Jake Skeets is Black Streak Wood, born for Water’s Edge. He is Diné from Vanderwagen, New Mexico. His debut collection of poetry, Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, was a winner of the National Poetry Series and the American Book Award. He won the 2018 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Contest and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His honors include a 2020–2021 Mellon Projecting All Voices Fellowship and the 2023–2024 Grisham Writer in Residence at the University of Mississippi. His research explores Diné poetics and aesthetics, ecopoetics, Indigenous queer theories, and critical Indigenous feminisms. He currently teaches at the University of Oklahoma.

Bear Guerra is a photographer whose work explores the human impact of globalization, development, and social and environmental justice issues, often in communities typically underrepresented in the media. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Le Monde, BBC, and NPR, and has been exhibited widely. He was a finalist for a National Magazine Award in Photojournalism. Bear and his wife, Ruxandra Guidi, work together under the name Fonografia Collective to produce local and international print, radio, and multimedia stories about human rights and social justice. Bear is also a board member and producer with the award-winning nonprofit journalism collaborative, Homelands Productions, and is the visuals editor at High Country News.

Summoning the experiences that have shaped his relationship with food and nourishment, Diné poet Jake Skeets puts forth story as a pathway to food sovereignty, reminding us that memory and history are deeply enfolded in the meals we share around the table.

I rattled with the truck as my family and I drove a short way to the corral to get the sheep. It had been donated to us to help feed the many who were scheduled to show up later in the day in celebration and reverence for a relative who was reaching a pinnacle in her/their life: the Kinaałda, or what has been loosely translated as the Diné puberty ceremony. An intense and refreshing four days of family, song, and food. The ceremony is a moment when beauty of the beyond and beauty of the world come together as we sit around a fire and grind corn, tell stories, and prepare food.

As we rolled up to the corral, my mom was worrying because there was no one to do the butchering. Butchering for ceremony takes a tremendous amount of labor and often requires several people. She had called everyone in our family, even distant family, and I had posted on social media asking for anyone who might happen to be free. But no one responded. There is no blame here. Times change, pressures build. We are often pulled in so many directions. I told my mom we had to do it ourselves. Uncertain, she agreed, and I would do it.

My role in these ceremonies has slowly begun to shift. I’m no longer a child who simply witnesses but an adult who must participate, and as such it’s important to enter the space with the proper mindset. We don’t think negatively or with anxiety during the next four days. We don’t hesitate or feel unsure about our roles and duties. We enter the space with a lean toward what is beautiful in the world, what is right and balanced. Even writing this essay, I feel compelled to focus on what is working rather than what is not working, because you don’t pair a ceremony like this with more negative assumptions. It is beauty way. It is hope. Some might call it a naïve optimistic hope, but I call it a critical hope.

As a child, I remember these kinds of ceremonies often being well attended; many of our distant relatives would travel to our home and we to theirs. My aunts and grandmothers from all across our family tree would work together to butcher. We would help wherever we could, learning what we could and participating in the continuation of our culture. However, time brought us forward, and now my parents are grandparents and families are growing distant, meandering through the thickets of existence in the what-might-be end times. Much of Navajo consciousness has been focused on the idea of language and culture loss, with each generation finding less to hold on to. I remember first hearing about language revitalization and cultural integration as a child in elementary school. How do we sustain our Diné way of life? Of course, we don’t think about that or comment on such things during this ceremony. We offer only prayer and critical hope for the future. When my mom worried that not enough people would show up or there wouldn’t be enough food, I reminded her of this. We don’t worry about those things so as to not pass on those anxieties to the younger ones.

This ceremony is about bravery, and I was hoping my instinct to take on the butchering would pay off. This ceremony is also about showing yourself to the world for the first time. So I was hoping to emulate that in any way I could; to be an example, an uncle, no longer a child.

In college, I joined the Diné of UNM, a group devoted entirely to celebrating and exploring Diné culture. Every spring semester, we traveled to To’Hajiilee, New Mexico, a small town just west of Albuquerque—the closest piece of reservation we had—to learn how to butcher a sheep. We camped, told stories, and taught each other how to butcher from start to finish. The ones who knew how to butcher taught those who did not know, and we each went around sharing what we had been told, what we knew from family stories. No one was ever wrong in these circles. Food sovereignty. A group of kids experimenting with instinct, story, and a deep respect for land and nature.

Sheep represent so much more than food, so food sovereignty itself represents the inherent right of peoples to their own ways of living. “Sheep is life,” as the saying goes. Sheep offer nourishment, clothing, and tools. No part of the sheep is wasted. However, to get this harvest you must tend to the sheep, waking up early every day to ensure their survival. This shepherding gives way to a circle of care and attention that births a way of life. A way of life we have an inherent right to. This is food sovereignty.

I come from a lineage of people who had sophisticated approaches to nourishment, corn being the prime example of what Native science could engineer. But despite our long history of relationship with food, the government built a system of dependency, introducing families to commodity foods. This practice diminished the validity of Native science and agricultural engineering altogether. The Consumer Protection Act of 1973 established the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, which sought to increase the livelihood of Native people. As children, we tore through white boxes with black text that read “Corn Flakes Cereal,” pried open canned pineapple juice, fruit cocktail, and powdered eggs. For quick lunches, we would put “commodity cheese” on tortillas or bread. The cheese is a household treasure where I’m from. It’s a delicacy. But the flavors we savored in childhood became a detriment to our health. In my research into the program, I found many articles that explored the link between commodity food and obesity rates on reservations. Eating dinner from cans and boxes as kids often leads to eating dinner from cans and boxes as adults. I’ve called it comfort food.

At the only convenience store in Tsaile, Arizona, I saw a mother buying groceries. In her cart, she had the staples: Hamburger Helper, ground beef, Spam, potatoes, bread, cereal, chips, bologna, American cheese, and snacks like cookies and Ramen noodles for her kids. She also had The Holy Trinity: lard, Blue Bird flour, and baking soda. Filling your stomach on the reservation is a tale of processed foods. Humans need food, so we go out and buy food. There shouldn’t be any shame in that. But this system that creates food deserts and marginalizes communities can make you feel at fault for not finding nourishment, even though the structures in place limit access to quality foods.

Each memory folding into a story. And each ingredient of the food we enjoyed folding into even more stories, each food carrying a story of its own. Food sovereignty.

I traveled into Rock Point, Arizona, with my partner and his sister because she was training to run for Miss Navajo Nation. The pageant had created a new traditional foods competition, so my partner and his sister turned to the one person they knew who would be able to teach them: their grandmother. I was scared because their family is fluent in the Diné language and have a strong knowledge of ceremonial ways, and I felt like I didn’t know enough or even belong at all. I was a child again, watching and trying to learn. The teaching moved quickly and went on into the night. Their grandmother told a few stories then showed my partner’s sister how to make the dish—only once. From there, it was trial and error. She took charge and carefully moved through the motions. Her grandmother only offered small words and phrases of correction. They showed no hesitation. I think I was the only one feeling it because this environment felt foreign to me.

Looking back, I now realize that this kind of education is crucial to surviving and there is no room for hesitation. This experience might have spurred a kind of loose confidence in myself that drove me to take charge in the butchering. It also showed me a kind of pedagogy that exists in our communities. There are no grades in these moments, only stories and sometimes another pair of hands to guide your way. My partner tells me often that his upbringing shaped a way of interacting with the world. I felt it when I was there, watching them in utter wonder.

Their house had no electricity, so the light grew dimmer as we sat around the fire and ate the fruits of their labor, their offering. Soon, it was night, and we were still sitting outside in the pitch darkness with only a partial moon for light. No sound for miles. Just us and the cosmos. Each star a story. Each rock formation, another. Each memory folding into a story. And each ingredient of the food we enjoyed folding into even more stories, each food carrying a story of its own. Food sovereignty.

My partner’s sister ended up winning the title of Miss Navajo Nation, and we believe it’s in part due to the rare traditional dish she created and the story behind it. While serving in the role of Miss Navajo Nation, she kept the traditional foods category in the competition, and it continues to this day. Another Miss Navajo Nation titleholder even helped produce Cooking with Miss Navajo Nation, a bilingual cooking show where she demonstrated ways to make traditional foods. The first episode featured chiiłchin, or sumac berry mush, which is a storied dish, famous across all of Navajo.

During the latter part of the pandemic, my partner and I decided we would visit as much of the rez as possible. So we drove with some friends to Page, Arizona. Woven through the ridge lines, meadows, and open fields were the stories we told about our past, about times we did things or said things. We talked about our families. We grew hungry. In a small town, we pulled into a local flea market. An older woman, grandmother-age, was selling chiiłchin. We stopped and bought some to enjoy on the road. One of my friends had never eaten it before, and this opened up many stories about chiiłchin, and those stories unfolded into even more, carrying us to our destination. It was as if no time had gone by. In a flash, we were driving into Page.

Stories have a unique ability to collapse time. Food does, too. Stories move through time differently than we do. They can move between times, slow time, or even stop time. Food operates similarly carrying metaphors, images, and memories. Which is why so much of our culture involves gathering around a table for a nice sit-down dinner or hunching over a barstool on the roadside to devour street tacos. Each culture carries traditions around food. Native and Indigenous foods also carry certain traditions. They are able to navigate the past, present, and future.

Blue corn, for example—a staple dish for Navajo people—embodies the past, finds innovative representations in the present, and acts as a metaphor for a future where Native people can express sovereignty. In a trendy brewery in the Wells Park area of Albuquerque, New Mexico, called Bow & Arrow, I had an American Pilsner made with blue corn. Bow & Arrow is sharing with the world unique ways to use Native ingredients to create an experience. Each experience at the brewery is different, and the brews themselves change with the seasons, because the ingredients are versatile and can create stunning concoctions that represent an entirely new way to tell a story through food. This is an example of reclaiming the stories that exist within our foods and the power that can be felt when enjoying their flavors. It’s more than food, it’s a lifestyle.

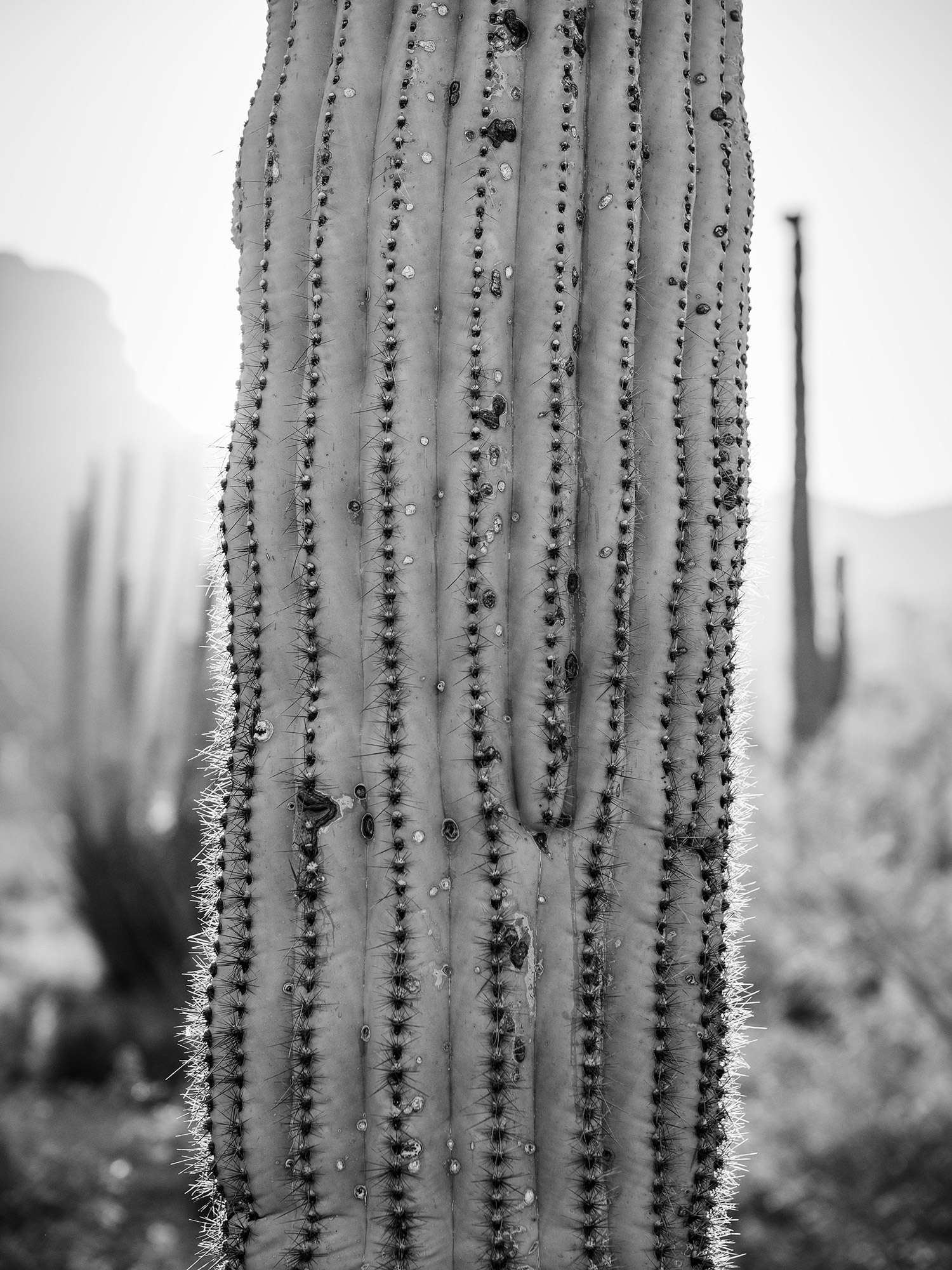

Diné farmers are also beginning to see the ways in which farming and food can help sustain a very sacred Diné way of life. Graham Biyáál started Biyáál Trading Post, which sells seeds, teas, and other materials needed to make traditional foods, like the Tąąniil & Blue Corn Pancake Kit and Gad Bit’eesh, juniper ash, which is needed to make blue corn mush. In my cabinet right now are blue corn seeds from Biyáál’s farm. I visited his farm and homestead after a series of storms had changed the landscape of the area in 2021. He texted me about the potential of getting stuck in the mud, but I was determined to get my hands on those seeds. I haven’t found time to plant them, but I am hoping to continue the story of these seeds, the seeds in my cabinet. Their legacy transcends families, borders, and timelines, each carrier committing to their survival; each adding their own stories to the collected voices already ingrained in the seeds themselves. The seeds are the start of a cycle: the tilling, the plowing, the planting, the watering, the tending, the harvesting, the preparing, the cooking, the nourishing, and the sharing. After harvesting the fruits of the labor, we digest that history and allow it to nourish our bodies. That is how food is supposed to operate, as part of story.

There is no way to explain this to my doctor at our check-ins. It’s not easy to talk about this history in such a short period of time. Through no fault of her own, my doctor sees me through numbers: this is high, that is normal, this is a little high, that is a little low. The mechanisms of my body are as complex as the universe it seems. Too much of one thing throws it off its axis. Each food makes its journey known through your body, and we exhibit that journey through our emotions, our energies, our physicality, our actions. My body is telling me that I need to take time away from my work and make time for myself and those stories.

But for myself and others like me, time is not an easy thing to come by. I can’t even imagine the families back home on Navajo, the way time is more fluid there and easily evaporates into nothing. Growing up, my mother commuted from Vanderwagen, New Mexico, to Window Rock, Arizona, across state lines for work. Both of my parents worked full time. It’s the same today, finding time is difficult. It’s almost as if “being healthy” is altogether unsustainable.

The answer to this predicament is easy: a return to our own agricultural histories. That return can be both literal and figurative. We can quite literally return to our own ancestral foods. However, figurative returning can mean allowing foods to travel through time, to be timeless, or rather to be timeful. They are artifacts that hold within them all the stories and traditions and generate more and more each time they are prepared. An artifact to hold with it all the stories and traditions that can generate more and more each time it is made.

The term “agricultural history” implies that history exists in the past tense. However, history is an active presence and can be a tool for futuritive imagination: for example, blue corn reimagined into contemporary dishes and Miss Navajo Nation teaching how to make blue corn mush. The past, present, and future exist simultaneously. There are movements toward a transformation in our relationships with food—more intentional relationships and less reactionary ones. I make small steps in that direction as well. However, it’s not as easy to determine how to disengage from the agricultural and consumerist practices that are draining resources from the earth. How do we stand against that machine?

I hope for more moments where I can lean into the sovereignty of food to reclaim a way of life stolen from me. I hope for a healthier way of living that’s sustainable and that addresses the needs of my own complex body and the world around me. I hope for language that can best articulate this complex history and these complex wishes for a future. I hope that I might help others move through their own health journeys, but not like social influencers who market health through lecturing and shaming rather than discussing. I hope to tell well-rounded stories, both with language and without. This hope is a radical one; both optimistic and critical. It is a revolutionary act.

In what I have learned from Diné ways of living, the morning time symbolizes this kind of ambition. Each morning is another opportunity for beauty, each sunrise a promise, each day a blessing. It’s never just another morning and another day. Still, pressures build, dams give way, and there’s another mild breakdown in the middle of a kitchen when the stew burns, dishes pile up, or food runs out. But in all that undoing, another day is about to break.

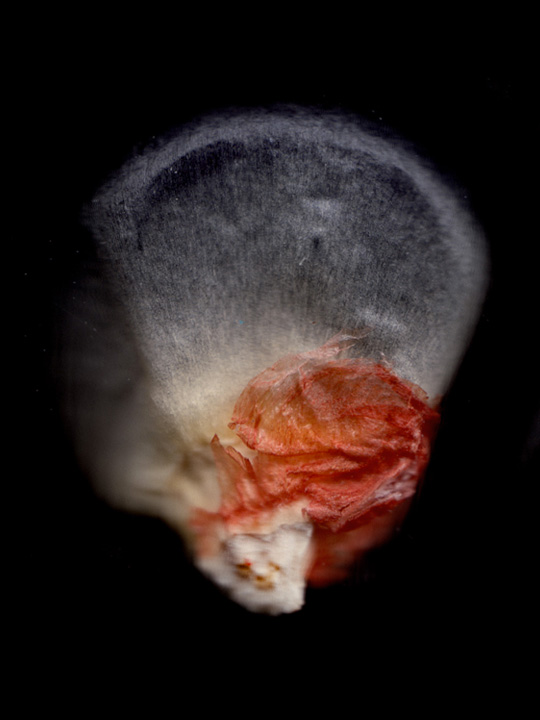

The butchering started like any other: the sheep faced east per protocol. My mom and uncle were telling me what I needed to do to properly cut into the neck. We don’t think of suffering at times like this, we think of nourishment; we don’t think of sacrifice, we think of offering. The sheep had been looked after for years. Each morning, someone ventured to the corral to let it out to graze. Each day, it was given food and water. Each spring, a new haircut. Generations of sheepdogs, one litter after another, had been trained to care for the sheep. Offerings were made, money passed, to sustain the land, the corral, and the health of the herd. My own family cared for a herd of sheep and goats so I know this well. My aunts made a slow walk to the corral every morning, just like their mother and her mother and her mother. My grandmother even tied me to a high chair once and dragged my mom to the corral to care for the herd.

Each sheep represents life. Each sheep represents living with nature. So I cut into the sheep’s neck with care and precision, despite my own worries, because we were gathering to celebrate life. One of the things I learned during our trips to To’Hajiilee was to let the knife guide you, because guiding the knife could lead to forcing the knife into the meat or bone. This could lead to even more mistakes. You should trust the knife and trust the instinct. The very first act, the severing, must be done in an exact spot to minimize suffering.

I hesitated and asked my mom for help. My older cousin, without hesitation, grabbed my hands and guided me toward the spot. “Like this,” she said. My younger cousin took over from there, again without hesitation. In that moment, I felt safe. I didn’t feel shame. I felt safe.

And from there, my mom and sisters got to skinning. Each one teaching the other, everyone learning, leaning into instinct, into generations of knowledge, coming together, just like when I was a kid, helping out, wide-eyed to it all. And for a moment, I was a child all over again. I listened and helped when I could. I kept thinking, if only I had listened when I was a child. If I had listened just a bit more, I might’ve been able to butcher two sheep that day. Maybe even three. My mom wouldn’t worry so much, and I would be able to carry for my family a tangible skill, unlike writing poetry, for example. As an uncle, I wanted to contribute in a way an uncle should. And in that moment I realized I had help and I should contribute in any way I can. My older cousins were there and they knew how to do it. And even more salvation was on the way.

From the corner of our eyes, we saw the glint of a windshield making its way down the road toward us. My mom had put a call out to my father’s side of the family, a lineage of strong women who come from strong women who come from even stronger women. Each one a vessel of laughter and lesson, open and tough love. They were coming to help.

We all shared our gratitude as they walked up, joking that someone had put into the wind that we were needing a pair of butchers. It was my aunt and a grandmother from my dad’s side of the family, one I hadn’t met before—because being Diné means having family you know nothing about until it’s time to gather for a ceremony and then you meet them and share a connection deeper than time. So much history entangled and detangled with a simple acknowledgment that we were connected through blood, through story, through commitment, through gatherings.

My aunt was getting older and my grandmother was older as well. They could not do the butchering on their own, so we all continued to help, and they taught us all over again. Guiding where we cut or how to follow protocols. Each lesson a story, each story a lesson. The butchering was never about the ending of a life for personal gain but a deep relationship between elements of nature. Hope is the thing with wool, after all.

The sheep was not as large as we thought. There wasn’t enough sheep fat to create achii’, or sheep fat wrapped with intestines and grilled, a dish that is considered a delicacy. It’s best enjoyed with naneeskadi or Navajo tortillas. My aunt wasn’t worried, however. She showed me a way to make a medley of intestines, sheep heart, and liver with onions. “This was your dad’s favorite when he was young,” she shared, as we enjoyed them over an open fire. And in that moment I was connected with my family in a way I had never been before, with their history, with their youth, their comfort foods, their upbringings. The power of it all held in my hands and devoured with some salt. So we sat around the fire some more and we made more food and told more stories. My parents and aunts and uncles unlocked new relatives and new connections. They shared wisdom that helped squash all the anxieties my mother was feeling. We stayed around the fire into the evening, and right before we started to clean, there was a moment of silence. A sigh of relief. One long exhale. The sound of worries let go, troubles melted down, and pressures unsealed. A family sitting around a fire telling stories and eating them, too. It was a great way to wind down from a butchering, which shouldn’t be called “butchering” at all, but gathering, sharing, opening. A way through. A way back. A way forward. Filled with memory and future. Best served right off the grill. A flavor of hope.

The next time I butcher I’ll have my own story to tell, my own memory to share, knowledge to offer. One more voice to add to the chorus on those nights when you’re out in the desert under the night sky, no sound for miles, just the moon and the ground beneath you, reminding you it’s all real. That and your full stomach. Generations heard through wind, the air, the stirring gleaming stars. All that knowledge, all that story, all that beauty.