Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee is a Sufi teacher who has specialized in dreamwork and Jungian psychology. He is the author of numerous books on Sufism and spiritual responsibility in our present time of transition, including For Love of the Real and Seasons of the Sacred, and editor of the anthology Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth. His most recent book is Seeding the Future: A Deep Ecology of Consciousness.

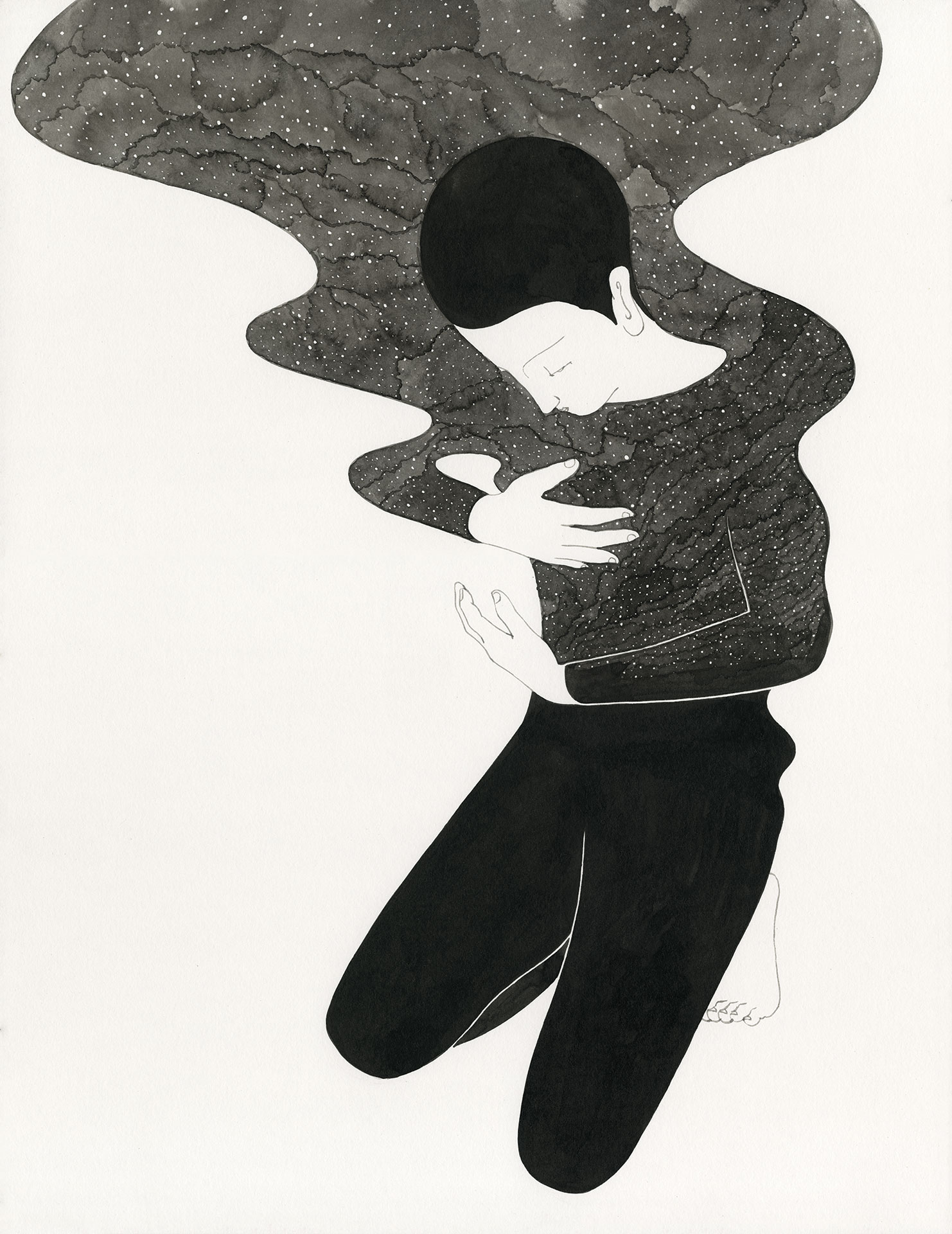

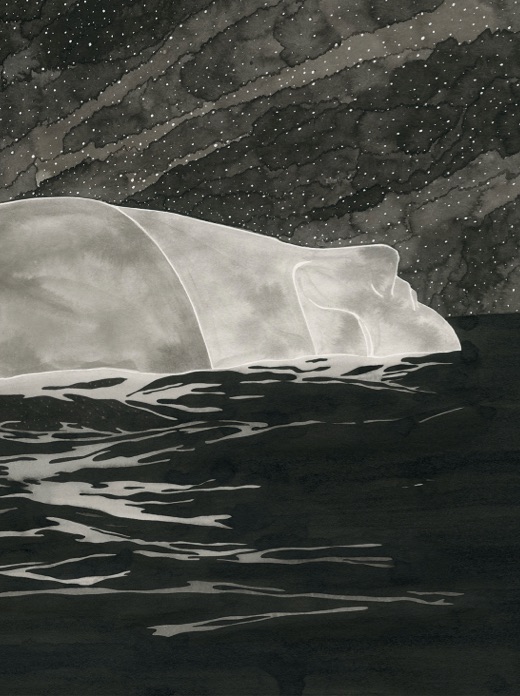

moonassi is an artist from Seoul, Korea, whose black-and-white drawings explore emotion, inner dialogue, and the human psyche. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Migrant Journal, and elsewhere, and has been exhibited in Seoul, New York, and London.

Witnessing how humanity is tearing apart the web of life, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee reminds us of the deep ecology of consciousness we once held—a threshold open to the place where the land sings—and calls us to return our awareness to a fully animate world.

I like to walk early and am often alone on the beach, the ocean and the birds my only companions, the tiny sanderlings running back and forth chasing the waves. Some days the sun rising over the headlands makes a pathway of golden light to the shore. Today the fog was dense and I could just see two figures walking in the distance until they vanished into the mist, leaving a pair of footprints in the sand until the incoming tide washed them away. It made me wonder what will remain in a hundred years, when my grandchildren’s grandchildren are alive? Will the rising sea have covered the dunes? Climate crisis will by then be a constant partner, and so many of today’s dramas will be lost in a vaster landscape of primal change.

Sensing this reshaping of the seashore, where the waves roll in from across the Pacific, makes my mind stretch across horizons. How this land and our own lives have evolved. One story of science says it was only seventy thousand years ago that humans left Africa on their long migrations across continents, arriving here on the Pacific coast just thirteen thousand years ago, when the Bering Strait was dry land and not ocean; or possibly they came earlier in boats down the coast.1 But how was life then, long before the written word, when we traveled as small groups, communities of hunters and gatherers? What was the consciousness of our ancestors, before agriculture, long before cities or our industrial way of life? And what did we lose as we settled the land, and then forgot it was sacred?

They may have carried few possessions, but their consciousness contained a close relationship to the land, to its plants and animals, to the patterns of the weather and the seasons, which they needed for their survival. Fully awake with all of their senses, they had a knowing, passed down through generations of living close to the ground, even as they migrated across the continent. Today we are mostly far from the land and its diverse inhabitants. Cut off from these roots, we have become more stranded than we realize, and while our oncoming climate crisis may present us with many problems, we hardly know how to reconnect, to return our consciousness to the living Earth. It is as if, having traveled to the far corners of our planet, we now find ourselves in an increasing wasteland without knowing how to return to where the rivers flow, to where the plants grow wild. And unlike our ancestors, we cannot just pack up and move on, because this wasteland surrounds us wherever we look, like the increasing mounds of plastic and other toxic material we leave in our wake.

And sadly, tragically, our consciousness has become divorced not just from the land under our feet but also from the unseen worlds that surround us. Anyone who looks at the animals in the Paleolithic cave paintings in southern France with a receptive awareness can see that the physical and spirit world are infused together. Those early artists were imaging not just physical animals, but spirit beings, shamanic, magical. This is part of their mystery and intensity. And this knowing continued for thousands of years, whether experienced in relation with the powerful beings that for the Native Americans are present in all natural things, invisible but everywhere; or expressed through veneration of the kami, the sacred spirits that exist in nature, mountains, rivers, earthquakes, thunder, animals, and people, which until recently belonged to an elemental Japanese consciousness.2 For most of our history the inner and outer worlds were woven together, as shown in the myths and stories that defined our existence.

Have we wandered so far from the source that we cannot return?

Walking the shoreline, watching the little birds searching for insects, my awareness drawn to the sky, the sea, and the shifting sands, I wonder at this gulf between the simple, magical awareness of our ancestors and our present-day mind, as cluttered as our consumer world. What has happened to our consciousness, now divorced from the multidimensional existence that used to sustain us? Did we need to exile ourselves from this primal place of belonging? And now, as we tear apart the web of life with our machines and images of progress, is there a calling to return, to open the door that has been closed by our rational selves?

When the fog is dense and you can only see a few yards in front of your feet, the world around becomes more elemental. Watching each wave come to the shore is like watching the breath. Sometimes my feet become wet from the rising water, or I move farther up the beach. I try to keep my mind empty, part of the sky and the waves, simple, essential. Here nothing is separate, and the inner and outer worlds are closer.

I cannot return completely to a world in which spirit and matter are always united—I carry too many images from a culture that has denied that the inner world even exists. But I can live closer to this threshold, this place where the waves and the sand meet. I can recognize how easily our defined world can be washed away—how soon the waters will rise. And when many of our toys of triviality, the “things” that clutter our houses and awareness, are lost in the tsunami of climate change, I can be like the Moken, the nomadic boat people of East Asia, who knew to go to deeper water when the waters rose. They remembered the old stories, the old ways, the wisdom of their ancestors, and so their boats rode out the storm—unlike the fishermen who remained close to the shore and perished in the tsunami.

Always there is this primary place of belonging in the land and in our souls. It used to be a part of the way we lived, how we walked and breathed. Crossing oceans and continents, we carried it with us, a lodestone for our existence. For thousands and thousands of years, it was an essential part of us, never forgotten, because how could you forget the feel of the rain on your skin, or the sound of water flowing over stones? How could you forget the stories and songs passed down through the generations? It is only very recently in our human history—only a few hundred years amidst thousands—that we forgot, that we lost this thread, that our mind ceased to be a part of both the land and the unseen worlds, that we forgot that everything we can see and touch is sacred and in our forgetting no longer inhabited a world in which everything is alive with spirit, the wind and the rain, the plants and animals.

Have we wandered so far from the source that we cannot return? Will climate crisis isolate us even more in our cities as nature becomes more unpredictable? As we try to use our science, our computers, to save us? Or is the doorway to return nearer than we know, just as in that moment when we awake and our dreams are still present, before they are lost with the daylight? What would it mean to return to this numinous land, alive in ways we no longer understand, where the Earth can speak to us in its many voices? Or more vital, can we transition through this present self-created crisis without this inner and outer knowing, without this awareness that was central to so much of our human journey?

It is easy to dismiss the magical world as just a fairy tale belonging to childhood or old tales, to maintain that what we need at this moment more than ever is hard science, that carbon reduction and loss of biodiversity are our most pressing concerns. And yes, there is important work to be done reducing our industrial imprint, restoring wetlands and wild places. But if we do not remove the rational blinkers from our consciousness, how can we respond to the deeper need of the moment and recognize that we are part of a fully animate world? If we are to become partners with the Earth, living our shared journey, we have to once again speak the same language, listen with our senses attuned not just to the physical world but also to its inner dimension. We cannot afford to continue to dismiss so much of our heritage—the thousands of years we were awake to an environment both seen and unseen.

And yet this knowing has been censored so effectively from our present mind that we do not even know how to read the signs, how to look and listen, how to be in the space where dreams are woven into consciousness. We may speak about the need for a new story, one that is not based upon exploitation and greed but recognizes the interdependent oneness of the living world. But real stories arise from the inner worlds, only then do they carry the numinous power that can change a civilization. Myths are not rational but belong to a deeper dimension of our psyche. We can see the emotive power of the false stories that surround us—whether the recent myth of endless economic growth that is the foundation of our consumer world, or the more recent distortions of social media that grip our collective consciousness. We are living these pathological stories without fully recognizing how much we respond to their emotive and psychic power. The cold facts about climate change and loss of species have not changed our behavior, while conspiracy theories and stories of stolen elections have seized our beliefs. Is our collective consciousness only open to dark myths, such as the Kraken, a tentacled creature of Norse mythology that arises from the deep, swallowing ships?3

Now as we stand at this crossroads, do we have to wait for our present society to fall apart? Are we caught in too many patterns of social and economic divisiveness? Where do we find the hidden gateway into the garden—a place where we are no longer exiles in our own land, living by the “sweat of our brow,” but can hear and then live the songlines of the land; where dreaming nourishes our daily life? Our ancestors are still all around us, in our DNA, in the land, in the spirits still present behind the veils of our rational self. In the millennia of our human history, it is only a few years since most of us divorced ourselves from these companions and decided to walk alone, unaccompanied, no longer understanding our primal relationship to the Earth and Her ways, no longer speaking the same language, singing Her songs. And those few who carried that remembrance experienced the suffering and pain of that separation, as they struggled to stay true to the songs, dreams, and ceremonies in a world increasingly covered with enforced forgetfulness.

Is it enough just to acknowledge that our ancestors lived in an animate world that is still around us, even if invisible to our eyes, intangible to our other senses? They lived in a world of kinship on many levels: not masters, not the dominant species, but part of a living tapestry—just one species among many—where the hunter asked the spirit of the animal for permission to hunt, and the gatherer for the plant’s blessing to harvest. Here there was no hierarchy but an interdependent world both physical and spirit, all part of one community that could communicate through dance and dream, song and prayer.

If we are to become partners with the Earth, living our shared journey, we have to once again speak the same language, listen with our senses attuned not just to the physical world but also to its inner dimension.

For them dreaming and waking were not separate but part of a multilayered texture of existence, where dreams could guide the hunt and the spirits of animals and plants were welcomed. And sometimes they ventured deeper into the spirit world through visions and had access to a wisdom that could help their whole community. For example, the Lakota medicine man, Black Elk, who walked this land less than a century ago, had a seminal vision when he was nine years old that took him to where the horses were singing, and the Thunder Beings spoke to him of the destiny of his people, how his “nation’s hoop was broken.” The spirits called upon him to help restore his people through an awareness of all of life’s sacred nature and its inherent unity:

And while I stood there I saw more than I can tell and I understood more than I saw; for I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit, and the shape of all shapes as they must all live together like one being.4

Our present world is divisive, our consciousness fractured. Our collective values produce greed and endless desires. Science and its foster child, materialism, have become a broken mythology, evident in the ecocide it has created. Where are the visions to guide us, the spirits to sustain us, the singing horses to accompany us? Are we still hoping to find an answer in technology, in its soulless succession of ones and zeros? Or can we begin to remember the lands we have left, the spirit-filled world we have abandoned?

My own garden, on a hillside beside the bay, is a place where the worlds come together: colors and fragrances; lavender; buddleia bushes, whose honey-scented flowers are so often full of bees; chamomile, yellow and white; jasmine, a cascade of evening sweetness; and the soft magic of the spirits that are welcomed, at home like the quail with her babies in the early summer, hiding between the plants. This is how the land was always alive, seen and unseen, movement and stillness. And we were a part of it all, our senses attuned in ways long lost. And now, as the Earth is calling out to us to remember Her sacred ways, there is the possibility to return, to walk as our ancestors walked, to be a part of the world coming alive after a long winter, after storms and snow, after a landscape so barren it pains the eyes.

Here, where the land sings, where the worlds meet, is a way to be that resonates with both the soil and the soul. Making a garden sing, for the unseen to be present, is a simple act of welcoming the worlds our ancestors knew, the spirits of the land as well as the beings of light. I have found it is simplest through an openness of heart and a deep knowing that we are surrounded, nourished, and met in ways beyond our rational minds: a multidimensional kinship. The colors of the flowers then reveal a vibrancy beyond the physical, and even the stones in the garden feel awake.5

This is a simple celebration of the wonder that was always around us, and a nourishment we need for our shared journey together into an uncertain future. It is hard to see how the coming decades will unfold. If the year of the pandemic has taught us anything it is how unpredictable the present moment is, how fragile our present systems. We do not know how much of our present way of life will be lost as the wildfires rage and the seas rise. Will we retreat into the bunkers of materialism, or step into a different way to live with the land? But this moment is also an opportunity to return to an essential awareness that belonged to our ancestors, which, although we have dismissed and forgotten it, is not so far away.

On any journey it is necessary to decide what to take—both for traveling and for the new life that awaits. This deep ecology of consciousness that embraces a fully animate world can sustain us, giving us access to the wisdom of the Earth, a knowing we need for the turbulence of this transition. Without this quality of consciousness there is the danger that we will just remain in the barren wasteland created by our rational mind, that we will not fully wake up from the nightmare that is poisoning the planet. Maybe the land and its spirits can welcome us awake, help us to fully see, hear, and inwardly sense the garden we never really left.

- While the creation stories of North America’s Indigenous peoples teach that they have always been here, that they were created here, science-based theories tell different stories of how the First Peoples arrived to North America. For more than half a century, the prevailing theory was that thirteen thousand years ago the Clovis culture arrived: small bands of Stone Age hunters who walked across a land bridge between eastern Siberia and western Alaska, eventually making their way down an ice-free inland corridor into the heart of North America. A subsequent theory is that fifteen thousand years ago the earliest inhabitants arrived by boat, traveling down the Pacific shoreline. While a recently emerging theory is that humans may have arrived earlier, at least twenty thousand years ago, when the Bering Strait was high and dry.

- Kami are the spirits, phenomena, or “holy powers” that belong to nature and are manifestations of musubi, the interconnecting energy of the universe. They are revered in Shinto, the earliest religion of Japan. There are, of course, many other inhabitants of the unseen worlds—from angelic beings to darker, elemental forces. For example, the Celtic tradition refers to the three realms: Annwn, the world below; Abred, the middle world of nature and human affairs; and Gwynfed, “the white life,” the upper world or heavens. Nature spirits or devas—which inhabited much of our pre-industrial world—belong to the middle world, while angels, beings of light, belong to the upper world.

- Conspiracy theorists supporting Trump have spoken about “unleashing the Kraken.”

- This is part of a much longer and very powerful vision in which the Thunder Beings—spirits revered like human grandfathers—spoke to him. His vision continues: “And I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.” The whole vision is recorded by John G. Neihardt in Black Elk Speaks.

- Sacred landscapes have this quality: for example, the mountains that are the “heart of the world” of the Kogis in Colombia, or mountains and lakes in Tibet imbued with sacred meaning, where protector deities are often painted on the rocks. Some of the land around Glastonbury in England has a similar, ancient earth magic.