Hala Alyan is the author of the novels The Arsonists’ City and Salt Houses—winner of the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the Arab American Book Award and a finalist for the Chautauqua Prize. She has published four collections of poetry, most recently The Twenty-Ninth Year. Her work has been published by The New Yorker, the Academy of American Poets, Lit Hub, The New York Times Book Review, and Guernica. She lives in Brooklyn, where she works as a clinical psychologist.

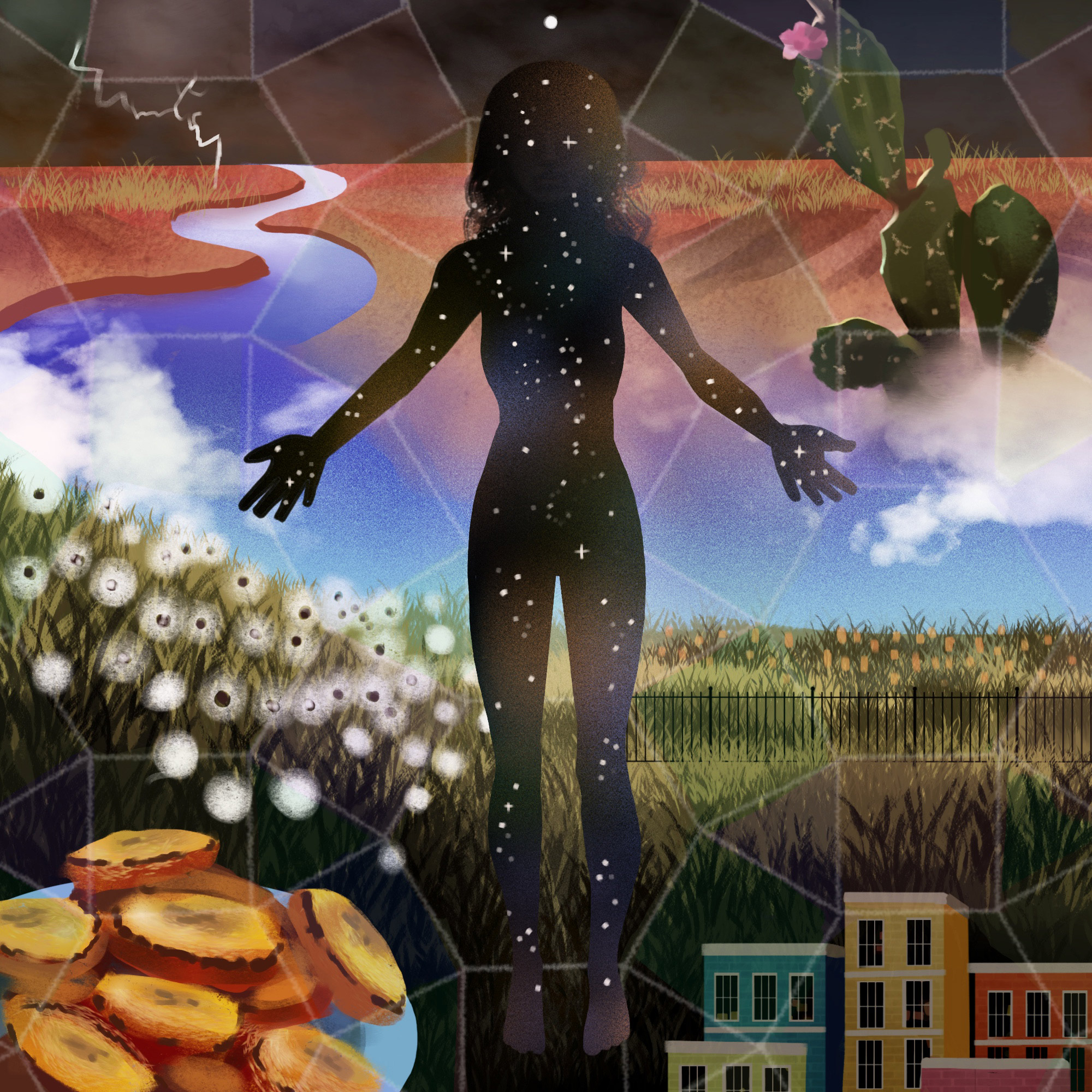

Leonardo Santamaria is a first-generation Filipino-American freelance illustrator. He is the recipient of a Gold Medal from the Society of Illustrators (New York) and a Silver Medal from Spectrum Fantastic Art. He has contributed to motion projects for Buck animation studio. His clients include National Geographic, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The Guardian, and more. He currently lives and works in South Pasadena, California.

Hala Alyan reluctantly steps into the realm of fear, exploring its manifestations, the hold it can have over us, and practices of surrender.

If you slip or have a minor spill … [t]ake note of the circumstances of your fall, but don’t allow your body to brood on the memory.

—René Daumal, Mount Analogue

I regret pitching this essay.

It feels important to start here: I don’t want to write about fear. When I first came up with this topic, it felt important and appealing, something that might be edifying in the process of writing it. But then something odd happened: I started to procrastinate. Yes, that’s part of the writing process, but this was different. The summer came and peaked without me writing a single word. Every time I sat down to work, I’d get a headache or remember a household task. The year had taken a lot out of me—most of us—and it was nowhere near over. I was exhausted from fretting. I was bored with talking about fear. I didn’t want to think about it anymore. By August, with the deadline rapidly approaching, I had started organizing my notes.

Then the month collapsed on itself. First the port explosion in Beirut, where I’d lived for many years, which awoke in me—even from my distant, lucky perch in the United States—a roar of dread and nightmares. Three weeks later, I got a positive pregnancy test, promptly followed by concerning blood work, which left me scared—eight hours away from home, on a secluded island in Maine—and unsure whether I was miscarrying or having another ectopic. (It was, mercifully, the former.) By the time I got home to Brooklyn, I was certain that my nervous system was wrecked from all the fear. A week later, the strain on my marriage nearly ended it.

This trifecta bought me an extension on the deadline. The fear of violence, fear of illness, fear of abandonment, brought me eye to eye with the subject of this essay. The earlier procrastination suddenly seemed clear as day: I wasn’t bored with the subject matter; I was afraid of it.

It was a relief to get the extension. Of course I couldn’t work on this now, I thought. My thinking started to snowball. Why was I even writing this? What made me an authority?

“Who wants to read an essay about fear written by somebody perpetually stalked by it?” I fretted to a friend. She hesitated.

“Doesn’t that make you the perfect person for the job?”

The word exploded like a light bulb. I was waiting for perfection. I was waiting to vanquish the thing before writing about it. I was holding out for the version of me that had conquered fear to sit down and do it.

Last year in Paris, I got caught in the heat wave of July. Night after night, I’d sleeplessly roll around the sweaty sheets on the bed of my sublet, drifting in and out of unpleasant dreams about thunderstorms and feral cats. I got so sick with food poisoning, I could barely lift my head. My mother likes to tell the story of me as a toddler, how I ate cat shit in our backyard in Cyprus and got so ill that I needed to be hospitalized. I’ve had a weak stomach and paranoia about dehydration ever since. It frightens me to see my veins bulge and turn bluer.

My mother visited me in Paris. We went to a tiny restaurant, where we ordered salad and sandwiches, and I kept tapping the plate nervously with my fork.

“It’s funny,” my mother said. “You get a certain look in your eyes when you’re scared. It’s the same one you had when you were a child. I see it now.” Only she didn’t say “scared.” She said اكلتيها رعبة—a peculiar phrase in Arabic that translates literally to “You’ve eaten some terror.”

The comment made me spiral. For some reason, the very concept of my terror was terrifying, like looking into a mirror to see yourself altered. New eyes, new mouth.

That’s the thing about fear. It’s an emotion that rarely exists in the present moment. Often it needs the past or future to feed on, a feedback loop to keep it alive. As psychiatrist Mark Epstein notes in his book Open to Desire, “We are the only animal that in the face of trauma continues to retraumatize itself, playing and replaying that which has already happened to frighten us.” This is the trick of fear: it often breeds itself.

As an experiencer, I loathe fear. But as a writer, as a therapist, as an observer, it fascinates me—more than any other emotion. It is essential for our survival, an emotion that propels us, moves us. But it can also immobilize us. In high doses, it can be deeply incorrect, sending false alarms throughout our psychological ecosystems: well intentioned, misguided.

That’s the thing about fear. It’s an emotion that rarely exists in the present moment. Often it needs the past or future to feed on, a feedback loop to keep it alive.

One Saturday evening, I’m discussing the essay with my husband Johnny when he suddenly interrupts me.

“You’re very brave,” he says. “I forget to tell you that. You’re always doing scary things.”

Up until recently, I would’ve dismissed this. But my understanding of courage is different now. I see how relentlessly it is linked to fear. We don’t acknowledge this enough in our culture. I was a fearful child—bred in the reverberation of wars and displacement, in the folds of a fearful mother and aunt—but I was also a brave child. I walked up the stairs into my elementary school every morning, dove sloppily off the board at the YMCA pool, extended a trembling hand toward the neighbor’s dog, all while being afraid. When I hit adolescence and my early twenties, that fear became masked in alcoholism and impulsive behaviors. But when I got sober, there it was again: my fear, my old buddy, awaiting me like a driver in an airport terminal, my name scrawled on a piece of cardboard.

After embracing sobriety, I found myself with worsening anxiety and a budding perfectionism (and eating disorder). Essentially a Molotov cocktail for fear, which thrived on my not knowing and my low tolerance for uncertainty. Over the years, I’ve had periods of unexplained panic, often lasting for a couple of months, accompanied by obsessiveness and dread. The fear in those times was less concrete and more whispery, existential: fear of nostalgia, fear of certain times of day, fear of remembering dreams.

I’ve been lucky in many ways. I’ve always remained functional. I’ve had enough language to explain it. But the legacy of those experiences is unmistakable: I’m afraid of fear, its very whiff.

Fear plays a particular role in suffering. As a therapist, I often see fear as a discrete phenomenon or sensation, one that’s attached to an object—the scary thing. A clown, perhaps. Or a tornado. Like most human emotions, it has a function. As a phenomenon, it heightens our perception and alertness, shepherding our fight-or-flight responses, which can be crucial in keeping us alive. It’s the jolt that makes you leap back at the sound of a car honk. I’ve found it useful to think of it as a well-meaning hijacker, one that lives and dies by a single code: keep her safe at all costs. It’s hard not to feel some gratitude toward fear when it’s conceptualized this way. But when you’re up at three in the morning, your heart racing, wincing at the sound of the air conditioner, that goodwill can quickly sour. The same mechanism that shields can go haywire, as brain imaging of trauma and other stress-related disorders shows: the medial prefrontal cortex functioning slows down and the amygdala lights up like Roman candles, interrupting the brain regions that control emotional regulation and higher-order thinking. With fear in the front seat, calm, rational reflection is quickly tossed to the curb.

Certain mental health conditions and prolonged exposure to stress can disrupt the fear circuitry in the brain, where the memory of trauma becomes imprinted in the limbic system and replayed in moments of objective safety. The metaphor often used is a faulty smoke detector: traditionally, smoke detectors are indicators of fire, but a hypersensitive one goes off when you’re cooking—namely, when there is no real threat.

Fear as a phenomenon is rampant in modern life. Why? Partly this is the legacy of industrial and technological advances, which have given us everything from plastics to pesticides, nuclear power to mobile phones, biotechnology to global travel, and more. The benefits of these advances are clear: lower childhood mortality, fewer wars, more accessibility than ever before to clean drinking water, vaccinations, etc. (Though it is worth noting that this is often within the so-called Global North; many places that are plagued with the legacy of colonization—or are currently under occupation—continue to struggle.) But these advances have their costs. They have left climate and ecological crises in their wake. Modern medicine has bolstered life expectancy, yes, but it’s also helped fuel a population explosion. But perhaps the most profound changes have come through communication technology. Most people I know—myself included—are rarely without their cell phones: little metal umbilical cords that feed us astounding amounts of information and breed an appetite for immediacy.

Risk perception contributes to the overall extent of our fear and is affected by factors like trust (the less we trust those supposed to protect us, from parents to corporations, the more afraid we will be) and control (for example, people tend to feel safer in cars than in airplanes because of the illusion of agency). Similarly, a risk we choose—such as cigarettes—seems less dangerous than one imposed on us, especially one that feels new—like COVID-19. Risk perception research reveals the same thing: it’s rarely logical and it’s driven by dread. Awareness of a risk makes it seem more likely to happen. If the press is covering a recent kidnapping, we feel more certain that it’s likely, even though the actual likelihood hasn’t changed. We dread things like cancer, while far fewer of us fear heart disease, despite the fact that it is statistically more likely to kill you.

In short? We often fear the wrong things because they feel right.

It feels irresponsible to discuss fear without considering misinformation. It’s true that this isn’t solely emblematic of our times: reading articles from the time of the “Spanish flu,” when people protested mandatory mask wearing, one gets an eerie sense of déjà vu from the photographs of defiant, naked faces and snipped-off masks. One can argue that a white supremacist might be motivated by a fear bred from misinformation, but so were some Nazis. Misinformation isn’t the cause of fear so much as its accelerant, a gasoline methodically drizzled by those in power since the beginning of recorded history, from Octavian’s smear campaign of Mark Antony in ancient Rome to the “weapons of mass destruction” rhetoric behind the Iraq invasion.

What is different about our era is that technology spreads fear like wildfire. What took years to carefully seed in decades past can now be planted in an afternoon of tweeting. The “Pizzagate” conspiracy was first tweeted about on October 30, 2016, a mere month before a man arrived at the restaurant with an AR-15 rifle and opened fire on the walls. Fear is effective, and its effectiveness is what makes it dangerous. Often there is a classic create-a-problem-to-offer-the-solution tactic: creating an anxiety by sowing fear, then offering the solution to the panic—anything from a diet pill to an identifiable enemy.

The true resistance here, then, is our attention. As technology ethicist James Williams writes in Philosophers Take On the World: “In the short term, distractions can keep us from doing the things we want to do. In the longer term, however, they can accumulate and keep us from living the lives we want to live, or, even worse, undermine our capacities for reflection and self-regulation.”

The research is clear: we are unreliable narrators of our lives, and fear is an unreliable narrator of risk. Something that seems scary is likely to scare us. I always think about my years in Lebanon. I lived in the country for nearly a decade, including my undergraduate years, which saw the assassination of the prime minister, countless upheavals and protests, and the 2006 war. The amount of risk-taking behaviors that my friends and I participated in during those years is now astounding to me, from mouthing off to soldiers to sneaking into Hezbollah tents. And yet, there is one very prominent memory that stands out. During the war, my mother and aunt wanted to evacuate. The airport was bombed; one of the remaining routes was by sea. I dreamt that the ship exploded and we all died.

Faced with an uncertain future if we stayed in the country mid-war, I was more afraid of the ship exploding because it felt true.

(Fear, like obsession, never apologizes. When the ship docked safely in Cyprus, the worry was promptly tossed out of my mind without a second thought. If I tried to interrogate its faultiness, it airily flapped its hand and countered, Well, this time it didn’t come true, but who knows about next time. Such logic is impossible to argue with.)

Fear can be a particularly challenging emotion because it is so deeply felt in the body. We crowd in when we’re afraid, instinctively protecting our organs. Our throats dry. Our hands tremble. Perhaps because of the brain-gut connection—that intimate link between the brain and the gastrointestinal system, wherein signals travel a two-way street. More recently, research has shown that the reason deep breathing helps ease fear is that it activates the vagus nerve—a key part of the parasympathetic nervous system—which is responsible for reducing stress responses, heart rate, and blood pressure. In certain Hindu and Buddhist traditions, fear is said to be a symptom of a blocked third chakra: the solar plexus chakra.

Although the systemic changes of fear ultimately protect us in the short term, the longer stress responses last, the worse the effect. Stress and ongoing fear responses are associated with a weakened immune system; increased cardiovascular damage; gastrointestinal problems, such as worsening ulcers and irritable bowel syndrome; compromised formation of long-term memories; and damage to certain parts of the brain, such as the hippocampus. This is known as living under an allostatic load, when our systems start to strain under the unrelenting stream of new triggers: the stream of news and media availability, the strain of urgency, constantly sounding alarms. Many of us aren’t just overwhelmed—we’re chronically afraid.

The hunt for a fear “cure” can be more damaging than the fear itself. It can create a precedent in the mind that the only safe state is one without fear, and that can become prime territory for conditions like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, where the hunt for relief becomes problematic, and in fact is the primary upholder of the fear. What was once a solution becomes the problem.

Different cultures intersect with fear differently. Capitalism feeds and stokes fear in our culture; values of production and accumulation lend themselves to perfectionism and control, and that trickles down. Our society is bent on erasing anxiety, sanitizing death, feeling “good.” At their core, these endeavors reflect a desire to establish control, when we would do well to accept that, frankly, we are not in control. And the more afraid we are, the more we rely on security in whatever form we can get it. Higher rates of fear have been shown to correspond with increased conservative voting and also authoritarianism of the mind. We become addicted to control. Uncertainty becomes more and more unacceptable.

We are unreliable narrators of our lives, and fear is an unreliable narrator of risk.

I grew up in a superstitious household, as many Arabs do. We turn over upside-down shoes. We touch bread to our lips and foreheads before throwing it away. When something good happens to someone, my mother—and, yes, now I—will circle the air around that person with pinched fingertips while making kissing sounds. Many people I grew up with believe that dreams foretell your future, that we all possess intuition; some of us are just listening harder. These traditions can feel beautiful to me, a way of being connected to our ancestors, who also read coffee grinds and shared their perplexing dreams; but at times I’ve struggled with superstition as a gateway drug to fear. That’s why I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with astrology; I had to delete the app Co–Star because I noticed that the prediction of a bad day became a guarantee of one.

And yet I hunger for it as well. I go to tarot readings. My impulse—my knee-jerk, first response—is to believe. One autumn afternoon last year, I went to my friend’s Reiki healer. The woman kept guessing things wrong. She’d touch my throat and say I should try storytelling.

“I’m afraid of a baby, but I want one,” I finally suggested helpfully.

“Ah, yes,” she said. Her hands shifted to my hip bone. “Yes, yes, I feel it now.” After the session, I nodded when she asked if I felt different. Maybe I do, I thought to myself as I left.

Fear overwhelms us when a once-appropriate signal misfires and becomes an eternal reliving of trauma, like a gear shift stuck in overdrive. This may exist beyond a particular life span too. Studies in which rats were given electric shocks while smelling orange blossoms have shown that their offspring flinch at the same scent, even when they’ve never encountered it before. The fear has been epigenetically passed down.

My meditation teacher once told me about a passage in psychotherapist Adam Phillips’s book On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life: when a claustrophobic client says he might die if he goes into a crowded space, Phillips mentally retorts, “Why not agree to die and see what happens?”

I think about this often. Why not agree to die and see what happens? It speaks to the combination of courage and surrender that is essential when working with fear. Concepts like surrender and acceptance have become catchy buzzwords in what I think of as the Insta-fication of wellness, in which inspirational posts and memes are recycled with colorful, upbeat wallpapers. It’s the commodification of wellness and often not a true model of it.

My fear worsened after Paris. I decided to try Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) therapy. It’s a common mode of treatment for panic disorders, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and I’d long been curious about it. Besides, I’d started to notice a curious phenomenon: the more I tried to unpack my fear, the worse it got. I wanted to try something different.

The exposure therapist’s office was a block from mine. She patiently listened to me ramble about my nerves being frayed and finding myself stuck on the same fears over and over. “Your mind has gone rogue,” she said at the end of our first session.

“And we’re going to rein it in?” I asked hopefully.

She smiled. “We’re going to fear the chaos less.”

Exposure-based therapies are founded on the tenet of habituation or learning, depending on whom you ask. (For many clinicians and researchers, it’s both.) From a conditioning perspective, you identify the thoughts, emotions, and body-based responses associated with a particular (feared) stimulus and then break the patterns that maintain the fear: avoidance, reassurance seeking, rumination, compulsions. This forces you face-to-face with the feared object, and eventually, the theory goes, you habituate. (This is a fancy way of saying that you get used to it.) From a learning-based perspective, the exposure to a feared stimulus eventually leads to less distress because you are learning that you can handle the distress; you are also learning what actually happens when you face the stimulus (versus creating catastrophic narratives around it). The only way to effectively expose yourself to the fear, however, is to simultaneously response prevent, which means eliminating safety behaviors and compulsions. They only serve to neutralize one’s distress and anxiety, which ironically just strengthens it in the long term.

When I talk with Dr. Judson Brewer, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist based at Brown University, he reminds me that part of what keeps fear alive is the pursuit of relief. I think of the relief as the comedown, the cooling part of the fever, as the poet Ada Limón describes in her piece “The Saving Tree”: when everything […] all of it, slows to a real nice drive by. Brewer, who studies mindfulness and the field of habit change, speaks of the symbiotic relationship between fear and worry (often employed as a means of coping with fear). I share that worry feels addictive to me at times, and he confirms, “Addiction is just an extreme form of habit.” Worry can certainly become an addiction. Referencing the avoidance theory of worry by Thomas Borkovec, which postulates that worry is reinforced in the mind by the belief that it is helpful, Brewer notes, “Worry becomes preferable to fear. Even worse,” he adds, “it feels productive.”

But this is faulty reasoning. Anxiety, or worry, is the mental equivalent of busywork: unnecessary, but superficially productive. In reality, worrying clouds higher-order thinking and etches itself onto our bodies. The more time we spend envisioning a catastrophic future, the more we convince our systems that it actually happened. I see this in my life. It’s like a taste for blood that I’ve never kicked. When I have nothing to worry about, I feel aimless, like being adrift at sea. What I seem to be attached to—as much as the actual worrying—is the sweet, sweet relief when something feared doesn’t come true. This is the true danger: in the end, most of what we worry about never happens; if you’re not careful, your mind can file this away—that delicious feeling of having narrowly escaped some terrible fate—as some perverse evidence of worry’s worth.

When your adrenal system and fear signals are properly functioning, that delicious feeling is well earned, not to mention accurate. Imagine that you’ve escaped a bear. You’ve safely made it to your cave. But now imagine that you start wondering whether every shadow is a bear. Even worse, the fact that there is no bear today no longer pacifies you. You want to know that there won’t be a bear tomorrow. Six months from now. A decade from now.

This is when what once was the solution becomes the problem. Not only are you frantically trying to hold on to sand, but you are telling a story about yourself, bit by bit, over years. Most of us start telling those stories as children. When I’m afraid, I fall apart. If I’m afraid, it means something is actually wrong. If I feel fear, nothing can be okay. I have to get rid of the fear whenever I feel it.

An expression I love: “The mind is always listening.” It’s why seemingly hokey things like positive self-talk and affirmations are shown to work. So if you need complete freedom from fear, present and future, you’re ultimately telling your mind that you can’t handle fear; that in fact, fear is crushing; that the only recourse is to never experience it. You are, in effect, reinforcing to your mind that something is indeed dangerous. We build our prisons and we build our freedoms. It’s as simple and as complicated as that.

(Exposure and response prevention would add this caveat: The mind is always listening, and it knows when you’re crossing your fingers. Meaning that the response prevention part of the therapy is even more important than the exposure part. Meaning that when you do an exposure—whether it’s in vivo or imagined—there’s a thousand ways to undo that exposure: quickly salt your sentence with a “God forbid,” ask your partner if you’re going to be okay. This is why there’s no such thing as a halfway-confronted fear. That’s just more testing, and the problem with testing is that you’re still looking over your shoulder, keeping half an eye on something; it just signals back to your brain that there is, undeniably, a threat.)

Exposure therapy, based on the principle of extinction learning by Ivan Pavlov, is lauded as the brainchild of Western psychologists. But you can find elements of exposure and response prevention across cultures throughout the centuries, from the concept of “refraining” in Buddhism to various traditions of drawing out pain (such as sweat lodges, forest meditations, and spiritual retreats into the self): to heal the pain, one must face it, sit in a room with it, call it by its name. The psychologist Albert Ellis—the founder of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy—based the model on tenets of Stoic wisdom, a tradition lauded by Seneca, who famously said, “There are more things … likely to frighten us than there are to crush us; we suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” This reminds me of a verse in the Qur’an where the devil admits, “I had no power over you except that I called you” (Qur’an, 14:22). Indeed, throughout the Qur’an and other holy texts, there are mentions of “whispers”: planting bad seeds; intimations.

Ecologically, many cultures have long turned to nature for fear cures. In Jerusalem, a Palestinian woman told me to rub sage on my chest and sit in water when I was afraid. It draws the terror out. Ancient poets have long turned to the natural world—rain, forests, oceans—for both metaphors and anecdotes about human turmoil and suffering. “Deep in the wild mountains, is a strange marketplace,” Milarepa, a Tibetan siddha, is quoted as saying, “where you can trade the hassle and noise of everyday life, for eternal Light.”

One autumn afternoon, I speak with Four Arrows (he also goes by Don Jacobs)—a professor of education and Indigenous worldview at Fielding Graduate University and a member of the Oglala Lakota Medicine Horse Tiospaye—and his friend and writing collaborator R. Michael Fisher, an artist and author of several texts on fear from an Indigenous perspective. When I share my experience in Jerusalem, Four Arrows says cultures all over the world know that sage draws out negative energy. “This is the property of the spirit in it,” he says. Four Arrows speaks of the Indigenous view of fear being one that seeks transcendence and interconnectedness. “Once an immediate fight, flight, or freeze response is chosen for good or bad, any remaining fear becomes a catalyst for practicing a virtue in the Indigenous way. Once action is taken, then one becomes fearless no matter the possible outcome.” He goes on to say that all animals, including humans, learn to manage fear in this way. “You are not the only intelligence trying to manage fear,” Four Arrows says kindly. “Insects, plants, animals—all have to learn to manage fear” so that it ultimately turns to fearless courage. He talks of taking our fear bodies into “environments that are not-fear based” so that we can learn how to turn fear into courage, patience, and honesty.

Instead of thinking of nature as existing in service of the “I”—which persists in that individualistic notion of the human (really, the self) as being central, as that which all else exists to serve—Four Arrows and Fisher speak of an egalitarian relationship between human and nature, in which one turns to the natural world attentively, with an eagerness to learn. “The problem with our understanding of fear,” Fisher notes of the dominant culture, “is that it’s fear-based itself.” The preoccupation with fear keeps it front and center. By contrast, he and Four Arrows speak of fearlessness as being the heart of the Indigenous perspective. Nature—the Earth and all its inhabitants—displays this, whether humans take note or not; take your terror to nature, Fisher says, and find “a field of care that is already fearless, not fear-based.”

This is a radically different approach from those that seem to use nature—as a device, a way to regulate your nervous system or calm down. Instead, this is a viewpoint that reminds us that we are already in relationship with nature, and allows us to be taught about fear. It reminds me of a quote in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s luminous Braiding Sweetgrass: “Knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the Earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.” It is love like any other kind: hollow when conceptualized as transactional or one-sided.

In one of his poems, Jalāl ad-Dīn ar-Rūmī speaks of the “night travelers” who turn toward the dark as a willingness to know their own fear. I started meditating a few years ago. For the first couple of years, I did it obsessively, a means-to-an-end habit buoyed by the app’s Australian voice and my frantic desire to find quiet. It wasn’t until this past year that I started to see how deeply I missed the point. Meditation doesn’t salvage us; it teaches us the worth of our own attention. Being willing to attend to something is transformative, and fear is no exception. As Brewer says simply, “Bringing awareness to fear changes it.” This makes sense. Bringing awareness to anything changes it. That doesn’t mean we should sit cross-legged for hours thinking about it; that would be more like ruminating on the fear. That sort of investigation is likely to be propelled by what Brewer calls “deprivation curiosity”—that sense of urgency that comes with wanting to fix something, vanquish it. Why am I afraid? How can I stop? This is the opposite of curiosity motivated by interest, by true mindfulness, which is the capacity to nod at something, inspect it, and then set it to the side to attend to the things that truly matter to you in life.

Only tenderness seems to do anything worthwhile to fear. Only patience and curiosity can give it what it needs to morph or leave or stay.

There is a verse in the Qur’an that reads, “We hurl the Truth against falsehood, and it knocks out its brain.” The best part of working with fear is the honesty. Meaning, it teaches you to be honest: honest about what you fear, honest about what you do to make it worse, honest about how willing you are to face it. Nearly a year has passed since I first pitched this essay. I’ve spent the months of the pandemic afraid and unsure of—what, exactly? My mind has been latching on to a carousel of fears: COVID-19, violence, breast cancer, writer’s block, infertility, the oncoming years of climate crisis, failure, myself. Even looking at this list makes me uneasy. The world feels precarious sometimes, so easily wrecked, and I don’t know how to forget that. Halfway through writing this essay, I realized something. I’d pitched it with the coy, subconscious desire for it to be a fear cure in itself. I was still seeking a trapdoor, a shortcut. Why not have it be this, my own writing? Maybe my research would lead me to some new, brilliant thing, some epiphany or trick.

There. My falsehood lies limply on the floor, its brains bashed in. What I’ve found instead is equally disenchanting and exciting: there aren’t shortcuts. The different generations and philosophers and prophets all seem to arrive at the same conclusion: square your shoulders and face the thing. Practice impulse control. Learn how to wait. Expose yourself to what scares you. Call upon the courage of your ancestors, the courage of the earth, and, if you’re so inclined, the courage of your past self.

If you let it, fear will erase you, but so will preoccupation with any emotion. Spend ten minutes with an addict and you’ll see the dark underbelly of pleasure. Just because something feels good doesn’t mean it is good. Fear feels terrible, but it isn’t necessarily so. What’s terrible is the place we give it on the mantel, the struggle and preoccupation, the resisting and pulling, the quick fixes. There is very little I can say with authority, but this I can: I have been afraid and accepted it, and I have been afraid and fought it. I think you know which was worse.

A few days before I need to hand in this essay, I find out I’m pregnant for the second time this year. Two days later, the doctor calls with the follow-up blood work. “It’s not good,” she says sadly. It’s either another miscarriage or another ectopic. I won’t know for a week. I won’t know until after the essay is due. My instinct is to push the deadline. How can I possibly write while in the midst of this fear? I want resolution. I want a neat ending, to be on the other side of the suffering. I start writing the editor an email asking for an extension. I’ll get to it in the new year, I think to myself. I save the email in the draft folder. The messy, unedited essay is still open on my desktop, and I reread what I’ve written so far. Then I delete the drafted email. Over the coming days, I type out my remaining thoughts. I edit the lines, combing through each sentence slowly. The sentences wash over me like a balm. It’s not a cure, but it’s something.

The other thing I’ve learned: don’t rob yourself of your fear. That’s part of you too. There’s a story of Milarepa one day finding that his cave has been taken over by demons. He tries everything. Lunging at them, pleading with them. Finally, he surrenders. He sits on the floor and sings, “It is wonderful you demons came today. You must come again tomorrow. From time to time, we should converse.” The demons vanish. In another version, he goes to the biggest, scariest demon of all and puts his head in her mouth. The demon bows deeply and disappears. I like that version best.

I’ve learned a lot about fear this past year. I’ve learned that it cannot be commanded and it cannot be fought. I would venture to say that’s because those are tactics you’d use against an enemy, and fear is not an enemy. It is an enflamed, bruised apple of an emotion, trying to ensure welfare and keep you alive. Only tenderness seems to do anything worthwhile to fear. Only patience and curiosity can give it what it needs to morph or leave or stay. You might have to agree to die and see what happens.

One of my favorite refrains is, What does freedom look like right now? What does it look like? Right now. For you. For me, often the answer is turning my attention to something actually happening; remembering that a wasted moment is solely one that isn’t lived, not one that is lived in grief or discomfort. Freedom is turning toward my body—the cadence of my lungs, the rivering lines on my palms—or toward the world around me, the clouds and trees, even my tiny desk plant that every day paws itself toward the sun. The crucial thing is to untangle true freedom from feeling good (or calm or pleasure). One can be free in the midst of terror. I’ve seen it. I’ve lived it. I don’t remember to do it very often, but I’ve done it, and each time I have, it’s been truly radical, like discovering a secret power.

This morning, an old friend calls. We speak about fear and healing. I try to explain to her what I’m starting to understand: “I keep forgetting. And then I’ll remember. And then I’ll forget again.”

“That sounds exhausting.”

“It is,” I half shout at her in excitement. “But here’s the crazy thing—I always come back to the same point. It doesn’t matter how many times I break my brain against an obsession. It doesn’t matter how many circles I go around. How deeply I forget or spiral. In the end, I always come back home. I always remember the same point.”

“What is it?”

I pause. I don’t know how to describe it. I remember that it’s the same tired thing. Costumed as another. That’s the wall you hit your head against at the end of the day: Oh, that’s right. You again. It’s like being afraid of a basement. It’s like avoiding the basement. It’s like building another house away from the basement. But eventually you have to wander down there. And when you do, you remember: Oh yes, it’s just the basement.

Another way to explain it is: You dream you are dying. Or you are plummeting through clouds the exact shade of your mother’s favorite lipstick. Or you are watching something terrible happen. And then, sometimes, you remember that you are dreaming.

Another way to say it is: You wake up. And when you awaken, you remember what it is to wake up, and you laugh at yourself for always forgetting. You laugh at yourself for forgetting, and maybe you love yourself for doing it too—how predictable, how human—just a little.

A Letter to my Husband

Struggling to explain her belief in God to her atheist husband, Hala Alyan reflects on her Muslim faith as inextricably linked to her family, to Palestine, and to histories of erasure.