but I don’t know the way forward.

In the shade of a juniper tree I sit down, confused. A breeze picks up. My sweat dries, my skin prickles. Perhaps because I feel so alone in this desert, I think of the others on my journey who’ve confronted this same emptiness. Bashō. The peregrini. Sister Veronique, Sister Kathy. Brother Isidore, Brother Chrysostom, Brother Jerome. And Merton. I’ve had many trustworthy guides on this descent to the heart, but here in the desert I have no guide, and perhaps for now I no longer need one. Sister Veronique said I should hold on to what I have and let it flower. What I have, rooted in me since childhood, are these unresolved feelings of exile, loneliness, neglect. What if I make those my offering? When you’ve been stripped of all but your indissoluble self, what core remains?

This is the work: to take these feelings of loneliness and exile and bring them into the furnace of the heart, where emotional abandonment becomes mystical abandonment.

Sitting in this tiny patch of shade, surrounded by white sage and ocotillo, I bring these thoughts into prayer. Normally my prayers are a dull litany of requests and complaints, the hypes and gripes of a lukewarm spiritual life, but here on the edge of this vast mesa, I feel those petitions giving way to something more compelling, an opening into a more spacious country. An uncomplicated resting in God, who seems to have no other agenda than to welcome me into this place of silence and mercy and at-oneness. A feeling of Presence that is so much more than the breeze on my face or the sweat evaporating on my skin.

I never find the Anasazi ruins. Just as well that I don’t. After a time, I swallow the last of my water, stretch my stiff legs, and retrace my steps back to the last cairn along the canyon rim. I can see far below on the river’s edge a small, damaged vessel, waiting to ferry me home.

New Mexico, May 1968.

Photo by Thomas Merton

Coda

Let us see him once more. He’s driving south along the Eel River under trees as old as the faith he follows. Soon he will be back home in Kentucky, watching the small hardwoods fill with new growth and wondering if they are even real trees, so much are his thoughts filled with redwoods. Who can see such trees and bear to be away from them? I must go back. It is not right that I should die under lesser trees. Six months from now, in Bangkok, after speaking to an international gathering of monastics, he will return to his room for a bath, reach for a fan, and receive the accidental electric shock that will end his life. His body will be placed on a transport plane carrying the bodies of American soldiers killed that week in Vietnam and then returned to Gethsemani, with its lesser trees, where it will be waked, prayed over with Psalms, wrapped in a monastic habit, and planted in the earth beneath cedars and oaks and sycamores that I will walk under fifty years later. But now, driving south along the Eel River, he is still innocent of what’s to come. His journey has only begun. As we see him there in the passenger seat, spinning down Highway 101, we need not tax ourselves with forethought of grief, for here in this ongoing moment, there is only the worshipful cold spring light on the sandbanks of Eel River, the immense silent redwoods. The light leads him onward to his place of resurrection, he knows not where.

- Photographs by Thomas Merton used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.

Permission to quote from Thomas Merton’s published works, including the journals Mystics and Zen Masters, Loving and Living, Thoughts in Solitude, and No Man Is an Island, granted by the Trustees of the Thomas Merton Legacy Trust.

On the Road with Thomas Merton

In May 1968, Christian mystic Thomas Merton undertook a pilgrimage to the American West. Fifty years later, filmmaker Jeremy Seifert set out to follow Merton’s path, retracing the monk’s journey across the landscape. Amid stunning backdrops of ocean, redwood, and canyon, the film features the faces and voices of people Merton encountered.