Crystal Wilkinson is the author of The Birds of Opulence, winner of the 2016 Ernest J. Gaines Prize for Literary Excellence; Water Street; and Blackberries, Blackberries, nominated for the Orange Prize and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. She is a recipient of the Chaffin Award for Appalachian Literature and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her short stories, poems, and essays have appeared in the Oxford American and Southern Cultures, among others. She is an Associate Professor of English in the Creative Writing MFA Program at the University of Kentucky.

Joe Gough is an Illustrator living in New York City. He is a graduate of the Illustration as Visual Essay MFA at the School of Visual Arts. His clients include Bloomberg, The Believer, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Variety Magazine, and more.

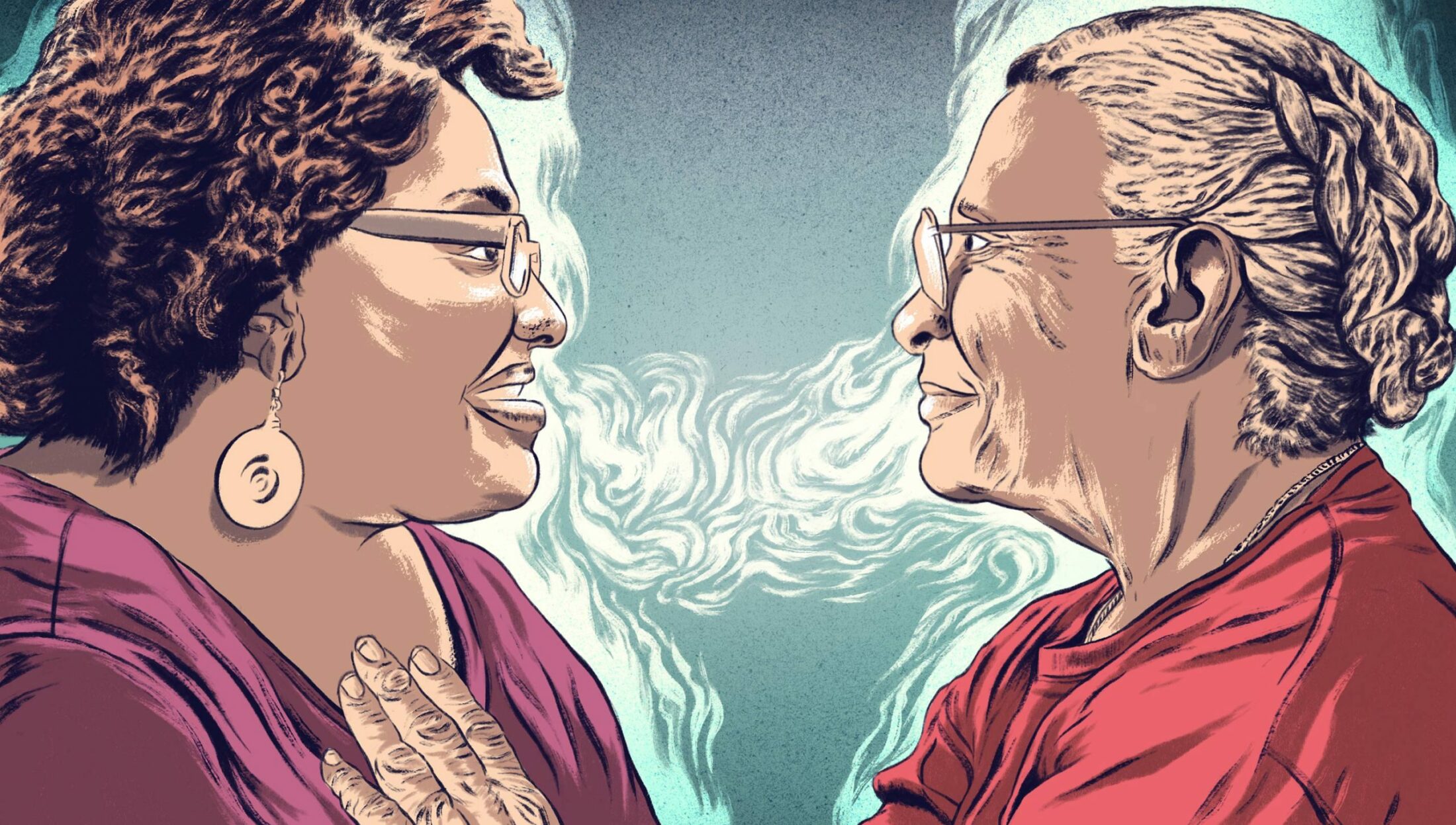

Crystal Wilkinson offers this contemplation on the intimacy of breathing and breath as she considers how we live, die, and love.

My mother is dying again. I sleep on the couch in the living room while my partner curls up, snoring in our new bed. Within reach are a water bottle, three remote controls, an amber bottle of alprazolam, a novel, laptop, and cell phone. My mother appears just as she did a week before she died. Her mouth pursed into a thimble, panting short, rapid breaths. The bedside monitor sounds. Nurses rush in. I stand in the middle of her hospital room. Helpless. And then I wake up relieved to be lying on the couch.

My mother died four years ago. A dream? A panic attack. This occurs so often it no longer matters what I call it. I reach for the remote control, push the channel button until something steals my attention, until my breath slows. I sip cold water. I almost never read. I almost never write. Sometimes I eat snacks. I almost always post something on social media. Sometimes I play videos. I almost always prefer videos of babies. Sometimes I go to the bathroom and stop by our bedroom to peek in on my partner. He is snoring. He is alive. Occasionally, I slip under the covers next to him, but I hate breaking his sleep. Sometimes I return to sleep an hour or two. Sometimes I cannot sleep for the rest of the night.

“Babe, you okay?” my partner says when he hears me stirring around in the dark.

I always answer, “Yes.”

Any other answer is too complicated.

“You good?” I say back.

He always answers, “Yes.”

Any other answer is too complicated.

We both say, “I love you.”

This is our routine before COVID-19.

Three months ago, one day before what would have been my mother’s eighty-first birthday, my partner returns home from a routine doctor’s visit with an unidentified lung ailment. The “little catch” in his chest was something to worry about, after all. After five minutes of walking, his pulse oximeter reading dips below eighty-six percent. I pray for a fluke, hope for a cure. Later we learn that his CT scan is clear of blood clots or masses, but his breath is puzzling, not normal.

“What are they going to do?” I ask.

“More tests,” he says.

I ask him how he feels about it. He does not say much.

We deflect.

More tests in our relationship, too.

At night we return to our separate spaces: I to combat my panic attacks, he to reflect alone. I find myself standing at the bedroom doorway in the middle of the night. I listen to his breathing.

During the day I grow quiet. He can tell I am worried.

“How you feel?” I ask before breakfast, during breakfast, and again after breakfast.

“How you feel?” he says, and exaggerates the word you. It sounds ridiculous. We laugh, but we still do not discuss this new thing looming.

I think about my mother.

I think about my partner.

Day.

Night.

Four years ago, I slept in a chair at the foot of my mother’s hospital bed for forty-five days. Every morning I helped her wash her face, put her dentures in. I combed her hair and twisted it into a knot on top of her head. I adjusted her glasses. She looked more vulnerable with her hair disheveled and her teeth out, like someone who was at the end of their life. I already knew of the disparities in health care for black people. I refused to let my mother’s life be expendable. I wanted to prove that my mother, even at age seventy-seven and in fragile health, was still a black woman deserving life.

I watched my mother go into cardiopulmonary arrest twice. Once in the hallway of her apartment building, while the EMTs were placing her on the stretcher. She had called me fifteen minutes earlier to say, “I’m not breathing right.” Again in the ICU, after they had taken her for an X-ray. Hypoxia. Short rapid breaths that yielded no air. She was put on a ventilator twice. The second time the doctor called in the family. A minister prayed with us, gave her last rites. When they extubated her, my mother’s breath leveled. She was breathing on her own. She opened her eyes, saw us all standing around her, and told us to sit down. “Take this baby,” she yelled at my daughter, who had placed our six-month-old granddaughter into the crook of my mother’s arm. We cut our eyes and smiled at each other at her terseness. “You all got some ice cream?” my mother said. That is who she was. We laughed. I smiled at the doctor in triumph. “We’ll see,” he said, and clasped his hands behind his back like some television version of himself, and left the room. But he was right; she died a few days later, despite our celebration. Her breath failed her one last time.

I would like to wake up smiling, pleasantly remembering my mother’s laugh. I would like to see her plait her long white hair. Watching her fingers wind through the strands has always been a sort of meditation for me. Maybe she could come back cooking potato soup or frying salmon croquettes. I’d love to see a vision of her sitting out in the sun. I have wonderful memories of my mother. I wish these joyous images would slip into my vision, but we don’t get to control our dreams.

Two months ago, my partner and I traveled to New York for the debut of his latest collection of poetry, our first trip since his lung troubles. The trip involved wheelchair assistance through three airports and canceling most plans to explore the city. It was stressful for him, for me, and his publisher, who spent a lot of time trying to navigate curbside drop-offs so my partner wouldn’t have far to walk. The event was held at a jazz club in Greenwich Village. There was a parking problem and steps, things we had never had to think about before. I, along with another Kentucky-born poet, opened for my partner. Against a red-lit background, my partner read, pausing to catch his breath in the middle of his performance. He was self-deprecating, funny, and brilliant on stage. We hugged friends new and old. On our last day in New York, my partner’s publisher dropped us off at the Schomburg Center, but we only made it to the gift shop. We successfully negotiated LaGuardia again and made our way home to Kentucky. The same day we left, a Manhattan healthcare worker who had just returned from Iran, became the city’s first case of COVID-19. And within a few days the pandemic had reshaped all our lives, taken all our breaths away.

Between my mother’s nightly appearances, I search the internet, reading about what the sickness does to the body. One article from Science magazine says “the lungs are ground zero.” I tell my partner and my children that I am glad my mother is not here for this. “She’d be scared,” I say, but the truth is I am the one who is terrified. I want to scream at my partner, “I can’t watch someone else I love smother to death.” But I do not say that. Silence takes up all the empty spaces in our house. “We are black, we are fat, and we are old,” I tell him. “We have a target on our backs.” We laugh, but we both know it is no laughing matter.

Our throats are scratchy since we’ve returned from our trip. At night, on the couch in the darkness, I breathe in and breathe out slowly. One night, I cannot inhale a full deep breath without pain in my chest. It burns. Panic attack or sickness? I whisper to myself. But I guess they are both ways of being sick. I take one half of the tiny anxiety pill prescribed by my doctor and close my eyes. My therapist told me once to use my writer’s imagination to get through moments of unease. I try to think: calm stream, flower petals drifting, breeze on my face. But instead, hypoxia, droplets, alveoli, pneumonia, underlying conditions, and death seep in. Sometimes I get up in the middle of the night to wash my hands. I take vitamin C. I drink hot tea.

By mid-March, the first cases of coronavirus infection have spiked in Kentucky, not in Lexington, where I live, but in the bucolic town of Cynthiana. Officials at the university where I teach decide we will move to online instruction two weeks after spring break as a precaution. I remind my students to wash their hands. I’m normally a professor who insists on hard copies, but say send your assignments via email only. On campus, I have taken to reaching up high on the large metal and glass doors in the building where I work. I stand on tiptoe and push open the door away from sight level where I see the most fingerprints. I spray disinfectant when students and fellow faculty members leave my office. I don’t attend face-to-face meetings. Black and brown faces crowd my social media timelines. My heart skips a beat every time I see another story of another death. I watch the colorful charts and graphs mapping the growing number of cases across the country. The number of deaths climb and the orange line that indicates trajectory is growing fat and long across my screen. My obsession with China and Italy is replaced by my obsession with Seattle, Detroit, Missouri, and New York, and, of course, Kentucky.

During the last days of class, before spring break, I give handwashing lessons to my colleagues in our tiny bathroom on the twelfth floor. “No, no,” I say. “This is how we are supposed to do it now.” I tell them to get their thumbs and do not forget the tips of their fingers. I have one last in-person meeting with a graduate student. She is concerned about flying back to her partner in San Francisco. I turn from teacher to mother. “Gloves,” I say. “Use disinfectant on the plane. Become Naomi Campbell,” I say. “Don’t be embarrassed. This is your life.” My voice cracks so I stop talking. She takes a social distancing selfie. I am wearing a yellow dress. We smile wide and make sad faces. “See you soon,” I say. I disinfect my office and cry when she leaves.

When I come home, a large concentrated oxygen machine looms in the corner of our bedroom, and six smaller white and green metal portable tanks stand like sentinels in the middle of the floor. My partner says that he has been instructed to wear the concentrated oxygen at night while he sleeps. The portables are to wear “upon exertion.” The large machine makes a whooshing noise when he turns it on to demonstrate. There is enough oxygen hose to reach all over the house and out into the yard. “You’ll never come to bed now,” my partner says. “I will,” I say, but at least at this moment it feels like a lie.

Twenty years ago, these same items were crammed into my mother’s small apartment by a pulmonary technician. My mother nested the green and white tanks horizontally under her bed. The metallic clank set my teeth on edge when she used the vacuum and the tanks bumped against one another. Back then, Mama smoked three packs of Kool Lights 100s a day. I thought there would be an explosion. Her walls were yellow with smoke and she coughed until she strangled. Even after my mother quit cold turkey when she was diagnosed with bronchitis, the cough remained. We thought she’d be on oxygen temporarily. She was never without it.

The pulmonologist says my partner needs two liters of air while he sleeps.

I order groceries from the delivery app.

I wash the groceries in bleach and water.

I sneeze.

I wave at my adult children from the driveway.

I bake bread.

I miss my mother.

My partner sneezes.

The television drones on: racial disparities, underlying health conditions, morbidities.

Two of my friends in New York who attended our event have the sickness.

My university says that we will be closed for the remainder of the semester.

I make homemade enchiladas.

I teach my classes via Zoom.

Zoom office hours.

Zoom group presentations.

I check on my friends.

Zoom faculty meetings.

I miss my mother.

I miss walking in the arboretum.

Zoom happy hours.

I move my laptop from room to room and finally onto the front porch trying to get the right light to get the right feel.

Nothing I do makes the private feel public.

The squirrels are wild in the attic.

My students take their finals online.

I record critiques for their stories.

My partner writes poems.

I Zoom with my beloved grad student in San Francisco.

I Zoom with my beloved grad student on the other side of town.

My partner draws with charcoal and pencil.

I dream of my mother.

I find her death certificate.

Cause of death: COPD, renal failure, respiratory failure.

Failure.

My best friend’s sister is dying of brain cancer. “Thank you for making me laugh,” she says when I call.

I watch everyone in the neighborhood walk their dogs.

I order books.

I bake bread.

I read.

I write.

I watch television twenty-four hours a day.

I sleep on the couch to the whir of two liters of oxygen coming from our bedroom. I cannot hear my partner snoring anymore above the loud whirring of the machine. Sometimes when the tubing gets kinked a loud beeping alarm screams in the middle of the night.

I take a full dose of the anxiety medication. It gives me a headache and does not stop the dreams completely. I still wake up with my heart racing, but with the drugs I do not always remember what has happened. I wake up disorientated and too groggy most nights to pay attention to what I’ve dreamed. When I sleep until dawn, I force myself up quickly and stand in the doorway of the bedroom. I wait. There it is—the snoring in off-rhythm with the whooshing sounds of the machine.

I clean, wipe the doorknobs, the sink, the kitchen counters several times a day.

We are sheltering in place.

We do not leave the house.

The one day we do leave, we go to a neighboring town to buy fresh bread from our friend’s bakery. We pay online and after the baker comes to the car and throws the bag into the back seat behind where my partner sits, I back the car into a stone fence and scrape a hand-sized gray mark into the blue paint.

We have bought bread, but I make more bread anyway.

I am startled by the mailman when we are suddenly on the porch together.

We freeze for a few minutes, then give a knowing nod in each other’s direction.

I order groceries.

Bleach. Rinse. Repeat.

The officials finally confirm what I can see with my own eyes. More brown and black people are dying.

Underlying conditions, they say.

My friends with the sickness (one black, one white) are improving.

Another friend’s grandmother dies.

Another friend’s teacher dies.

Another friend’s aunt dies.

A local bus driver dies.

Famed musicians die.

A noted literary scholar dies.

My friend’s sister dies.

A face appears in my dream. Maybe it is my mother. Maybe it is my friend’s sister. But a woman’s face appears cloaked in the shadows, and she says, “Tell her you love her.” So, I text my friend and tell her I love her. I am convinced that this message is for my friend who has lost her sister, but maybe I’m wrong; maybe this message is intended for my mother.

I love you, Mama, I whisper.

Later, when I call my friend, she says, “I’m lost without my sister. I wish I could call her to tell her this.”

My phone dies.

My partner says, “They say the average adult should breathe twelve to twenty breaths per minute.”

I nod my head.

“Anything below twelve means you’re in trouble,” he says.

“How many do you have?” I say.

“Twelve.”

When I was six, I drowned. I have described the close call this way my entire life. I can still hear my grandmother say, “No, Honey, you almost drowned.” I slipped in the creek. I sputtered for air until my grandmother waded in to save me. My mother stood on the shore and watched, waited.

I remember not being able to catch my breath. I still do not like water in my face. I wash my face before or after I enter the shower. I do not swim. A boyfriend once pried my hands off a ladder on a snorkeling boat sending me crashing into the sea while we were vacationing in the Bahamas. It was a joke, he said. All in good fun, he said. The water only came up to our knees when we were standing, but I was too traumatized to look at the fish. I broke up with him once we returned to Kentucky.

When I tell my partner the story, he says, “You’ve told me this before.”

That was before the sickness, I whisper to myself.

A whisper is a sort of breath. A whisper is a secret. In my family we hold secrets. We hold our breath.

When I asked my mother about my drowning, she said, “I heard that the Indians train their babies to swim by throwing them in the water.”

I wish I had asked her more questions.

I hear the click of the concentrated oxygen machine as it whirs to a stop. My partner staggers out of the bedroom and kisses me good morning.

“Good morning,” I say.

We say, “I love you.”

We watch yesterday’s news about the sickness.

“Toast?” I say.

He says, “Yes.”

“Coffee?” he asks.

At the kitchen counter, he shakes the beans into the grinder before I say, “Yes.”

He grinds the beans, pours the hot water into the pot, then presses the plunger of the French press.

I say nothing.

My partner is talking about an article on his phone.

I can hear the birds chirping outside, but I can’t hear what my partner is saying. I am remembering my mother. I am remembering the long, tight hugs of my children, laughter echoing in bars and restaurants. I am remembering a celebratory night in a bar, backlit in red. I am remembering conversations with my students and long, slow walks at a nature sanctuary. I am remembering the granddaughter who was in my mother’s arms, now four, wearing a yellow blanket like a Supergirl cape on our front porch. I am remembering being curled like a question mark in the arms of my lover, the silence punctuated by his sweet breath in my ear.

None of us should be remembered for the way we die but how we have lived instead.

I look up at him and smile.