Anna Badkhen is the author of seven books, most recently Bright Unbearable Reality, which was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award and for the 2023 Jan Michalski Prize for Literature. Her awards include the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Barry Lopez Visiting Writer in Ethics and Community Fellowship, and the Joel R. Seldin Award from Psychologists for Social Responsibility for writing about civilians in war zones. Her essays have appeared in New York Review of Books, Granta, Harper’s, The Paris Review, Orion, and The New York Times. Anna was born in the Soviet Union and is a US citizen.

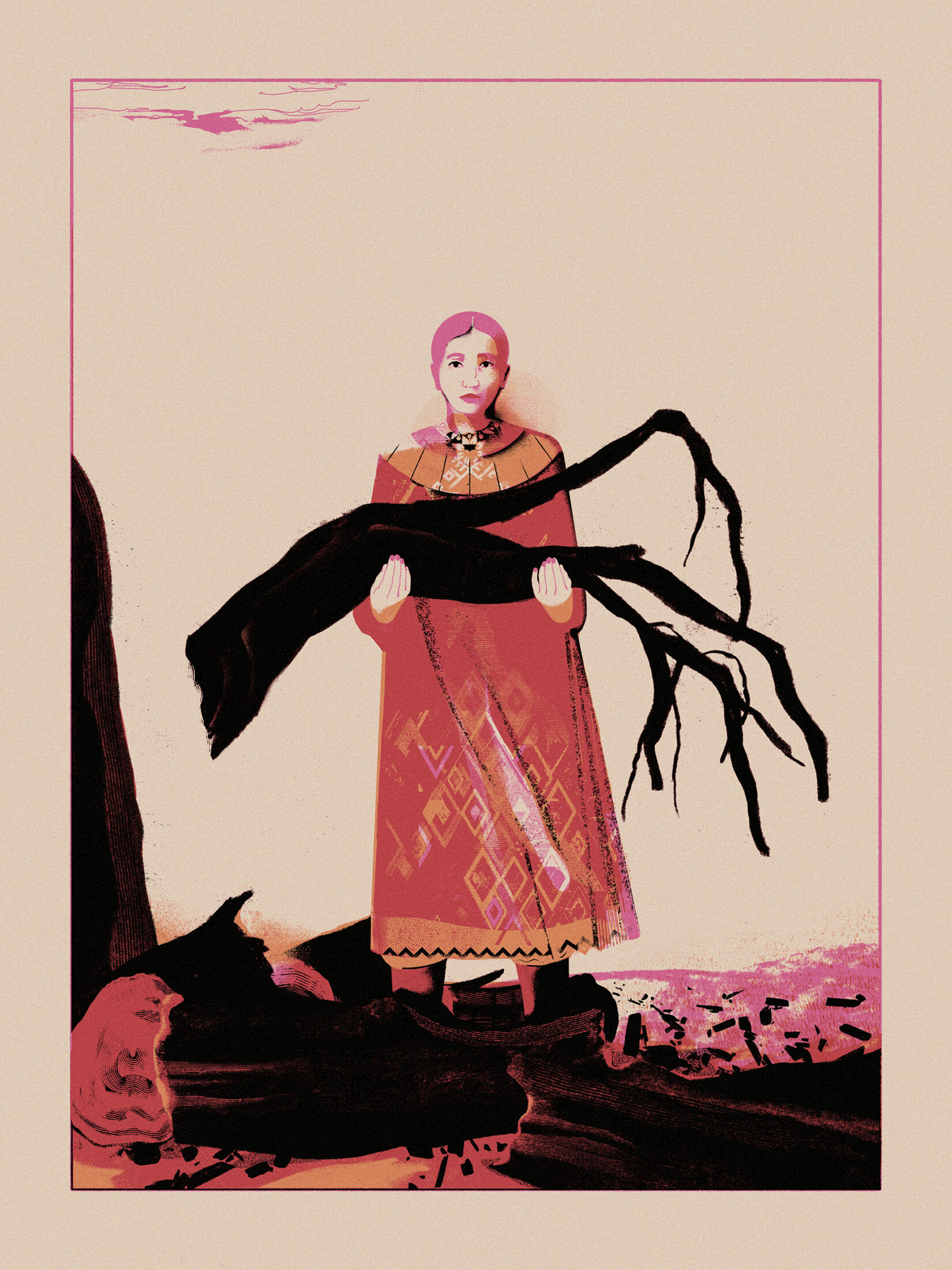

Juan Bernabeu is an artist and illustrator trained in Valencia, Berlin, and Italy. He communicates through line and drawing, using patterns and color to bring images to life. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Smithsonian Magazine, This American Life, and elsewhere.

Recalling histories of imperial collapse, Anna Badkhen wonders how we come to terms with the world we have made and how to make space for hope and sanctuary.

Human reason is beautiful and invincible.

No bars, no barbed wire, no pulping of books,

No sentence of banishment can prevail against it.

—Czesław Miłosz

Diourbel is an oasis in arid scrub brush about a hundred miles inland from Senegal’s Atlantic coast. Here, a century ago, the ascetic pacifist preacher Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba spent the last fifteen years of his life under house arrest for advocating nonviolent opposition to the French colonial occupation of West Africa. Today Bamba is revered as a saint and a hero of anti-colonial resistance, and the small slat shack to which he was confined is encased within a windowed marble shrine that stands roughly in the center of a massive sandy compound, which itself is surrounded by a tall white wall. You take off your shoes at the main gate, as you would entering a home, or the courtyard of a mosque. You pass through other, smaller gates in a succession of tin walls that partition the compound into smaller sandy sections, each quieter than the last. Then you reach it, the shrine, and through a window you can see the saint’s house, can see into the house.

For Bamba, Diourbel was both a prison and a place of creative flourishing. Here he wrote some of his twenty thousand devotional verses, and treatises on theology, Islamic jurisprudence, Sufism, religious sociology, and Arabic literature; here he fostered and directed the Mouride Sufi brotherhood he himself had founded on the principles of devotion and hard work. More than two hundred thousand people live in Diourbel now, but a century ago the town was a whistle-stop on the Dakar–Niger Railway, which the French were building to transport peanuts from the hinterlands to the port of Dakar. If I imagine gone the grandiose marble reliquary that ensheathes Bamba’s prison-shack, and the austere walls that surround his compound, and all the new homes built in Diourbel since his death, then what remains is a dun semidesert with a few trees to throw imperfect shade, and all around the kind of silentium ingens, quies magna that, I suppose, early anchorites sought out in the Eastern Desert of Egypt—Abba Agathon, who spent three years with a stone in his mouth to help him refrain from speaking; and Abba Bes, who “lived a life of the utmost stillness”; and Saint Gebre Menfes Kidus, an Egyptian monk who brought Christianity to Ethiopia, and who during his desert tenure lived among sixty lions and sixty leopards for so long he developed thick, white hair that covered his body like a coat. I think: in such quiet Bamba worked for fifteen years.

It was here—in this place, in confinement—that he envisioned, through the morality of his work, what would counter the degradation of the human spirit, and hoped into existence an entirely new, tangible place and way of living in devotion: the city of Touba, thirty miles to the northeast of Diourbel, a model of a perfect Islamic society, an autonomous city-state where all sin is forbidden and rigorous earthly labor coexists with religious scholarship, where the laws of lay governments do not apply, and where, since the beginning of its construction in 1926—a year before Bamba’s death—the population has swelled, so that it is now the third-most populated metropolis in Senegal. He also envisioned and designed Touba’s opulent Great Mosque, which the Mouride hold second in importance only to the Grand Mosque of Mecca. Whereas the Desert Fathers chose their desert solitude so they could focus on their relationship to God, powers of white supremacy forced the Sufi cheikh into his, and he dedicated it, barely half a century after the formal abolition of slavery in the French colonies, to imagining paths toward spiritual and cultural sovereignty for a people who would remain under occupation for decades after his death. I traveled to Diourbel because—like many pilgrims, I suppose—I hoped to see a place where hope was born.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear describes courage in the face of cultural collapse as “radical hope.” “Radical hope anticipates a good for which those who have the hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it,” he explains. “This is a daunting form of commitment: to a goodness in the world that transcends one’s current ability to grasp what it is.” Lear talks specifically about the predicament of the Crow Nation in the face of settler colonialist expansion in the United States, but also, more broadly, about the vulnerability of the human condition. Ruin, he writes, “is a possibility we all must live with—even when our culture is robust…. It is a possibility that marks us as human.”

Ours is the era of unprecedented man-made geological changes; of historically unmatched migration and concomitant fencing-in; a hyper-informed time when chronicles of one another’s lives are numbingly accessible yet our hostility toward one another persists; and when more people than ever in history are living alone. It often seems that we are on the edge of ruin. How do we hold on and what do we hold on to as we are continually coming to terms with the world we have made, are making, a place that contains both joy and hurt, a thaumatrope ever flicking between sacred and profane; and how do we honor and hold both the delight and the grief at a time of historical reconsideration? How can we soberly and responsibly counter despair, and dare hope for an emotional vocabulary against depravity? It awes me that Bamba transformed his confinement into a creative sanctuary, and I think it is no accident that the cheikh’s hagiography focuses on miracles of transformation: when his French captors locked him up in a cage with a hungry lion, Bamba prayed the beast to sleep; when they threw him in a furnace, he used the fire to make tea and invited the Prophet Muhammad to join him for a cup. There is something almost quantum about this kind of hoping.

I set out for Diourbel from Dakar, in a taxi. The June morning sky was white with haze that was part pulverized desert, part engine exhaust, and things appeared as stage flats, shadow puppets: the tinfoil sheet of the Atlantic; the cardboard cutout of a highway overpass on which a silhouetted horse dragged a cart toward a discolored market; the sudden goats staccatoing across the tarmac to disappear into the faded voile of thorn that trims the continent all the way to the Red Sea; the two-dimensional baobab, itself as big as a house, stapled with to-let notices. In such enchanted light, all had the air of a fairy tale, so that when highway patrolmen materialized out of the murk to collect tolls, swift and merciless, the taxi driver joked that they were latter-day roadside genies, that you half expected them to ask for your firstborn. But two hours into the drive, an egret atop a concrete police shelter unfolded to preen, and somehow, by the grace of its wingflick, the sky lifted and faint cirrus anointed the blue, and when a little past ten o’clock the taxi pulled into Diourbel, the hot air was still and brilliantly clear and held the place in a kind of reverent showcasing.

“There is a place,” writes Iris Murdoch, “… for a sort of contemplation of the Good … which is not just the planning of particular good actions but an attempt to look right away from self towards a distant transcendent perfection…. This is the true mysticism which is morality, a kind of undogmatic prayer which is real and important.” I walked through the compound barefoot on hot ochre sand, and stood before the marble structure that encased Bamba’s shack, and peered through the window. After my eyes adjusted to the crepuscle, I could sort of make out dusty things, a trunk with notebooks, a blanket, maybe a zinc washtub—I had read somewhere that Bamba often dumped all together into a washtub his correspondence and his receipts and the donations he received, either out of his detachment from worldly things, or perhaps to ablute them—and I stood awed by what these objects represented: the wickedness, the vision, the mystic rectitude of purpose.

How do we honor and hold both the delight and the grief at a time of historical reconsideration?

There is a spot in Bamba’s compound from which one can see neither the shrine nor the street; a tree grows there out of velvet sand. During my visit, under the tree on a mat there sat two old women and an old man who looked like they had been there since Independence. Their eyes were downcast, or maybe they were closed; I could not really tell. When I salaamed them, they remained absolutely silent, and I sensed that their company was greater than themselves, and I imagined that hope in its many forms—devotion, love, dreaming—bridged each in their fellowship not only with the suppliants to their left and right but with all the people who had hoped before them, who would hope after.

“Prayer,” writes Murdoch, “is properly not a petition, but simply an attention to God which is a form of love. With it goes the idea of grace, of a supernatural assistance to human endeavor which overcomes empiric limitations of personality.”

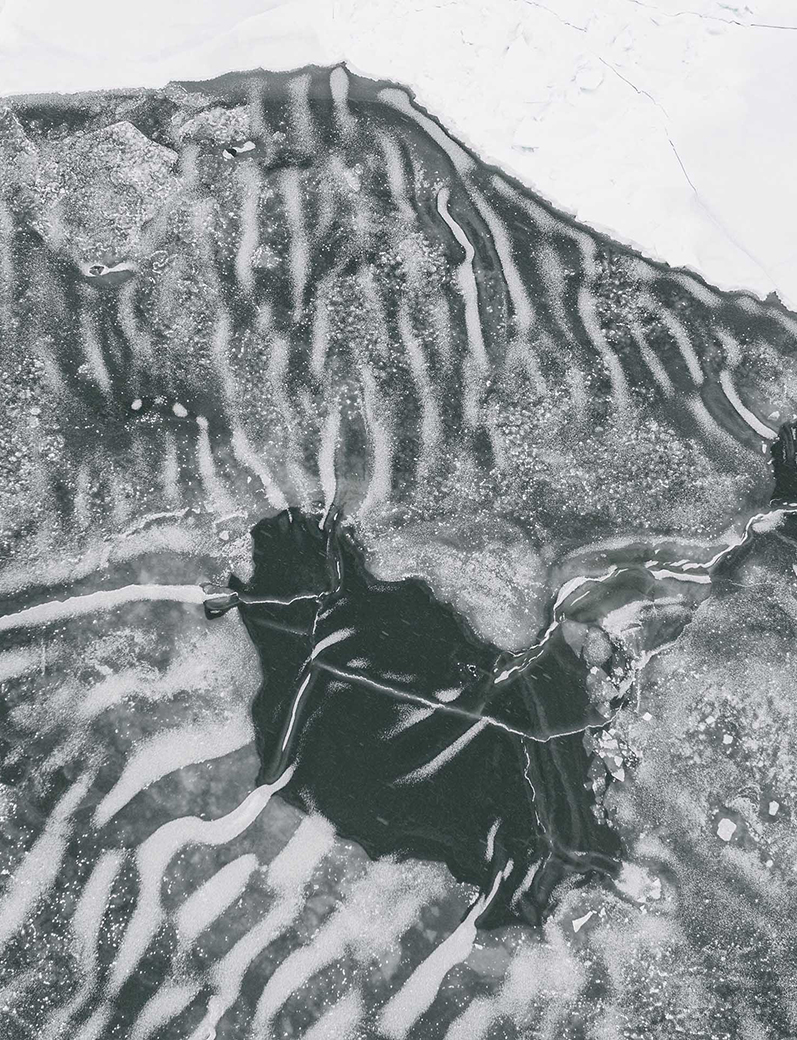

A few paces away from that tree I made a picture. It was the only one I dared to make at the compound. It shows a square patch of sand, nothing else. Traces of bare feet scallop the sand in subtle bas-relief, and overlaying their fine and intricate molding, the latticed shadow of the tree’s branches is pointing toward the camera. Everywhere in the compound sand gathers and spills in freeze-framed ripples, clipped waves. I have read that ocean waves result from both the disturbance of the water surface and the restoring force that calms the surface back to some primeval, nostalgically imagined stasis, and I wonder if, in addition to the wind and the bare feet of pilgrims that flatten and scoop the sand daily, there is a greater disturbance and a greater calming force at play in Bamba’s compound in Diourbel, a tension between discriminatory hardship and intentional prescient love.

In Judaism, one of the names of God is HaMakom, The Place. The ethicist Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, who preceded Bamba by a century, explains: “Just as a place supports and holds the thing that is placed inside it, so too does God support and sustain all the worlds and creations.” This is how sacred we make place: we name God after it. And look how much hope we vest in it, how we bestow it with a welcome, as a gift, or withhold it with a roll of concertina wire, at gunpoint; how we steal it and defend it and shed blood for it; how we displace or shut in one another for punishment, or change place because we feel it no longer supports and sustains us, or because we believe another place will hold us better—while all of us are evermore confined to a place we call Earth, which we at once embellish and besmirch. It is inside a place, and in relation to a place, that we learn to hope.

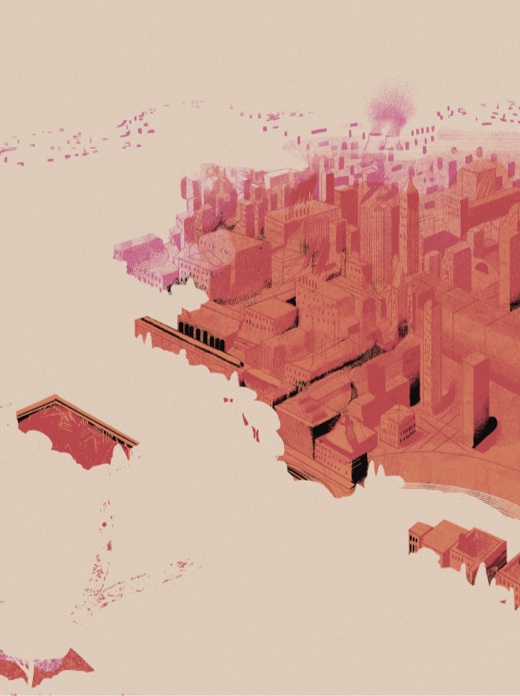

A satellite image of Diourbel shows a crescent of neat, reticulated lanes, the points aiming northwest. The street grid, the shape, and the direction of the tapering is the same as that of St. Petersburg, the city of my birth; I see the resemblance instantly, though the moment I think of it I recognize the absurdity of trying to connect a savannah town at fourteenth parallel north and a marshy seaport six degrees below the Arctic Circle. Maybe I see a likeness because it is a human impulse to seek patterns and see connections even when it feels like a stretch—or especially then. Poets do it all the time. Perhaps they recognize something essential: that similes are how we keep from feeling too lost in our dislocated world.

A memory filters in: My friends and I are thirteen, fourteen, fifteen in Leningrad in the late nineteen-eighties, trapped inside a pustulating imperium that is going batshit. There are ration cards and breakneck inflation and interminable predawn lines for bread and milk, and a confounded, malnourished, tubercular nation shrieks its anguish at demonstrations, lashes out at anyone alien, sometimes literally: one placard accuses extraterrestrials, They Ruin Our Footwear. Swastikas are everywhere. Soon Soviet troops will be murdering protesters in the Caucasus and the Baltics with tank cannons and bayonets, and soon thereafter the country will be no more, and the city of our birth will change her name for the third time in less than a century, and in the capital a new dictator will assume power, then another. Some of our parents join the protests, some hide axes under their beds for self-defense in case of pogroms. But we are too young, we cannot yet identify the symptoms of imperial collapse; all we know is that we want a sanctuary from the dread; we want to hope, to see beyond.

Hope, neuroscientists say, resides in the orbitofrontal cortex, one of the most confounding parts of the human brain, which somehow directs our decision-making and expectation and memory and emotional behaviors and our hedonic experiences—which is to say, what devastates us and what makes our life worth living. It is located just above our eyes: it dictates how we see the world. I wonder if this is why, to envision a hoped-for beyond or to focus better on a hopeful wish or a prayer, we close our eyes, or look up.

Up! And so up we run, as far up as we can: six or seven stories up the marble steps of communal staircases spray-painted with racist slurs and disembodied ejaculating cocks—up on crunching tiptoe through attics paved with granules of blast furnace slag—we push ourselves up and out through splintery dormer windows—we dance up the slight accordion of sheet tin until we are atop the crest of an arched glass-and-steel roof of an old atrium on Nevsky Prospect, above the city’s grand façades and Italianate right angles, so close to the enormous cold discus of the northern sky, looking down at our beautiful and rotten city, balanced just so on the margin between here and hope.

A month after my trip to Diourbel, I came across a photograph taken from the roof of the atrium in July of 1917. Another era of upheaval: the tsar has abdicated amid pandemic hunger; protests and strikes convulse the city; the Bolshevik Revolution is three months away. The photographer, Viktor Bulla, has run up to the roof and pointed the camera southeast, where from the sweeping curve of the National Library human shapes spill toward the viewfinder as if from a macabre capsized horn of plenty, scores of people running toward us—falling—dying—already dead under the fire of a machine gun, invisible from this angle, that government security forces have hidden in the neoclassical arcade of the building below.

What did the photographer hope for when he pressed the shutter? To hold the world accountable, perhaps; or maybe, simpler, to bear witness. Something, some intention, some expectation had been there, and also Bulla’s devotion to his craft. (The photograph would eventually fade from the Soviet press; Bulla, denounced by an informant as a spy, would be arrested and shot at the peak of Stalin’s purges in 1938.) In Lear’s book about radical hope, the philosopher asks: How should we live with the potential collapse of our way of life, not knowing what awaits? Hoping on a daily basis is difficult, especially in times of depravity. Maybe the trick is to hold on to something that astonishes, that urges us into some unfathomable beyond, that sustains our faith in the possibility of sanctuary, relief, change for the better. I think of the way Joseph Brodsky—he, too, grew up in this city, walked the same intersection, perhaps even climbed the atrium rooftop before the Soviet government forced him into exile—described the kind of poetry he admired: that it “answers not the question ‘how to live’ but ‘for the sake of what’ to live.”