Jori Lewis writes about the environment and agriculture mostly from the Global South. In 2018, she received the prestigious Whiting Grant for Creative Nonfiction for her latest book, Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History. She is also a contributing editor at Adi Magazine, a literary magazine covering global politics. Jori splits her time between Illinois and Dakar, Senegal.

Beth Moon is a photographer who is internationally recognized for her large-scale platinum prints. Her photographs are housed in collections around the world and have appeared in more than eighty solo and group exhibitions in the United States and internationally. Her books include: Baobab; Ancient Trees: Portraits of Time; Ancient Skies, Ancient Trees; and Between Earth and Sky.

Venturing out from her urban home in Senegal, Jori Lewis is drawn to the wisdom and resiliency of Africa’s baobab trees: ancient arks of biodiversity that have migrated across the landscape, enduring for millennia.

My husband always said he wanted to get married in a forest where a gracious African baobab tree could stand in as an altar. Could there be any more beautiful place, he asked, or any higher authority than that symbolized by a baobab’s numerous centuries of growth?

Baobab trees are built for benedictions, and for wonder, with their bloated trunks and short, spindly branches that scrape the sky in supplication. In dry climates like Senegal, those branches might be bare for much of the year, but when the rains start, a dense covering of dark leaves emerges and an oblong fruit with velour skin droops and swells. That fuzzy skin can be deceptive; if you touch it, hair-sized prickles can sting your hands like tiny shards of glass. At the base of a large baobab, I always feel such curiosity—about how many events it has witnessed, how much change it has withstood, how many generations of wanderers have touched or carved messages into its trunk.

But getting married in Senegal, where we live, is not like in the United States, where you can have a ceremony anywhere with the help of an officiant. Our best legal option here was to marry at city hall, where the deputy mayor presides over weddings, a few every day, in a room decorated with puffy signs and polyester flowers.

We live in the capital city, Dakar, a crammed metropolis that sits on a peninsula that bulges out into the Atlantic Ocean like an elbow. Its tip is as far west as west goes on continental Africa. In the mid-fifteenth century, Portuguese sailors steered their lightweight caravels down the African coast to cut the middlemen out of their commerce in spices, gold, ivory, and slaves. After a long stretch of tan desert, they espied the peninsula, a landscape so covered with palm trees that they were inspired to call it Cabo Verde, the Green Cape.

Ships at a distance would never give that peninsula such a name now. Trees are rarer than ever, and the city is beset by dust and fumes and overrun with concrete. It is only during the height of the rainy season that you can make out the whisper of what those Portuguese sailors saw. Then the peninsula starts to earn back its name: a green carpet covers the rocky cliffs; in the alleyways, leftover millet seeds sprout and grow into towering stalks; and cows return to the highway medians, drawn by the abundant grass. This lush appearance lasts only a couple of months, though, until an arid wind sweeps down from the desert, drying out the grass and then blowing it away.

A tree lover like my husband finds it difficult to live in the city. He does it for me, but only reluctantly, and only sometimes. He hates the colorful plumes of smoke coming from the parade of cars, the crowds of people jostling one another in the streets, and the incessant construction that chokes sidewalks and roads with piles of sand and gravel. He often comes home after a day out in the madness of the city with stories and photos of trees that have been sacrificed for new roads and of green spaces fenced off to make way for luxury high-rises. If I have to travel for more than a few days, he takes the dog and flees for calmer lands.

Our apartment is a respite from the assault, albeit slight. Here, he can spy a line of trees on our short street and momentarily forget the hostile environment of the city. When asked, he can cite all the different trees he can see from the balcony: a couple of neem trees; several nebadaye (Moringa), with their long, cylindrical seedpods; a ficus or two; a flamboyant blanc; a gray-leaved Cordia; a few fruit trees—mango, papaya, and sapodilla; a whistling pine tree; a coconut palm across the street; a frangipani with pink flowers that sweeten the air; and, just behind a fence, a generous baobab tree.

Botanists say that the baobab is one of the largest known succulent plants. When I share this tidbit with my husband, he’s not surprised. He says, of course, the baobab tree is mostly water, just like us humans.

The African baobab comes from a relatively small family of cartoonish trees: six species native to Madagascar, one to Australia, and the one that occurs across continental Africa.

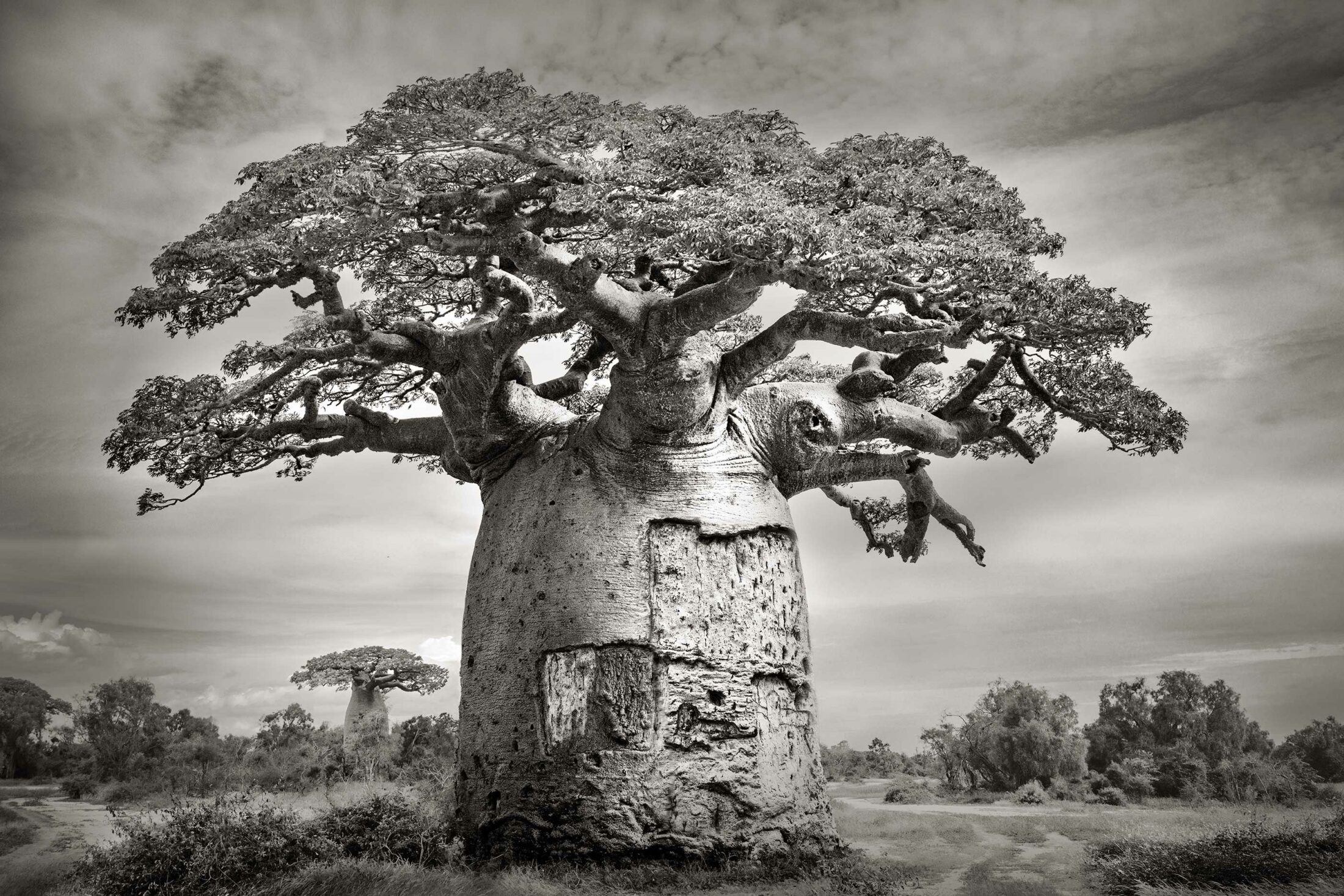

The baobab’s genus, Adansonia, was named after a French botanist who described the baobab in the mid-eighteenth century. Michel Adanson was out hunting near the main French trading post in northern Senegal, and while concentrating on hitting some large gazelle between the eyes with his musket, he espied a wondrous thing: a tree with a mind-boggling girth. Having no instruments with him, he tried to measure the trunk with his arms. “I walked around it thirteen times, stretching out my arms as far as I could; and for greater accuracy,” he later wrote in his influential tome, Histoire Naturelle du Sénégal. “I then measured the circumference with a string, and found it to be sixty-five feet; its diameter was consequently nearly twenty-two feet. I do not believe that we have ever seen its like in any other part of the world.”

Adanson asked his guides about the tree and was told that they called it goui in their language, Wolof. He said they also sometimes called it the monkey bread tree because the resident primates were especially fond of the sweet, sour fruit and would slam the pods on the ground to get at the whitish, powdery flesh inside.

The Frenchman combed through some readings and found that the fruit of this tree had been described by European naturalists at least two centuries before his own chance observation. The first was a Franco-Italian scholar called Julius Caesar Scaliger who obtained a baobab fruit that had come from a Portuguese settlement in East Africa and described it in a paper published in 1557. A few decades later, the Venetian physician Prospero Alpini saw the fruit in a Cairo market. He described and sketched its form in his monograph on Egyptian flora, De Plantis Aegypti Liber. Alpini called it the ba hobab, a name that Adanson adopted in his first exhaustive description of the tree in 1757, which he submitted to the French Academy of Sciences. Adanson did not know, or did not care, that other visitors, like Ibn Battuta and Leo Africanus, had described a tree that sounds like the baobab even earlier.

The taxonomists could have used goui or ba hobab or any number of other names, but they (with intervention from Carolus Linnaeus himself) ascribed Adanson’s name to that tree and all its relatives.

The tree that all of these men described was the African baobab, Adansonia digitata, the most common and widespread species of baobab tree.

“This tree is a godsend,” plant biologist Lamine Ndoye told me. He is an instructor at Dakar’s Cheikh Anta Diop University and studies the genetic diversity of Senegal’s baobabs. “People used to plant these trees for their everyday needs because they were useful for so many purposes: they were used for ropes, for medicines, for livestock feed, and for human food.” One group of researchers found that the baobab tree has at least three hundred uses in towns and villages across West Africa.

Baobab trees are built for benedictions, and for wonder, with their bloated trunks and short, spindly branches that scrape the sky in supplication.

Even in our urban household, the baobab makes regular appearances. In the mornings, I sometimes add a spoon of baobab fruit powder to my oatmeal. It adds a tangy-sweet flavor to the oats, as well as a good dose of vitamin C and calcium. For lunch, my husband likes nothing more than ceere, a millet couscous to which is added laalo, baobab leaves pulverized to a fine powder, a much-needed emollient for the dry, sandy grains. And before bed, I often use a cold-pressed baobab seed oil on my face, a nighttime treatment to combat the ravages of the sun and the dry winds that blow from the desert during the dry season.

Some researchers have hypothesized that the tree followed human populations, noting that a grove of baobabs could mean that a settlement was once nearby. In Senegal, specific baobab trees often served as palaver trees, a kind of informal town square where leaders and their people would talk about how to govern. But village settlements alone can’t account for how widespread baobabs are, according to University of Wisconsin–Madison researcher Nisa Karimi, who explained baobab dispersal to me on a Zoom call. “We know humans have moved them around, but based on the continental scale, it’s probably more likely that baobabs colonized the continent and people moved them, here and there.” Instead, it may have used its own wits and wiles to travel to the four winds by enticing rhinos and baboons, elephants and elands, with its sweetness. As they ate its fruit and moved around, trees sprouted up in their scat, a trail of life in their waste.

After all, researchers think that baobab trees evolved millions of years before humans were even a speck in some ape’s eye. They are survivalists on a geologic time scale; they were around when the Sahara was a lush grassland and the Congo Basin was a semi-arid desert, and they have weathered one ice age after another. It seems likely that people followed the baobabs, not the other way around. It is, perhaps, our hubris that puts humans at the center of the tree’s evolution.

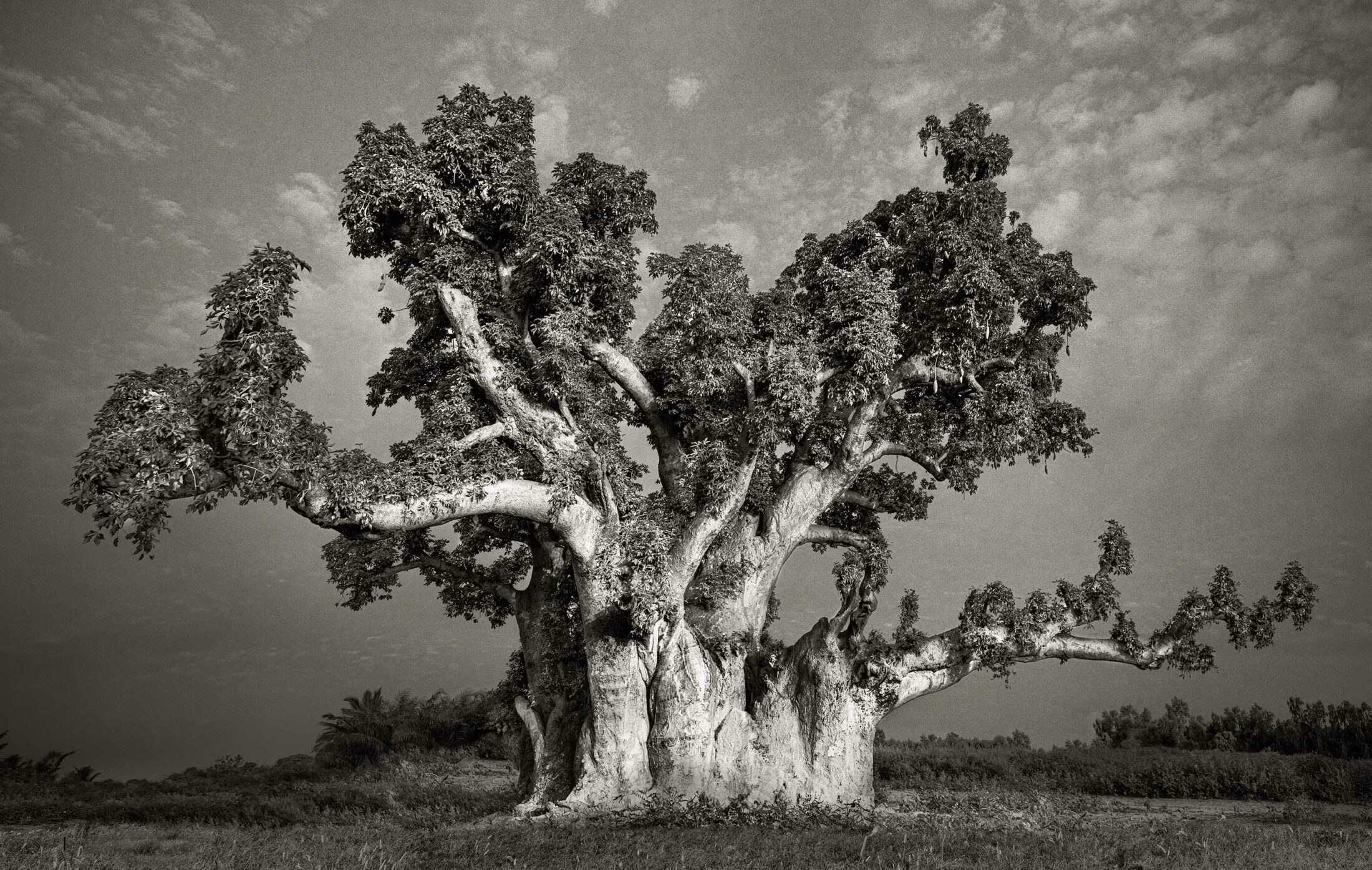

When I leave Dakar to go to my husband’s hometown, Mbour, which is about a hundred kilometers away, the highway winds through a forest of brush, Sodom apples, spiny acacias, and corpulent baobabs. The baobabs are especially dense here and dot the horizon as far as the eye can see in a concentration rarely encountered. The trees’ appendages are skeletal and deformed from decades of leaf cutting, which has altered their canopies in ways discernible only when you see a baobab with a full head of thick and lustrous leaves. All around: dried grasses, weathered to tan, gold, and brown by turns; flashes of dark green—well-placed carpets of shrubs decorating the soil; coppery ribbons of donkey paths, undulating through the savanna.

This forest is in a sparsely settled rural community called Nguékhokh, a name that in the Sereer language suggests it was once a place where one could take shelter or hide. Historians have suggested that it was so named because it had long served as a place of refuge for people in need of it. The generous baobabs gave their leaves, their shade, and their fruits. The largest of baobabs have hollow cavities that could have served as hiding places for those who were passing through—those who did not mind the trees’ other dedicated denizens: the bats, the monkeys, and the spirits.

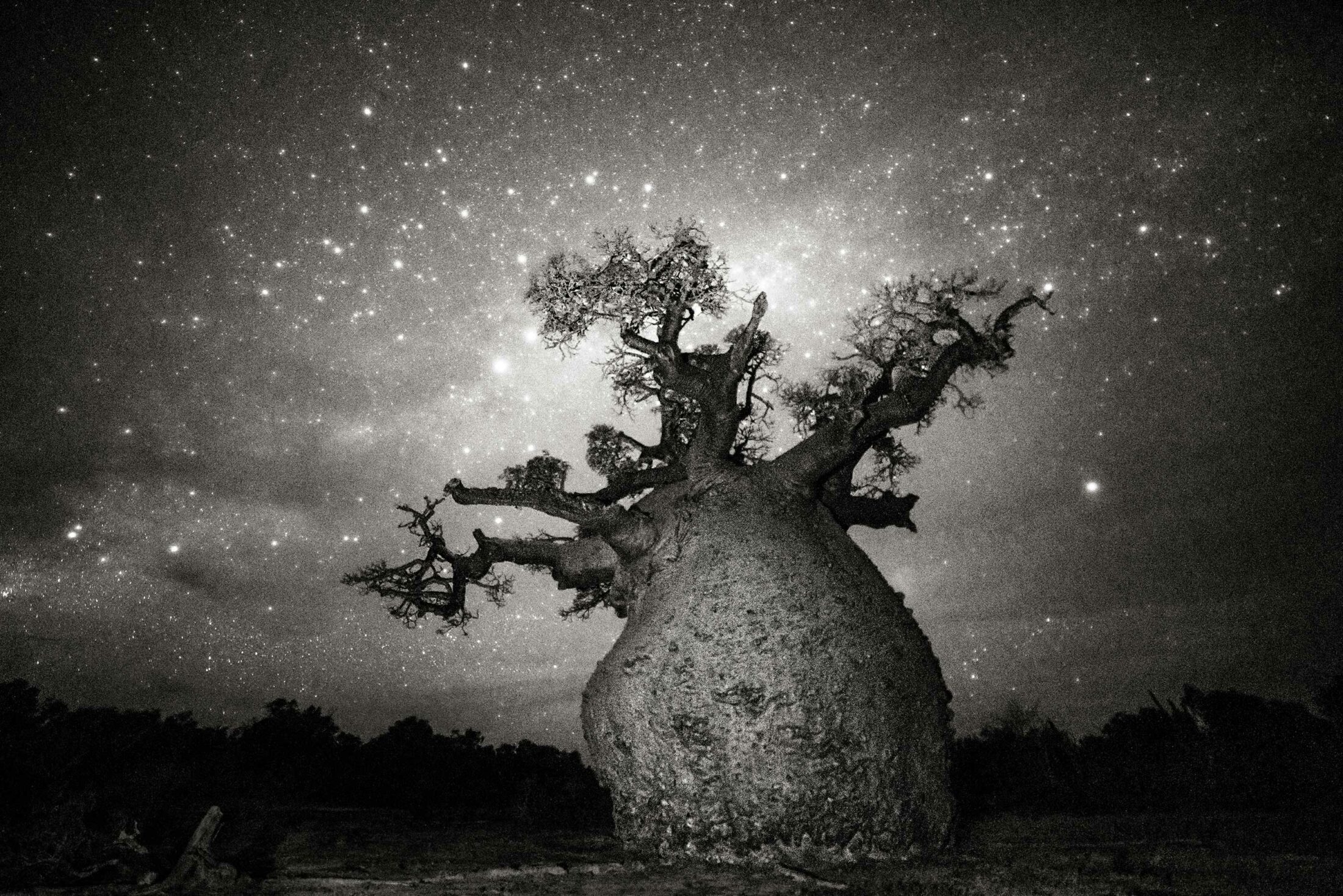

Baobab trees are thought to be the homes of spirits par excellence here, a belief that is shared in many places across Africa. Maybe they got this reputation because their steady presence in communities and their slow rate of aging make them seem eternal? Baobabs are veritable Methuselahs who, in the best conditions, can live for more than two thousand years. Imagine, two millennia in one spot? Human generations are calculated in twenty-five-year intervals, so such baobabs would have witnessed eighty generations of humans crying as infants, crawling, growing, living, exploring, farming, building, warring, loving, and dying. Throughout, the trees remained—steadfast and rooted. How could people not see such beings as ancestors, as holders of secrets from the great beyond?

I can only trace my family back for five or six generations, to a few enslaved individuals whose records we have found. Those documents don’t tell us where in West or Central Africa their parents or grandparents or great-grandparents might have lived and loved and died if their lives had been different. Now that I live in West Africa, have I ever walked in their footsteps, their memories grooved into the soil, the rocks, and the forests? Have we held our hands to the same old tree?

A scientist recently published a paper describing a novel mite species from the Metagynella genus for future taxonomists. The mite was found in a sample of a decaying baobab taken from Senegal in the 1970s and hereafter stored in the Museum of Natural History in Geneva. This scientist eschewed personal recognition in naming the mite, instead calling it Metagynella pangooli after the ancestral spirits and saints of the religious tradition of Senegal’s Sereer people. The word pangool refers to those spirits and the physical places they inhabit: a bit of forest, a marsh, a rock, a gentle hill, or a tree with a broad trunk. Even a scientist could see that the baobab keeps company with the divine.

When I read about this mite, I wondered how often it was that baobab trees died. They are the trees of life, the immortals. But, of course, all living things die, eventually.

And the oldest baobab trees seem to be dying more and more these days. According to researchers who radiocarbon-date big trees, nine of the thirteen oldest African baobabs that they had studied have died or have had their stems collapse since 2005, including one that was 2,500 years old. “The deaths of the majority of the oldest and largest African baobabs over the past 12 years is an event of an unprecedented magnitude,” the authors wrote in an article published in the journal Nature Plants. They suggested that the climate might be to blame—especially changes in rainfall in Southern Africa, where all the trees that they included in their data set were located.

I wonder, though, if flashy headlines about climate change affecting the oldest baobabs have caused us to ignore what is happening with the youngest ones. Old things often die, but maybe the bigger problem is that new baobabs are struggling to grow.

In the Nguékhokh forest, a report from the early 2000s found that most baobabs there were well into their middle age, between five hundred and a thousand years old. The authors noted that the forest had few young trees. The situation in Nguékhokh is mirrored across much of Africa, from the Swahili coast of Eastern Africa to the veld of Southern Africa and the upper savannas of West Africa. And this is not a new observation. In 1906, French botanist Auguste Chevalier noted: “The Adansonia are indeed endangered trees; even in the bush and savannas where centuries-old baobabs are still abundant, it is extremely rare to find stands of young trees.”

A living forest should be both old and young, but the baobabs across the continent are always aging, and sometimes dying, and few have young saplings ready to take their place.

Imagine, two millennia in one spot? Human generations are calculated in twenty-five-year intervals, so such baobabs would have witnessed eighty generations of humans crying as infants, crawling, growing, living, exploring, farming, building, warring, loving, and dying.

A friend in Senegal once told me how, when he was a child, his mother would not let him play at the end of the street because an older woman lived there, one who had never had a child. I can only speculate about what fears his mother had about that childless house at the end of the street. Was it that this woman’s childlessness, her perceived infertility, could attach itself like a stain or spread like an illness? Or was it something darker? Did she see that childless woman as a witch, as a monster? Did she think that woman was childless for a mystical reason? A punishment? A curse? Or did she believe that the woman ate her babes like the old crones in the tales? This fear of the crone, I suppose, exists across cultures. I did not think then that any of it was relevant to me.

When I tell my older sister about trying to get pregnant, she sympathizes but does not really understand. She fell pregnant at twenty without trying at all, and, in fact, was trying to avoid it. It was so easy for her to get pregnant—too easy—all those years ago. But I’m at the other end of the reproductive-age spectrum, and trying to conceive later in life has made me realize how much luck is involved in the process.

Last spring, I, too, got pregnant after not too much trying. We found out early, and I went to the doctor to confirm the pregnancy with an ultrasound. It was too early to see the heartbeat, so I made an appointment to come back a few weeks later. My gynecologist printed out a photo of our little embryo, and I showed it to my husband later. We were so excited—making plans, picking names. Ever a planner, I downloaded no fewer than four pregnancy books on my Kindle, and I started searching for a doula in Dakar.

My husband got into the nurturing phase too. He was away in Mbour and had discovered that a female hedgehog had given birth in the garden and then died. He decided to nurse the baby hedgehogs himself, swaddling them in a basket and feeding them egg whites with a tiny dropper. I thought, It’s a sign that he’s ready.

On the next visit to the doctor, though, the doctor told me the embryo had stopped developing. In the early stages of pregnancy, the embryo’s cells are supposed to be dividing all the time, and the embryo should be experiencing exponential growth every week. But mine was still about the same size it had been during my first visit. And, crucially, there was no heartbeat. The rest is predictable. I took the pills she gave me that same day and cried and cramped and hemorrhaged throughout the night.

My husband was still away in Mbour the day I discovered this, that our happiness was so fragile. And even though he redoubled his efforts with the hedgehogs, one by one they died too.

It is possible for a baobab to reproduce in nature, but for it to happen consistently, and for true regeneration to occur, a lot must go right.

The bats living in and around baobabs are key to the trees’ reproduction. Baobab trees have what biologists call classic bat pollination syndrome, which is to say they have a series of traits that make them irresistible to bats. Their bell-shaped white flowers start to open only at dusk, just as the nocturnal flying mammals are waking. The petals start to open and expose the flower’s stamens; the flower emits a seductive musky scent, guaranteed to entice even the most reluctant bat into its waiting arms to look for nectar. In the bat’s delirious haste to slurp up its plant ambrosia, it will cover part of its body with pollen, only to be soon lured by another heady scent on the wind: the next baobab flower beckoning in the night. In this way, the bat mixes the pollens from some trees with different trees and facilitates fertilization. Each flower is receptive for just one night, so if the bat or another pollinator, like the hawk moth, misses it, they are both out of luck.

It takes about five months for the fertilized flower to turn into a ripe and ready fruit, dangling from a branch throughout a good part of the dry season. Once the fruit is mature and harvested by a person, an ape, or another animal, or shaken free by the wind and rain, it’s now time for the second phase in its reproduction.

Baobab seeds are covered with hard shells that are both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, such protective coverings can insulate them from the bush fires so common in the savanna, allow them to pass through an animal’s digestive system without being completely broken down, and shelter them from the solar pounding that an exposed seed might experience in the long, dry months before the rains come. But on the other hand, the hard coating is impermeable, preventing water from getting into a fresh seed so that it can germinate. The seeds need a lot of time for the sun, the heat, and the rain to dissolve their natural defenses so that they can take root and grow.

If a person wanted to plant a baobab, though, and was determined, there are manual ways to, as scientists say, “break its dormancy”—to snap it awake. You could soak a seed in sulfuric acid, mimicking the digestive system of an animal; expose the seed to high levels of dry or wet heat; or, easier still for the low-tech among us who don’t happen to have acid or hot ovens at their disposal, nick it a bit by poking a little hole in the covering or shaving part of it down. Each method could help the water get inside and signal the seed to start to grow.

Once the seed has germinated, it starts developing its water-absorbing taproot and begins to push its leaves out to the sun. Still, a baobab seedling grows relatively slowly. One recent study showed that in the first month of growth, a baobab seedling grows no more than eight leaves; in its first two years, it grows less than two meters.

Fully grown baobab trees have an incredible ability to absorb and store water, so they can wait out the long, dry months and produce leaves and fruit. This water weight can cause the circumference of the tree’s trunk to fluctuate between the wet and dry seasons, its body’s ebb and flow. But seedlings are more vulnerable to the droughts and the fires, to the animals and the plows. In another study from South Africa, the researchers found that 95 percent of young baobab seedlings died from lack of adequate rainfall. Some of those that survived that first season were then uprooted as farmers cleared their fields, or they were eaten by livestock.

Even after it establishes itself, the baobab must undergo a long period as an immature juvenile before it is capable of reproduction. In the best of cases, it takes baobab trees about twenty years to flower and fruit so that they can start to bear offspring, but some researchers have speculated that baobabs in especially dry environments could take more than two hundred years to flower.

There are so many possible ways for the baobab’s reproduction to go awry: if the drought goes on too long and the tree doesn’t fruit; if the seeds drop into fertile ground but never germinate for lack of rain; if, even when it grows, the animals eat too many of its shoots; if a wildfire rises up and burns the young tree; if thirsty elephants take a bite out of its water-filled trunk; if the baboons, for lack of other food, start eating unripe fruits with seeds that, even if dispersed, won’t germinate; if the tree waits two hundred years to flower and finds itself in a landscape so changed that the bats or hawk moths have started to migrate before the flowers open; if, if, if.

How could people not see such beings as ancestors, as holders of secrets from the great beyond?

Every biologist I spoke to about the baobab—researchers in the US, Europe, and across Africa—said that, of course, human-made climate change threatens the baobab. But so does overgrazing, excessive harvesting of its leaves and fruits, and the changing ways we use the land. Those man-made crises for the baobab are even closer at hand.

On a recent trip through the baobab forest of Nguékhokh, I stopped the car on the side of the highway to take a picture of a larger tree, one that stood out among its brethren—a bit fatter, its branches a bit more balanced, something poetic about its stance. As I got closer to it, I saw a sign tacked to its trunk: terrain à vendre (land for sale). This particular forest isn’t protected land, and people need houses and schools and roads like the one that made my trip possible, the one that plowed through the middle of this forest. This picturesque baobab in its prime—remember, at least five hundred years old—may not be long for this world.

Some years ago, before I knew him, my husband and his siblings were building a house for their mother on a property they acquired a couple of hours from Dakar. There was a small baobab on a corner of the property, and he, tree lover that he is, worked with an architect friend to develop a building plan that would respect the baobab and even allow the inhabitants an opportunity to commune with it. This connection was to be most visible on the second floor, which would include a terrace that would caress the baobab’s canopy. “I wanted the baobab to be there, inconspicuous yet present,” he told me.

The house was to be built in stages, as is so often done here. Once the first floor was done, his mother moved in, and the family planned to construct the second floor later. But almost as soon as she moved in and started getting visitors—friends, family, and neighbors too—the plan started to change.

“They said it wasn’t safe to live with a baobab, because it’s a haunted tree,” my husband recounted. Soon, his mother started to change her mind about living with the baobab tree, and a consensus among the siblings emerged (except for my husband): the baobab had to go.

Turns out that if you want to cut down a baobab tree in Senegal, you must first call a sage. There is no written law on the books about this procedure, but most people know not to skip this step. The sage does not cut down the tree himself but consults with the spirits who, for decades or centuries or millennia, have found shelter there. What will it take, he asks them, to find a new home somewhere else? What price, what motivation, what carrot or stick, will make them leave their tree? Usually, the spirits agree to leave with just a bit of cajoling and an offering of wine or some milk, a bit of millet, or even an animal. Here, the sage told them to kill a goat and pour its blood at the foot of the tree, but my husband said he does not know whether or not the others did that.

Two different workers had at it. The first got sick; maybe it was the spirits? Another was able to finish the job by taking his time and stripping the trunk a bit every day, unraveling its decades of life. Now there’s a baobab-sized empty space on the property, and my husband remembers the tree with nostalgia: its curves a rest for the eyes; its branches a home for crawling critters, birds, and bees; a whole world gone for good.

Once a baobab tree is cut down, its wood is something close to worthless; it is impossible to build a fire with it or use it to make wooden furniture or shingles. That’s because, when cut off from its source of life, the baobab’s bark gets soggy, and if you squeeze it, water will drip from it as if from a sponge. The market can accord little value to its dead body; the real value of the baobab, by any metric, is in its ability to live.

I had always supposed that since six of the eight species of Adansonia were native to Madagascar, the big island off the coast of the African continent must be the genus’s center of origin. It seemed like the obvious story: a family of trees, happy to live and evolve together until one or two of them decided to cast their seeds farther afield. Indeed, this has long been the general opinion.

But when we dig down deeper, other possible stories start to emerge. The closest living relatives of the Adansonia genus are native to South America, says Nisa Karimi, who is also working on a project to map the genetic characteristics of baobabs. “The current estimates of the date of divergence of the baobabs from their living ancestors are somewhere around the order of forty million years,” she said. “So obviously, a lot has happened since then.”

There are a few hypotheses about what happened next, all involving a buoyant seedpod floating across the oceans. One of them does include passage through Madagascar, via Antarctica, Australia, and the Indian Ocean. Another theory has the ancestor moving itself up through North America, into Europe, and down into Africa. And yet another theory suggests that a seedpod from one of those South American candidates hitched a ride on the Atlantic currents and washed up somewhere in West Africa. This is the one I like the best. According to the theory, the ancestor of the genus evolved there—let’s call it the protobaobab—about ten million years ago and moved across the continent. Eventually it crossed other oceans and spread to Madagascar and Australia.

At some point—everyone accepts this part—there was a glitch in the cell replication of a developing seed and it created a new thing, a tree with twice as many sets of chromosomes as the others—four instead of the usual two. That glitch led to the only tetraploid of the genus, Adansonia digitata, or the African baobab, which diverged from its ancestor about six to ten million years ago. “There’s sort of this hypothesis that if you have multiple copies of your genome and you have multiple copies of individual genes, it almost allows for more flexibility, if you can think about it that way, for adaptation,” said Karimi. She thinks it is possible that A. digitata’s tetraploid nature is why it could adapt to so many different environments across Africa and develop the skills to survive from Senegal to Sudan, from Nigeria to Zimbabwe, absent only from the continent’s extremes, the rainforest and the true desert. That adaptability must be a good sign for the future, even a future as uncertain as our planet’s.

In the past, during times when the climate changed—when a wetland went dry, when the drylands flooded, or when the temperature oscillated—this adaptable baobab may have been able to survive in environmental islands. The population may have contracted to certain niches, “refugia” to the scientists: on the rocky slopes of a mountain where the air was slightly cooler, in a depression where an itinerant rain’s flow might be concentrated, on a peninsula where a microclimate could keep the trees from the extremes of the continent. These were places to hide out from the tough times, places of refuge.

Once the crisis had passed, individual trees remained in place, but their offspring marched forward and headed out from their environmental islands. They were their own arks of diversity, ready to populate a changed world. Dispersed by their animal friends or the rivers and streams, they walked to new grasslands, hills, and valleys.

If I knew where the best refugia could be, I would head to those places right now with a bag of baobab seeds in hand, determined to get a jump start on the apocalypse. One of those seeds might become the flexible tree that outlasts eighty more human generations and lives to tell the tale, written in its body.

Just before Christmas, my husband and I went to stay with his mother in the village where she now lives. A famous baobab lives there too. According to the local lore, this particular baobab can help a woman become pregnant—if she does a special ritual. I wanted to visit the tree, not for the ritual, but because I had heard that it is one of the largest in the area.

We headed to see the tree on Christmas morning while the children of the house were busy playing with their new games and toys. We headed past the church, where the faithful had assembled for Christmas that morning in their best clothes, past the school, past the market, across a creek where our car slipped on a sandy path made slick by the water and swung to avoid a horse cart. Past informal dumps with plastic bags and wrappers everywhere, confetti worked into the sand.

Standing before it, I marveled at the sheer breadth of the tree, although, unlike Adanson, I did not attempt to measure it with my arms. Instead, I tried to get enough distance to take in its full measure, from its base to the tips of its branches, but was hemmed in. The tree was once on the village’s outskirts, but the town grew around it, and it is now surrounded by houses in varying stages of completion.

The tree had seen better days; on one side, the termites were having their way with part of a stem, building their mound higher and higher; and the tree’s branches were patchy, mutilated not long ago by herders in search of forage for their animals. At least that’s the story according to the man who waited near the tree, eager to guide any stray tourists from the nearby resort who might venture into the village. At his insistence, we decided to climb over the tree’s legs and creep into its stomach, a hollow interior with room for at least a dozen people. After he told us that the baobab and the banana were closely related (they aren’t), my attention shifted and I let his voice recede like a distant sound in the wind.

My eyes adjusted to the sudden darkness, and I tried to locate the bats that I heard squeaking and singing in the eaves—yes, a choir of bats—and I realized that this tree felt like a church. And I was in its sanctuary having my own silent service, praying without knowing it. The bark was a rough skin; I touched my palm to it to feel its coolness, the water of life running through its veins.