Boyce Upholt is a freelance writer. He is the recipient of the 2019 Award for Investigative Journalism from the James Beard Foundation and was named a 2016 “Writer of the Year” by the International Regional Magazine Association. His work has appeared in Mother Jones, The New Republic, The Atlantic, TIME, The Oxford American, and The Believer, and has been included as a “notable” selection in the Best American Science & Nature Writing series. He is currently working on a book about the Mississippi River.

Bear Guerra is a photographer whose work explores the human impact of globalization, development, and social and environmental justice issues, often in communities typically underrepresented in the media. His work has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Le Monde, BBC, and NPR, and has been exhibited widely. He was a finalist for a National Magazine Award in Photojournalism. Bear and his wife, Ruxandra Guidi, work together under the name Fonografia Collective to produce local and international print, radio, and multimedia stories about human rights and social justice. Bear is also a board member and producer with the award-winning nonprofit journalism collaborative, Homelands Productions, and is the visuals editor at High Country News.

The O’odham peoples of the Sonoran Desert have long revered the saguaro cactus as a being with personhood—a belief that is congruous with the recent rights-of-nature movement. As legal protections for the cactus come up against the push to build a wall through Organ Pipe Cactus National Park, Boyce Upholt travels to the US-Mexico border, where a coalition of Indigenous voices are speaking on behalf of the rooted beings of the desert.

“The saguaro can be understood as free of the earth, like human beings…”

—Jane H. Hill and Ofelia Zepeda1

In 1982, a man named David Grundman shot a twenty-seven-foot-tall saguaro cactus. His reason remains unarticulated in the Arizona Republic article that recounts the crime, but we know that Grundman managed to get off two blasts from his sixteen-gauge shotgun before the cactus enacted its revenge: twenty-three feet of its central column—thousands of pounds of cactus flesh—fell atop his body. According to witnesses, he had only gotten halfway through the word “timber!” Grundman was dead before authorities arrived on the scene, though he lives on now as the subject of a sardonic country ballad: “Saguaro / A menace to the west,” as the chorus goes.

Shooting is only one of the crimes perpetrated against this species, which can stand as high as fifty feet and weigh up to two tons. The saguaro is such a popular yard ornament that a good specimen can fetch a hundred dollars per foot on the black market. Theft is common enough that the National Park Service has installed microchips in a thousand cacti within the forests it manages outside of Tucson, Arizona. All but invisible, the microchips can be scanned to reveal if a cactus for sale in a plant shop has been taken from federal lands.

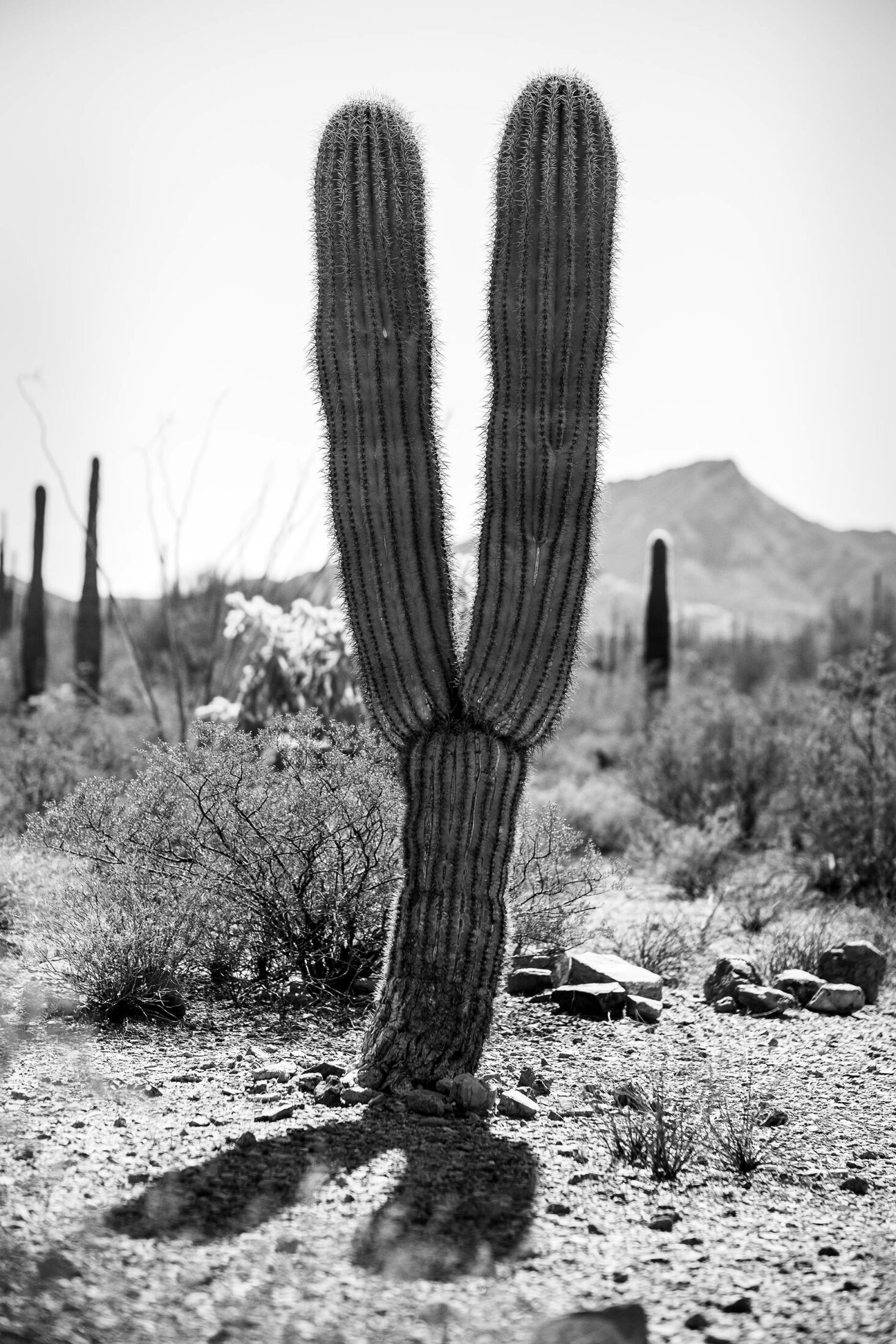

All saguaro in Arizona are protected; state law requires a permit before anyone can remove a cactus from the ground. This is, after all, the iconic symbol of the American desert—bent-armed, bright green, familiar from Sunday morning cartoons, and also from Arizona’s license plates, its scenic-highway road signs, plus countless postcards and neon saloon signs. Pottery Barn even sells a plastic saguaro for those who are “dreaming of the desert” but don’t want the hassle of maintaining a plant that might grow taller than their home.

The map of the saguaro’s range—which spans the width of Arizona and plunges south five hundred miles into Mexico—doubles as a rough delineation of the Sonoran Desert. The saguaro has been “a dominant presence” for millions of years in this region, in the words of the National Park Service. The dominant human presence, meanwhile, has been the O’odham—the People—who have wandered and hunted and farmed in this harsh landscape since, in their formulation, time immemorial. “The saguaro has always been a life-saving part of our culture,” Lorraine Eiler, a Hia-Ced O’odham woman and former member of the Tohono O’odham council, recently told me. It provides its fruit for sustenance; its ribs serve as material for constructing tools and houses. The cactus even teaches patience, Eiler noted, since to harvest its fruit is to commit to hard days working under a searing desert sun.

In 1853, in an effort to acquire the terrain most suitable for laying out a railroad, the United States purchased thirty thousand square miles of land from Mexico for $10 million. Thus, at least on paper, an invisible line severed the Sonoran Desert. Over the subsequent centuries, the line has hardened into an increasingly impervious barrier, one that splits O’odham families. Eiler told me that there is an ancient rite of passage in which young men run from their homes in the desert to the Sea of Cortez to collect salt. Today, this can be accomplished only by relay: one set of runners cross the desert in Arizona, stopping at a thirty-foot-tall wall of steel and concrete, where a second set of Mexican runners step in. To build the latest iteration of this barrier—the “big beautiful wall” that Donald Trump promised during his 2016 presidential campaign—contractors set explosives in desert soils where bodies were buried centuries ago. One Tohono O’odham politician has called this a “crime against humanity,” comparable to bombing Arlington Cemetery.

In early October 2019, many news outlets shared a cell phone video depicting the latest desecration: a bulldozer shoved aside a fallen saguaro at the border, on protected public land. The resulting outrage prompted the US Border Patrol to release a statement acknowledging that they were transplanting most cacti and using the bulldozers on specimens deemed unable to survive. Soon afterwards, residents reported that federal contractors were attempting to sell cacti at a market in Ajo, Arizona, a small town a few dozen miles north of the border. This was no small offense, since, as the Tohono O’odham have long understood—and the nation’s legislative council officially affirmed last year—saguaro cacti are people.

If the presence of the saguaro cactus provides an outline of the Sonoran Desert, the gradations of rainfall provide a chart of its internal topography. On the desert’s eastern edge, in the shadow of the tallest mountains, as much as a foot can accumulate in a typical year. With each mile you travel west, the landscape withers into ever-more-severe dryness, until by Yuma, Arizona, you can expect less than three and a half inches of precipitation. Though, then again, in 1909 more than four inches poured down on the city in a single day, the product of particularly fierce monsoon thunderstorms. Each summer, such storms rip in from the south, flashing floods, scoring the landscape into arroyos. The desert can appear monotonous to an outsider, relentless in its sameness, but this is a place that can change in a matter of hours.

Long before the concept of the modern nation-state arrived in the Americas, various O’odham carved out lifeways here. To the east, the Akimel O’odham, or River People, built ditches and dams, diverting the Gila and other rivers into enough acreage to allow a life in permanent villages. On the sere western rim of the desert, the Hia-Ced O’odham—the Sand People—survived as nomads, hunting jackrabbits and mule deer, pulling oysters and clams from the low-tide sea. They visited a natural spring now known as Quitobaquito, which still serves as a refuge and stopover during the annual pilgrimage to the Sea of Cortez. By the modern era, O’odham were permanently settled near a dam at the spring, which still sustains a small oasis amid the desert. It’s considered a particularly sacred place.

The Tohono O’odham, the Desert People, lived between the rivers and the coast, in the valleys tucked between the sacred Baboquivari Mountains and the Growlers to the west. Across this strip of land, there are no dependable streams, though those who know the landscape have always been able to find their way to a watering hole. The trees—mesquite and ironwood and palo verde—are stunted; in order to avoid being eaten, much of the flora protect their stems with spines and their leaves with foul-tasting and often poisonous oils. The Tohono O’odham spent the winters hunting, living in villages in the mountain foothills where water was easier to find. In summer, families moved down into the plains so they could farm the land that was rinsed into life by the surging waters of the monsoon floods. But before farming could begin, families gathered in temporary camps to harvest saguaro fruit, or bahidaj in O’odham. The harvest, which continues today, typically takes place in June or July, during Hashañi Mashad, or saguaro month, which in the O’odham calendar marks the start of the new year.

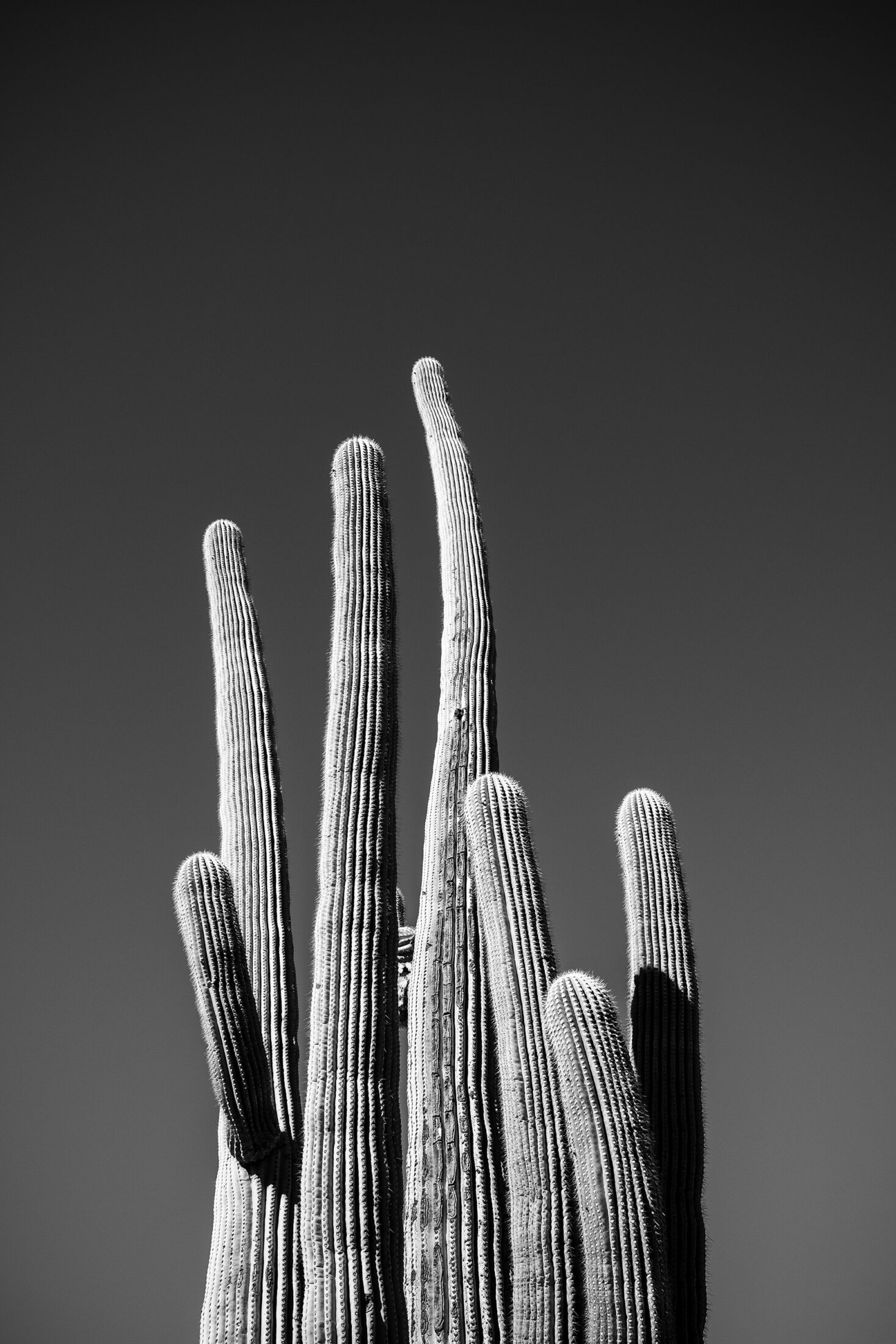

It’s a season of searing heat, with temperatures often topping a hundred degrees, though it’s also a moment of flourishing. As the heat spreads across the desert, the saguaro bursts into broad white flowers at the tips of its arms. Over several weeks, new flowers emerge in the evenings, and by the next afternoon each flower will fold shut, its short life already complete. Slowly, the closed pods blush into a pinkish-red fruit, ready for harvest. The gatherers depart from camp as the sun lifts above the horizon, carrying baskets and long poles made from a saguaro rib—the kuipad, as the tool is known—which they use to knock the fruit free. The red pulp of the first fruit to fall is used to paint the shape of a cross atop each participant’s heart, indicating the four directions; an empty pod placed at the foot of the cactus offers a message of thanksgiving and a request for rain.

“It’s very, very hard work,” Lorraine Eiler told me. “It’s hard work. Not only just to walk out there carrying, you know, sticks and buckets and what have you—and then, once you fill up your bucket, bringing them back—but also it gets really hot. But it also can be so much fun. It can be so much fun.” I could hear the smile in her voice, as she recalled the fruits falling, splattering, staining clothing with sweet syrup, a kind of messiness that can’t help but bring out an inner child.

I had hoped to visit Arizona during the harvest, but the coronavirus made travel arrangements difficult. So instead, I arrived in October—Wi’ihanig Mashad, in O’odham, the Month of Persisting, a name that references the way that, if all goes well, some of the planted crops will have managed to hold on despite long weeks of drought. This is supposed to be the onset of a milder season of weather, but the midday sun was still penetrating. Eiler and I chatted beneath the shade of a ramada at the elementary school she had attended in Ajo, Arizona, now converted into a motel and conference center. Ajo arose as a company town, founded by a mining concern, tucked into a mountain range where the O’odham traditionally harvested pigments used as red paint. The copper mine closed in the 1980s, but the pit is still visible today from an overlook: more than a thousand feet deep, it’s ringed by terraces that resemble, with some irony, the layers of skin encircling a wound in the process of healing. Most of the surrounding landscape is federally owned, by the National Park Service or the Bureau of Land Management, and the town serves as a jumping-off point for trips into the wilderness. After our interview, Eiler was booked to speak with a group of hikers who had joined a package trip organized by the outdoor retailer REI. The hikers, I learned, were spending the morning in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, walking in the shadow of the wall, through what was once the territory of the Hia-Ced O’odham.

You will sometimes read that the Sand People are extinct now, but they are not, as Eiler herself demonstrates. They are simply not recognized by the federal government as a distinct tribal entity. In the 1980s, that oversight drew Eiler, who was working as a nurse, into political advocacy; she worked to ensure that Hia-Ced O’odham were allowed to enroll as members in the Tohono O’odham Nation. Eventually she served on the nation’s legislative council. When we met, I was struck by her warmth, though there was something mischievous, too, about her easy laughter. As I turned on my digital recorder and began to launch into questions, she cut me off. “Let’s concentrate on you first,” she said, and proceeded to wring out some basic biographical details—establishing that this would not just be an interview, but a conversation.

It turns out I’m not the only one to have received such treatment. Once, she told me, a border patrol agent approached her during her bahidaj harvest, yelling, demanding to know what she was doing. She invited him to come see, and they struck up a conversation. He was from Texas and had been assigned to work the Arizona border for six weeks. Eiler wondered if anyone had told him about this desert. “No,” he replied. So she explained the harvest and demonstrated the practice. “Next thing I know, he’s pulling them down, and eating them,” she told me. He spent an hour with her, catching the sweet, wet fruit that rained from the green towers.

“The saguaro has always been a life-saving part of our culture.”

When the US and Mexican governments met in the 1850s to establish their new physical boundaries, no one consulted the O’odham. Villages’ calendars, marked on saguaro ribs and ironwood sticks, indicate the contemporary events that mattered to this society: there were battles against the Apache; there were trespassers, recorded in increasing numbers. There is no note on the sticks about political meetings or territorial change. The border may look simple on the map, clean and indisputable, but it does not match the shape of the Tohono O’odham world.

Even from the perspective of US law, this border is riddled with contradictions. The contract that laid out the terms of the land transfer has become known in the United States as the Gadsden Purchase. It included a provision that guaranteed property rights to any Mexican citizen who decided to stay on their land. The O’odham were considered citizens by Mexico, but, as “Indians,” they could not qualify for citizenship in the country that now claimed this land. What to do with that contradiction? In this case, the O’odham homelands were transferred into the public domain. The Tohono O’odham Nation uses ancestry as the basis for enrollment, regardless of their country of citizenship. This creates another kind of blurriness. The Tohono O’odham Nation is now formally recognized by the US government, so enrolled members, including Mexican O’odham citizens, are entitled to certain federal benefits like education and healthcare. Things get even more complex when you bring in the Hia-Ced O’odham, who were not consulted when the Tohono O’odham Nation negotiated its border with the United States. It’s a controversy that still colors tribal politics. Some Hia-Ced O’odham are seeking recognition as a separate tribal entity.

At the time of the Gadsden Purchase, the border was marked by metal obelisks, one every few miles. During the Great Depression, a Tohono O’odham man working on behalf of the federal government strung a four-foot-high barbed wire fence along the line. This fence was intended to stop free-ranging cattle from carrying diseases north. The O’odham were free to pass: they could detach a bit of fencing, walk through, then restring the wires. In the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, there were calls to completely fence this border. By 2010, the barbed wire had been replaced with “Normandy barriers,” X-shaped steel barricades intended to stop trucks from barreling through, named for their resemblance to the defenses used during beach invasions in World War II.

In 2019, the tribal council voted unanimously to allow the US Border Patrol to install towers equipped with radar and night-vision technology that can track people and vehicles within a seven-mile radius. The technology was manufactured by an Israeli firm and advertised as “field-proven,” given its success on the Palestine-Israel border. Some residents opposed the towers, but tribal officials hoped their installation would reduce the presence of actual officers ripping across the desert in trucks and SUVs, and perhaps forestall the construction of a wall across the reservation’s border. “We’re only as sovereign as the federal government will allow us to be,” then-vice chairman Verlon Jose told The Los Angeles Times after the vote, explaining what looked to many like a deal with a devil.

So far, at least, the wall has not reached the reservation, where the border is still marked by the old Normandy-style vehicle barriers. But in 2019, contractors started erecting a new segment of the wall just west of the reservation, along the southern edge of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, through the homelands of the Hia-Ced O’odham. The wall stands thirty feet tall; its steel beams are six inches thick, with four-inch gaps between. Already, just a few years after their installation, they are stained with rust. There is a roadway of packed dirt along the wall, which is lined with streetlights. When I visited, border patrol trucks roared past every half hour or so, kicking up thick clouds of dust. It felt to me as if the Hollywood set for some sci-fi film noir—a dingy, dystopian back alley—had been stretched for dozens of miles along the border.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service has noted that the wall through Organ Pipe could impact twenty-three endangered and at-risk species. It will alter the trajectory of future genomes, as populations that once interbred have been sliced apart by the wall. The National Park Service found at least twenty-two archaeological sites that were likely to be impacted by the construction. As the work commenced, the Border Service pumped more than eighty thousand gallons from the local aquifer each day to mix cement. The drop in water at Quitobaquito Springs was apparent to any visitor.

Throughout the construction process, officials made some efforts to save the saguaro in the path of the wall. Along the border today, the transplanted specimens stand a few feet beyond the cleared roadway, marked by small wooden posts. They often stand in perfect rows, like tiny, lonely gardens tucked against the long slashing line of steel bars. Scientists predict that over the next decade many of these cacti will wither and die.

The National Park Service indicates that, in total, more than two thousand cacti of various species were relocated. The agency kept no count of how many saguaro could not be saved. Eiler, whose grandfather grew up at Quitobaquito, helped organize a gathering at the spring to assert its sacredness and observe the damage. Fallen saguaro littered the ground. “They just bulldozed all the way through,” she told me, in a voice so matter-of-fact that I had to ask what emotion she felt. “It’s like they just completely overran your home, your beliefs, things that matter to you as a person, as a family, as generations of family.”

Biologically, the saguaro can’t claim any particular superlative: this is not the world’s tallest cactus, nor the largest, nor the longest lived. It’s simply beloved. Its rise in the American consciousness was driven in part by the same railroad that prompted the Gadsden Purchase. Trains brought the saguaro to the world—the species became a hit in many planned gardens—and brought the world to the saguaro. William Temple Hornaday, the director of what later became the Bronx Zoo, visited the region in 1907 and praised what he saw as a perfect stopover for railroad tourists. Hornaday particularly extolled the saguaro, which, besides its service as a nesting place for woodpeckers, seemed to be there only “to entertain and cheer the desert traveler.”

In the decades that followed, this did seem to become the species’ major role in American culture. By the 1950s, advertisers were clipping the barbs off cacti, dressing models in bathing suits and high-fashion attire, then draping the women atop cactus arms for portraits used to sell the region to tourists. It had become the icon we know today, the symbol of desert Americana.

Climate change poses some threats to this cactus, and not just because of rising temperatures. Worse is the fact that the desert may also freeze more often in coming years, which could kill off young saguaros at the northern edges of the species’ range. Ben Wilder, the director of the University of Arizona’s Tumamoc Desert Laboratory, told me he is most worried about the recent increase in wildfires, which can all but wipe out infant saguaros. Invasive buffelgrass thrives in the cleared landscape, outcompeting any new cacti. Wilder, though, says he’s optimistic for the cactus, which is already adapted to an environment of harsh extremes. “That’s exactly what’s happening with climate change: the extremes are getting more extreme,” he said. “I really believe [the saguaros] have a lot of secrets to tell us in terms of how to adapt to the changing climate.” You might consider this one more service that the saguaro could provide us, after already supplying its fruit and ribs and shade.

The saguaro was given its scientific name—Carnegiea gigantea—in the first years of the twentieth century, by scientists in Tucson hoping to flatter the wealthy philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. They wanted to establish a laboratory to study how life adapts to aridity—and they needed his money. Carnegie was revolted by the pandering, apparently, though he did decide to endow the Desert Laboratory, which in 1903 arose atop a sacred hill that the Tohono O’odham called Cemamagi Du’ag, or Horned Lizard Mountain, known in English as Tumamoc Hill. Soon afterwards, the hill was fenced to keep out cattle, which Wilder told me was the first experiment in restoration ecology conducted by Western scientists. “There’s a point of pride, right?—this victory,” he said. “But at the same time, fencing this property is the direct exclusion of all peoples. So that is just such a paradox.” Today, the road up the hill to the laboratory has been opened as a popular walking trail, a way for the community to connect with this ecosystem. Wilder hopes that during his tenure, some of the relationship between the laboratory and the Tohono O’odham might be subject to its own sort of restoration.

Wilder noted that much of the scientific knowledge of saguaros was drawn from these slopes, where the lives of the cacti have been tracked for more than a century. That’s a long time in human terms, but little more than half of a saguaro lifespan. “So while we think we really know these plants, we don’t,” he said. Before the laboratory was established, the O’odham played a role in the species’ population dynamics, eating and spreading saguaro seeds. Then the fence went up, and the people were kept out. The study, in a sense, was flawed from its beginning. “This has been a cultural landscape for thousands of years,” Wilder said. “The actual understanding of saguaro by the Tohono O’odham and their ancestors—it just far, far, far eclipses the understanding we have now.”

In US culture, the desert is often a symbol of death and lack: the fate we’re all spiraling towards in the grimmest tales of climate-change apocalypse. “When people say ‘desert,’ they think, ‘Oh my god, barren skulls’—and nothing else,” Eiler said. In truth, the Sonoran Desert is a lush place. The landscape around Ajo evokes the bed of a drained ocean, where somehow the seaweed had not just survived but grown into epic proportions. The cacti explode in wild profusion: organ pipe reach upward in dense clustered bouquets; cholla split apart into fractal branches. The stunted palo verde trees, with their smooth green wood, look like sea fronds, or perhaps monstrously overgrown dill.

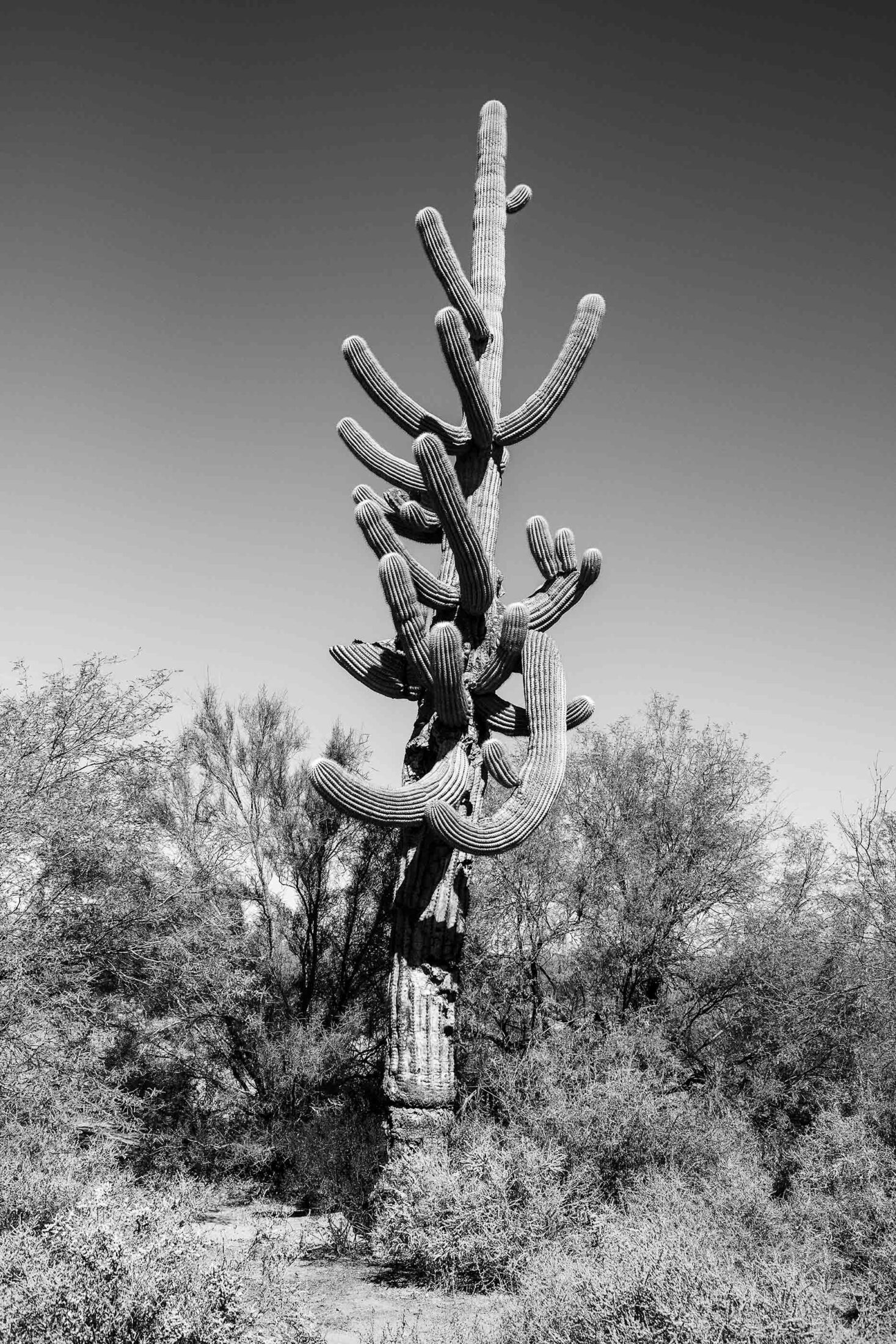

The saguaro—or Ha:sañ, in O’odham—towers over everything. Upon approach, each cactus reveals a distinct personality. Some are simple columns, limbless; others seem to explode into an overabundance of arms. Small imperfections tell the story of each cactus’s years upon this ground: black scars appear after a bad freeze; drooping arms signal some past period of heat stress. Cinches around a column—as if a belt has been overtightened—mark a drought. Some cacti are simply skeletons, the flesh gone, revealing the ribs beneath. These woody structures allow the living cactus to expand when rain delivers water, and can be harvested after a saguaro’s death. Most saguaro harvest camps include a ramada, often built from mesquite poles and topped with a roof of saguaro ribs.

“The actual understanding of saguaro by the Tohono O’odham and their ancestors—it just far, far, far eclipses the understanding we have now.”

Here in camp, the saguaro fruit is converted to its many uses. Seeds are pressed into oil or ground into flour or saved to be fed to chickens. The pulp is boiled over a campfire, strained and separated, boiled again: turned into a thick, sweet syrup, which in turn can be fermented into a wine—nawait—that is consumed in a sacred (and private) ceremony. The ceremony enacts an important O’odham story, in which Raven drank too much wine and afterwards vomited out the clouds. Similarly, the nawait ceremony is intended to conjure the monsoons that blast across the Sonoran Desert each summer—which provide the sole source of irrigation for traditional Tohono O’odham farming.

In ak-chin farming, as the technique is known, fields of beans and squash and corn are laid in the path of the seasonal arroyos. (Ak-chin, in one translation, means “mouth of the wash.”) Brothers Terrol and Noland Johnson manage one of the last large ak-chin farms, which sits on family land outside the village of Cowlic, Arizona. When I visited, Noland piloted an old Massey-Ferguson tractor through the tangled branches of tepary beans, which, without his guidance, I might have mistaken for tumbleweeds not yet torn free from the earth. Beyond the fields, there seemed to be nothing but withered yellow grasses and the occasional desert shrub, until off in the distance red mountains rose to break the horizon. Not a saguaro in sight. But its presence was essential, as Johnson noted: saguaro wine is how the O’odham call the rain. Ak-chin is a canny strategy, part of a seasonal rotation of food sources that allowed the Tohono O’odham and their ancestors to persist in this landscape for thousands of years. In contrast, since the Gadsden Purchase some places in the Sonoran Desert have seen the water table fall hundreds of feet and summertime temperatures increase by 4°F.

The importance of the saguaro is reflected in the O’odham language. Some speakers use a word for “armless saguaros” that, as the Tohono O’odham linguist and poet Ofelia Zepeda has noted, “is transparently related” to the word for “mothers.” The stories of the cactus are more universal. Lorraine Eiler shared one with me in which a young woman loved to play too much: she abandoned her still-nursing baby to play toka, a sport that is similar to field hockey. “After a period of time, the little boy got lonesome,” she said, summarizing the narrative. “And he walked off and sat down, and up sprung a Ha:sañ.” Terrol Johnson told a similar story. He learned his respect for the saguaro early, he told me: he was a typical rambunctious kid, tossing rocks and sticks at the tall sentinels, when his grandmother ran out to admonish him. “Don’t do that,” she said. “They’re people.” Then came the spanking, Johnson said, laughing. That ensured he would not forget who the saguaro was.

The national environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which has been called the “Magna Carta” of environmental law, requires the federal government to conduct in-depth environmental studies before embarking on any kind of construction project. In 2008, when a five-mile stretch of border wall was planned near Lukeville, Arizona, the resulting report ran nearly two hundred pages. No such analysis was conducted for the wall in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, because in 2019, with the stroke of a pen, Kevin McAleneen, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, defanged the Endangered Species Act, along with forty other laws.

McAleneen was granted this power by the Real ID Act, which, when passed in 2005, was advertised as an effort to keep US driver’s licenses out of the hands of terrorists. The bulk of the law focused on a rigorous new application process, an idea that drew objections from both parties in part because it would overburden local DMV offices. Nonetheless, the act was attached to what The New York Times called a “must-pass” spending package, supporting troops in Iraq. Given the timeline of its addition to the package, the text avoided the standard scrutiny of committees and hearings. An overlooked loophole allowed the DHS secretary to waive federal laws to expedite construction of border barriers. As a result, the border has become a “lawless vacuum,” in the words of Brian Segee, a legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity. The center’s lawsuits, aiming to stop wall construction, have all been dismissed.

Even beyond the border zone, our current suite of environmental laws is showing its limits. Today’s protections come mostly through permitting processes: NEPA, for example, does not forbid environmentally harmful projects; it simply requires that the federal government apply for certain permits and hold certain meetings before it begins to build. Thomas Linzey, an environmental lawyer and the senior legal counsel at the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights, noticed early in his career that his job mostly consisted of pointing out problems with the permits. Winning, then, was losing: the builders emerged from the trial with clear directions on how to fix the permit, and then simply reapplied. There was almost no way for a community to forbid an encroaching project.

Transformative legal victories don’t come from creating agencies and regulations, Linzey says. “The abolitionists didn’t ask for a slave protection agency, did they?” as he once put it in a speech. The abolitionists were fighting against the idea that people could be considered property, and the answer was to secure those people’s rights. Today, Linzey points out, nature is considered property. Perhaps it’s time that nature, too, be given rights.

Nonhuman entities have long been involved in lawsuits. In 1403, for example, a pig was put on trial in France for murder. In 1545, wine growers in Saint-Julien sued weevils for attacking their vines. In 1659, an Italian politician sued the region’s caterpillars, which, per the complaint, had engaged in trespass as they gorged on local gardens. Note that these lawsuits targeted animals. The idea that some nonhuman entity might do the suing is much more recent. In 1971, in the closing minutes of a lecture on property law at the University of Southern California, professor Christopher Stone noticed his students’ interest was waning. So, to regain their attention, he improvised a provocative question: what would happen if nature—rivers and lakes, trees and animals—were granted legal rights?

The gambit worked. The students proved enthusiastic, and Stone decided to seek a case in which he might test the idea. In the case he found, Sierra Club v. Morton, an environmental nonprofit was hoping to stop the development of a California valley into a ski resort. The Supreme Court was considering whether or not the Sierra Club had standing, which, under current law, required that they be able to show they’d suffer irreparable harm due to the development. By the time Stone uncovered the case, oral arguments were just months away. So Stone cranked out an essay to be as published in the next edition of the Southern California Law Review, which he knew would be read before publication by Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who was serving as the issue’s guest editor.

Stone pointed out in the essay that the legal world is already filled with “inanimate rights-holders: trusts, corporations, joint ventures, municipalities, Subchapter R partnerships, and nation-states, to mention just a few. Ships, still referred to by courts in the feminine gender, have long had an independent legal life.” So why not lakes and rivers, rocks and trees and animals? Or, in this case, a mountain? Children and other “legally incompetent” humans are represented in court by guardians; if the mountain was granted legal standing—the ability to file suit, in other words—a group like the Sierra Club could be named guardian instead of having to prove that the group itself was harmed.

Douglas, a noted environmentalist, wound up invoking Stone’s ideas in a dissenting opinion. Ecological communities are living things, he argues, and therefore their voice “should not be stilled.” The people best positioned to give voice to the voiceless, he figured, were “those people who have so frequented the place as to know its values and wonders.” This opinion did not ultimately set any precedent for the “rights of nature,” as the concept has come to be known, but it proved that this idea could be taken seriously even in the nation’s highest court.

After being cited by Douglas, the idea mostly lay dormant for decades. Then, in 2006, a city councillor in Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, approached Thomas Linzey seeking help to stop the nearby dumping of toxic waste. Linzey picked up Stone’s old idea. He helped draft a city resolution that granted “natural communities and ecosystems” status as legal “persons,” which became the first known rights-of-nature law in the world.

There are dozens now, in at least ten US states, according to the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights. Some have been struck down in court for their vagueness, or for contradicting existing legislation. (The law in Tamaqua has been credited for deterring further industrial development in the town but has never been tested in court.) The long-term prospects for the idea in the United States may soon be clarified: Last April, five waterways in Florida became the first natural entities to sue in US court to enforce their legal rights. This string of lakes had been granted legal personhood through an amendment that Linzey helped draft and that voters overwhelmingly approved in November 2020. The case may depend on how the judge evaluates a state law, passed a few months before the referendum, that forbids any local government from establishing rights-of-nature laws.

“Instead of being reactive, we must lay down our law—that we have understandings about how we relate to our home place, the place where the Creator put us. It’s important for the Indigenous people to make these declarations and make them publicly.”

Various groups—agricultural groups, especially—have suggested that the rights-of-nature concept is a threat to the tenets of personal property. But rights evolve over time, as Stone pointed out in his essay. “Each time there is a movement to confer rights onto some new ‘entity,’ the proposal is bound to sound odd or frightening or laughable,” he wrote, noting that women and Black people, among other groups, were long denied rights—declared, in essence, less than people. Until something or someone receives its formally granted rights, many will struggle to “see it as anything but a thing for the use of ‘us’—those who are holding rights at the time,” Stone wrote.

In an Indigenous context, the idea that nature has rights is not odd at all. Ak-chin farming and the nawait ceremony link the fruits of a wild-growing cactus to the harvest of domesticated species; such linkages are typical of many Indigenous cultures, whose stories reveal a world filled with entities—human and “more than human”—that have personal, reciprocal relationships, rather than a cosmology that suggests humans are somehow separate from other beings. Such cosmologies imply an expansive idea of citizenship, a broader sense of community—an idea that in an era of climate change is being increasingly embraced by non-Indigenous thinkers.

This is not to suggest that the rights-of-nature concept is supported by every Indigenous thinker. The idea raises thorny spiritual and cultural questions, to say nothing of legal complications. Andrea Carmen, the executive director of the International Indian Treaty Council (and a member of the Yaqui Nation), noted on a recent conference call with environmental reporters that there are important questions about what parts of nature have standing, and who might serve as nature’s legal guardian in court: could, say, Monsanto one day sue on behalf of the rights of its genetically modified seeds? Carmen also indicated that some Indigenous stories describe human beings as being created after plants and animals. Legal personhood, then, becomes a demotion, an attempt to squeeze the powers of nature into a flimsy human construct.

Still, Indigenous leadership has been key in many rights-of-nature breakthroughs. Several US tribes (the Ponca of Oklahoma, Yurok, and Menominee) have passed rights-of-nature laws, including a 2018 resolution in which the White Earth Band of Ojibwe granted legal personhood to manoomin, or wild rice, a sacred food. Last August, manoomin sued Minnesota’s department of natural resources, objecting to the construction of an oil pipeline—the first rights-of-nature case filed in tribal court. The greatest successes have happened abroad, most notably a provision in the 2008 Ecuador Constitution that granted rights to nature broadly, invoking the Indigenous Andean concept of “Pachamama.” Late last year, Ecuador’s highest court ruled that the provision forbids mining and other extractive activities in a protected forest ecosystem. It is a decision that advocates hope will popularize the rights-of-nature concept not just locally, but across the world.

In 2020, as contractors were bulldozing cacti and sucking up groundwater along Arizona’s southern border, ethnobotanist Gary Nabhan co-convened an intertribal/interfaith group, called the “Healing the Border Project.” Nabhan, an Ecumenical Franciscan brother, completed a PhD in interdisciplinary arid lands resource sciences at the University of Arizona in 1983, focusing on O’odham agriculture. In the years since, he has worked alongside Indigenous farmers and foragers on both sides of the border and published well-regarded books about the region. This new coalition aims to protect sacred sites in the path of the wall; their tactics include community organizing and legal strategies. (The Kalliopeia Foundation, which funds this magazine, has also supported the project’s work.)

The group has helped to establish the sacred status of Quitobaquito Springs in case law. A Hia-Ced woman named Amber Ortega was arrested last fall while protesting at the wall near the springs. In January, a judge found that Ortega was not guilty of the two misdemeanor charges—interfering with an agency function and violating a closure order—because, as the judge put it, by building the wall, government had imposed “substantial burden” on her religious freedom. Lorraine Eiler, who is a member of the coalition, served as a witness in the trial.

Mona Polacca, another member of the coalition, is a longtime participant in the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Peoples Issues. Through that work, Polacca, a member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, became familiar with the rights-of-nature movement. At an early Healing the Border retreat, she raised to her colleagues its possibility as a legal strategy. “One thing I told them was that tribes—or our Indigenous people—must become proactive instead of reactive,” she told me. “Instead of being reactive, we must lay down our law—that we have understandings about how we relate to our home place, the place where the Creator put us. It’s important for the Indigenous people to make these declarations and make them publicly.”

The idea appealed to the coalition, and two of its members—Nabhan and Austin Nuñez, the chairman of one of the Tohono O’odham Nation’s eleven districts—drafted a resolution that acknowledged the legal personhood of the saguaro cactus. The resolution unanimously passed in Nuñez’s district in late January 2021. Other districts followed suit, and in May, the national legislative council gave its unanimous approval.

The resolution references the cactus’s personhood in its preamble, which notes the traditional story of a boy who became the first saguaro and highlights that O’odham spiritual traditions have long forbidden their destruction. Such traditions, the resolution states, amount to a longstanding recognition of personhood. Based on these facts, as well as a few other pieces of evidence, the resolution concludes that the tribe’s First Amendment right to religious freedom has been violated in the construction of the border wall and calls for government-to-government consultation between the tribe and the United States. The resolution, though, does not explicitly confer formal rights upon the saguaro; unlike manoomin in Minnesota, the cactus does not have standing to sue.

Nuñez told me that when he worked with Nabhan to draft the language, he considered being more direct and granting such standing. “Personally, not being a lawyer, I was thinking, well, let’s put at least our intention in there,” Nuñez said. But the saguaro that have been uprooted for the construction of the border wall lie outside the reservation’s borders; Nuñez says his district’s legal counsel worried that such a resolution might not hold up in court.2 Other members of the Healing the Border team opted for the current text, believing this version would be easier to pass—a first step, intended to raise awareness, a gesture towards a future solution, a way to translate longstanding Tohono O’odham insights into modern US law.

The idea of writing a cactus’s rights into law may seem odd within the context of our particularly American concept of freedom. The US legal system has been built mostly to protect what philosophers call “negative” freedom. It focuses on removing constraints on our human freedoms, on ensuring that no one can tell us what to do. David Grundman, the Phoenix man who was crushed to death by a falling saguaro, offers a perfect emblem: a man in a desert, shotgun blazing. This is a what’s-mine-is-mine freedom, an ability to lay claim and lay waste, to clear-cut the vegetation, to pump the water, to strip-mine the copper, without a care for what happens on the other side of your property line—a freedom ironically dependent on the construction of fences and walls.

The Indigenous concept of community, meanwhile—of reciprocal relationships between its members, whether human or nonhuman—suggests a “positive” conception of liberty: freedom as the capability to flourish, as the power to become whatever you’re meant to be. But this can be accomplished only if we all work together—if every member of the community receives support and respect and aid.

Desert life offers a reminder that we humans, too, need aid. Even the Border Patrol has found that we ignore nature at our peril, as Mona Polacca points out. Last year, a particularly strong monsoon ripped through many gates in the wall, taking a first step towards the dismantling that the Healing the Border coalition seeks. “We didn’t do any of that work,” Polacca said. “The laws of nature did.” The monsoons will only grow worse as the climate changes. So too will floods and wildfires, droughts and heatwaves. This Earth is looking increasingly precarious. To grant the saguaro its freedom need not be an act of selflessness, then. How we fare in the coming years seems to increasingly depend on how willing we are to collaborate—with one another, and with the world’s many other beings. Now, then, may be the time to bring our own laws in line with nature’s.

- From Jane H. Hill and Ofelia Zepeda, “Tohono O’odham (Papago) Plurals” Anthropological Linguistics 40, no. 1 (Spring 1998): 1-42.

- Similar concerns led tribal judges from the White Earth Nation to dismiss the manoomin case in early March, as this story was undergoing final edits; the pipeline in question passes through off-reservation territory. Frank Bibeau, White Earth’s attorney, says they plan to file a motion to reconsider, citing new revelations about the damage caused by pipeline construction.

Rights of Nature at the Border

As the border wall and climate change disrupt the ecological balance at Quitobaquito Springs, an oasis in the Sonoran Desert that serves as one of the most sacred sites for the Hia-Ced O’odham people, Lorraine Eiler speaks on behalf of the more-than-human beings who inhabit this place and deserve to live with integrity.